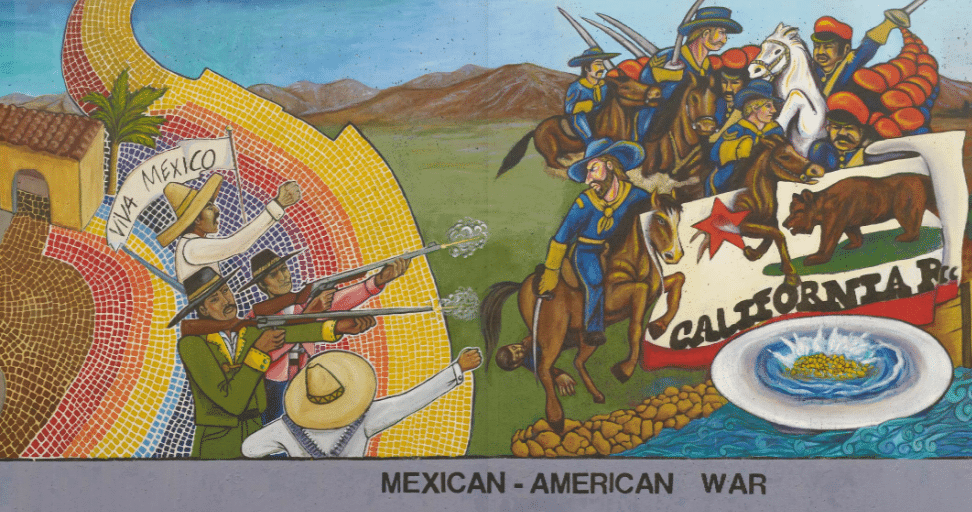

Painting from mural on Mexican history by Diego Rivera at the National Palace.

By Sudie Hofmann

I recently came across a flier in an old backpack of my daughter’s: Wanted: Committee Chairs for this Spring’s Cinco de Mayo All School Celebration.

The flier was replete with cultural props including a sombrero, cactus tree, donkey, taco, maracas, and chili peppers.

Seeing this again brought back the moment when, years earlier, my daughter had handed the flier to me, and I’d thought, “Oh, no.” The local K-6 elementary school’s Parent Teacher Student Association (PTSA) was sponsoring a stereotypical Mexican American event.”

There were no Chicana/o students, parents, or staff members who I was aware of in the school community and I was concerned about the event’s authenticity. I presumed the PTSA meant well, and was attempting to provide a multicultural experience for students and families, but it seemed they were likely to get it wrong.

After making some inquiries, I was told the school wanted to celebrate Cinco de Mayo because it was Mexico’s Independence Day. However, Cinco de Mayo is actually Battle of Puebla Day, commemorating the defeat of Napoleon III in 1862. Mexico’s Independence Day is Sept. 16. I wrote the school and asked if they might consider canceling the event. I was concerned that the stereotypes associated with Chicana/os, such as fast-food items, piñatas, sombreros, and serapes would be central to the event. Unfortunately, I was correct.

Continue reading “Rethinking Cinco de Mayo.”

More Reading

Howard University Professor Dr. Greg Carr tweeted, “On #CincoDeMayo remember Battle of Puebla & Mexico’s anti-slavery roots & Black-Brown unity in resistance to settler colonialism. The holiday marks the fact that, on this day in 1862, Mexico struck a blow against the invaders.” Carr suggests the following readings for further study on the topic.

|

Black and Brown: African Americans and the Mexican Revolution, 1910-1920 by Gerald Horne The Mexican Revolution was a defining moment in the history of race relations, impacting both Mexican and African Americans. For Black Westerners, 1910–1920 did not represent the clear-cut promise of populist power, but a reordering of the complex social hierarchy which had, since the 19th century, granted them greater freedom in the borderlands than in the rest of the United States. [Publisher’s description.] |

|

Bearing Arms for His Majesty: The Free-Colored Militia in Colonial Mexico by Ben Vinson III This study uses the participation of people of African ancestry in New Spain’s militias as a prism for examining race relations, racial identity, racial categorization, and issues of social mobility for racially stigmatized groups in colonial Mexico. By 1793, nearly 10 percent of New Spain’s population was made up of people who could trace some African ancestry. |

|

The African Presence in México: From Yanga to the Present by curators Césareo Moreno and Sagrario Cruz Carretero Almost a century after Africans arrived in Mexico in 1519, Yanga, an African leader, founded the first free African in the Americas (January 6, 1609). No exhibition has showcased the history, artistic expressions, and practices of Afro-Mexicans in such broad scope as this one, which includes a comprehensive range of artwork from the 18th Century Colonial Caste Paintings to contemporary artistic expressions. |

|

The Counter Revolution of 1836: Texas slavery & Jim Crow and the Roots of American Fascism by Gerald Horne Texas has become a leader of ultra-right forces nationally – especially since the 1950s – when the notorious oilmen were the bulwark of support for McCarthyism. One lesson from Texas history, though, is that repression was so severe because resistance was so daunting – a lesson to keep in mind as this century unfolds. |

Find more resources below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn