Change depends on people knowing the truth. Change depends on people speaking that truth out loud. That’s what movements do. Movements educate people to the truth . . . Movements are the way ordinary people get more freedom and justice. — Unita Blackwell, Barefootin’: Life Lessons from the Road to Freedom (2006)

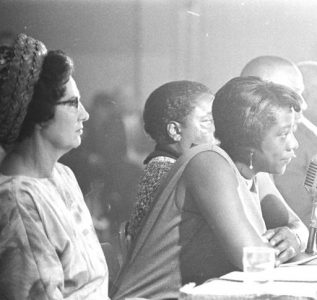

Unita Blackwell speaking at a senate hearing on poverty in Jackson, April 10, 1967. By Jim Peppler. Source: Southern Courier Photo Collection, ADAH

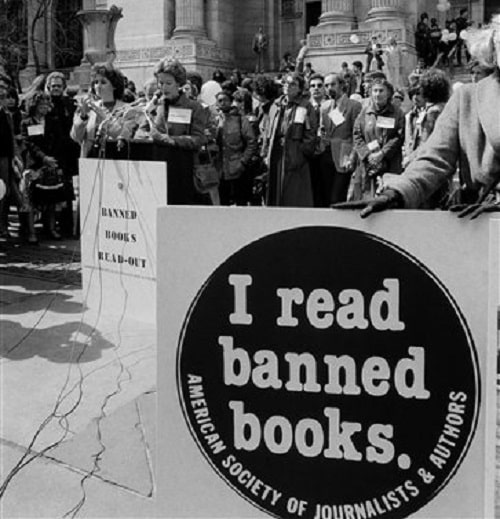

On April 1, 1965, the civil rights suit of Blackwell v. Issaquena Board of Education was filed on behalf of 300 African-American students from several schools across Issaquena County in Mississippi. The students were suspended for wearing and distributing “freedom” buttons after school administrators forbade them. The buttons were from the youth led civil rights organization, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

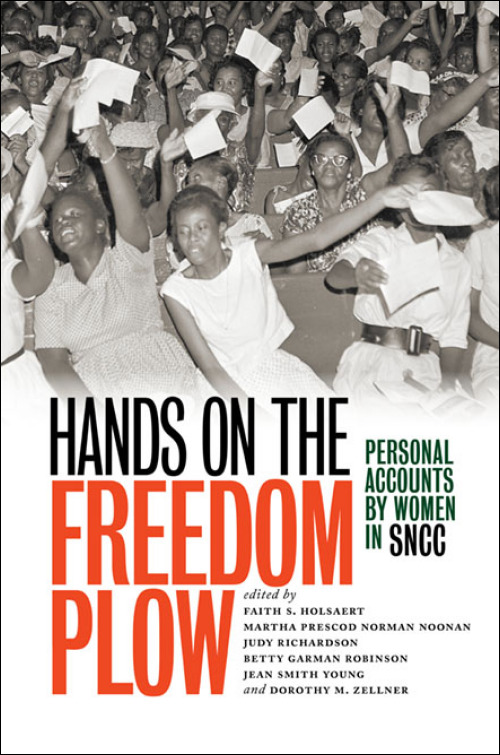

In the days prior to the suspensions, students began wearing the SNCC pins that depicted a black and white hand joined in unity. SNCC had been organizing a grassroots community effort to register more African Americans to vote in the county.

After the students were forbidden to wear or distribute the pins, the students continued to stage protests and boycotts. Many disobeyed the orders to stop wearing the pins which led to the suspensions.

So many kids came to school wearing SNCC pins that we couldn’t count them all. The principal began the day by calling a general assembly. He said that he would listen to no more questions. Then he read from a book a rule saying that, “Any student who disrupts school can be suspended or expelled by the principal.”

He told the students that the SNCC pins were disrupting school. Any student who wore a pin the next day would be suspended, and any student who wore a SNCC pin on Thursday, said the principal, would be expelled and not allowed to go to school anywhere in Mississippi. — Student

More than 300 of the 1,100 students wear pins, as do some of the children in the elementary school. And over in adjacent Sharkey County, some high school students do the same. Again the principal calls an assembly. . . .He suspends the 179 students whose names were taken down on Monday and threatens the same for anyone else who continues to defy the edict against freedom buttons. He tells them they can only return to school if they sign a written promise not to participate in any kind of civil rights activity including wearing SNCC pins. Close to 150 pin-wearing students who have not (yet) been suspended walk out of school in solidarity with those who have been expelled.

[From Civil Rights Movement Archive CRMvet.org]Unita Blackwell, a SNCC field officer and mother to one of the students, decided to launch a legal case in which her husband and son were the plaintiffs. They argued that the schools had violated the students’ First Amendment rights to free speech and political expression of ideas that challenged the racial injustice of the school system. They wanted all suspended students to be allowed to return to school and for the schools to allow students the freedom to wear the SNCC pins. They also demanded that the Issaquena schools implement the Supreme Court ruling of desegregation by the beginning of the 1965 school year.

The federal courts sided with the school board’s disciplinary action of censorship and suspension. They stated that the school’s interest in preventing the interference with school policies trumped the students’ rights of free speech. On the other hand, the court sided with the Blackwells on the need for a desegregation plan for the school district.

It would take another five years for the integration of the schools in Issaquena. Many students and their families continued to boycott the schools because of the court’s ruling. Blackwell, with the support of parents and the local SNCC chapter, offered an alternative form of education in a Freedom School. Here is the description from Civil Rights Movement Archive:

Parents and students begin organizing Freedom Schools in local churches and homes. Older students teach the younger ones. A few SNCC & COFO organizers, and northern white volunteers provide assistance, but the effort is predominantly run by local activists. Freedom Schools elsewhere in the state send books, materials, and expressions of support.

The Issaquena-Sharkey Freedom Schools are different from Freedom Schools that operated in Mississippi last summer because students are teaching themselves. What is happening in these Freedom Schools is that students are beginning to discover that they know a great deal about what they need to know — that is about the things that matter in their lives. This is a revolutionary concept in education. Students can give themselves a better education than the local schools can about what democracy is, what freedom means and how people work together to bring about changes in the society. These are the most relevant things to their lives.” — Judy Walborn, SNCC Staff Education Coordinator. [7]

Many of the Black teachers support the students — most clandestinely, a few more openly. They understand, and share, the students’ frustration with the strictly limited, racially-biased curriculum they are forced to teach. But the white school board can fire them at will, and they have to toe the line or lose their jobs.

Blackwell would continue to challenge racial injustice, championing civil rights in her community long after the court case. In Mississippi, she would become a community improvement leader for the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW) and later become Mississippi’s first African-American woman mayor in 1976.

Read more at CRMvet.org about the court case and the Issaquena County School Boycott.

This case preceded Tinker v. Des Moines.

This summary prepared for CivilRightsTeaching.org by Dawn Keene.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn