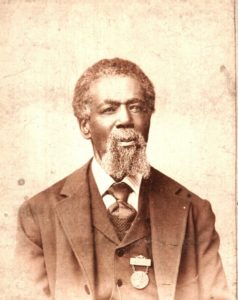

Thomas Mundy Peterson wearing the medallion he was awarded by the citizens of Perth Amboy. Click for more info from NMAAHC. Source: Public domain

On March 30, 1870, the 15th Amendment to the United States Constitution was formally adopted. It had been ratified on February 3, 1870 as the third and last of the Reconstruction Amendments. On March 30, Secretary of State Hamilton Fish proclaimed the 15th Amendment to be officially part of the U.S. Constitution. Historian Stephen West explains, “That was considered necessary because of questions about its status amidst the messy and irregular politics of Reconstruction.”

The 15th Amendment is described in Freedom’s Unfinished Revolution,

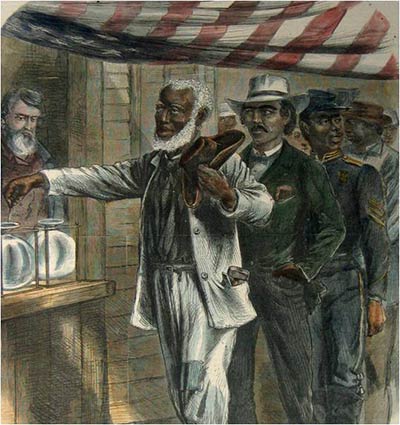

In 1870, two years after the 14th Amendment was ratified, Congress and the states responded to another round of racial violence in the South by providing additional constitutional protection for the Black electorate. The 15th Amendment declared that the right of U.S. citizens to vote could “not be abridged or denied” by any state” on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

The 14th and 15th Amendments — sporadically enforced until 1876 (the end of Reconstruction), then rarely enforced until 1954 (the Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation decision by the Supreme Court) — provided the legal foundation for the civil rights movement of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. They are part of the enduring constitutional legacy of Reconstruction.

On March 31, Thomas Mundy Peterson became the first African-American to participate in an election in a state where African Americans had not been allowed to vote before the 15th Amendment. He participated in a local election in Perth Amboy, New Jersey. He later held political office and sat on a jury.

Decades later, the school where Peterson had worked as a custodian was renamed after him. This is just one of many stories from the Reconstruction Era that are missing from most textbooks. Note that,

On a per capita and absolute basis, more African Americans were elected to public office during the period from 1865 to 1880 than at any other time in U.S. history. These legislatures brought in programs of public benefit such as universal public education.

Over time, the amendment would be narrowly interpreted, allowing states to implement restrictions such as poll taxes and literacy tests that did not mention race by name, but effectively prevented most African Americans from voting.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn