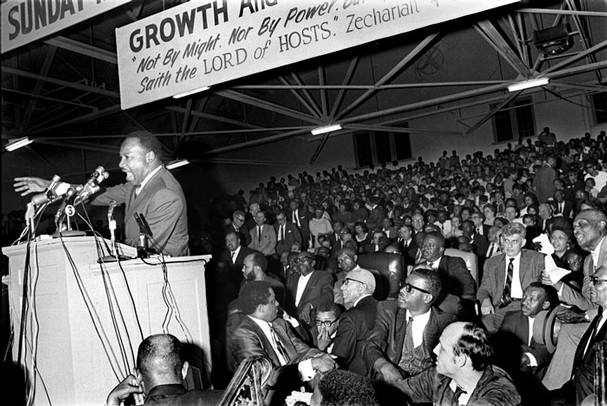

Source: Frisc/Pamela Gentile

By Hajar Yazdiha

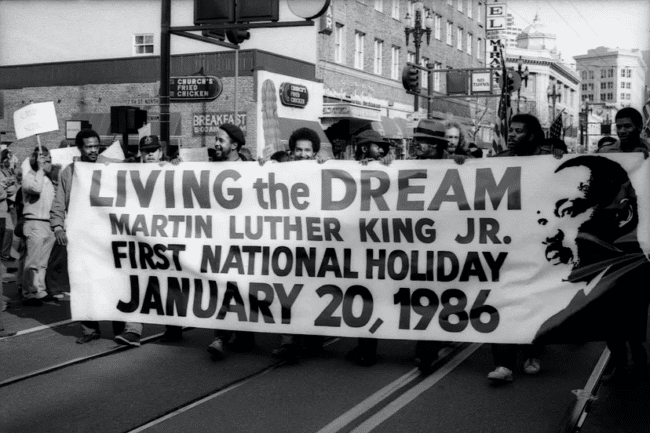

On Monday, January 20, 1986, the United States celebrated its first national Martin Luther King Jr. holiday. It was three years after the holiday was signed into law and 18 years after the fight for a King holiday began.

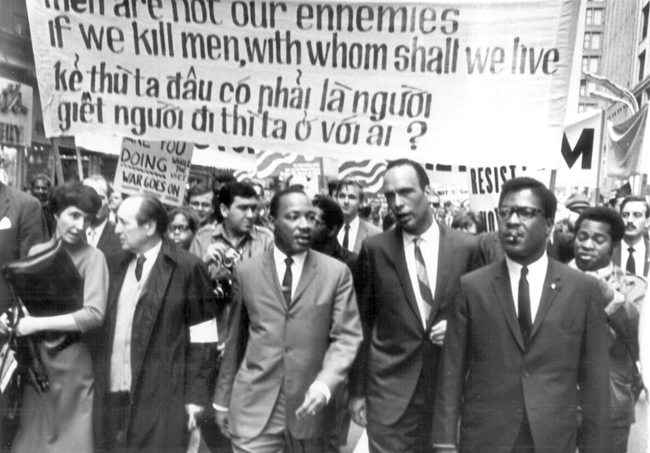

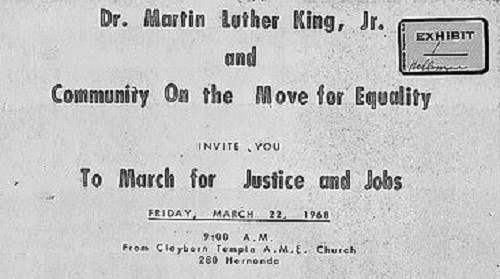

On April 8, 1968, four days after Dr. King was assassinated, Congressman John Conyers introduced legislation to commemorate King with a national holiday. At the time of King’s assassination, he was an unpopular figure among the majority of the white public, having spoken out against the Vietnam War and the evils of capitalism.

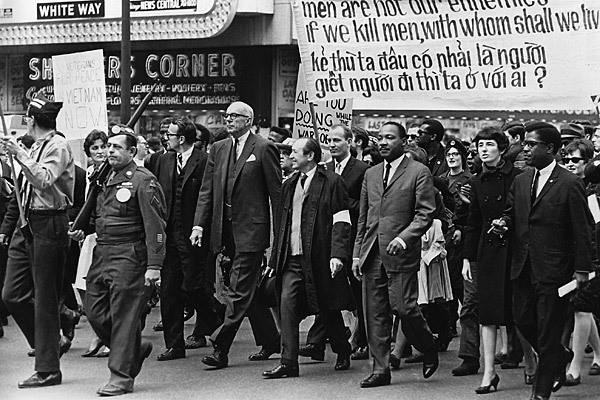

King knew there were risks in speaking out not only against racism but also U.S. militarism and economic inequality. President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration warned him to stay out of these waters. Speaking out against the government during a time of war would threaten his close relationship with the president who had signed the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Yet King was not alone among civil rights activists in opposing the war — in fact, his wife Coretta Scott King and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had already spoken out.

King knew there were risks in speaking out not only against racism but also U.S. militarism and economic inequality. President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration warned him to stay out of these waters. Speaking out against the government during a time of war would threaten his close relationship with the president who had signed the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Yet King was not alone among civil rights activists in opposing the war — in fact, his wife Coretta Scott King and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had already spoken out.

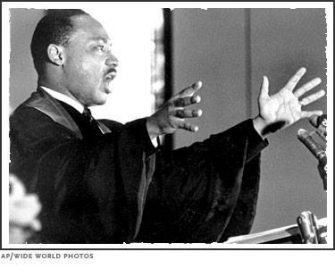

Still, some advisors pushed King to stay in his lane and focus on the long battle ahead for civil rights at home. Yet the images of Vietnamese children burning in U.S.-funded napalm compelled King to break the silence. With the aid of a trusted circle who supported the anti-war stance, including advisor and Spelman professor Vincent Harding, King wrote his lifechanging speech, “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence.”

After speaking out against the war, King lost mass support, political alliances including the allyship of President Lyndon B. Johnson, and 168 newspapers publicly denounced him. His public approval rating that year was just 25 percent. King was challenging the deepest structures of a society built on settler colonialism, chattel slavery, and white supremacy. King’s critiques would require a radical redistribution of resources and power in U.S. society, ideas that many white people found threatening — conservative and liberal alike.

After his assassination, the King holiday had few backers. Two months later, Coretta, now a widow in addition to being an outspoken civil rights and anti-war activist, founded the King Center in Atlanta as “the official, living memorial dedicated to the advancement of the legacy.” The Center became a powerful organizing force for the King holiday.

For fifteen years, the King family led by Coretta, Black congressional members like John Conyers and Shirley Chisholm, and the Congressional Black Caucus led a movement to establish the federal King holiday. White conservative political leaders — the same forces that so staunchly opposed civil rights in King’s day — like Congressman Gene Taylor (R-Missouri), Senator Jesse Helms (R-North Carolina), and congressman John Ashbrook (R-Ohio) continually fought back.

Source: Frisc/Pamela Gentile

The conservative coalition unearthed every conspiracy and criticism lobbed at King during his life to throw doubt around King’s legacy and ensure the federal holiday would not pass. They said King was too divisive, that he had Communist ties, had questionable morals, was a reverse racist against white people, and that he provoked violence. To commemorate King would be to raise the Black civil rights leader to the level of reverence long reserved for white men like Abraham Lincoln and George Washington. They were not only resisting the commemoration of King, they were resisting the recognition of multicultural democracy.

The holiday would not even come up for a vote until 1979, and then it would fall five votes short. Yet Coretta Scott King and the movement for the King holiday would not yield, and it was growing.

In 1980, the popular musician Stevie Wonder released a song called “Happy Birthday.” Behind the cheery harmony, the song was a political call to commemorate Dr. King. Wonder sang, “Just because some cannot see / The dream as clear as he,” in due time we would come to know the heroic King.

By the end of President Reagan’s first term, the political pressure had mounted, the congressional votes were in place, and Reagan — a long time critic of Dr. King and opponent of the Civil Rights Movement — knew he would have to sign the holiday into law. On November 2, 1983, President Reagan signed the King Holiday Bill into law as a federal holiday to be held annually on the third Monday of January near King’s January 15 birthday.

Source: Frisc/Pamela Gentile

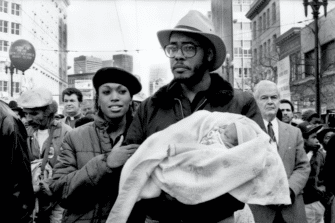

Three years later on January 20, 1986, the King holiday would be celebrated for the first time. From marches to teach-ins to a freedom train, many people celebrated King’s legacy. Other white conservatives maintained their hostility toward King and his commemoration, as in Buffalo, New York, where a long-controversial statue of Dr. King was painted white.

Notably, in 1986, only 17 states had adopted the King holiday. The battle for individual states to adopt the holiday and commemorate the civil rights leader would continue into the next century. South Carolina was one of the last states to adopt the King holiday in the year 2000.

Hajar Yazdiha is assistant professor of sociology at the University of Southern California, faculty affiliate of the USC Equity Research Institute, and a CIFAR Azrieli Global Scholar (2023–2025). She is the author of The Struggle for the People’s King: How Politics Transforms the Memory of the Civil Rights Movement.

Hajar Yazdiha is assistant professor of sociology at the University of Southern California, faculty affiliate of the USC Equity Research Institute, and a CIFAR Azrieli Global Scholar (2023–2025). She is the author of The Struggle for the People’s King: How Politics Transforms the Memory of the Civil Rights Movement.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn