White Buffalo Girl’s gravesite, still looked after by members of the town and members of the Ponca Nation. Source: Rails to Trails

On June 10, 2018, along the “Trail of Tears” in Neligh, Nebraska, a farmer signed a deed to return ancestral land to the Ponca Tribe. Nearby is the gravesite of White Buffalo Girl, an 18-month-old Ponca girl who died during the forced removal of the Ponca Nation.

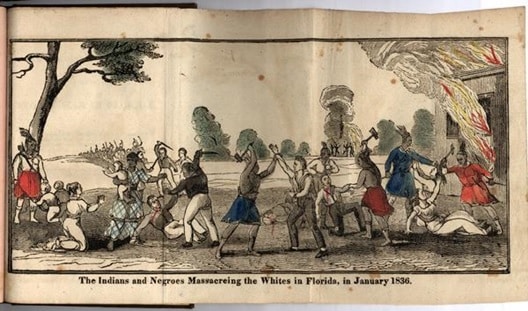

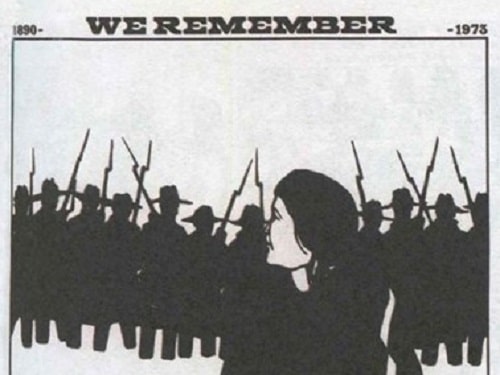

In 1877, the Ponca Nation was forced by the federal government to leave their home of Nishu’de ke (also known as Missouri) to relocate 600 miles south into present-day Oklahoma. Their forced removal took 55 days and killed several — including White Buffalo Girl — and is known as the Ponca Trail of Tears.

Author and researcher Joe Starita writes that the weather conditions were awful. It was “damp, cold, and dreary. What roads existed were muddy from torrential downpours.” About a week into their forced removal, the Ponca set up camp along the Elkhorn River, near the present-day town of Neligh.

On May 23, 1877, White Buffalo Girl died, most likely due to pneumonia. The Neligh town carpenter was asked to make a coffin for White Buffalo Girl, and she was buried the next day under a white cross. Her parents, Moon Hawk and Black Elk, were forced to continue on; they were not allowed to stay with the grave of their child.

As they were leaving, Black Elk asked the people of Neligh to take care of his daughter’s grave: “I want the whites to respect the grave of my child just as they do the graves of their own dead. [We] don’t like to leave the graves of [our] ancestors but we had to move and hope it will be for the best. I leave the grave in your care. I may never see it again. Care for it for me.”

A third Ponca person died during this relocation, one of thousands of deaths caused by the federal government’s decision to forcibly remove hundreds of thousands of Indigenous peoples both during the Trail of Tears and after. Today, the site of White Buffalo Girl’s gravesite is still honored as members of the Neligh community have been stewarding the site for the last 144 years.

The 2014 harvest marked the first time in 137 years that Red Ponca corn was grown. Source: Rails to Trails

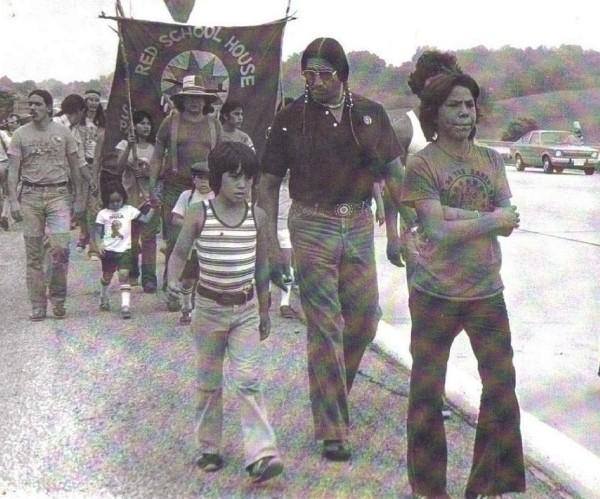

As detailed by Scott Stark in his article “The Legacy of White Buffalo Girl, and the Resiliency of a People,” in 2013, farmer Art Tanderup retired on his wife’s farm just outside of Neligh, when they found out that the Keystone XL Pipeline would be built right across their property. Tanderup and others formed a coalition between farmers, ranchers, and Native peoples called Bold Nebraska that opposed this decision. At one of the events held by this coalition, Tanderup met Mekasi Horinek, a member of the Ponca Nation. Mekasi shared with Tanderup that his grandfather had walked through his farm as an eight-year-old boy during this forced relocation.

During their discussion, Horinek explained that the relocation had been especially brutal because they were forced to leave all of the corn they had harvested that year behind. Tanderup and Horinek decided to plant corn in the middle of the Keystone Pipeline’s proposed route.

Horinek tracked down corn that had come from the final crop planted by the Ponca, which had been saved in medicine bundles by the Lakota. With just two handfuls of sacred red corn, they planted the 137 year old kernels. The first harvest in 2014 was wildly successful, and the ceremonial plantings and harvests have now become an annual event for both the Ponca Nation and non-Ponca people alike. Tanderup and his family formally deeded a portion of his farm to the Ponca Nation, saying that he wanted to make the first steps towards righting the wrongs of their ancestors.

On June 10, 2018, Art and Helen Tanderup deeded a portion of their farm to the Ponca Nation in a public ceremony. Source: Rails to Trails

Mauro, the Ponca Nation’s culture director, emphasizes that the Ponca are very much alive today, all 4,500 of them, and should not be relegated solely to the past. The gravesite still stands in Neligh today, symbolizing not just the atrocities of the Trail of Tears, but what is possible in the present when people refuse to forget the events of the past.

This story was prepared by May Kotsen, an intern with the Zinn Education Project in summer 2022.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn