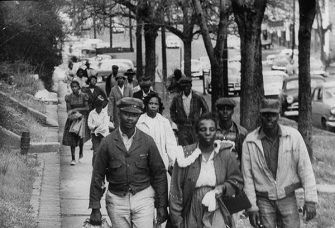

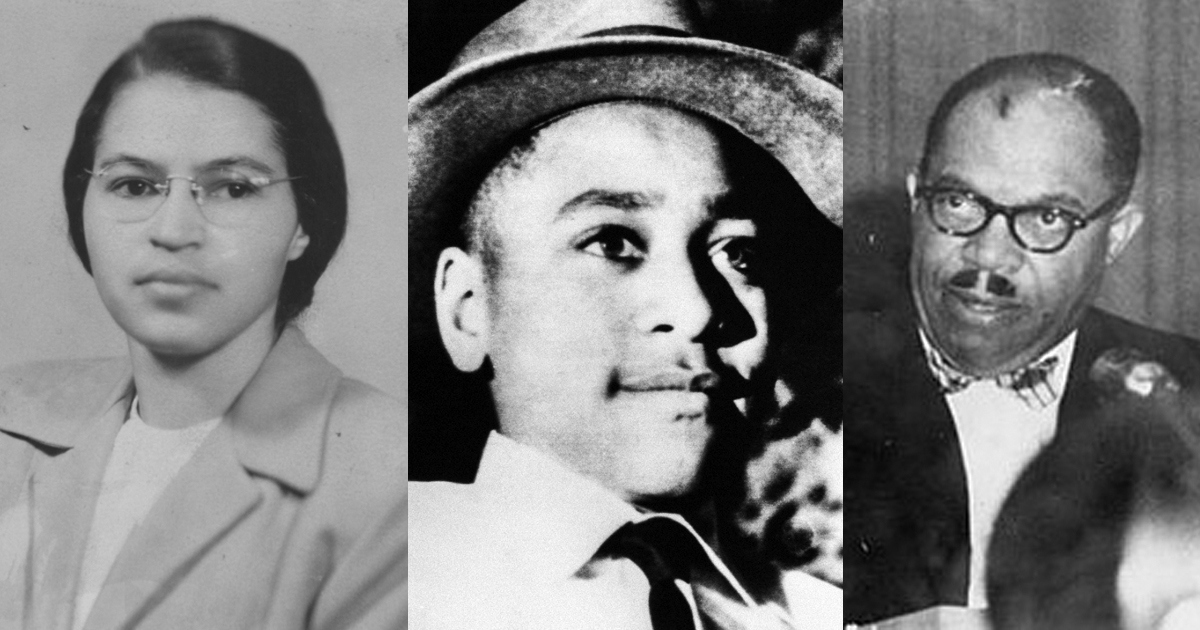

Walking to work, 1955. ©Don Cravens/Time Life/Getty Images.

On Dec. 5, 1955 the Montgomery Bus Boycott began. It is one of the most powerful stories of organizing and social change in U.S. history.

Yet many people still associate it with an isolated act by Rosa Parks, without the context of Parks’ own life of activism, the decades of protests of Jim Crow on public transportation across the country, nor the role of the Women’s Political Council of Montgomery.

Out of Montgomery’s 50,000 African American residents, 30,000-40,000 participated in the boycott. For 381 days, they walked or bicycled or car-pooled, depriving the bus company of a substantial portion of its revenue.

In order to maintain the boycott, the Montgomery Improvement Association was born. The MIA created an elaborate carpool system, designating 40 pickup stations across town where people could go to get a ride. Police and local whites constantly harassed the car pool with tickets and violence. But the community pressed on.

One of the tactics the city used to try to derail the boycott was to dredge up an old law prohibiting organized boycotts. Hoping to break the carpool system and criminalize its leaders , at the end of February 1956, the city indicted 89 boycott leaders including Parks. As a show of power and support, many boycott organizers, including Parks and Nixon, chose to turn themselves in. . . .

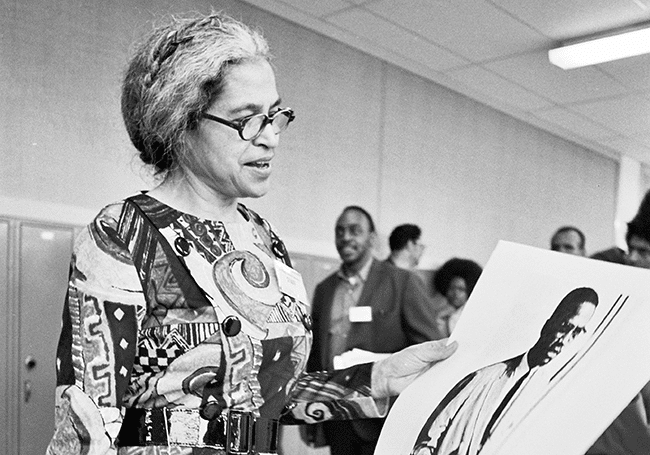

Even after the boycott’s successful end, Rosa and Raymond Parks still couldn’t find work [they had both lost their jobs about five weeks into the boycott] and the family continued to get death threats. Continue reading Rosa Parks Biography by Jeanne Theoharis, author of The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks.

It is important for students to know that the Montgomery Bus Boycott was a demand for much more than desegregation, as described here by Danielle McGuire in “More Than a Seat on the Bus.”

In truth, the Montgomery Bus Boycott was a protest against racial and sexual violence, and Rosa Parks’s arrest on December 1, 1955 was but one act in a life devoted to the protection and defense of Black people generally, and Black women specifically. Indeed, the bus boycott was, in many ways, the precursor to the #SayHerName twitter campaigns designed to remind us that the lives of Black women matter.

In 1997, an interviewer asked Joe Azbell, former city editor of the Montgomery Advertiser, who was the most important person in the bus boycott. Surprisingly, he did not say Rosa Parks. “Gertrude Perkins,” he said, “is not even mentioned in the history books, but she had as much to do with the bus boycott as anyone on earth.” On March 27, 1949, Perkins was on her way home from a party when two white Montgomery police officers arrested her for “public drunkenness.” They pushed her into the backseat of their patrol car, drove to a railroad embankment, dragged her behind a building, and raped her at gunpoint.

Left alone on the roadside, Perkins somehow mustered the courage to report the crime. She went directly to the Holt Street Baptist Church parsonage and woke Reverend Solomon A. Seay Sr., an outspoken minister in Montgomery. “We didn’t go to bed that morning,” he recalled. “I kept her at my house, carefully wrote down what she said and later had it notarized.” The next day, Seay escorted Perkins to the police station. City authorities called Perkins’s claim “completely false” and refused to hold a line-up or issue any warrants since, according to the mayor, it would “violate the Constitutional rights” of the police. Besides, he said, “my policemen would not do a thing like that.”

But African Americans knew better. What happened to Gertrude Perkins was no isolated incident. Montgomery’s police force had a reputation for racist and sexist brutality that went back years, and Black leaders in the city were tired of it. When the authorities made clear that they would not respond to Perkins’s claims, local NAACP activists, labor leaders, and ministers formed an umbrella organization called the “Citizens Committee for Gertrude Perkins.” Rosa Parks was one of the local activists who demanded an investigation and trial, and helped maintain public protests that lasted for two months. Read the full article “More Than a Seat on the Bus” and we recommend McGuire’s book, At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance — A New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power.

Read more at Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955-56) at BlackPast.org.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn