On December 25, 1521, the enslaved people on a Santo Domingo sugar plantation owned by the son of Christopher Columbus attempted to free themselves and take over the land. This was the earliest recorded slave uprising in the Americas.

The revolt was violently put down by Spanish colonizers and, 11 days later, the governor issued a new set of repressive laws regulating “Blacks and slaves,” designed to prevent future rebellions. In The Santo Domingo Slave Revolt of 1521 and the Slave Laws of 1522: Black Slavery and Black Resistance in the Early Colonial Americas, Anthony Stevens Acevedo writes:

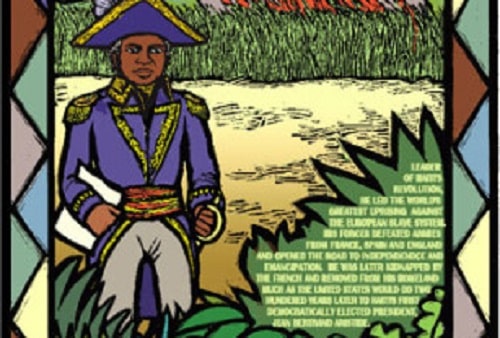

An account of enslaved people’s revolts, 1600s–1800s. Source: Library of Congress

The life and death confrontation between the Spanish cavalry and the Black rebels did not last long. Equipped with superior weapons, the Spaniards crushed the Black rebels who had managed to arm themselves with objects that they had converted into impromptu weapons as they waited and planned the right moment to launch the attack and break free. The death of the rebels strengthened the reign of a social order in La Española based on inequality, on the accumulation of wealth in the hands of a few at the expense of the majority. That social order still remains in place today.

Nevertheless, the uprising established a precedent in the minds of everyone. To keep the system in place, Spanish colonial authorities acted quickly and about ten days later, in 1522, they sanctioned a tough set of laws specifically devoted to limiting the rights of Black peoples in La Española, whether enslaved or not. These were punitive laws whose goals were to control and prevent similar insurrections from ever happening again.

The 1522 laws are the oldest surviving set of Spanish legislation issued to regulate and punish Black peoples who violated the social norms in La Española. The laws also imposed punishments to those who helped enslaved Blacks to escape, whether Whites or otherwise. The ideological component of the slavery society was put into practice in La Española to control (to varying degrees) everyone everywhere. Equally significant is the fact that the 1522 laws preceded for a long time all subsequent “Black codes” destined at subjecting the generations of millions of Black men and women that would be held in bondage throughout history in the entire continent, including the United States. Read more.

BlackPast describes the Santo Domingo rebellion’s legacy:

Although the rebellion failed, memory of it encouraged future rebellions, which represented an ongoing challenge to Spanish rule in the Caribbean until slavery was abolished in the nineteenth century. Read more.

This event is included on the Zinn Education Project’s Climate Crisis Timeline.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn