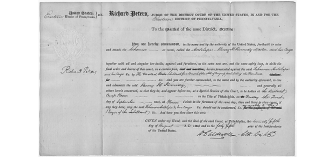

Writ of Attachment in the Trial of “The Antelope”

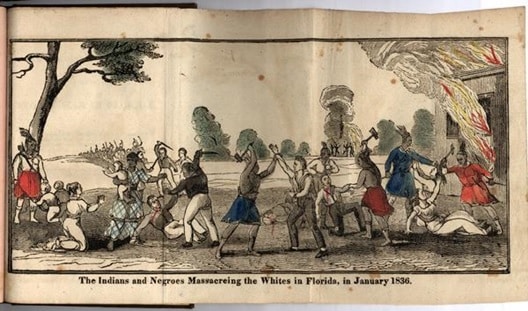

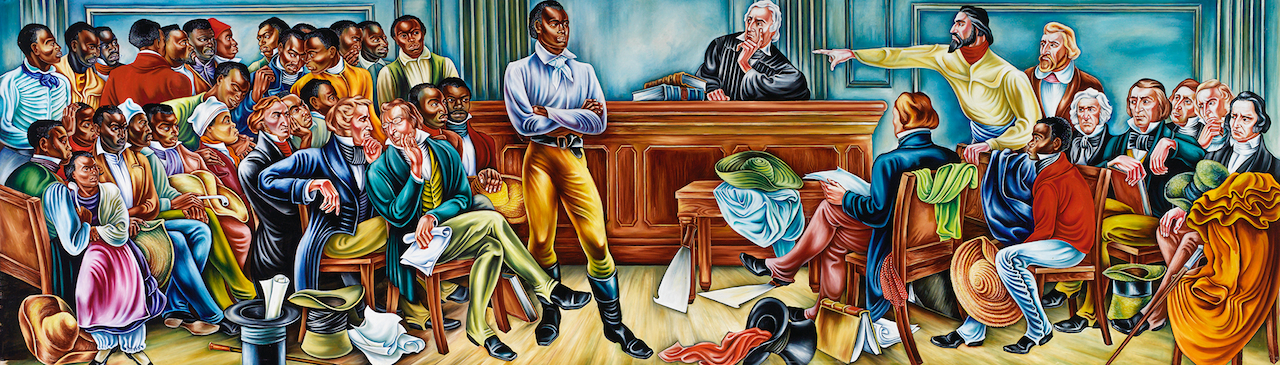

On June 29, 1820 (19 years before the famous Amistad case), 281 Africans aboard The Antelope were brought to Savannah by the U.S. Treasury. The average age of the captives was about 14, and more than 40% were between the ages of 5 and 10 years old.

Rather than being given their immediate freedom as they stated they should be (and should have been), the Africans were imprisoned for seven years while a legal and political battle ensued.

Lawyers and public officials prospered from the case. For example, while imprisoned, the U.S. marshal in Savannah forced the strongest of them to labor (with no pay and under brutal conditions) on his plantation, while at the same time he billed the federal government for the care of the captives.

Of the Africans: 120 died and 2 are unaccounted for. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that 39 be sold into slavery (by the U.S. gov’t.) to raise funds to pay Spain and Portugal and 120 be sent to Liberia to found New Georgia. An overview at the National Archives explains,

Writing for the [Supreme Court] majority, Chief Justice John Marshall concluded that however “abhorrent” the trade may have been, it had “claimed all the sanction which could be derived from long usage and general acquiescence.”

For this reason, the United States was obliged to recognize the rights of other nations to participate in the slave trade. However, because a number of the Africans in question were captured from aboard an American vessel, the United States would retain possession of a portion of their total. Those Africans that were placed in U.S. custody were returned to Africa the following year. The Africans that remained were sold to American slave owners and their proceeds delivered to the Spanish and Portuguese claimants as restitution for their losses.

The full (and painful) decision can be read online, The Antelope, 23 U.S. 66 (1825).

Here is more detailed description from a review of Dark Places of the Earth: The Voyage of the Slave Ship Antelope by Jonathan M. Bryant.

In 1820, a suspicious vessel was spotted lingering off the coast of northern Florida, the Spanish slave ship Antelope. Since the United States had outlawed its own participation in the international slave trade more than a decade before, the ship’s almost 300 African captives were considered illegal cargo under American laws.

In 1820, a suspicious vessel was spotted lingering off the coast of northern Florida, the Spanish slave ship Antelope. Since the United States had outlawed its own participation in the international slave trade more than a decade before, the ship’s almost 300 African captives were considered illegal cargo under American laws.

But with slavery still a critical part of the American economy, it would eventually fall to the Supreme Court to determine whether or not they were slaves at all, and if so, what should be done with them.

Bryant describes the captives’ harrowing voyage through waters rife with pirates and governed by an array of international treaties. By the time the Antelope arrived in Savannah, Georgia, the puzzle of how to determine the captives’ fates was inextricably knotted. Set against the backdrop of a city in the grip of both the financial panic of 1819 and the lingering effects of an outbreak of yellow fever, Dark Places of the Earth vividly recounts the eight-year legal conflict that followed, during which time the Antelope‘s human cargo were mercilessly put to work on the plantations of Georgia, even as their freedom remained in limbo.

When at long last the Supreme Court heard the case, Francis Scott Key, the legendary Georgetown lawyer and author of “The Star Spangled Banner,” represented the Antelope captives in an epic courtroom battle that identified the moral and legal implications of slavery for a generation.

Four of the six justices who heard the case, including Chief Justice John Marshall, owned [enslaved people]. Despite this, Key insisted that “by the law of nature all men are free,” and that the captives should by natural law be given their freedom. This argument was rejected. The court failed Key, the captives, and decades of American history, siding with the rights of property over liberty and setting the course of American jurisprudence on these issues for the next thirty-five years. The institution of slavery was given new legal cover, and another brick was laid on the road to the Civil War.

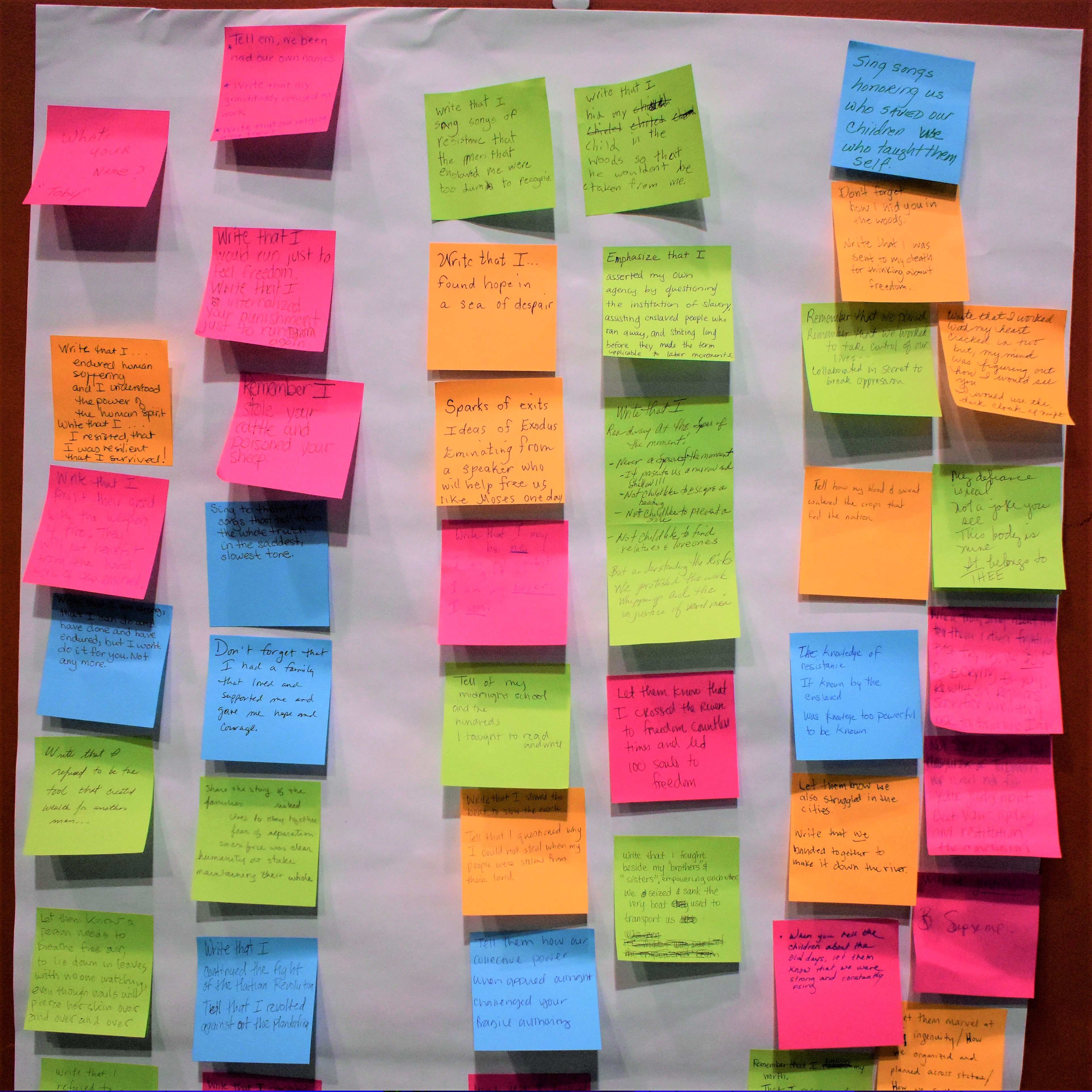

Let us know if you have taught about this case. Find related teaching resources below on resistance to slavery and reparations.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn