Browse classroom stories by teachers who have used climate justice lessons found at the Zinn Education Project website and see how students — from elementary school to pre-service university programs — respond to lessons about environmental injustice.

How does climate change affect individuals from around the world differently? Highly effective and engaging role playing/scavenger hunt style activity from @ZinnEdProject and @RethinkSchools. pic.twitter.com/tRv2aXoNF5

— Brett Benson (@MrBensonSHS) May 13, 2019

Classroom Stories

I’ve played the Thingamabob Game with my classes two years in a row now, and each time the students are engaged, frustrated, creative, and reflective. Each time I’ve played students come up with new and creative solutions. In reflecting on their experience, students say they lost the game because they cared more about money and the candy reward than about protecting the earth. I ask how we can make real CEOs care about protecting the earth, and students come up with wonderful solutions such as boycotting, charging companies a fine who produce too much CO2, and my personal favorite, making rich companies give away most of their money to pay for installing solar panels for everyone. (There was also one enthusiastic student who proposed we reward companies who did not produce much CO2 by giving candy to their CEOs, just as the rich “CEOs” in our class had gotten candy, which I thought was a charming idea).

There was a particularly memorable moment last year in which six out of the seven teams were cooperating by producing very few Thingamabobs each round, and one company was defecting and maximizing Thingamob production in each round. The other students were getting frustrated, and one girl asked if we could change the rules so that if their class did end up going over the CO2 trigger number, the companies with the least CO2 production ended up with the prize. I made a quick decision and told them yes, if they democratically voted to change the rule, it would change. The girl put her plan to a vote, and it passed by a wide margin. In the end, I think this was an empowering lesson for everyone involved about strength in numbers, recognizing true motives, thinking outside the confines of the system, and organizing.

I’ve kept the Young People’s Climate Conference in my back pocket until we got to the impact of people on environments. The lessons provided by my district were shallow at best, which bothered me, as this problem is affecting the very students in my class.

We first watched some Crash Course and TedEd videos to get our understanding of what climate change was before discussing how we see examples in our current world. The first thing to inevitably come up is the polar bears, which I don’t mind, because it is a great jumping off point for younger students.

From polar bears to deforestation to pollution to smog, we had rich conversations about the effects of global warming. There was fear behind some questions: will we run out of fossil fuels? How will we survive? It’s difficult to stand in front of these wide-eyed kids and say I’m unsure or “yeah, we will,” but I pride myself on honesty. We also talked about greed and how this fuels the decisions people make around us.

We saw a picture of the UN Summit, observing all the leaders huddled around discussing the future of our world. I told them that leaders of countries all get to meet and talk about how we might solve climate change. I compared it to all the principals meeting to talk about their schools — who is missing?

“Us. You.”

“Who spends the whole day in the classroom?”

“Us! You! That’s not fair.”

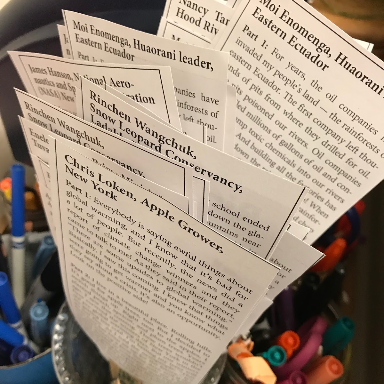

I agreed before introducing our activity: we would be playing the voices who were not heard at this conference. I paired them off, giving each a brief description of their characters to play up the intrigue. I knew my class loved to roleplay so this was right in our wheelhouse.

The assignment begins with a set of Google Slide questions where students introduce their character, tell how climate change affects them and their people, their opinion on it and anything else they want us to know. I saw two straight days of engagement as they compiled their character descriptions from the mixer sheets.

Our final product, the presentation, took place on Friday. Each student was given a “Find somebody who. . .” sheet to complete while their classmates were presenting. We set the scene of a big meeting between various nations and peoples, noting that everyone has a different story and that we need to listen to see whose stories were similar and different than our own.

They were so quiet and respectful of their peers as they went, asking questions after each presentation to clarify or expand. Some even asked questions that my students had to improv! I was pleasantly surprised by the level of detail each student put in and the thought that went into their slides.

We actually had a group of about 20 district personnel and community members come in during the last presentation — which was terrifying! But they handled it like pros, giving the most impassioned speech of the day about what is happening in Eastern Ecuador. It was one of the moments where you know you’ve done right by your kids.

Holistically, this project opened our eyes to the different impacts of climate change across the world better than any video or reading could have. I’m grateful to have this bunch of students who deeply care about our earth and want to make change.

I led an entire unit on environmental justice with my elementary class. We discussed a variety of topics related to environmental justice including food deserts, redlining, climate change, pollution, air and water quality, and public transportation.

When discussing climate justice, we did a mini climate conference based on the Zinn Education Project’s The (Young) People’s Climate Conference lesson.

I separated students into three groups to have three mini-conferences. They presented to their classmates one at a time read directly from the character cards provided by the lesson. I created my own “scavenger hunt” sheet so that each student could take notes on other presentations.

This past winter, I taught a first iteration of a multidisciplinary climate change course, “Climate Change: From Knowledge to Action.” As part of a unit on climate impacts and climate justice, students and I engaged in the Climate Change Mixer activity.

I assigned roles to students the day before the activity and students then took time to do further research on their character and that character’s home place (and how it was being affected by climate change).

During the activity, students got really into their roles and engaged in meaningful conversations with each other. The experience even inspired some students to pursue climate-justice-related topics in their projects later in the term.

As a teacher candidate, I am often encouraged to reuse seasoned teachers’ lesson plans during my practicum placements as I slowly build my own catalog of material. Unfortunately, when teaching a 9th grade geography class last year, the existing materials induced severe climate anxiety and disempowered students. The content was outdated, neoliberal, and never named racial capitalism as one of the root causes of the climate crisis. I was convinced there was a community of educators out there that were generating resources that satisfied my desire to teach to transgress.

When I came across the Zinn Education Project I felt I had found the rad teacher mentor I needed to enact a critical pedagogy in the classroom. I did the Climate Mixer with my students and saw the gears in their brains shifting in real time. We turned climate anxiety into anger and directed our strong feelings towards the global structures maintaining capitalism, colonialism, and white supremacy. My students were engaged, critical, and curious. It felt great to bring movement into the class and learn through such wonderful storytelling. Thank you for these incredible resources!

To introduce our Climate Change unit, we wanted to begin with empathy and a connection to the communities that are most affected by climate change.

My co-teacher and I decided to start with “The Whole Thing is Connected: Plastics and Poverty” from A People’s Curriculum for the Earth. This chapter and series of articles reinforces the idea of environmental racism — the idea that people of color are disproportionately affected by the deleterious affects of climate change, in addition to those who live in poverty (which often intersect, unfortunately). We wanted to ensure that our students understood that, even though recycling plastic seems like a good thing, this seemingly benevolent act could negatively affect those who live in places like “Cancer Alley,” where the toxins of burning plastic bottles (like the one we so carefully and expertly recycled) could cause harm. Empathy is the first step in making change. If your students do not connect to those are affected, there is no motivation to create action steps for change.

This was the first step of our much larger project, the Climate Change Challenge, where we asked students to come up with an innovative and creative solution to reduce the deleterious affects of climate change. One student came up with light switch that turned off if there were no sound waves for more than 30 minutes to save energy, and another group designed an App where you could report environmental “crimes,” similar to the Citizens App. Introducing the topic of climate change with this article on empathy versus straight up textbook content, really connects students to their projects and gives them a more human reason to care and emotionally invest in the future of our earth.

We used materials from the Zinn Education Project, Rethinking Schools, and Teaching for Change with our 7th grade to create an interdisciplinary, experiential project that explored Indigenous Perspectives on Climate Change. It was the perfect way to tie together our humanities unit on Indigenous Perspectives on American History with the STEM unit on deep time and extinction-level events.

Our students prepared for the ‘Don’t Take Our Voices Away’ indigenous people’s climate summit simulation as a final learning demonstration. Taking on the perspectives of various indigenous groups was something our students took seriously as they researched both the cultures and climate challenges faced by the groups. Then, at the summit, they did presentations that explained the priorities and needs of those groups before launching into negotiations about how to best communicate those perspectives with the rest of the world.

Leading up to the summit, we took a climate justice gallery walk using photos shared on the ZEP website, researched indigenous climate activists, and also did the Meet Today’s Climate Justice Activists mixer. Those activities were the perfect scaffold to the summit. Overall, I saw my students develop deep understanding and empathy through the interactive and experiential materials provided by the Zinn Education Project.

I am grateful to have participated in a workshop where I learned how to use them. Now that I am at a school where our model centers experiential project based learning, these materials have become an invaluable resource.

|

I chose to do Food, Farming, and Justice: A Role Play on La Vía Campesina with seniors in International Issues, where they completed the role play for their midterm exam. Our course uses the critical lenses of racism, imperialism, capitalism, and the climate crisis to investigate human rights issues. So, this role play has been a perfect supplement to our work. The materials are so well-designed, thoughtful, challenging, yet accessible, that all of my students have been 100% engaged. Students were so engrossed in the mixer at the beginning of the lesson that they responded with cries of “No! You can’t make us stop!” when I told them class was ending and we could continue our work during the next class. Thank you Zinn Education Project. Your materials help me to be a better teacher and they help my students have more meaningful and memorable experiences in the classroom. |

I used the Don’t Take Our Voices Away role play, about the Indigenous People’s Global Summit, to teach Climate Justice in my 7th and 8th grade global studies class.

The students loved learning about Indigenous groups around the world and deciphering their different perspectives on climate change. The simulation made this so easy. Thank you, Zinn Education Project, for helping me expand my classroom coverage of climate justice and including a global indigenous perspective.

A People’s Curriculum for the Earth provides me with tools to teach environmental issues in new ways that are consistent with the philosophy guiding the Brotherhood-Sister Sol, which is an after-school program for NYC youth. We use the teaching guide to help facilitate lessons plans in the organization’s Environmental Program.

As an Environmental Program Facilitator, my role is to take New York City’s youth into a world of activism, nature exploration, and sustainability through workshops, field trips, and conferences. When I found out about A People’s Curriculum for the Earth, I knew I had to get my hands on it. I am pleased that the lessons found in this curriculum have allowed me to expand on the lessons we run during our sessions and provide a fresh perspective on ways to teach the climate crisis.

In both our high school and junior high school group, we facilitated a lesson on climate justice using the Climate Crisis Mixer lesson plan by Bill Bigelow. Our theme for the first few months was Climate Justice, and we wanted to bring in a lesson that had a big picture perspective.

Since our times with the members are short, we modified the lesson plan by timing members’ conversations with one another, so that they could spend time getting to know all the characters before they were dismissed. The role-playing characters gave members a greater understanding of the nuances in the climate change crisis, and allowed for conversations around the impact of intersectional activism to come up organically. It was great to see that the characters in this lesson plan represented people from all walks of life, which led members to gain a greater understanding that the climate change crisis looks different for everybody, such as Chris Lowken the apple grower, who is not too concerned about climate change since it may be benefiting his crops.

I recently taught the Stories from the Climate Crisis Mixer activity with a class of 8th graders. We began with a brief conversation about what stories they’ve already heard about climate change. Students were then given the choice to partner up or fly solo — there are several low readers in this class, and the reading level of the text was quite high — and students/teams were given time to read their role.

I added one biography to the roles with a local connection: an individual on the Wisconsin Youth Climate Action Team so that students would have a chance to see themselves in the stories.

We then went outside for a walk-and-talk. Students were given the lesson prompts two at a time, and assigned to walk and talk with another person/team to find if they fit the role. For example, the first pair of prompts involve looking for someone who is helped by climate change and someone who is hurt. Pairs chatted for a bit, determined which category they fell in and why, and then walk-and-talked with another person/pair. After they had time to talk about the first prompts, we gave the second set of prompts and, as we walked along the pond, they were to look for connections between water and climate change.

When we returned to the building, I asked them to team up with folks who might have similar situations and might be able to act together. They were able to “match make” their classmates, too, if they could identify roles in other students that fit together. Back in the classroom, we circled up and debriefed the activity. I just wish we’d had more class time to continue the conversation. They had quite a lot to say in their reflections.

Spring semester of 2020, as inklings of the pandemic were just beginning to hit the news, I was helping to facilitate a college study abroad program on Climate Justice. To begin the semester, our group of 30 students crowded into the top floor of a wonderful community space/free library in Oakland, California where we all watched the documentary Necessity. After the film, co-founder and ED of the Climate Defense Project Kelsey Skaggs humbly shared their life journey and relationship to climate work.

Only a few weeks later, after the students learned about the climate effects on the communities of the Mekong Delta while in Vietnam, and had arrived in Morocco to hear from urban activists, COVID-19 interrupted the program and the lockdowns began. For a harrowing week my colleagues and I worked around the clock to organize emergency evacuations for the students while borders were closing everywhere. And while everyone was eventually ‘repatriated,’ much to the credit of their own self-organizing efforts, that schism, that disruption to our learning community was never fully addressed. I, along with many around the globe, lost my livelihood.

Yet, in my long period of unemployment, I began to put into practice some of the things I had previously only taught about in classrooms around the world. Instead of teaching about social movement theory, I became part of social movements. From the George Floyd uprisings to Black Lives Matter to Defund/Abolish the Police to union organizing to Defund Line 3 to Palestinian solidarity, my praxis shifted from the classroom to the streets. Today marks two years and almost two months since I last gathered together in person with a group of students to learn about climate disobedience.

And while I haven’t had the privilege to facilitate this brilliant lesson ‘Teaching Climate Disobedience‘ amidst the collapse of the study abroad industry, I learned how to embody my own practice in a new way. I came into deeper relationship with organizers and activists, with nowhere else to be during the pandemic but in the streets, having each other’s backs. So when Indigenous leadership from Minnesota made the call for all people to gather to uphold their treaty rights, I became part of that story as well. One day soon I will work with students again, and when I facilitate the climate justice mixer, I can share my personal stories of being on the frontlines with Tara Houska and the many thousands of people who stood up to the oil and gas industry in the summer of 2021.

I used the Meet Today’s Climate Justice Activists mixer in my 300-level college class Globalization and the Environment. This allowed me to shift the focus of the class away from doom-and-gloom prognosticating and give students real examples of how positive change can work.

Because the class is small (fewer than 20 students), I pre-selected activists whose work seemed most relevant to the course content. I chose an activist to portray myself and I joined the mixer, balancing out an odd number of students to maintain 1-to-1 conversations at all times.

After class, I had students choose an activist to profile. In their essays, they were asked to analyze how the activist had accomplished their work and with whom they had partnered. Because we had been discussing international political actors (NGOs, IGO, nation-states, TNCs, etc.) in class, I directed them to discuss the activist’s partnerships with any such entities. This essay deepened the connection of the activity to the course content.

The students loved it. When I collected midterm feedback, many students asked for more exercises like the Climate Justice Activist Mixer.

I recently used the Climate Crisis Trial in my Economics of Social Issues class. The trial setting, in which students had to defend themselves against criminal accusations, made this activity highly engaging. It also points out the complexity of the climate change problem: all of the defendants in the activity are guilty to some degree. I assigned the role of prosecutor to a student who is involved in mock trial and he did an amazing job. I will definitely use this activity again.

Connecting climate change to Middle School can be a real challenge. Students often ignore the impacts their choices make and see everything as happening in a far off future. During distance learning last year I attended a virtual conference hosted by the Zinn Education Project regarding their “Stories from the Climate Crisis: A Mixer” lesson. The lesson does a great job of getting students to not only understand personal impacts but to discuss them as well.

My 7th grade Washington State History class used the materials towards the end of our Humans and the Environment lesson. We had been discussing drought and agriculture in our state, as well as the impacts of pollution and human expansion, (one of the stories even discusses this directly). Students were able to understand how the things they do not see everyday can still be happening and how it does not take much to offset the balance of nature.

As a follow up activity, we looked at our own community and students worked in small groups to list everyday actions that teenagers can do to make an impact. This was followed up by a class discussion on what the best solutions are to climate change and how we can all take actionable steps to prevent it. I plan to keep using the lesson in future classes and even to incorporate it into my Creative Writing course.

I have used so many materials from ZEP and Rethinking Schools during my decade as a classroom teacher and for the past two years as an instructional coach and administrator. I LOVE the teaching activities that support U. S. History curriculum, especially role plays (i.e., Potato Famine, Constitution Convention, Reconstructing the South). I modified The People vs. Columbus et al. for my 5th grade students, and together we put Columbus, his soldiers, and the European value system on trial for the genocide of the Taíno.

Inspired by the success of the trial of Columbus, I worked with my 6th grade social studies colleague to put “fast fashion” and sweatshops on trial as well! We read Rethinking Globalization, watched documentaries, and listened to Rebecca Burgess talk about the Fibershed movement in Northern California, and then we created roles based on the real people featured in the documentary “The True Cost.” At the end of their unit on trade in the ancient world, students read about the human impact and environmental devastation caused by today’s fashion industry, and then they put multinational corporations, U.S. consumers, the government, and capitalism on trial.

Finally, I’ve leaned heavily on and been inspired by Bill Bigelow’s People’s Curriculum for the Earth. I modified the Climate Change Mixer for my 5th graders. It was the culmination of our science unit on the carbon cycle. I rewrote each role so that the roles were accessible for lower age readers. Students’ culminating projects were to identify and advocate for one change we could implement at school to reduce our carbon emissions. One student wrote a persuasive letter to our principal outlining new policies about how and when to use electricity in our classrooms. Another student organized a symbolic protest – they advertised a day of wearing green to represent a commitment to reducing carbon emissions through morning announcements, posters, and word-of-mouth.

My teaching and instructional coaching is informed by so many of the activities and publications I’ve found on the Zinn Education Project website! Thank you so much for helping me bring a critical pedagogy to students as young as ten!

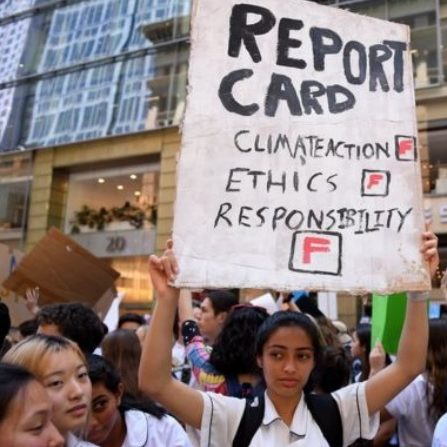

I teach Regents Earth Science to 8th graders in middle school. We held a Climate Mixer to recognize the Global Climate Strike on September 20, 2019.

What I loved about the mixer activity is that students were practicing relationship skills, educating one another about the far-reaching effects of climate change, and considering multiple perspectives on critical issues.

One change that I made to the lesson is that we took a walk outside and had our mixer outside in front of the school. I have found that holding lessons outdoors improves student’s social awareness and motivation.

In my Civics class, which is a semester-long class for upperclassmen, I chose to have my students do Bill Bigelow’s Climate Crisis Mixer as their final project.

My students learned of their “character” the day before the lesson and took the time to prepare for the mixer by researching their roles. We held the role play in the student center, and some students brought snacks and drinks. It was a good way to end the semester and a different way for my students to achieve a final grade.

I’m a Participation in Government teacher at Metropolitan Expeditionary Learning School, a public 6-12 school in Queens, New York. We have some latitude to design our own curriculum at my school, and given our motto as a “school for a sustainable city,” with a focus on designing learning experiences around environmental and social justice, we work to thread the climate crisis into many of our case studies across the disciplines.

This year, we wanted to kick off the semester in Government class by thinking about ways in which people traditionally, and non-traditionally, “participate in government.” We also wanted to explore on-going fights where communities rise up against the confluence of big business, fossil fuel companies, lobbyists, and dark money to fight to protect the Earth. The Zinn Education Project’s Teach Climate Justice resources were a boon to spark our curricular thinking.

Using the Don’t Take Our Voices Away role play as inspiration, we decided to teach and learn deeply about the Dakota Access Pipeline Fight as a way to better understand indigenous peoples’ perspectives on climate, and also to analyze the heroic methods and strategies used by #noDAPL protesters to make their voices heard. Teaching the role play over a few days to build background knowledge, we wanted students to be able to empathize with the stakeholders in this fight in order to better understand the stakes, and the resources, both natural and financial, at play in this particular issue. Without much other context, we jumped right into the role play. Once all of the DAPL stakeholders were named and their arguments analyzed, we were then able to dig into the context behind each of these positions.

In order for students to understand the ways in which people power with limited resources (as the Standing Rock Sioux exemplified) can strategize and make their voices heard, students needed to investigate the levers of power. So, we introduced our students to an old chestnut of community-based organizing strategy: power mapping.

Using the Midwest Academy framework and the resources from Zinn to provide primary and secondary source support, students power-mapped (and backwards power-mapped) the DAPL fight. They thought about specific targets — or stakeholders they wanted to move — as they designed short-, medium-, and long-term goals to achieve their organizational aims and to move stakeholders.

These frameworks allowed students to explore the roots of grassroots organizing. With with the examples provided by the Standing Rock Sioux and the curricular supports provided by the Zinn Education Project, the power mapping exercise was not just theoretical for my students, but was a case of real stakes and the struggle for climate justice.

I have used pieces from a variety of the Zinn Education Project’s climate justice lessons in order to incorporate them into a larger, comprehensive unit on the subject. To introduce my climate justice unit, we read the testimonials from the lesson Don’t Take Our Voices Away. It was a perfect way to put human faces to the struggle for climate justice, which is often lacking in climate studies in general, and it was also a good, relevant way to incorporate indigenous voices into a lesson.

As a culminating project, one of my high school students has shown interest in actually teaching The (Young) People’s Climate Conference to an elementary classroom in our district. I think taking on this role will further cement the lessons of climate justice within her.

I recently used the Climate Crisis Trial in my Economics of Social Issues class. The trial setting, in which students had to defend themselves against criminal accusations, made this activity highly engaging. It also points out the complexity of the climate change problem: all of the defendants in the activity are guilty to some degree. I assigned the role of prosecutor to a student who is involved in mock trial and he did an amazing job. I will definitely use this activity again.

I use the lesson, Meet Today’s Climate Justice Activists: A mixer on the people saving the world as part of my unit on climate change. In my unit, we asked “what is justice” and what it means in regard to climate change. One of the goals of our school is for our students to “take action,” so this lesson gives them role models on how to take action in regard to climate change.

I used it with three of my classes, 125 students total. The students responded well to playing roles including Eve Miller, Harry Smiskin, Victoria Barrett, AOC, Kathy Jetnil-Kijner, Mishka Banuri, Linda Garcia, Hannah Jones, Simmone Ahiaku, Henry Red Cloud, Joanna Sustento, Lucie Atkin-Bolton, Greta Thunberg, Arturo Massol-Deya, Xiuhtezcatl Martinez.

The directions in the lesson were helpful in making the time productive, and I liked the concept of a mixer as the setting for the lesson. At my school, we use a variety of strategies from “The Strategic Teacher” and SRI, but I have never used a mixer before. It was a nice variation that added novelty to the lesson structure, and the students responded well to it.

I used the Zinn Education Project’s Climate Change Mixer in a problem-solving project with my 8th grade science students, where I had students work in teams to create an essential question around one of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Then, they had to propose a solution to address their question. They needed to be able to identify various stakeholders and whose interest was being served by their solution.

Once students had their questions, my school’s librarian and I collaborated to have the students engage in the Climate Change Mixer. The different experiences and perspectives of the individuals represented in the mixer activity really resonated with the students. They were highly engaged during the activity, and were able to identify new insights that they gained from their conversations while in the roles.

When they returned to the sustainability questions, the mixer activity helped students identify who is, and who is not, being considered and impacted in their projects’ solutions.

Pulling from A People’s Curriculum for the Earth, my class has used the reading “Plastics and Poverty” by Van Jones as well as the Climate Change Mixer in two, semester-long interdisciplinary learning expeditions.

Our first expedition circled around the ideas “power and privilege,” where we looked at Oregon’s history of inequities, and how systemic oppression shapes the communities we live in. This lesson plan and the discussion following helped students grasp the connection between harmful products, industry and people experiencing poverty.

Students made a tangible connection to the “Plastics and Poverty” reading when participating in a series of clean ups around our school, where there are several homeless camps tucked into the the trees and vacant lots. The plastic waste in our high desert climate disintegrates rather rapidly, and breaks down into the soil at a level where it can be hard to even remove it. Seeing all of this plasticizing of our soils, and human suffering directly out our door caused these students to make a shift in our curriculum as they saw the need to study both homelessness, and pollution in a greater depth in order to support the people in need in our community.

Our learning expedition culminated in an evening of fundraising, cold weather clothing donations, and presentations about systems of inequity in Oregon, and the leaders of change that are making a difference.

There are few lessons that I enjoy teaching more than ‘Don’t Take Our Voices Away’: A Role Play on the Indigenous Peoples’ Global Summit on Climate Change in my science classroom. In part, because it gives tangible details and a human face to the issue, not just a story of polar bears or talk about temperature. This is missing in a lot of the science curriculum we are provided. Likewise, the voice of indigenous people in the world is something quite absent in our westernized science curriculum, which is maybe not surprising because these voices are also being left out of world decisions. Those points are what drew me to teaching the lesson. I keep teaching it because of how my students respond. They enjoy the structure of the activity, that they have some agency and control in what happens, as they get to take on the roles and make proposals.

Thank you, to the Zinn Education Project, for providing such a contemporary and fun resource in the Climate Crisis Mixer lesson! My students loved taking on all the various personas.

When I told my 8th grade social studies students that we would be exploring climate change, I didn’t receive the most receptive, encouraging responses. They made comments to the effect of, “We just studied this in science, why are we learning about this in social studies?”

A revealing question, one that exposes how compartmentalized and disconnected they saw this issue from society. Before this semester, having never delved into climate change as a social studies educator, I would have been at loss. Then, I turned to A People’s Curriculum for the Earth. The collection of primary-source based lessons and activities embedded in this book proved to be an invaluable and powerful resource.

Lessons like the Climate Change Mixer, Paradise Lost, and the Thingamabob simulation took my students from a place of what appeared to be indifference and complacency, to a place of inquiry, compassion, and activism.

The culminating activity involved having my students participate in a mock trial based on Bill Bigelow’s role play activity ‘Who’s to Blame for the Climate Crisis’? By this point of our study, my students were emotionally and intellectually ‘invested’ and were genuinely curious as to what or who is responsible for the environmental crisis.

A People’s Curriculum for the Earth prompted me as an educator to teach differently — more holistically, and more critically. It also reminded me of the importance of cultivating the learning conditions for students to make those intimate connections between themselves, other human beings, and the earth.

I used the Meet Today’s Climate Justice Activists in my classroom and it helped my students better understand the variety of people who are engaged in climate justice work.

First, I instructed my students to conduct research on their given activist (I used all United States-based people, as this was for a U.S. History class) and come to class with information beyond that on the blurb. Then, I asked them to make an infographic about their person to use as a prop in the mixer. Later, I hung it up in the dining hall for the whole school community to see.

It was great for them to see young people like themselves taking action around the country. The words and actions of their activists stayed with them.

I recommend Standing with Standing Rock: A Role Play on the Dakota Access Pipeline, whether it be for teaching current issues Native communities face and/or building empathy and the importance of considering multiple perspectives.

While I don’t love many role playing lessons I’ve witnessed, I found this one to be effective and created with thoughtfulness. As a Native educator, I found that not only did this lesson seem valuable for a group of students, but I actually took away a lot for myself. As someone who views pipelines as very real threats to my communities and wholeheartedly supports pipeline opposition efforts, it was powerful for me to try on the perspective of a pipeline worker for this activity. I still strongly oppose pipelines, but this lesson forced me to humanize another side of this complex issue, to see the workers as people with not vastly different needs than mine and my family’s.

I will say that if you have Native students in your class, please be mindful of how this experience could be triggering for them, particularly with one of the media sources used in the beginning of the lesson of DAPL workers setting dogs on the water protectors. I found this to be emotional and hard to watch in the presence of others.

I had my high school social studies class first watch and read “Tell Them” by Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner. This poem is one of several Jetnil-Kijner poems recommended in the article, Climate Change, Gender, and Nuclear Bombs. Then, we watched the Josh Fox film, How To Let Go Of The World And Love All The Things That Climate Can’t Change (2016). After absorbing the art and messages, students chose imagery and quotes from the poem and the film to guide their research about other places and people on the frontlines of climate change. Finally, they used what they found in their research to compose their own “Tell Them” style poem.

(The lesson Teaching to the Heart: Poetry, Climate Change, and Sacred Spaces describes how another teacher used Jetnil-Kijiner’s work in her own curriculum.)

This activity was midway through our Modern World History / English Language Arts collaborative Climate Justice Unit. Students shared their poems in a read-around in History class. Poems were on display (and loosely “mapped” across a wall) for visitors to read during our unit final, which was a Climate Justice Symposium. During the symposium, Students presented TED style speeches about climate justice for their English class, and for social studies, students shared original lesson plans for incorporating climate justice into a variety of content areas and grade levels.

I use documentaries pretty strategically, often to lift up POC narratives I can’t provide, and my students know that if I show them a film, I must be pretty passionate about both the message and the visual I’m presenting. I really like showing documentaries in their entirety, respecting the narrative arc created by the writers and directors, even if we must watch them over the course of a few days in order to better break them down and fit them into our public school schedule.

That said, I almost skipped over a segment near the end of the film This Changes Everything, where Naomi Klein is at the Heartland Thinktank climate conference, thinking my students might find this section less exciting and hard to grasp.

At the last minute, I decided to keep it in. I stopped the film, explaining to my kids what they were witnessing, as it was a bit confusing for them.

To do this, I posed the question: who would not benefit or get on board with slowing/ending climate change?

Having experienced the Stories from the Climate Crisis Mixer helped them delve into this question. Students named Chris, the apple farmer, Richard, Delta’s CEO, and Roman, the oil businessman from the mixer, citing that “rich businessmen” and “people who make money from other people hurting” or people who have enough money to “live where they want” would want climate change to keep happening. Another student talked about how “if you sell nonrenewable resources then you wouldn’t want people to believe climate change because you might go out of business.” From that place, we were able to talk about who might attend such a conference and why this conference was taking place, before continuing with the segment.

At the end of that clip, the person they are interviewing in the film says “If you want more trees, use more wood, because using more wood sends a signal to the marketplace that trees have value. If you want more elephants, market their ivory.”

Though the kids had reacted to many stories in the movie, this was the first point they were outraged; literally yelling at the screen in disbelief: “That’s ridiculous!” “That makes no sense!” “He’s wrong!” “You can’t kill the elephants” with a few more intense and explicit comments mixed in.

It was kinda amazing. I paused at this point for discussion. This scene helped my middle schoolers push deeper into their understanding of capitalism, maybe more than any other approach yet. Though the Thingamabob Game helped, too, it was hard for them to grasp until this point. I asked them what felt wrong about his argument.

“Companies selling things, ultimately want to sell them, they don’t always care about those things. Selling more doesn’t guarantee their will be more,” shared Sophie.

Leo G. chimed in and added “It’s usually the opposite because protecting the environment or changing how we do things would cost money.” Daniya then summed up their points: “Sometimes making money gets in the way of everything else.”

We started the movie back up to finish it, and in the very next scene, Naomi says, “And here’s the truly weird thing about Heartland, I actually think they’re right.” Without waiting for the dramatic pause to end, students were yelling at the screen again, but once we resumed, they could hear the next line “not about the elephants, not about the science denial, but something more basic… that if climate change is taken seriously than it changes everything,” at which finally students were able to sigh in relief and finish the film, cheering at the end.

Having read the book by the same name, I was excited to have both this film as well as Naomi Klein’s article Why #BlackLivesMatter Should Transform the Climate Debate to share with students the invaluable information Klein is presenting, in formats that middle school students could interact with. They helped push our study of climate change in science class to one that doesn’t ignore the connections to race and capitalism.

As a teacher educator, I use the Climate Change mixer and the Young People’s Conference on Climate Change in order to support my students’ understanding of how colonialism, globalization, and climate change intersect today. The activities help my students, who are pre-service teachers, to connect science to social studies in meaningful ways and to teach in interdisciplinary and critical ways.

We often build on the two lessons by developing a TourBuilder narrative to emphasize narrative and geography, and have also included PBS’s interactive “The Last Generation.” This site provides a face to people like those under discussion in the Climate Change Mixer and also steps us into discussions of climate change displacement and immigration as well as other economic/political consequences that may seem unrelated.

Having access to these resources has been beneficial in a lot of ways and has greatly enhanced our teaching and learning in relation to climate change.

I love the Zinn Education Project’s resources. I teach environmental science and biology. These resources are imperative for fostering critical reflection and interrogation in us all about environmental issues and how they adversely affect some more than others, particularly racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically minoritized people in our Buffalo community.

I have used the article, “The Big Red Dot of Environmental Racism” by Alma Anderson McDonald as an introduction to environmental science and to situate our course’s attention to environmental justice. Students are familiar with the term, racism, mostly from an interpersonal standpoint. However, we begin to unpack racism in structural, institutional terms.

We take our discussion of racism further by exploring environmental racism, which this article helps make more concrete. Students often have not heard of environmental racism prior to this lesson. Students share places they love — their house, mountains in another state which they have visited, the beach, a local park, etc. This activity serves as an icebreaker as we get to learn more about each other.

McDonald’s article is accessible and full of imagery; overall, students enjoy reading it. While students initially do not consider our community as toxic as Hattiesburg, after discussion and exploration of local data — from pollutant concentrations and GIS — they begin to recognize that certain portions of our community are more adversely impacted. They ponder medical ailments, from asthma to cancer and their frequencies.

Students are amazed at how much they have not learned about their local environment and ways it has been environmentally degraded over the years. This lesson serves as an excellent branching off point for further exploration throughout the course.

Who’s to blame for causing the climate crisis? Ss explore this ? in an experiential role playing activity from @ZinnEdProject called “The Climate Crisis Trial.” Five “defendants” are on trial for the role each played in causing climate change. High-level engagement and thinking! pic.twitter.com/Wuy1bVG5v3

— Brett Benson (@MrBensonNMS) May 3, 2022

Workshop Stories

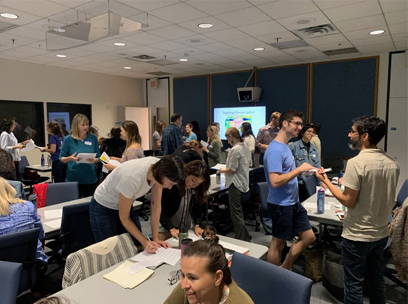

An “all day workshop” can make me pretty skeptical. But when Bill Bigelow, one of my biggest inspirations and mentors as an educator, came to town on the first weekend in December, I excitedly hopped out of bed and geared up for a day of thinking about and strategizing how to keep teaching climate justice.

The depth of Bill’s content knowledge and his years of teaching experience allowed him to answer our questions with meaningful insights and model how to work with students. And his interest and discipline related to study reminded me to be learning just as much as I am teaching — to be in the scholarship about climate justice, and to bring the global context of it into my classroom.

Already an avid user of the A People’s Curriculum for the Earth, I was also thrilled to experience several of the exercises with other participants at the workshop. I have understood the reasons behind using the Climate Change Mixer, the Vía Campesina summit, and the Write That I poems. But the goals of teaching this way took on a whole new level of relevance; I felt why it matters to approach this type of knowledge in such a student-centered way.

We have got to call our students into the creative, community-building that we’ll all need to resist inequity and injustice.

In December 2019, the Spark Teacher Education Institute attended Bill Bigelow’s Climate Justice Workshop in Brattleboro, Vermont. We were able to engage in critical climate justice pedagogy alongside teachers and community organizers from Vermont, Massachusetts and New Hampshire.

It was amazing to be there with so many other teacher activists who are educating students in order to take action against the capitalist-driven climate crisis. I thought the activities, such as the Climate Justice Mixer and La Via Campesina Roleplay, were incredible in how they highlighted the stories of people and movements in the resistance. Many of the teachers already have plans to incorporate these activities in their classrooms.

Thanks again to Bigelow for sharing his experience and knowledge along with many others who are helping to make this world a more just and healthy place!

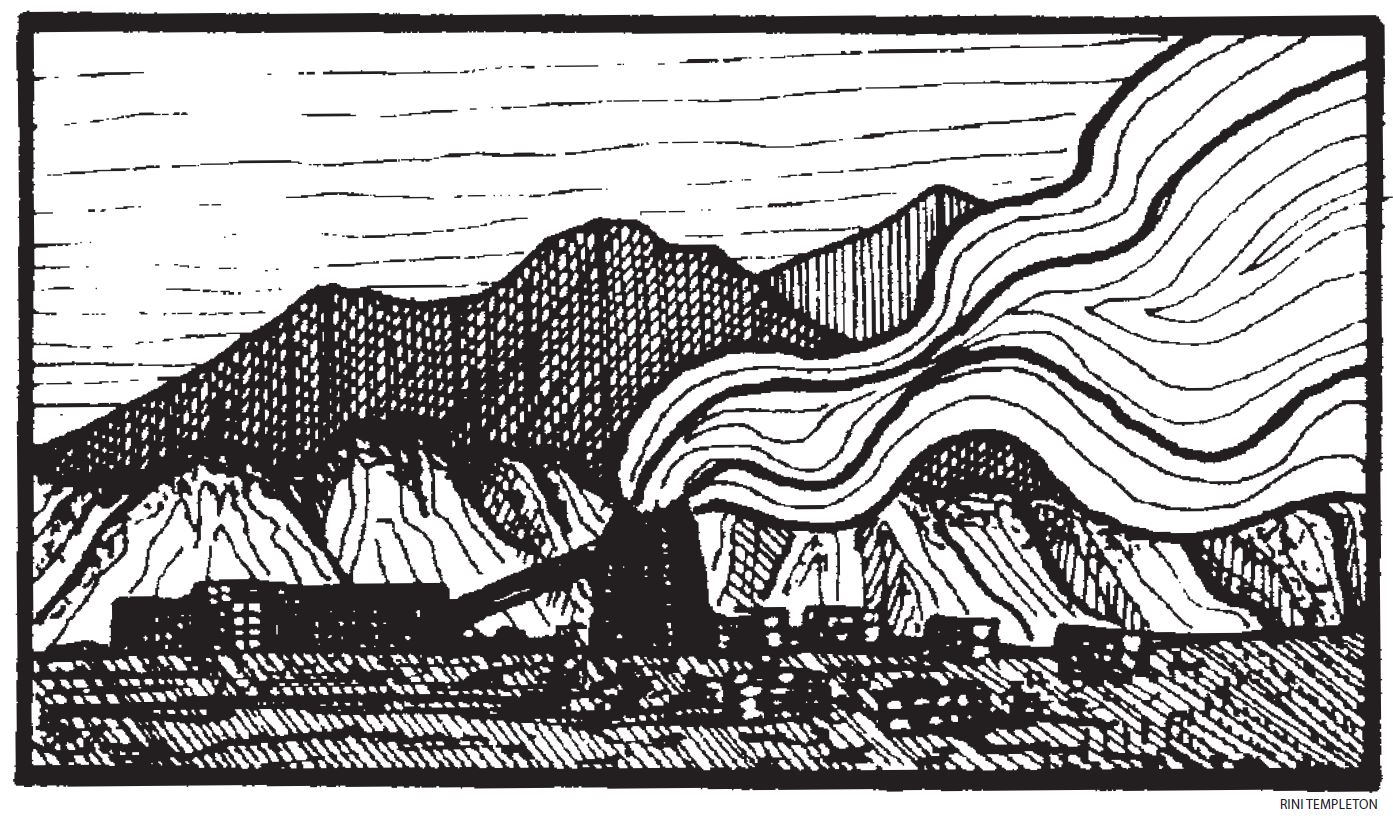

This collection is part of our Teach Climate Justice Campaign, which offers lessons that can be used in social studies, language arts, science, and other subjects. Many of the lessons described below come from A People’s Curriculum for the Earth: Teaching Climate Change and the Environmental Crisis, a teaching guide published by Rethinking Schools.

Submit a short narrative about teaching with one of the Zinn Education Project’s climate justice lessons or downloadable articles and you will receive three free books abut environmental justice and climate change.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn