On June 21, 1925, the Wichita Monrovians, an all-Black semi-pro baseball team that promised to take on all challengers, bested the Wichita Klan Number 6 — a squad fielded by the white-supremacist Ku Klux Klan terrorist organization. The 10-8 victory came during the height of Jim Crow apartheid in Wichita, Kansas.

Historians know only a few details about the actual game, which was played in front of a “good-sized crowd” on a scorching Sunday, with “searing winds” pushing the temperature to 102 degrees. Brian Carroll wrote in “Beating the Klan” (The Baseball Research Journal, 2008) that the match began as a low-scoring pitching duel but turned into “a see-saw battle” that “ended with a blizzard of scoring.”

Names of the players remain unknown, but apparently both teams agreed to hire two Irish Catholic umpires to avoid appearances of favoritism. In this compromise, the umpires — World War I veterans W. W. “Irish” Garrety and Dan Dwyer — were white, but as Catholics, they belonged to a religion targeted for hate by the Klan.

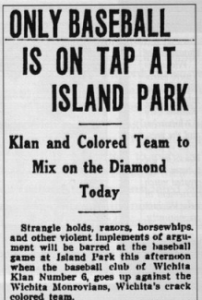

A June 21, 1925, Wichita Beacon news story leading up to the game noted “the wide difference of the two organizations” and cited some bizarre ground rules:

Strangle holds, razors, horsewhips, and other violent implements of argument will be barred at the baseball game at Island Park this afternoon when the baseball club of Wichita Klan Number 6 goes up against the Wichita Monrovians, Wichita’s crack colored team.

The article also says that the “umpires have been instructed to rule any player out of the game who tries to bat with a cross.”

How the unlikely sporting event came about is not known, but historians have offered informed speculation as well as discussed its cultural context.

Wichita’s Island Park baseball stadium. Source: Wichita Public Library.

Although Kansas was admitted to the Union in 1861 as a free state, “segregation was firmly entrenched” by the 1920s, according to the article “Jim Crow Strikes Out,” by historian Jason Pendleton, who noted that the Klan had a statewide membership of nearly 100,000 by 1924, with about 5,000 in Wichita. The Wichita chapter’s oppressive agenda included the statement “no employment of Negroes under any circumstances.”

However, fortunes were changing for the Klan in Kansas. In January 1925, the state’s Supreme Court ruled that the Klan was a sales organization, not a benevolent society, so it could not legally operate in the state without an official charter. Then, on June 3 that year, the state rejected the Klan’s application for a charter.

Meanwhile, William Allen White, the legendary newspaper publisher of the Emporia Gazette was writing a series of editorials denouncing the Klan and, in 1924, mounted an independent campaign for governor on an anti-Klan platform. At times, he described the Klan as a “self-constituted body of moral idiots” and a “profitable hate factory and bigotorium.” White was not elected, but he believed that his candidacy helped change public opinion about the Klan.

The downward slide of the Klan in Kansas was likely a key factor in the Klan’s interest in playing baseball against the Wichita Monrovians. Historians hypothesize that the challenge was part of a last-gasp publicity stunt by the Klan for two purposes: to demonstrate white superiority and to improve the Klan’s image in Kansas. “The Klan was desperately trying to prove it was a positive influence on society,” writes Fletcher Powell in The KKK and Baseball History.

The Monrovians accepted the challenge for several reasons: The team, named in honor of the capital of Liberia, had once played in the Colored Western League, a sort of minor league among the Negro Leagues, but the Colored Western League had collapsed in 1923. That left the Monrovians to create their own schedule, largely by barnstorming through the Midwest. Money was also a factor, with Monrovian players needing to be paid — and the team was committed to donating some proceeds to charitable causes, such as the Phyllis Wheatley Children’s Home in Wichita.

In addition, baseball games were an important family social outing in the Black community at the time. In Wichita, that usually meant “a place to socialize and be comfortable among other Blacks without feeling the stinging pain of racism,” writes Jason Pendleton, who notes that the Monrovians had their own downtown Wichita stadium — a rarity among Black-owned teams.

The game between the Monrovians and the Klan, however, was played at the city-owned Island Park stadium, located on Ackerman Island in the Arkansas River, which at the time tolerated interracial activities.

As Ron Bolton writes for BaseballHistoryComesAlive.com, the Monrovians saw the game as an “opportunity to stick it to the bigots.” He adds: “Victory was theirs and hate had lost the day.”

By Michael Knepler, who prepares periodic #tdih posts for the Zinn Education Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn