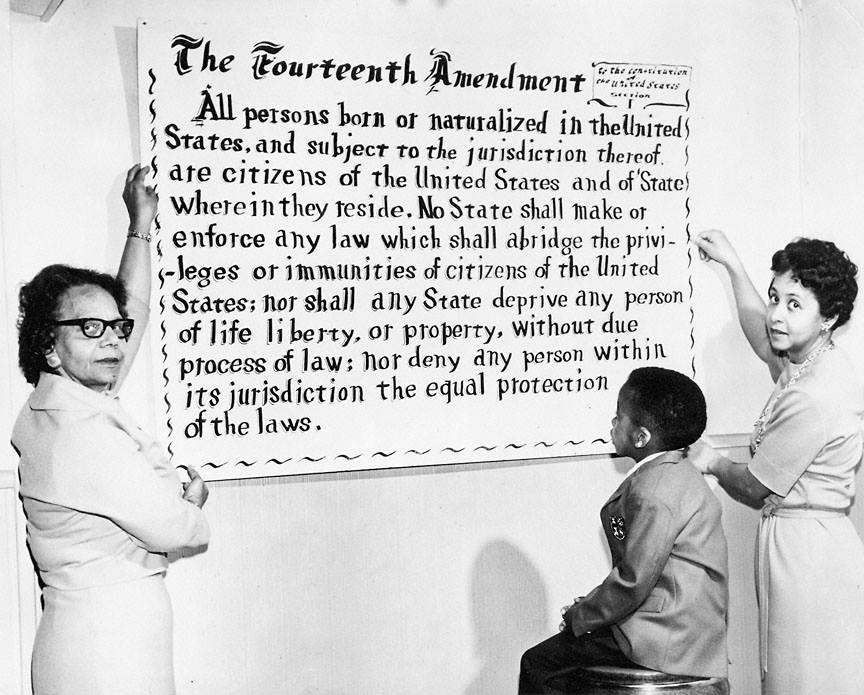

In 1883, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Civil Rights Act of 1875, forbidding discrimination in hotels, trains, and other public spaces, was unconstitutional and not authorized by the 13th or 14th Amendments of the Constitution. The ruling read in part:

The XIVth Amendment is prohibitory upon the States only, and the legislation authorized to be adopted by Congress for enforcing it is not direct legislation on the matters respecting which the States are prohibited from making or enforcing certain laws, or doing certain acts, but it is corrective legislation, such as may be necessary or proper for counteracting and redressing the effect of such laws or acts.

The XIIIth Amendment relates to slavery and involuntary servitude (which it abolishes); . . . yet such legislative power extends only to the subject of slavery and its incidents; and the denial of equal accommodations in inns, public conveyances and places of public amusement (which is forbidden by the sections in question), imposes no badge of slavery or involuntary servitude upon the party, but at most, infringes rights which are protected from State aggression by the XIVth Amendment.

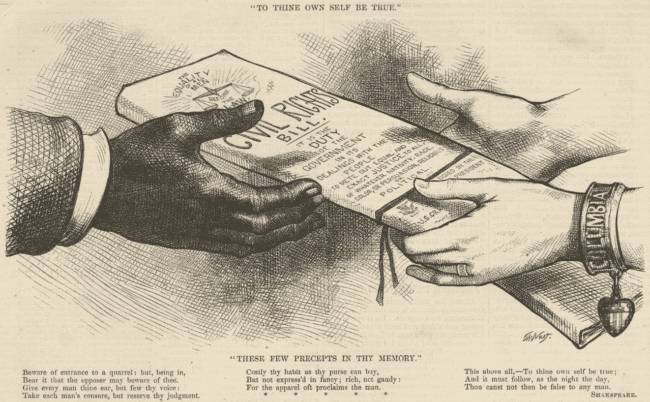

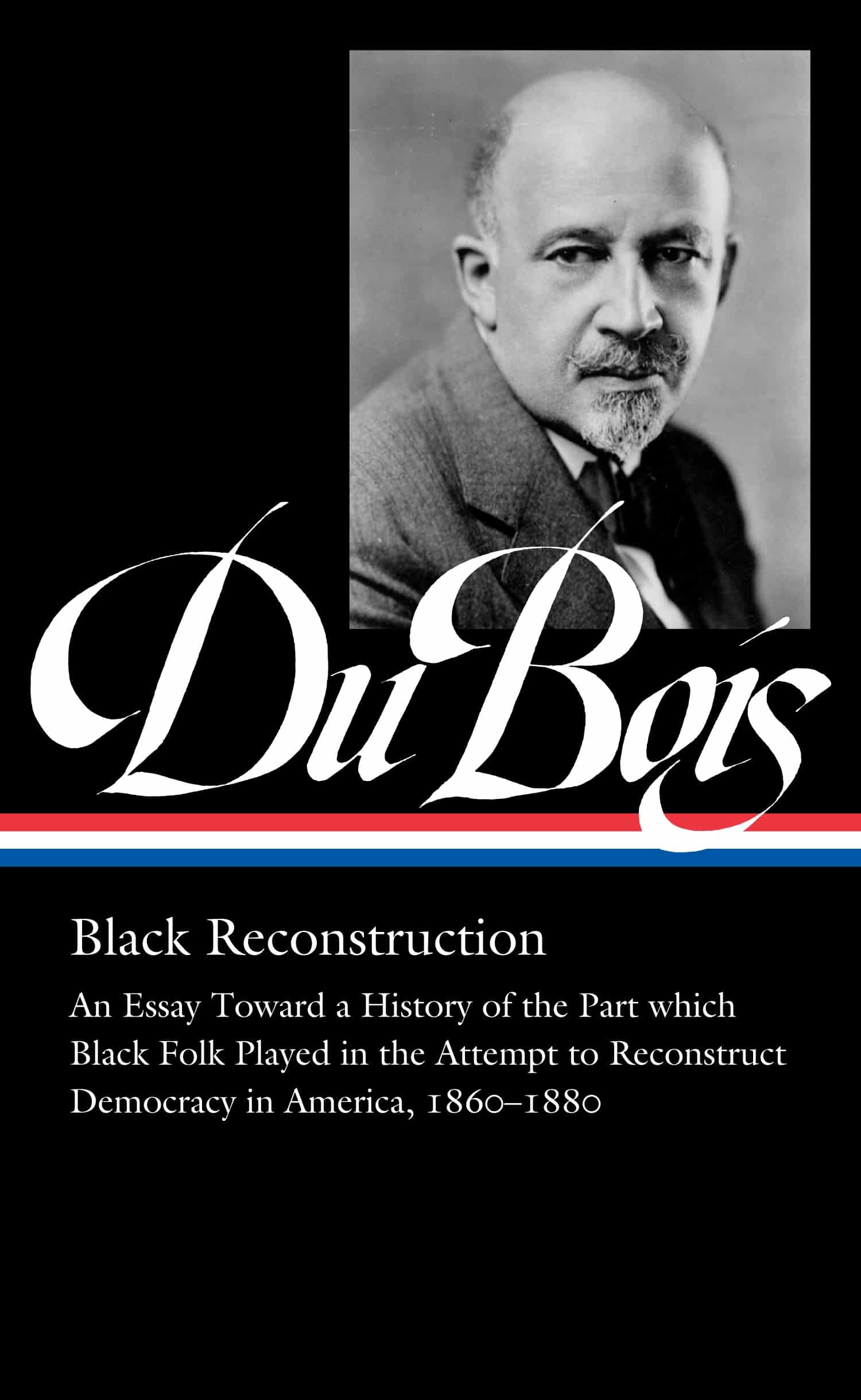

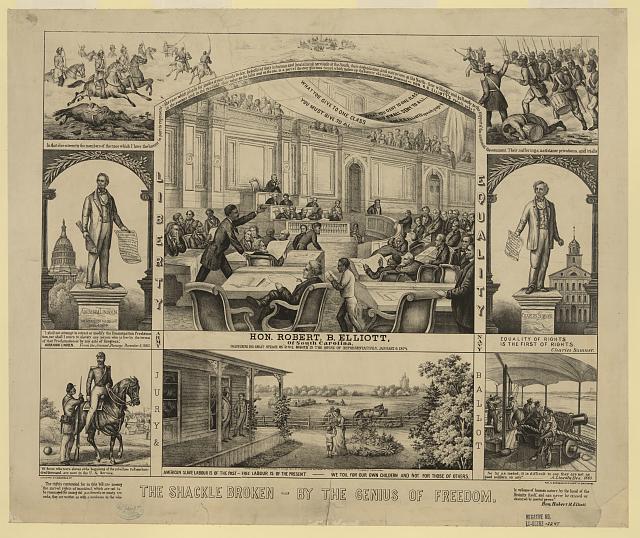

Engraving by Thomas Nast from Harper’s Weekly, 24 April 1875. Source: Mass. Historical Society

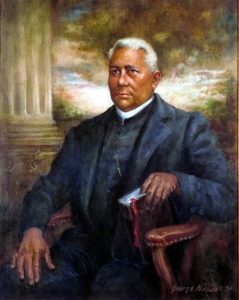

The decision outraged the Black community and many whites as well, for they felt it opened the door to legalized segregation. Bishop Henry McNeal Turner raged at the court for its decision:

The world has never witnessed such barbarous laws entailed upon a free people as have grown out of the decision of the United States Supreme Court, issued October 15, 1883. For that decision alone authorized and now sustains all the unjust discriminations, proscriptions and robberies perpetrated by public carriers upon millions of the nation’s most loyal defenders. It fathers all the ‘Jim-Crow cars’ into which colored people are huddled and compelled to pay as much as the whites, who are given the finest accommodations. It has made the ballot of the Black man a parody, his citizenship a nullity and his freedom a burlesque. It has engendered the bitterest feeling between the whites and Blacks, and resulted in the deaths of thousands, who would have been living and enjoying life today.

One of the justices on the court, John Harlan, gave a now-famous dissent, writing,

Whereas it is essential to just government we recognize the equality of all men before the law, and hold that it is the duty of government in its dealings with the people to mete out equal and exact justice to all, of whatever nativity, race, color, or persuasion, religious or political; and it being the appropriate object of legislation to enact great fundamental principles into law; I am of opinion that such discrimination is a badge of servitude, the imposition of which congress may prevent under its power, through appropriate legislation, to enforce the thirteenth Amendment; and consequently, without reference to its enlarged power under the fourteenth Amendment, the act of March 1, 1875, is not, in my judgment, repugnant to the constitution.

African Americans would have to wait until 1964 before Congress would again pass a civil-rights law, this time constitutionally acceptable, that would forbid discrimination in public accommodations, employment, and unions.

This entry is from the The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow on THIRTEEN.

Additional Resource:

“The 1883 Civil Rights Cases, the 14th Amendment, and Jim Crow New York” by Alan Singer (New York Almanack)

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn