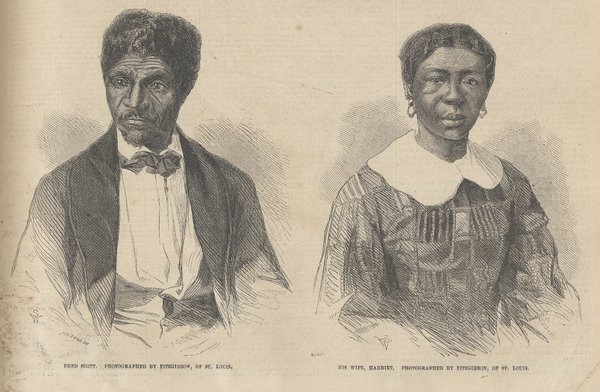

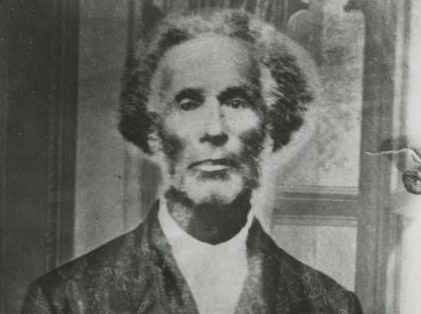

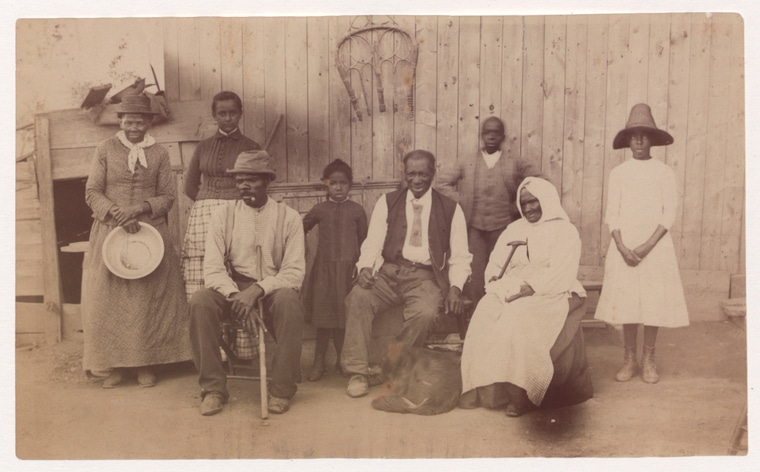

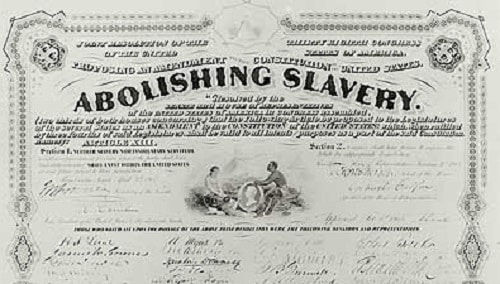

Dred and Harriet Scott. Wood engraving from photograph by Fitzgibbon, St. Louis Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, June 27, 1857. Source: Newberry Library and Chicago History Museum

On March 6, 1857 the U.S. Supreme Court declared in Dred Scott v. Sandford that:

Any person descended from Africans, whether slave or free, is not a citizen of the United States, according to the Constitution.

Martha Jones, author of Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America, provides background on the case in an interview “How African Americans Fought For & Won Birthright Citizenship 150 Years Before Trump Tried to End It” via Democracy Now!

[Dred] Scott is an enslaved man in the city of St. Louis, Missouri. His case arises because, in the company of his owner, Scott travels to free territory — among those places, Minnesota. And the claim had long been that persons who were held as slaves but resided in free soil became free themselves. Now, Scott lives in this Minnesota territory. He meets his wife Harriet. They begin to have a family. They marry. And then, finally, they return to St. Louis, where they are still held as slaves. And by the early 1850s, I think they are concerned that they might be sold, that their family might be separated. They are always at risk as enslaved people.

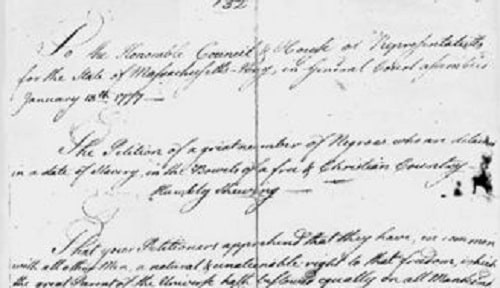

And they begin what is, as you explain, a series of freedom suits, a tireless effort to secure the freedom for themselves and for their two daughters. These cases make their way through the Missouri state courts and, when they fail there, wind up before the U.S. Supreme Court. There, Chief Justice Roger Taney, now notoriously, pens an opinion that deprives the Scott family of pursuing their freedom claims in the federal court, but, as importantly, makes sure that no African American, enslaved or free, can bring claims before these same high court venues.

This is a devastating blow, as you can imagine, to free African Americans, who have long promoted the view that they are birthright citizens. But what’s important to remember about Dred Scott is that its impact on the ground in the daily lives of African Americans is very limited. Very few courts are willing to enforce the literal terms of Dred Scott in the cases that they hear. State legislatures are not prepared to defer to the court’s reasoning. And African Americans, even in the face of the devastating rhetoric in Dred Scott, continue to wage a campaign for citizenship into what then becomes the era of the Civil War.

Lerone Bennett Jr., in Before the Mayflower, noted that the Dred Scott ruling was one of “three ominous developments” of the decade. He explained:

The first was a national political decision called the Compromise of 1850. This compromise, introduced in Congress by Henry Clay, provided for “the final settlement” of the slavery controversy on the basis of a trade-off between free and slave states and the enactment of a national Fugitive Slave Law, which threatened the lives and liberties of almost all free Blacks. There then followed a second “final” settlement, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which opened Northern territory to settlement by slaveholders. The third development, no less ominous, was a U.S. Supreme court decision which said, in the case of Dred Scott (1857), that no Black could be a U.S. citizen and that Black people had no rights in America that white people were bound to respect. The net effect of all this as the de facto nationalization of the slave system.

Often left out of the traditional narrative is Harriet Scott, who filed a petition for freedom at the same time (April 6, 1846) and with the same lawyer as her husband Dred Scott. They were both deeply concerned for their two daughters. As the cases progressed, the courts decided in 1850 that the final decision made for Dred Scott’s petition would be applied to Harriet Scott’s.

It is also important to note that Harriet and Dred Scott met at Fort Snelling in what is now the state of Minnesota. This counters the misperception of slavery being limited to the South and on plantations. They were enslaved on a U.S. military base by U.S. Army officers. [Read more in Slavery’s Reach: Southern Slaveholders in the North Star State by Christopher P. Lehman.]

Learn More

“From Dred Scott to Ferguson: Missouri at the Heart of a National Debate” by Blair Kelly in CommonDreams.org.

Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America by Martha Jones. This book offers a vital examination of the fight for citizenship rights by African Americans before, after, and in light of the Dred Scott ruling.

A People’s History of the Supreme Court: The Men and Women Whose Cases and Decisions Have Shaped Our Constitution by Peter Irons. This book has two full chapters on Dred Scott v. Sandford.

Find more related resources below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn