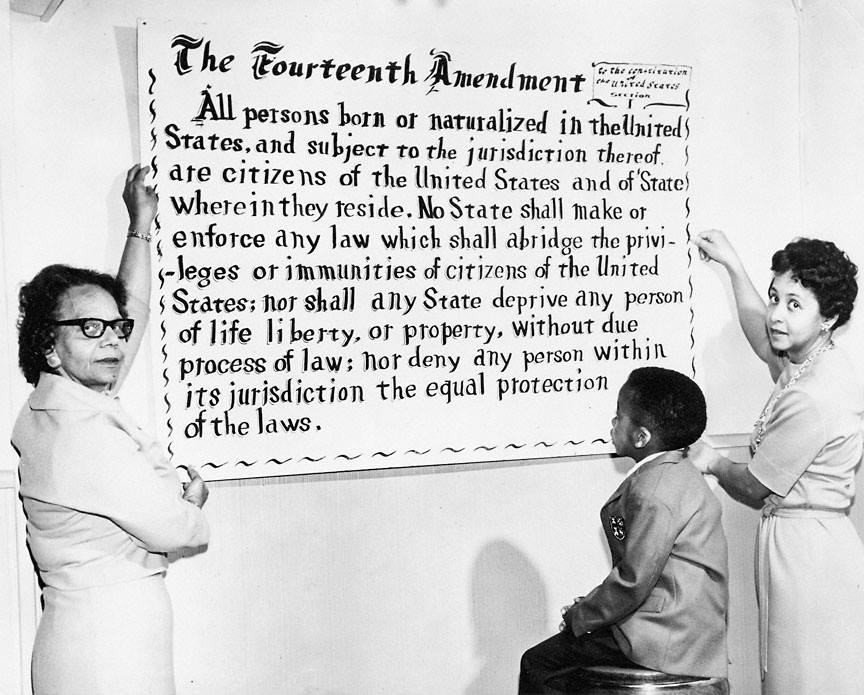

On June 13, 1866, the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was passed. This Amendment, known as the one of the three Reconstruction Amendments, granted citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States.” The 14th Amendment forbid states to deny any person “life, liberty, or property, without due process of law” or to deny any person “equal protection of the laws.” The amendment was adopted on July 9, 1868. See a full copy of 14th Amendment at the National Archives.

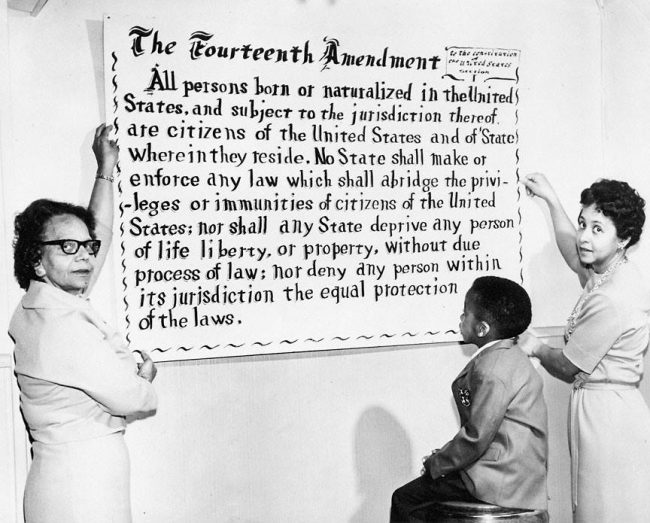

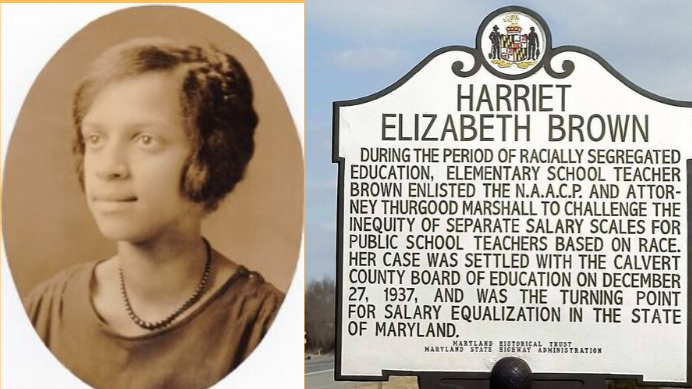

Sylvia N. Thompson (left) with her daughter Addie Jean Haynes and Addie’s ten-year-old son Bryan Haynes holding up a poster-sized copy of the 14th Amendment at the NAACP Portland office in 1964.

The 14th Amendment was designed to grant citizenship to and protect the civil liberties of people recently freed from slavery. As historian Martha Jones explains on Democracy Now,

And so, in 1868, after Congress has promulgated a 14th Amendment, the states will ratify it, and for the first time the U.S. Constitution will provide that all persons born in the United States are citizens of the United States. It is a remedy, a radical remedy, to bring millions of former slaves into the body politic, but it is written in a way that gives it a lasting and enduring effect, which is to make every person, regardless of race, and, I might say, regardless of religion, regardless of descent, regardless of political affiliations, make every person born in the United States a citizen of the United States.

However, as described in the examples below, there were soon to be limitations on those protections.

When federal charges were brought against several white supremacists responsible for the Colfax Massacre against African Americans, the Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Cruikshank that the 14th Amendment only applied to state actions and offered no protections against acts by individual citizens.

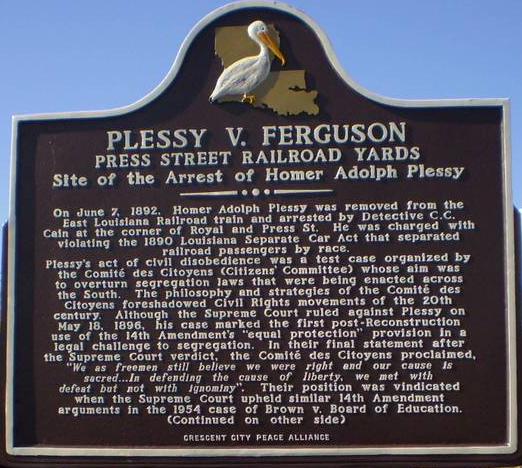

These liberties were undermined and limited after the Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) Supreme Court case which upheld the constitutionality of segregation and Jim Crow laws and Black codes.

Howard Zinn writes in Chapter 11: Robber Barons and Rebels of A People’s History of the United States:

Very soon after the Fourteenth Amendment became law, the Supreme Court began to demolish it as a protection for Black [people], and to develop it as a protection for corporations. However, in 1877, a Supreme Court decision (Munn v. Illinois) approved state laws regulating the prices charged to farmers for the use of grain elevators. The grain elevator company argued it was a person being deprived of property, thus violating the Fourteenth Amendment’s declaration “nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law.” The Supreme Court disagreed, saying that grain elevators were not simply private property but were invested with “a public interest” and so could be regulated. . . .

By this time [1886, the year in which the Supreme Court had removed 230 state laws which sought to regulate corporations], the Supreme Court had accepted the argument that corporations were “persons” and their money was property protected by the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Supposedly, the Amendment had been passed to protect Negro rights, but of the Fourteenth Amendment cases brought before the Supreme Court between 1890 and 1910, nineteen dealt with the Negro, 288 dealt with corporations. [Read more in A People’s History of the United States.]

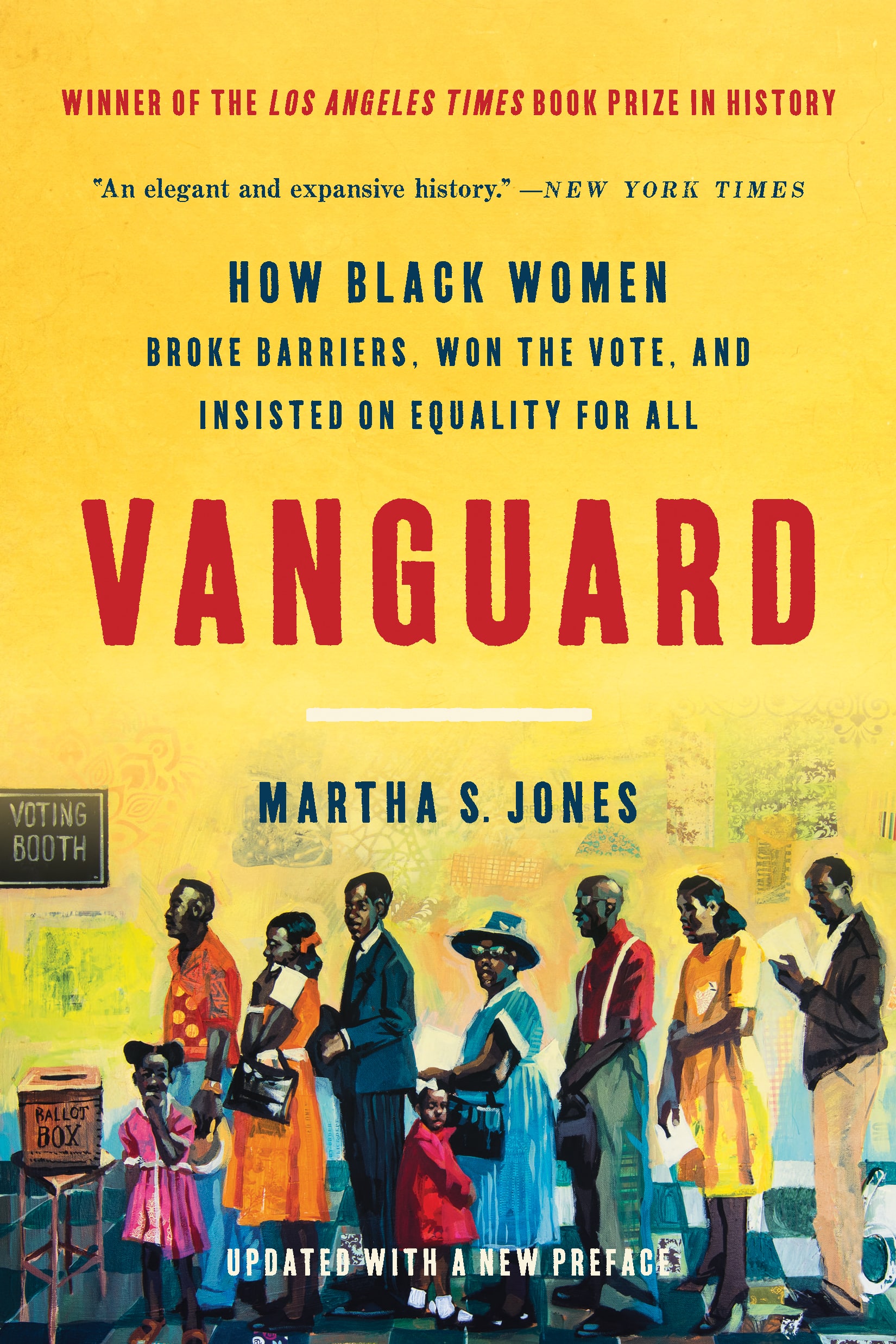

Learn about issues of citizenship today and before the 14th Amendment from an interview with Martha S. Jones, author of Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America in a Democracy Now! interview, How African Americans Fought For & Won Birthright Citizenship 150 Years Before Trump Tried to End It.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn