Elizabeth Jennings Graham, ca. 1895.

On July 16, 1854, schoolteacher Elizabeth Jennings Graham successfully challenged racist streetcar policies in New York City. Her case went to court and was publicized by Frederick Douglass.

Here is a description excerpted from 50 American Revolutions You’re Not Supposed to Know: Reclaiming American Patriotism.

On July 16, 1854, Elizabeth “Lizzie” Jennings, a 24-year-old schoolteacher setting out to fulfill her duties as organist at the First Colored Congregational Church on Sixth Street and Second Avenue, fatefully waited for the bus on the corner of Pearl and Chatham. Getting around 1854 New York City often involved paying a fare to board a large horse-drawn carriage, the forerunner to today’s behemoth motorized buses. For Black New Yorkers like Jennings, it wasn’t that simple.

Pre-Civil War Manhattan may have been home to the nation’s largest African-American population and New York’s Black residents may have paid taxes and owned property, but riding the bus with whites, well, that was a different story. Some buses bore large “Colored Persons Allowed” signs, while all other buses — those without the sign — were governed by a rather arbitrary system of passenger choice. . .

Against such a volatile backdrop, Lizzie Jennings opted for a bus without the “Colored Persons Allowed” sign. The New York Tribune described what happened next: “She got upon one of the Company’s cars on the Sabbath, to ride to church. The conductor undertook to get her off, first alleging the car was full; when that was shown to be false, he pretended the other passengers were displeased at her presence; but (when) she insisted on her rights, he took hold of her by force to expel her. She resisted.” . . .

Against such a volatile backdrop, Lizzie Jennings opted for a bus without the “Colored Persons Allowed” sign. The New York Tribune described what happened next: “She got upon one of the Company’s cars on the Sabbath, to ride to church. The conductor undertook to get her off, first alleging the car was full; when that was shown to be false, he pretended the other passengers were displeased at her presence; but (when) she insisted on her rights, he took hold of her by force to expel her. She resisted.” . . .

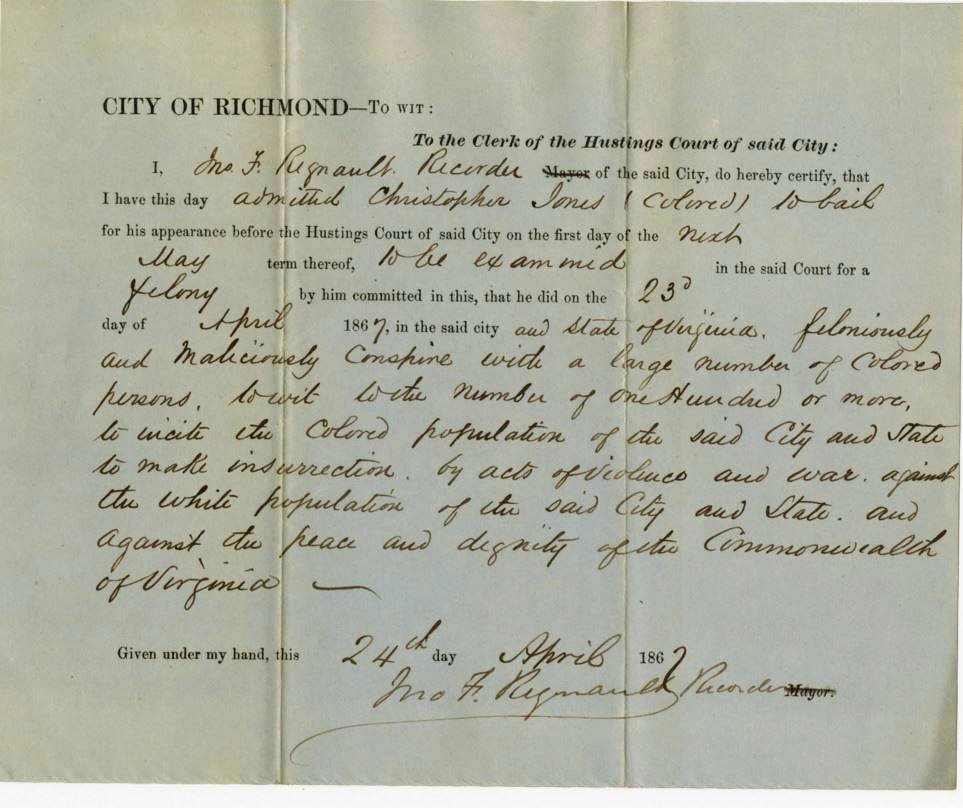

This would not be the end of it. “Jennings was well connected,” says Williams. “Her father was an important businessman and community leader with ties to the two major Black churches in the city.” Not satisfied with the massive rally that took place the following day at her church, Elizabeth Jennings hired the law firm of Culver, Parker & Arthur and took the Third Avenue Railway Company to court.

In a classic “who knew?” situation, Jennings was represented by a 24-year-old lawyer named Chester A. Arthur — yes, he who would go on to become the 21st president upon the death of James A. Garfield in 1881. The trial took place in the bus company’s home base of Brooklyn — then a separate city — where, in early 1855, Judge William Rockwell of the Brooklyn Circuit Court ruled in the Black schoolteacher’s favor.

By 1860, all of the city’s street and rail cars were desegregated.

Her life was connected to another major historic event, this time when her one-year-old son tragically died during the New York City Draft Riots.

Read More

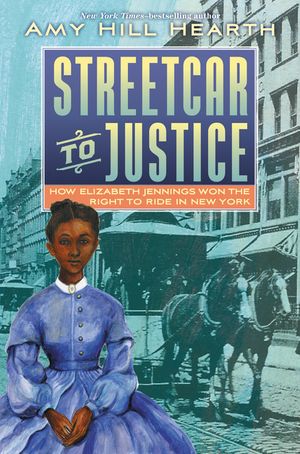

Streetcar to Justice: How Elizabeth Jennings Won the Right to Ride in New York by Amy Hill Hearth

The Schoolteacher on the Streetcar by Katharine Greider, New York Times, Nov. 13, 2005.

Narrative Network A description of the event in Jennings’ own words, read aloud at a mass meeting in New York.

Elizabeth Jennings in “Early African New York,” Columbia University.

BlackPast.org profile of Elizabeth Jennings

Stuff You Missed in History Class podcast segment on Elizabeth Jennings.

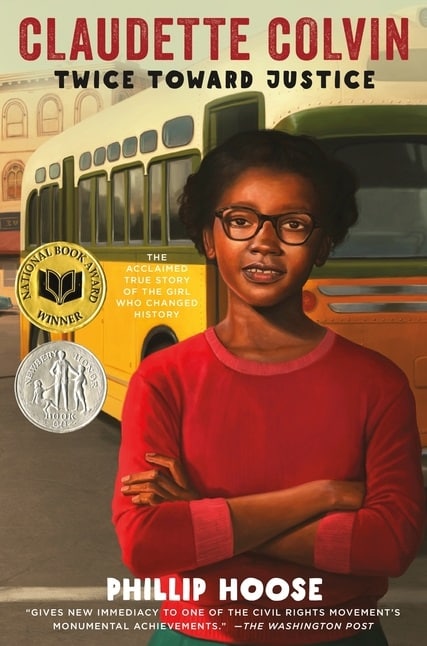

Transportation Protests: 1841 to 1992. Dozens of examples of key individuals and organizations who took a stand against segregated transit.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn