Schools call for climate justice and student activism

By Bill Bigelow

In what may be a first in the nation, this week the Portland, Oregon school board passed a sweeping “climate justice” resolution that commits the school district to “abandon the use of any adopted text material that is found to express doubt about the severity of the climate crisis or its roots in human activity.” The resolution further commits the school district to develop a plan to “address climate change and climate justice in all Portland Public Schools.”

The resolution is the product of a months-long effort by teachers, parents, students, and climate justice activists to press the Portland school district to make “climate literacy” a priority. It grew out of a November gathering of teachers and climate activists sponsored by 350PDX, Portland’s affiliate of the climate justice organization, 350.org. The group’s resolution was endorsed by more than 30 community organizations. Portland’s Board of Education approved it unanimously late Tuesday evening, cheered by dozens of teachers, students, and activists from 350PDX, the Raging Grannies, Rising Tide, the Sierra Club, Oregon Physicians for Social Responsibility, Climate Jobs PDX, and a host of other groups.

“All Portland Public Schools students should develop confidence and passion when it comes to making a positive difference in society, and come to see themselves as activists and leaders for social and environmental justice—especially through seeing the diversity of people around the world who are fighting the root causes of climate change.”

Some of the activists involved in getting the climate resolution passed. Image: createplenty.org.

The resolution’s “recitals”—its guiding principles—address the characteristics that the Portland school district seeks to nurture in its students: “All Portland Public Schools students should develop confidence and passion when it comes to making a positive difference in society, and come to see themselves as activists and leaders for social and environmental justice—especially through seeing the diversity of people around the world who are fighting the root causes of climate change; and it is vital that students reflect on local impacts of the climate crisis, and recognize how their own communities and lives are implicated…”

Portland’s resolution also calls for training in green jobs, and notes that “as our society moves rapidly and definitively away from fossil fuels, we will need to prepare our students for robust job opportunities in green technologies, construction, and restoration efforts…”

The school district’s commitment to rid itself of text materials that encourage students to doubt the severity of the climate crisis or its roots in human activity was prompted by the school district’s long use of materials that do just that. One textbook still in use in Portland schools is Physical Science: Concepts in Action, which informs high school students that “Carbon dioxide emissions from motor vehicles, power plants, and other sources may contribute to global warming”—implying that motor vehicles and power plants may not contribute to global warming. The book’s brief section on climate change consistently uses may and might and could to sow doubt about the severity and human causes of climate change.

Another text used with almost all Portland high school students is Holt McDougal’s Modern World History, which includes a scant three paragraphs on climate change, the second of which begins: “Not all scientists agree with the theory of the greenhouse effect.” Presumably, Portland’s new policy will require that these texts be abandoned.

Rather than asking for the adoption of new textbooks, Portland’s resolution imagines a collective process to create and disseminate new materials: The school district will commit itself “to providing teachers, administrators, and other school personnel with professional development, curricular materials, and outdoor and field studies that explore the breadth of causes and consequences of the climate crisis as well as potential solutions that address the root causes of the crisis; and do so in ways that are participatory, imaginative, and respectful of students’ and teachers’ creativity and eagerness to be part of addressing global problems, and that build a sense of personal efficacy and empowerment…”

Portland’s resolution also acknowledges that this curriculum development will not come from education corporations, but needs to be a grassroots process, “drawing on local resources to build climate justice curriculum—especially inviting the participation of people from ‘frontline’ communities, which have been the first and hardest hit by climate change—and people who are here, in part, as climate refugees…”

In their testimony in support of the climate justice resolution, a number of activists mentioned how they were inspired by their participation in the recent “Break Free” demonstrations at the Shell and Tesoro oil refineries in Anacortes, Washington. High school student Gabrielle Lemieux told the school board, “We put our bodies on the line by risking arrest with protests and even a blockade of the railroad tracks leading to two major oil refineries.

Cheryl Lohrmann and Gaby Lemieux testifying before the school board. Image: createplenty.org.

“I am 17 years old. While I was there, I was asked several times why at my age, I felt it was necessary to risk arrest by standing with other activists. People said to me, ‘You have a whole lifetime ahead of you to get arrested, to do this kind of work.’

“My response is: We don’t have my lifetime to wait. We don’t even have the couple years it will be before I’m truly an adult. My action starts now, or it works never.”

The school board did not accept all components of the resolution introduced by climate justice activists. One plank called on the school district not “to engage in any partnerships with fossil fuel companies, which offer legitimacy to these companies”—targeting Chevron’s Donors Choose program. Another plank in the activists’ version of the climate justice resolution—which the school board omitted—asked the school district to express solidarity with the recent Portland City Council measure opposing “expansion of infrastructure whose primary purpose is transporting or storing fossil fuels in or through Portland or adjacent waterways.”

Still, climate justice resolution organizers and their many supporters who attended this week’s school board meeting were jubilant after the board’s unanimous vote. The vote was greeted with tears, hugs, high fives, and a standing ovation.

As Lincoln High School teacher Tim Swinehart commented after the vote. “Now the real work begins: transforming the principles of this resolution into the education of climate literate students across the district who feel empowered to work toward a more just and sustainable future.”

Read the full text of the Climate Justice resolution here (pdf).

________________________________________

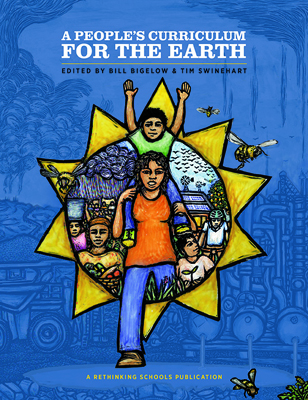

Bill Bigelow (bill@rethinkingschools.org) taught high school social studies in Portland schools for many years and co-edited A People’s Curriculum for the Earth: Teaching Climate Change and the Environmental Crisis. He is curriculum editor of Rethinking Schools magazine and is a member of the collective that introduced the climate justice resolution to the Portland school board.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn