The 1872 National Convention of Colored Citizens, held during Reconstruction in New Orleans, La. Source: Library of Congress

After the Cincinnati riots of 1829, Hezekiel Grice decided to take action and organize for change. The free, Black sixteen-year-old from Baltimore built on previous Black organizing networks to launch a national, representative gathering of Black communities across the United States.

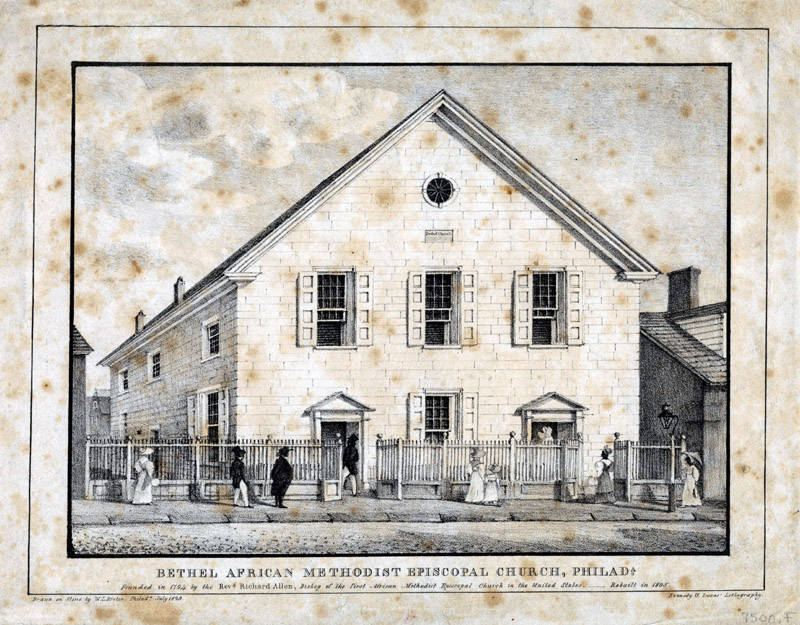

In response to Grice’s outreach and encouraged by vocal support from Bishop Richard Allen, who was Senior Bishop for the African Methodist Episcopal Churches, Black organizations in nine states elected 40 men to represent them at meetings that would address Black concerns.

The first 40 representatives met in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in September 1830 at Bethel Church. They met for five days of closed session meetings, from Sept. 15–20, before they opened for public meetings Sept. 20–24. Rev. Allen presided over the meetings as President. During this time, they produced a Constitution and addressed the organizations that sent them.

This series of formal meetings and proceedings launched the Colored Conventions Movement, also called the National Negro Convention Movement. Here’s a link to an exhibit about that first meeting, The Meeting That Launched a Movement: The First National Convention.

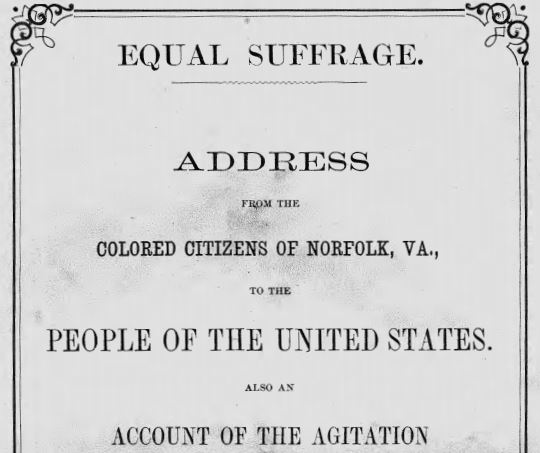

In the Colored Conventions Movement’s Constitution, published that year, Rev. Allen addressed the “Free People of Colour of these United States.” He began his address by invoking the philosophical groundings of the United States’ own Constitution. He wrote,

Impressed with a firm and settled conviction, and more especially being taught by that inestimable and invaluable instrument, namely, the Declaration of Independence, that all men are born free and equal, and consequently are endowed with unalienable rights, among which are the enjoyments of life, liberty, and the pursuits of happiness.

Viewing these as incontrovertible facts, we have been led to the following conclusions; that our forlorn and deplorable situation earnestly and loudly demand of us to devise and pursue all legal means for the speedy elevation of ourselves and brethren to the scale and standing of men.

After describing the organization’s goals and strategy for improving conditions for Black people in North America, Rev. Allen asked for the public’s support:

To effect these great objects, we would earnestly request our brethren throughout the United States, to co-operate with us, by forming societies auxiliary to the Parent Institution, about being established in the city of Philadelphia, under the patronage of the GENERAL CONVENTION.

Mary Ann Shadd Cary was one of the few Black women elected to serve as a delegate. She attended the national convention in 1855. Source: National Women’s Hall of Fame

The organization remained active through the end of the 19th Century, evolving as the United States transformed from a slave society to a free society under Reconstruction to an oppressive society under Jim Crow. From the Colored Conventions Project website:

From 1830 until the 1890s, already free and once-captive Black people came together in state and national political meetings called “Colored Conventions.” Before the War, they strategized about how to achieve educational, labor and legal justice at a moment when Black rights were constricting nationally and locally. After the War, their numbers swelled as they continued to mobilize to ensure that Black citizenship rights and safety, Black labor rights and land, Black education and institutions would be protected under the law.

The Colored Conventions movement took place during critical decades which witnessed devastating anti-Black race riots and the growing popularity of the American Colonization Society; the Fugitive Slave Law and the proliferation of derogatory representations of Blacks; the Civil War and Reconstruction; and the return of Black disenfranchisement in legal, labor, and educational spheres in the late nineteenth century.

The Colored Conventions Project seeks to collect and make available the vast but rare documentation from the 19th century Movement for education. On top of archiving and publishing about the lives of male delegates, the Project also accounts for the crucial work done by Black women in the broader social networks that made these conventions possible. It endeavors to transform teaching and learning about this historic organizing effort by bringing it to digital life for a new generation of students.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn