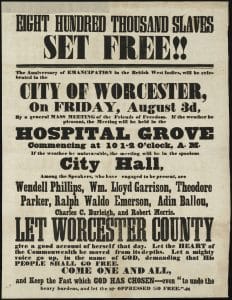

Poster for an event in Worcester, Massachusetts in 1849, to commemorate the end of slavery in the British West Indies.

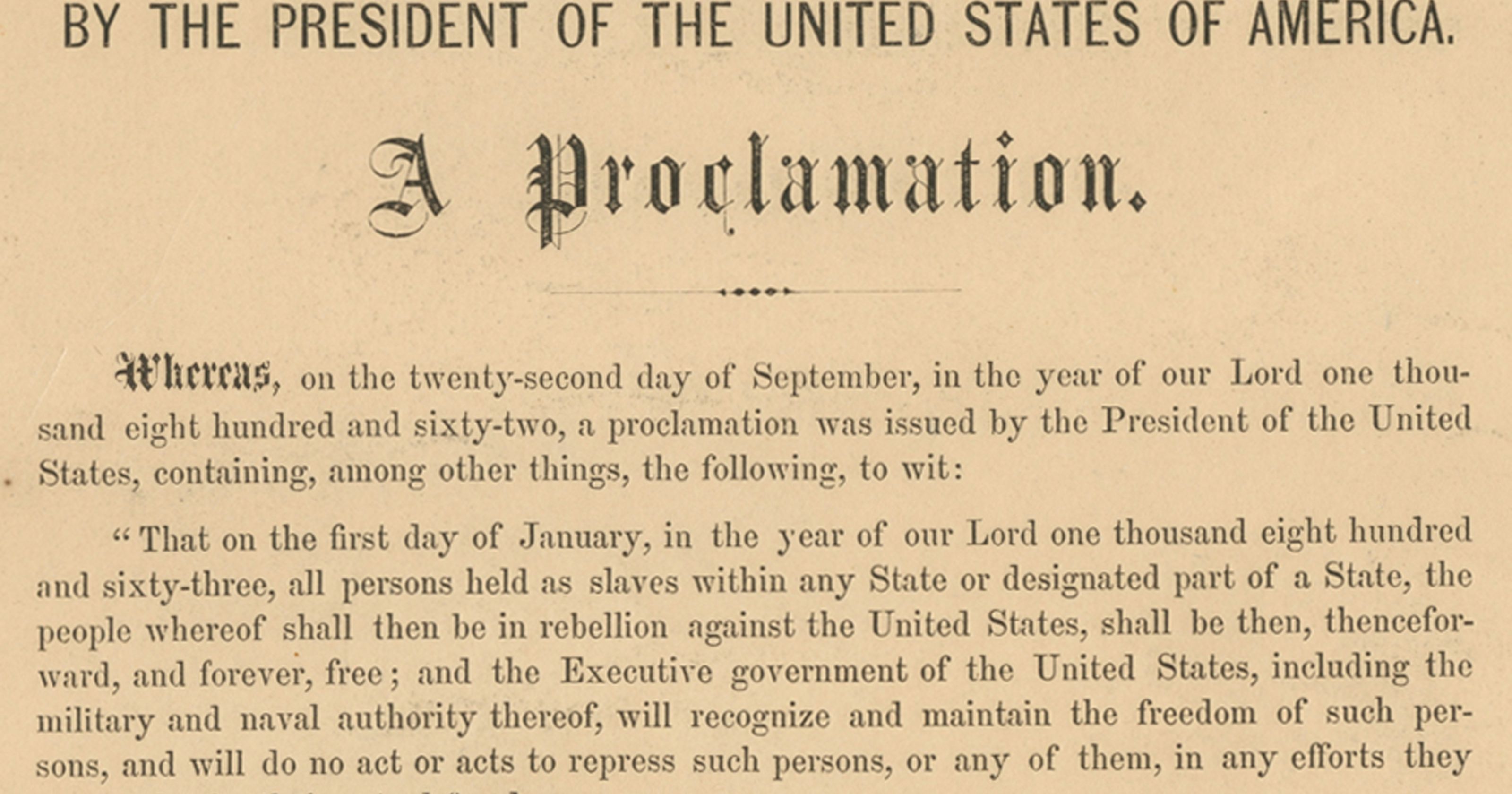

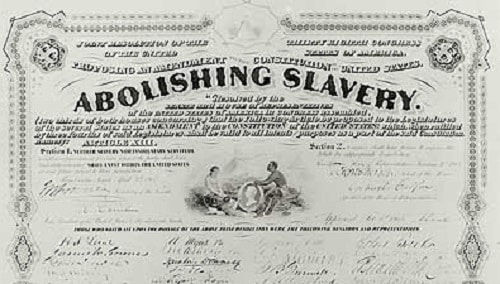

On August 1, 1834, Britain passed the Slavery Abolition Act, outlawing the owning, buying, and selling of humans as property throughout its colonies around the world. While this did not free enslaved people in the United States, it was a source of inspiration and hope for abolitionists. It outlawed slavery in Canada, which became a haven for refugees. Black people in the United States and white abolitionists observed August First Day widely up until the Civil War, and the tradition carried on — to a lesser extent — into the early 20th century.

Tom Zoellner, a professor of English at Chapman University and the author of Island on Fire: The Revolt That Ended Slavery in the British Empire, explains,

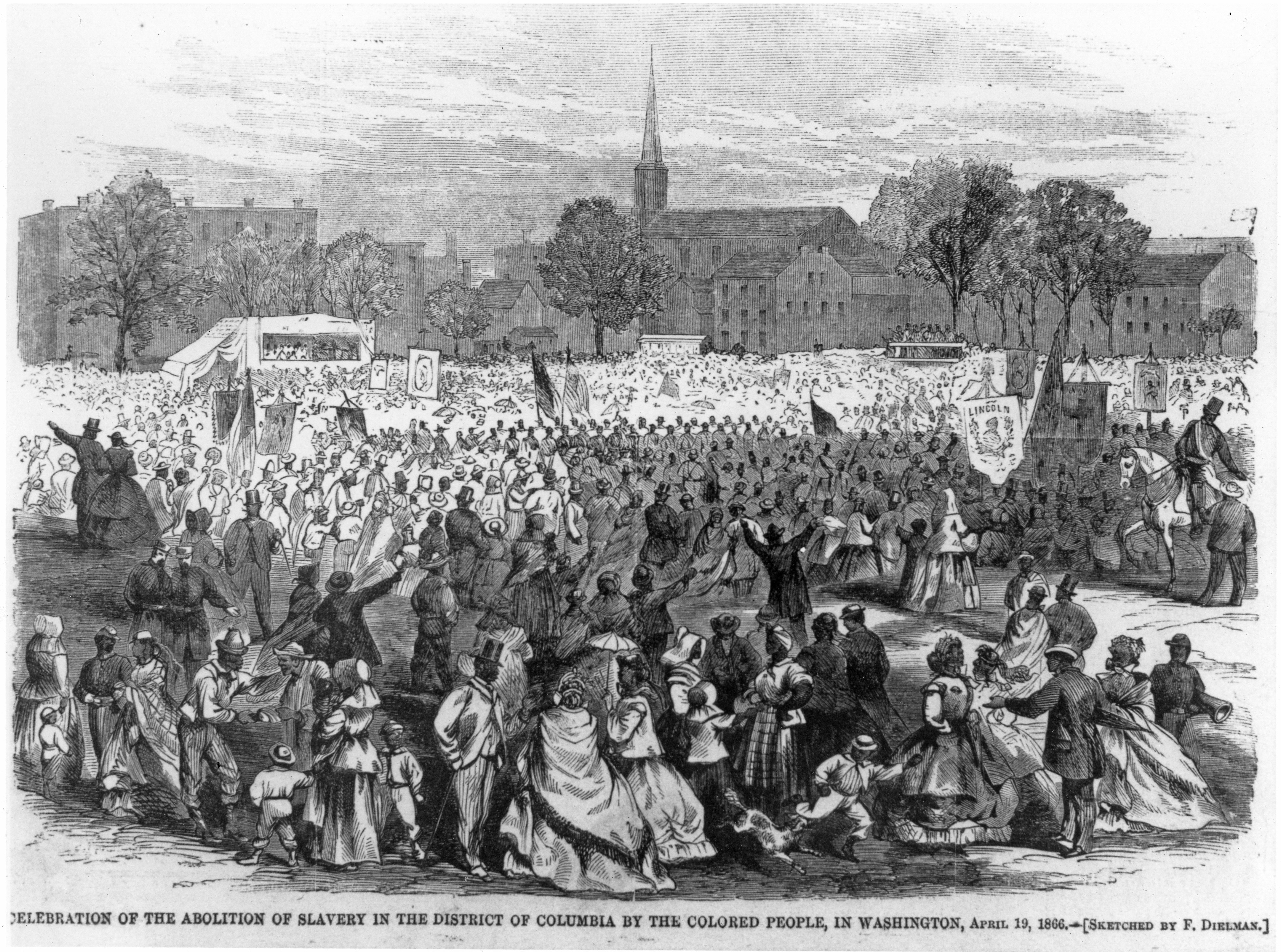

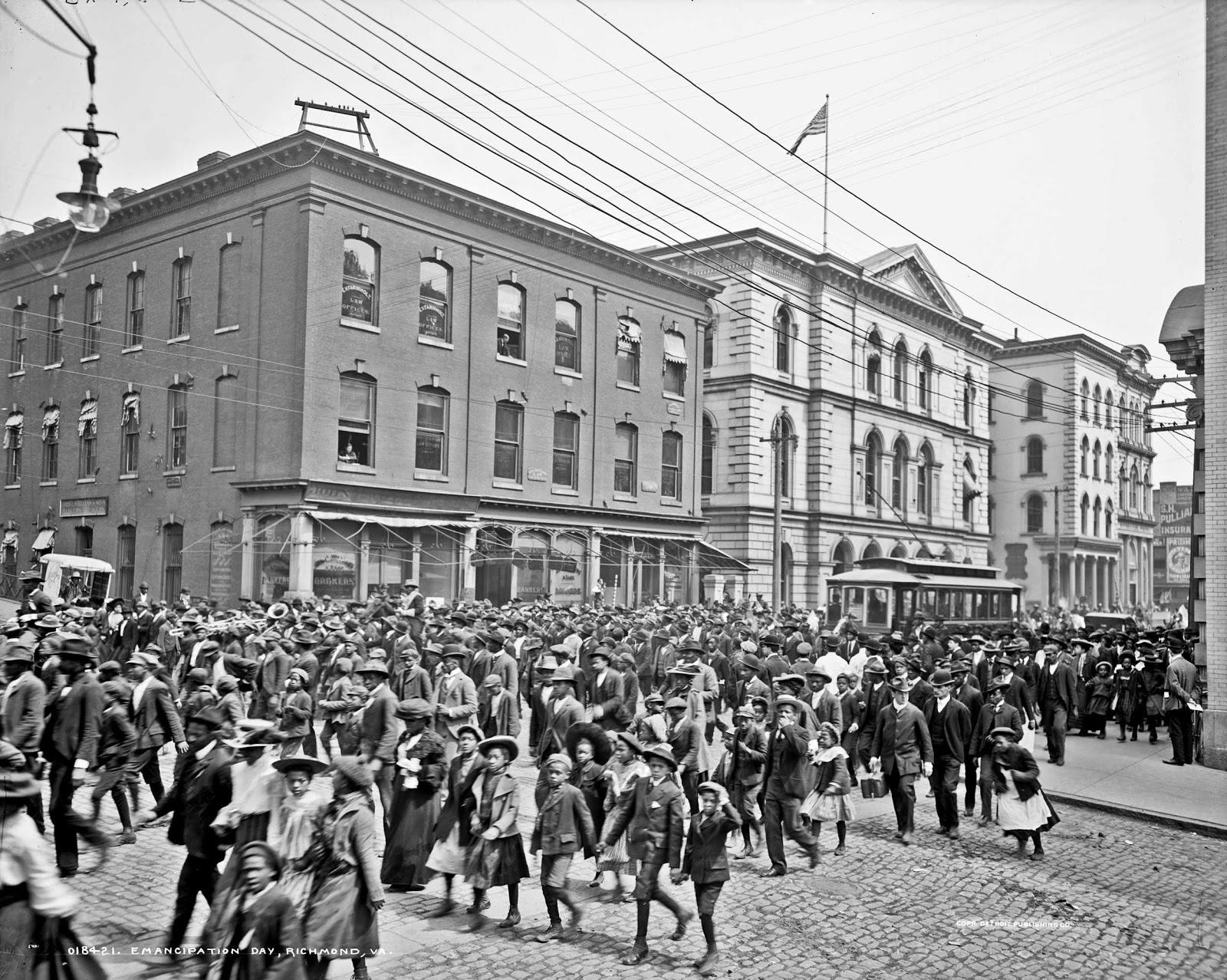

August First Day was once the most important date on the calendar for African Americans during the 19th century. It represented a day more meaningful than the Fourth of July. It was also widely celebrated across the nation with picnics, speeches, dancing, hymns and marches until the beginning of the Civil War. The holiday marked the radical deed of a foreign country: Britain’s passage of the Slavery Abolition Act, which marked the start of freedom for 800,000 enslaved people in all its colonies on Aug. 1, 1834.

…The holiday had its roots in Jamaica, where a five-week revolt led by a Black preacher named Sam Sharpe in 1831-1832 had forced the British Parliament to make a calculated decision that maintaining slavery overseas was simply too expensive. “Let us pray that our brothers and sisters in other lands may be made free,” said the once-enslaved William Gibson in Falmouth, Jamaica, on Aug. 1, 1838.

…The holiday had its roots in Jamaica, where a five-week revolt led by a Black preacher named Sam Sharpe in 1831-1832 had forced the British Parliament to make a calculated decision that maintaining slavery overseas was simply too expensive. “Let us pray that our brothers and sisters in other lands may be made free,” said the once-enslaved William Gibson in Falmouth, Jamaica, on Aug. 1, 1838.

Continue reading Professor Zoellner’s article at the Washington Post.

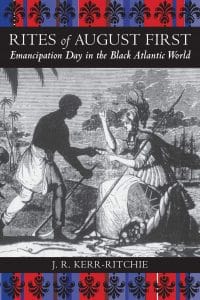

Learn more about August First Day in the book Rites of August First: Emancipation Day in the Black Atlantic World, and article “Whatever Happened to August First?”, both by Howard University professor of history Jeffrey R. Kerr-Ritchie.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn