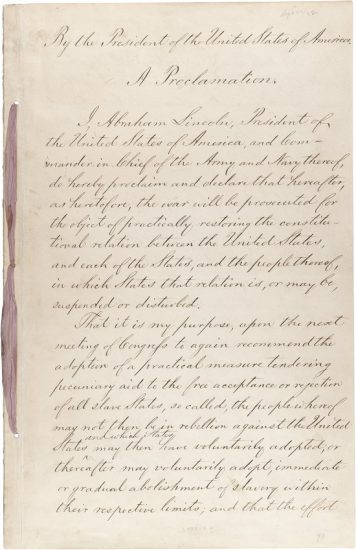

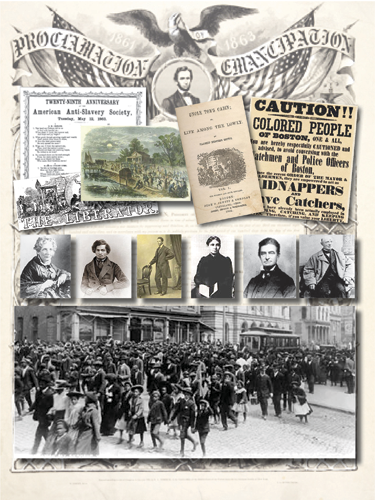

On Sept. 22, 1862, Abraham Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

On Sept. 22, 1862, Abraham Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

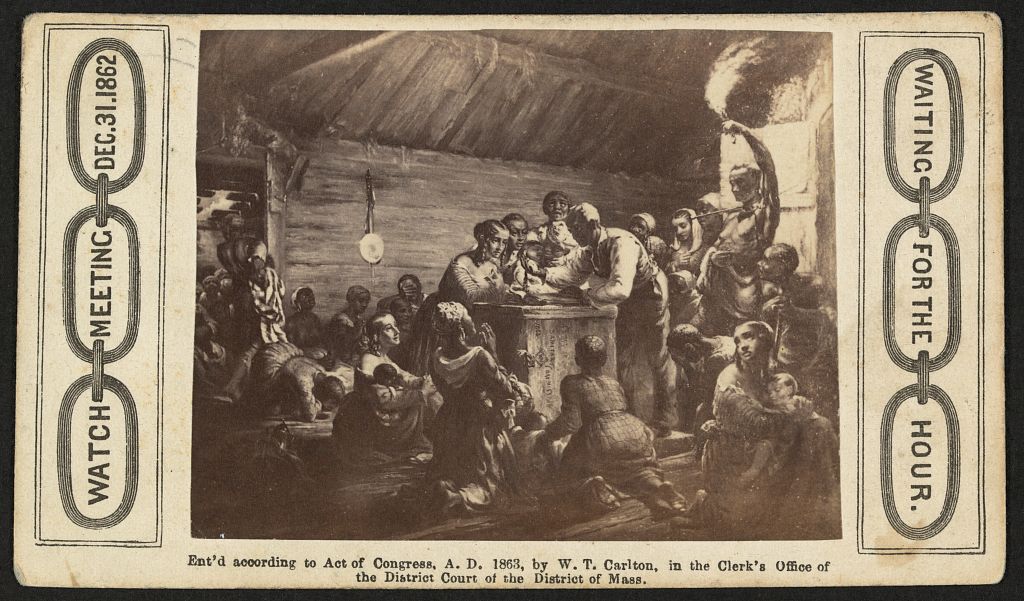

It said that on Jan. 1, 1863, “. . . all persons held as slaves within any State, or any designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever, free.”

The Emancipation Proclamation applied only to the 10 states that were still in rebellion.

Bill Bigelow notes in a lesson called “A War to Free the Slaves?”:

Few documents in U.S. history share the hallowed reputation of the Emancipation Proclamation. Many, perhaps most, of my students have heard of it. They know — at least vaguely — that it pronounced freedom for enslaved African Americans, and earned President Abraham Lincoln the title of Great Emancipator.

This lesson asks students to think about what these documents reveal about Lincoln’s war aims. Was it a war to free the slaves? Lincoln never said it was. Most textbooks don’t even say it was. And yet the myth persists: It was the war to free the slaves.

This lesson’s intent is important but narrow. Although Lincoln did not begin his presidency with the intent to abolish slavery, that doesn’t mean that the Confederacy did not secede with the intent to maintain slavery. And, of course, the seceding states did believe that it was Lincoln’s intention to end slavery. As South Carolina delegates wrote in their “Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union,” “A geographical line has been drawn across the Union, and all the States north of that line have united in the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States, whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery.”

This lesson introduces students to documents that puncture the myth that Lincoln waged the war to “free the slaves.” It concludes by asking them to reflect on why Lincoln and the Republicans would wage war, if it was not to end slavery.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn