I didn’t realize coming in to this that the author of A More Beautiful and Terrible History would be presenting and I got so excited when I did! Her book was my inspiration to take a hard look at how my lessons were framed this year and make a change.

I learned a lot. The length of the session was perfect. We scratched the surface but also dove deep with resources to continue learning and growing. This Zoom with over 200 participants was way more productive than Zooms I’ve been on with 10 or less people. KUDOS to the team!

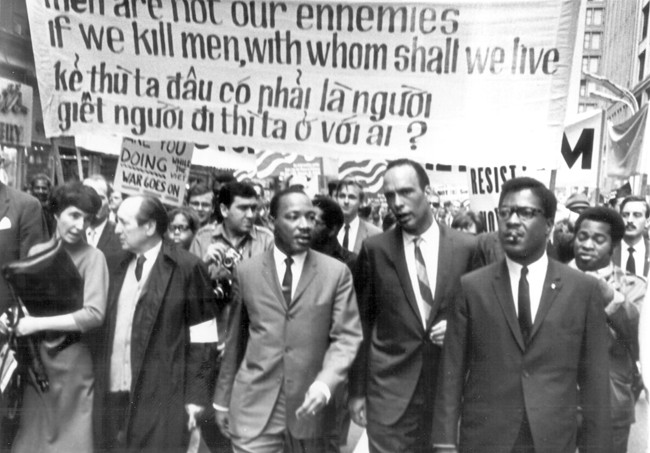

On International Workers’ Day (May 1), close to 300 educators, parents, and students joined the session with Jeanne Theoharis and Jesse Hagopian on the radical history of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

On International Workers’ Day (May 1), close to 300 educators, parents, and students joined the session with Jeanne Theoharis and Jesse Hagopian on the radical history of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

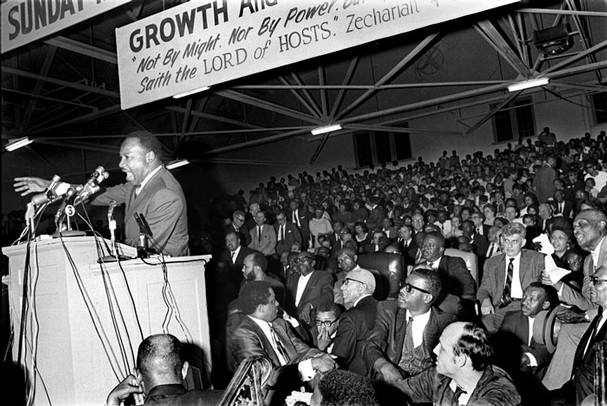

This sixth session in the Zinn Education Project People’s Historians Online series addressed King’s positions on oppression in the North, police brutality, the Memphis sanitation workers, reparations (the “bad check”), the Poor People’s Campaign, and more. Theoharis also talked about the radical influence of Coretta Scott King, which generated a lot of interest in the chat box and session reflections.

Highlights

Hagopian opened the conversation by noting,

In some ways Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is as close to a saint as we have in this country. In A More Beautiful and Terrible History you write, “When asked to name a ‘most famous American’ other than a president ‘from Columbus to today,’ high school students most often chose Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks.”

In some ways Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is as close to a saint as we have in this country. In A More Beautiful and Terrible History you write, “When asked to name a ‘most famous American’ other than a president ‘from Columbus to today,’ high school students most often chose Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks.”

Theoharis responded that while he was alive, King did not enjoy popular support. In fact, 75% of Americans did not approve of King’s actions and the U.S. government and corporate media actively tried to undermine him. Since his assasination, a fable has been created about King that makes him a safe, convenient hero as Carl Wendell Hines Jr. writes in his poem A Dead Man’s Dream,

Dead men make such convenient heroes.

For they cannot rise to challenge the images

That we might fashion from their lives.

It is easier to build monuments

Than to build a better world.

Participant Sashray McCormack shared two of the polls conducted during the session as evidence of “how much our history has been sanitized and whitewashed” and therefore how important these sessions are to correct the narrative in classrooms.

This is why resources like the @ZinnEdProject are important… pic.twitter.com/lMm6e8iF44

— Shashray McCormack (@InspireShashray) May 1, 2020

Theoharis responded to a question about King’s position on public health by pointing to his statement at an annual meeting of the Medical Committee for Human Rights in Chicago in March of 1966. A participant posted an excerpt from that speech in the chat box, as reported by the Asssociated Press.

We are concerned about the constant use of federal funds to support this most notorious expression of segregation. Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health is the most shocking and the most inhuman because it often results in physical death. I see no alternative to direct action and creative nonviolence to raise the conscience of the nation.

Video

Here is a video of the full session (except the breakout groups.)

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: I want to welcome you all here on behalf of the Zinn Education Project for our session on rethinking Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the King you never learned in school. I want to start off by wishing everybody a happy International Workers’ Day, everybody. I’m really happy today to be in conversation with the great people’s historian Jeanne Theoharis on this International Workers’ Day.

I want to start with looking at Martin Luther King today. I think in some ways, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is really as close to a saint as we have in this country. You write in A More Beautiful and Terrible History, quote, “When asked to name a most famous American other than a president, from Columbus to today, high school students most often choose Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks. But I think with this sanctification has also come a sanitization of his message.” I think everybody today celebrates Martin Luther King, Jr. There was a RAM commercial recently that used his major anticapitalist speech to sell trucks. McDonalds has used his image to celebrate him, and then they go on paying unlivable wages to mostly Black and Brown workers. So, I guess my question is, why is King so widely celebrated today? Because it’s really in contrast to the way he was seen in his own day. Certainly the majority of Americans didn’t approve of him, and the American government was downright threatened by him. So talk about that discrepancy.

Theoharis: So, polls in 1966 [showed] about three quarters of Americans don’t approve of King’s tactics. When King was assassinated in 1968, Representative John Conyers immediately introduced a bill to have a national holiday to celebrate Dr. King. It goes nowhere. Nowhere. So we don’t get a federal holiday for Dr. King for 15 years. People struggled for 15 years to try to get a federal holiday for Dr. King and it didn’t happen until 1983. With President Ronald Reagan’s long opposition to a King holiday, his administration began to see supporting the King holiday as being useful to Reagan’s reelection campaign. Basically, King can position Reagan, or support for the King holiday can position Reagan, who’s having a sensitivity problem with moderate white voters, and this is going to help.

Again, his long opposition in terms of support for the holiday and in 1993 the holiday passed. In Reagan’s speech he in some sense previews the kind of narrative — I call it a fable — that we’re going to get. So, it’s basically a celebration of King, a celebration that what King did wouldn’t be possible in most countries, and that we had an injustice and we corrected it. I mean, I’m paraphrasing Reagan, but basically this is what he says. And this is going to be the essence of the fable of Martin Luther King that we now get today and that is now celebrated. We had a problem: good, decent people banded together and we fixed it, and that erases both how opposed, as you just pointed out, King was in his own lifetime. It misses that many of the issues King and his comrades were fighting around are still issues for us today. And it misses all of the people around Dr. King. It sort of traffics in a “great man” view of history. Now, in polls, three quarters of Americans approve of King, love King, and imagine they would have been with King if he was here with us today. But, at the same time, [these same people] criticize contemporary movements in much the same way that they criticized King 50 years ago.

Hagopian: Yeah, that’s right. That’s absolutely right. It’s amazing to see people who would have despised King celebrating him every year. I mean, President Trump trumpets King’s legacy even. It’s really breathtaking the way his image has been used today. I think one important aspect of Dr. King’s politics that rarely gets taught in school, or discussed in corporate textbooks, was his consistent critique of Northern liberalism. So, I’m hoping you can talk not just about King’s challenge of southern Jim Crow segregation, but also his analysis of this and his struggle against institutional racism in the north.

Theoharis: I think the story we get in textbooks is we have King and we get to the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Then mysteriously weeks later we have the Watts riot and King is surprised by this. Then we have Black Power and the backlash. That’s the narrative that we get in standard textbooks. It’s seen as King discovering the North after Watts. But, if we actually look at what Dr. King is doing and what he is talking about in those years before Watts, he is very clear that segregation and racism and systemic racism are national problems, not just southern problems. He is consistently calling out northern liberals for being willing to support the movement in the south but not being willing to look at their own cities, at their own practices.

This really starts with the beginning of the SCLC in 1957. As a national leader of the SCLC, Dr. King is not just talking about Southern Jim Crow, he’s talking about Northern Jim Crow. He’s talking directly to Northern liberals and saying, “You can’t just call out,” or 1960, and I quote from him, “there’s a pressing need for a liberalism in the North that is truly liberal, who will not only rise up in indignation when a Negro is lynched in Mississippi, but will be equally incensed when a Negro is denied the right to live in his neighborhood or secure top position in his business.” This is King in 1960 in New York.

I think that almost never do we grapple with this King in school, in part because it calls out a kind of myth that has, I think, grown around the Civil Rights Movement, which is that it was predominantly focused on a southern problem, and that was largely fixed. It becomes this triumphal narrative struggle, and Northern liberals come off as the good guys in that narrative. To really take seriously King saying over and over and over, “We can’t just talk about the South, we have to talk about the North.” We have to remember King as a minister; King is not a politician, he’s not beholden to fundraising. And what you do as a minister is you call out your own, you call out your flock. That’s one of the responsibilities. So, in some sense, it’s not surprising that over and over and over in spaces in the North, he’s saying to Northern liberals look at your own house first.

Hagopian: Absolutely. I appreciate you clarifying that history. Even in some of the radical histories that I’ve studied, I get that same idea, that he didn’t really think about the north until the Watts riot. I tried to correct that in my own school. We have a mural of Martin Luther King up and the kids pass by it every day. I think that most of them think it’s just there because he’s a great leader that we should respect. But it’s really there because he traveled to Seattle one time and gave a speech at Garfield High School, and in that speech he wasn’t just condemning Jim Crow segregation, he was talking about the redlining of the Central District neighborhood that our school is in. He was talking about the lack of jobs in Black and Brown communities. I think that’s such an important legacy to draw out, and I think connected to his views on the north are his views on police brutality. One of the only things students ever hear, I think, from MLK are excerpts from the “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington. I think they rarely even hear the whole speech because if we listen to the whole speech you might hear actually that he condemns police brutality in the speech. So, I’m wondering if you can talk about King’s confrontation with police brutality and also what do you think King would would say about Black Lives Matter today?

Theoharis: If we look at what King was doing in the early 1960s, again, before Watts, he was talking about police brutality at the March on Washington. He’s in LA in the early 1960s multiple times and he’s talking about police brutality. There had been a campaign around police brutality in LA in the early 1960s that really sort of expands after the killing of the Nation of Islam Secretary Ron Stokes in 1962. So, King is in LA and 1963 and he’s talking about police brutality. In 1964, there’s an uprising in Harlem after a police officer killed 15-year-old Jimmy Powell and the mayor invited King to town. King starts talking about a civilian complaint review board and basically New York political leaders are like, “Get out of here.” So, he’s talking about a civilian complaint review board, he’s talking about police brutality, and he’s also talking about the fact that there’s all this concern about southern police brutality, but northern police brutality — and again, I’m going to quote him — “is rationalized, tolerated, and usually denied.” So again, he’s refusing again.

Certainly if we think about the Civil Rights Movement, many of us have those images from 1963 in Birmingham of police dogs attacking children or in Selma on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. We’re familiar with images of southern police brutality as being part of what the Civil Rights Movement was dealing with. But again, King is also reminding us that northern police brutality is just as much of a problem and yet it’s not being seen as a problem. So when we start to think about what King would be saying about Black Lives Matter, both, he is absolutely talking about police brutality and King is talking about the importance of disruption.

In 1964, in New York again, a group called Brooklyn CORE, which was doing all this organizing in Brooklyn around school segregation, around housing segregation, around jobs in the early 1960s, and they’ve gotten very little change. So in 1964, the world’s fairs came to Flushing Meadows and Queens, and Brooklyn CORE decided they’re going to stall cars on the highway leading out to Flushing Meadows, basically to force people to deal with the problem of inequality in this country. As you might imagine, because it’s what’s happening today, both Black and white moderate leaders in the city are horrified and they hate this idea. They tried to get Dr. King to come out against Brooklyn CORE’s plan and he refused. Again, I’m just going to quote from him, he says, “I hear a lot of talk these days about our direct action, talk alienating former friends. I would rather feel they are bringing to the surface laden prejudices that are already there. If our direct action programs alienated our friends, they never were really our friends.” Dr. King in 1964.

Again, here we have King similarly dealing with this opposition to disruptive direct action and basically refusing these “you should do it in a nicer way” kind of calls. The third thing he’s doing and saying is he’s refusing this focus on crime. Again, I quote from him, “When we asked Negros to abide by the law, let us also demand that the white man abide by the law in the ghettos. Day out, he flagrantly violates building codes. His police,” — his police. This is King’ words — “his police make a mockery of the law and he violates laws on equal employment and education and the provisions for civic services.” He’s also refusing the kinds of frames we see today, which are “what about Black crime?” and he’s focusing, as he would put it, “on the greater crimes of white society.” Again, that’s a quote from King.

Hagopian: It just drives me crazy when people chastise Black Lives Matter activists for their direct action, saying you should be more like Martin Luther King. Yes, they should. King got arrested how many times, did how many direct actions? It’s just so ignorant of King’s legacy and history. So thank you for drawing out those lessons, for sure.

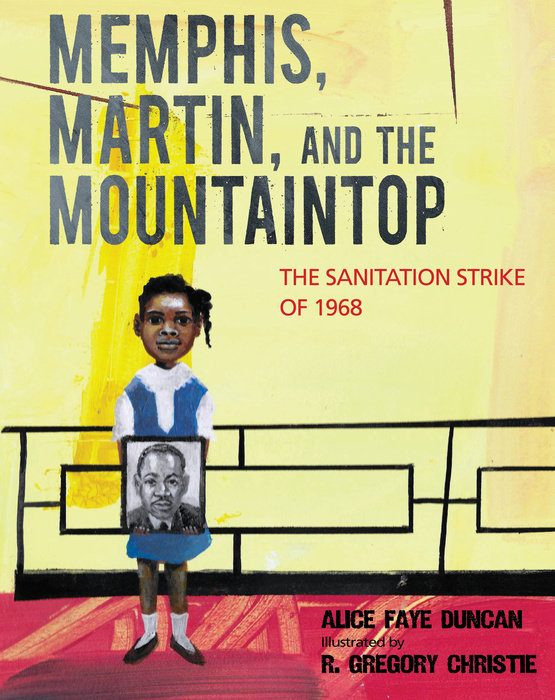

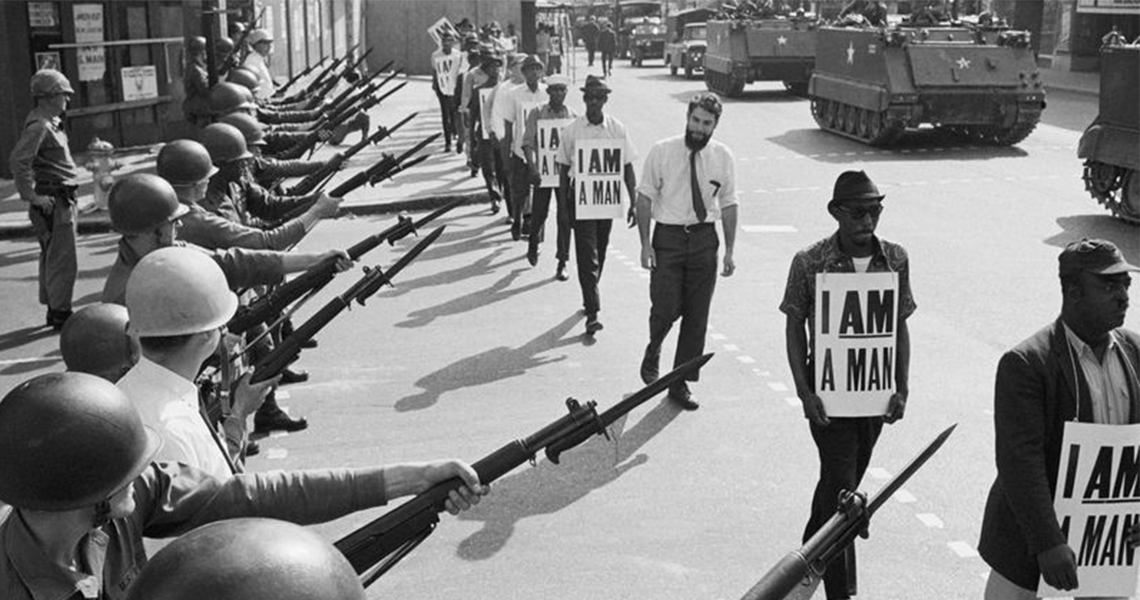

Today is May Day, International Workers Day, a holiday that for a long time vanished from most of America, even though it began here with the historic struggle for the 8 hour day. Then it was brought back to the United States and celebrated more widely after the massive 2006 immigrants’ rights movement just erupted into the streets and brought the tradition back. So I want to talk about King’s last struggle before he was assassinated in Memphis, when he went down to Memphis and brought the Civil Rights Movement with him to support striking Black sanitation workers who were on strike for decent wages. Two of them were killed in the back of a garbage truck and they were thrown out like so much refuse, and their families weren’t supported. I hope you can talk about King’s views on unions, on organizing working people across racial lines for radical change, the Poor People’s Campaign, his views on our economic system and capitalism.

Theoharis: The last campaign he’s building, and this is even before we get to Memphis, is that he is building the Poor People’s Campaign. He decides to do this in Mississippi. He visited a Head Start center in 1966, and he saw these little tiny kids and they’re super excited about lunch. There are four of them, and lunch consists of an apple cut four ways, and you almost never hear people talking about King crying, but he just burst into tears. Apparently he told Ralph Abernathy, “People don’t realize that kids are starving in America.” So, the idea is partly that poverty is kept out of sight.

The second idea is that racism is used to divide poor people and to have poor people see each other as the problem. The idea behind the Poor People’s Campaign is to build a multiracial movement of poor people to come to D.C. and engage in massive civil disobedience so that people are forced to see and deal with issues of poverty and racism. They’re building that in the spring of 1968, and they’re bringing together Chicano organizers, Native American organizers, white organizers, a variety of Black organizers. He’s very much focusing — similar to what we see the Black Panther Party focusing on in the late 1960s — on what we might call the first rainbow coalition, or an original rainbow coalition, which is bringing poor people of different races together. But again, that’s not the way we often teach King.

Then he is asked to come to Memphis because Memphis sanitation workers are striking. Similar to what they’re hoping to do with the Poor People’s Campaign, King is asked to come to Memphis precisely because oftentimes union battles, particularly of workers like sanitation workers, are just kept out of sight. And bringing King will shine a light on this issue. Like you said, it’s not just about wages, it’s about working conditions. That’s where he is when he’s killed. We see Coretta Scott King continue that work, but in the midst of her grief she comes down to Memphis to lead another march to draw attention to — the kind of strength that takes to keep the attention on what’s been done — this strike happening in Memphis. Then she continues the work of the Poor People’s Campaign in May and June of 1968, and that comes to the Capitol, where they built Resurrection City. Again, as with Black Lives Matter, there’s all these criticisms of the Poor People’s Campaign as being vague and not having specific plans. But, in fact, they laid out a very specific set of ideas and things that need to be changed. Similarly, we see the same kinds of [things now] — “You’re not really defining what needs to change,” “You’re too rowdy,” and the same kinds of criticisms in 1968 as we see with Black Lives Matter today.

Hagopian: Absolutely. Such an important correction to the King that we get, that’s just so trapped in only talking about removing signs that say Black and white in the south and not linking it to the broader economic struggles in this country. I think this is such an important correction to that. You also mentioned the bravery of Coretta Scott King in your comments. I wanted to ask you about Martin Luther King’s lifelong partner, Coretta Scott King, who often gets left out of the telling of his story and of the Civil Rights Movement in general. As you write in A More Beautiful and Terrible History, quote, “Coretta Scott King is not just Martin’s quote help mate, but a lifelong economic justice and peace activist pushing her husband’s activism in those directions. So, can you talk about her contribution to the struggle?

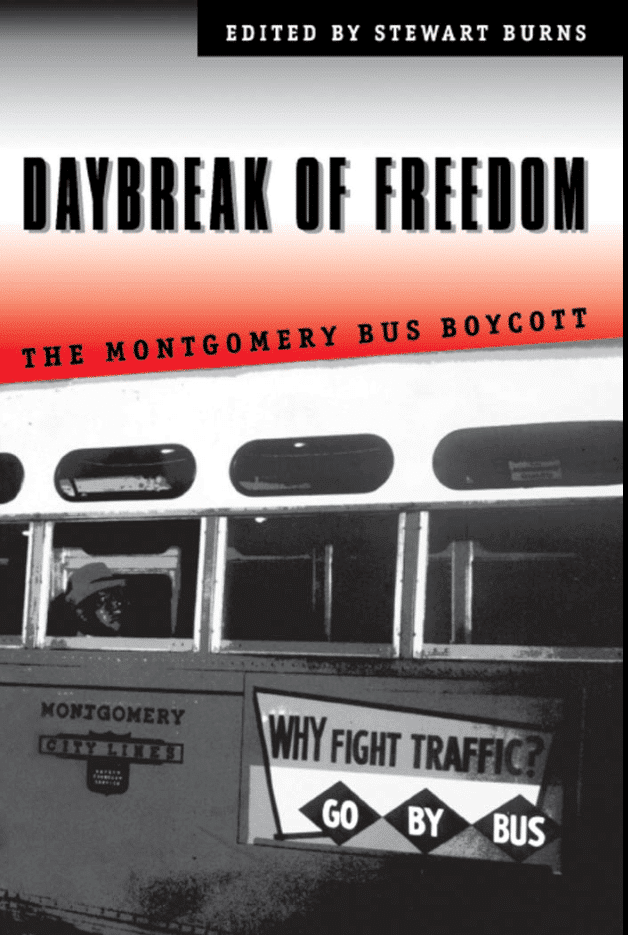

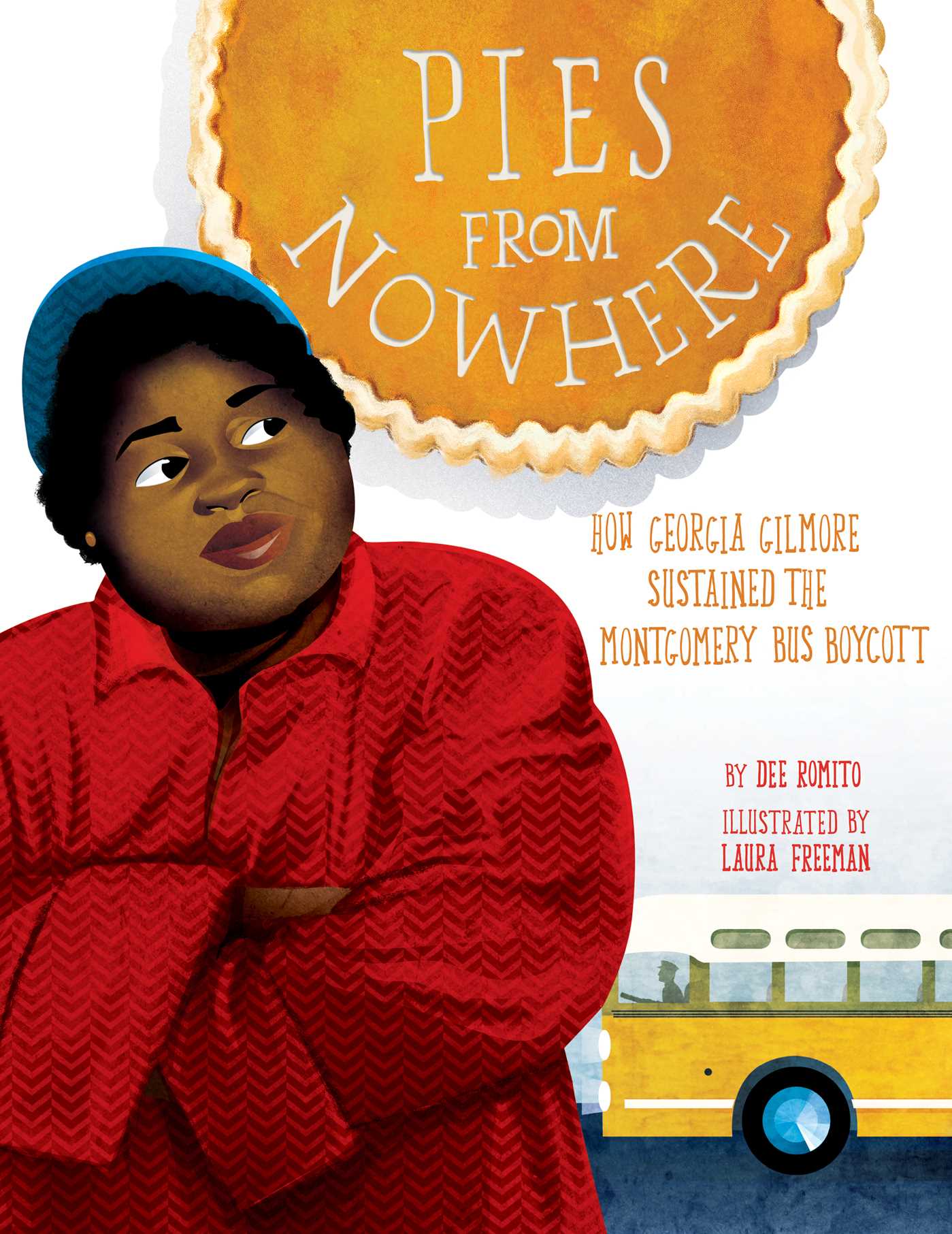

Theoharis: I would love to. One moment that I think often goes unmarked, and because I like to talk about the Montgomery Bus Boycott at any chance I can, happened six weeks into the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Just to remember, the King’s have their first baby, Yolanda, three weeks before Rosa Parks makes her bus stand. So Yolanda is about 10 weeks old when the King’s house is bombed, and Coretta and baby Yolanda are in the house when it’s bombed. They do safely get out of the house, obviously, but it’s terrifying. King comes home and both King’s dad and Coretta’s dad come down to the family. You can imagine, they’re like, “You guys have got to get out of here. And if you won’t go Martin, at least Coretta and the baby should go.” Both dads are united on this. And she is like, “No, we’re not going anywhere.”

I think it’s interesting. Again, King is not King yet. The Montgomery Bus Boycott is not the Montgomery Bus Boycott yet. They’re not even asking for full desegregation on the bus yet. I think if Corretta had decided, and we could imagine why you would decide this, that she and the baby needed to leave Montgomery, the trajectory of the Montgomery Bus Boycott would be very different.

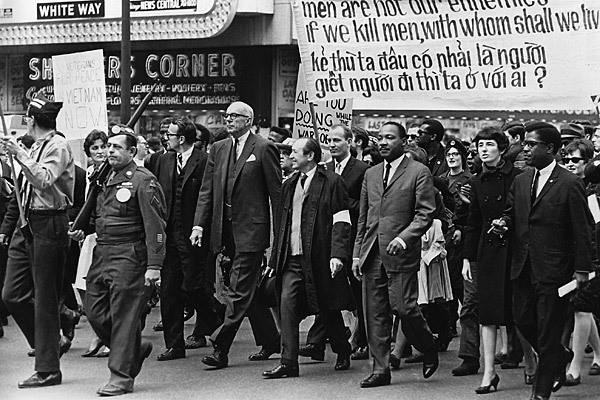

The second thing I think we need to understand is that arguably Corretta is more political and has a wider political understanding than Martin when they meet. That’s particularly around global issues, peace issues. Coretta Scott King had attended the 1948 Progressive Party Convention and supported the third party candidacy of Henry Wallace. Again, this is before she meets Martin and she gets very involved in a global women’s peace movement in the early 1960s. When her husband is awarded the Nobel Prize in 1964, she really sees this as they have a different responsibility to the world now. She begins to work on him that he is going to need to come out against the war in Vietnam. She started speaking out against the war in Vietnam publicly in 1965 and 1966. We cannot understand how we get to King at Riverside Church in April of 1967, without the work of Coretta Scott King laying the groundwork for that speech, because she’s talking about the connections between what’s happening at home in the War on Poverty and what’s happening in the war in Vietnam. She’s talking about global human rights. She’s talking about what it means to be asking Black mothers to send their kids overseas when they are not equal at home. These are ideas that she is talking about already. I think we often imagine that King is somehow like, just in a vacuum or something, when he’s being shaped by many people. But one of the people he’s being shaped by is his wife.

Hagopian: Even before she met him. I mean, that’s such an important corrective to the story. So often Black women get left out of leadership and the political analysis of the Civil War, so I appreciate you bringing that in. King called the United States “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today” and came out against the war in Vietnam. I really didn’t know until you illuminated that for me, that a lot of that impetus came from Coretta Scott King. That’s such a brilliant history. Thank you for sharing that with us.

[breakout rooms]

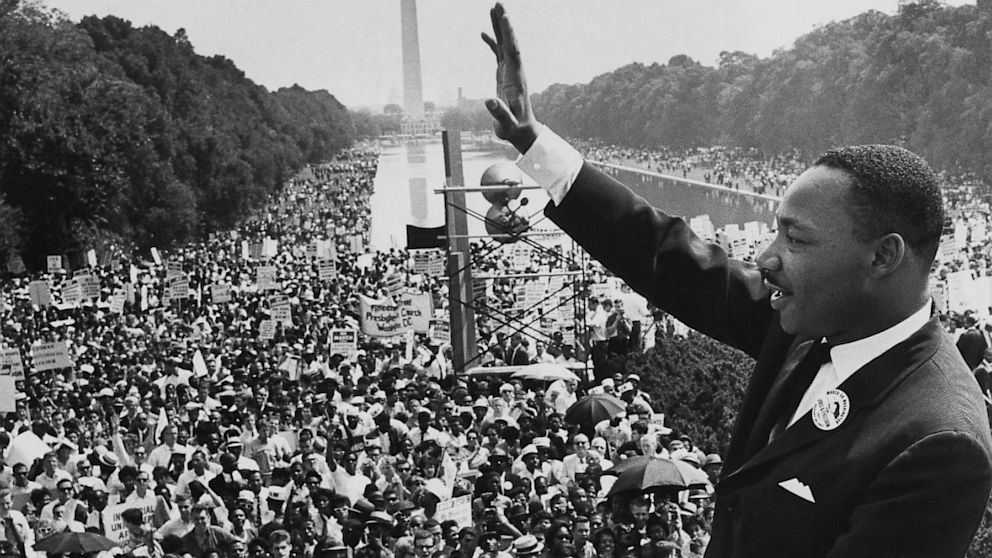

I wanted to go back to the March on Washington because I think it’s misunderstood in many ways. Originally, King’s March on Washington speech was the “Bad Check” speech, not the “I Have a Dream” speech. Jeanne talks about what it means to listen to the whole speech, particularly the beginning, where he talks about how the nation owes Black people a debt and they have come to collect. So Jane, can you talk about the “Bad Check” speech?

Theoharis: I think the first thing to think about when we think about him, starting with this metaphor of Black people having been given a bad check and they’ve come to collect is, again, we don’t use checks. Many of us don’t use checks as much anymore. But, when somebody gives you a bad check, you don’t make it better by saying, “Oh, I’m sorry I gave you a bad check.” You correct a bad check by giving somebody a new good check, a check that [works]. So, we’re talking about material redress. Another word is reparations.

He starts off by talking about this very material debt that the nation owes Black people and that they’ve come to collect, and they believe that the Bank of America is not bankrupt. I think sometimes because King is such a beautiful speaker, we sometimes also miss what’s actually the substance of what he’s actually saying in terms of basically that the country owes Black people a debt.

The other thing I would say about the March on Washington is that we often miss the ways it’s presented today. It seems like it’s the most American event of all time. And that’s not how it’s treated. At the time, in a Gallup poll the week before, most Americans disapprove of it. Many congressmen were speaking out against it, calling it unAmerican. D.C. prepares for it like it’s a foreign army coming, like all the police officers are on duty that day, 150 FBI agents. They closed liquor stores, they canceled all elective surgeries. I mean, they prepare for it like a battle.

The other thing, I think, now we know that the FBI was surveilling Dr. King, but I think the thing to remember is that, in fact, they expanded that surveillance after the March on Washington. They see his influence. I think there’s sometimes this sense that King, in 1963, this is the good, acceptable King. And yet, it is exactly at this moment when the FBI — with Robert Kennedy’s signature, with [John] Kennedy’s approval — decides to bug and wiretap [to] basically listen to his conversations for the rest of his life — his home, his office, his hotel rooms. He gets even more controversial in the last years, and even perhaps more hated by the government. His relationship to Lyndon Johnson gets worse at the end. But I think there’s a way that we paper over how dangerous he is seen in the early 1960s, as well.

Hagopian: Absolutely. We’ve got some good quotes pouring in here. There was just a question that said, “Professor Theoharis, what, if anything, did Dr. King say about public health issues? Was that something he said much about?”

Theoharis: There’s a really good quote; I can’t think of it off the top of my head, but he’s definitely saying health is perhaps one of the most — and he may say one of the most critical if not the most critical kind of issues of justice. Yes, and one of the ways that I’ve seen him talking about health is also, again, as we were talking about at the beginning, around conditions in cities and the ways that those what we might call environmental justice or environmental racism, he’s not using those words, but the conditions that are allowed to persist in slums, in ghettos. He’s calling out all sorts of people. He called out social scientists, he called out northern liberals for refusing to look at the conditions in northern cities. And part of those conditions are what we would call public health issues, as well. There’s a direct quote from King about how crucial health is to justice. Maybe if people know that they can put it in the chat because I’ve seen it, but I can’t do it off the top of my head.

Hagopian: Nice. Thank you for sharing that. It’s so important today as we struggle for justice during the COVID-19 crisis, and especially as we see the dramatic racial disparities in the spread of the disease, that we are armed with King’s belief in everyone having the right to healthcare. There are some more great questions coming in. There’s a question that says, “Professor, I would like to hear more about King and the contemporary Black women organizers like Ella Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer, and Septima Clark, who was deemed the mother of the Civil Rights Movement.

Theoharis: I saw some questions about his views on gender and sexuality and I think one of the things is, King had a ways to go. I think we’re remembering, in some ways, that King comes to public leadership at the age of 26 and is assassinated at the age of 39. One of the things that I admire so much about him — and I think similar to Malcolm, because Malcolm was also assassinated at 39 — is how they’re growing and changing. Certainly on issues of gender and sexuality, he had a ways to go. And that’s true in terms of his ideas about Coretta Scott King, and he believed her role was also to be raising children. So, while he wants her to be his life partner in part because of her politics, he still has these ideas and she’s pushing against that while he’s alive, and wanting a bigger role, wanting a more extensive role.

With Ella Baker and Septima Clark, we see both of them criticizing the ways that he isn’t always recognizing the leadership of women. We see them criticizing the charismatic leadership that he favors coming out of the church. In some ways King is really different from his dad and his dad’s generation in terms of how he’s conceptualizing what his role and responsibility is, but in other ways the ideas of charismatic leadership are very much still part of how he comes into things. So, we see people like Ella Baker and Septima Clark criticizing him for that, just having to lead all that. Like I said, she would tell him not to lead everything, to lead all the marches. So, the women around King are also questioning him.

Hagopian: Important and also to note is that Coretta Scott King came out in favor of same sex marriage when the struggle really blew up, and I think that legacy is important to remember as well. There’s another question about the Poor People’s Campaign. Can you talk about the discord between SCLC and Dr. King over his decision to initiate the Poor People’s Campaign?

Theoharis: At a number of junctures, King is pulling the SCLC with him. In 1966, they made the decision to do a campaign in Chicago with the Poor People’s Campaign. So, there are definitely people, even with the decision to come out publicly [against] Vietnam, there are people in the SCLC and King’s circle who are pushing against this, who don’t see this direction as the right direction. I think that’s another thing we often paper over, and it’s really important to talk with students about is that people are constantly debating and are not on the same page about the right way forward. It’s not just that we have that issue today that people have very different ideas about the right way forward. This is also something happening in SCLC, between SCLC and SNCC.

Also, in terms of the Poor People’s Campaign, one of the issues that King is being called out on — but it’s moving on, in part, also because Coretta Scott King is more there — are issues around welfare, the right to public assistance, the need to both listen to women on welfare and to include the right of public assistance in the demands around the Poor People’s Campaign. So again, we see him moving and changing on these issues, as well.

Hagopian: Yeah. I kind of related. I got a question from a student about King’s views on democratic socialism.

Theoharis: I mean, one of the things that we see increasingly in King, which is there in the 1950s, one of the things I think about King as he’s talking about things like Northern liberalism and capitalism in the 1950s, and then he just gets more and more strident about them, in part because people aren’t listening. It’s not that King’s critique of capitalism all of a sudden happened in 1967, though he certainly talked more about that. He’s certainly calling out the structures of capitalism and the ways these intertwine. People in the chat were talking about his Riverside speech against the war in Vietnam in April of 1967. That is also right; there’s a profound critique of us capitalism in there, and he’s linking militarism, capitalism, and racism, and talking about the interconnections of them.

Hagopian: Absolutely. It’s an incredible legacy that he left there that certainly never makes the corporate textbook. There’s a question about wanting more resources to study to learn more about Martin Luther King.

Theoharis: To me, the first place to start is to get a book that’s a compilation of King’s speeches. I love A Testament of Hope, but there’s a lot. Start by buying some of King’s books. As you were pointing out Jesse with the “I Have a Dream” speech, I think this is true in a much broader way, that we tend to consume King in snippets. I think the first place to start is to really just sit in King’s words and to really grapple with the breadth of what he’s talking about. If you have not read King’s Where Do We Go From Here?, I mean, this is not the King we’re taught in school. He’s really criticizing that kind of, he has this word, that comfortable vanity of white people, decent white people who think they’re committed to change, but aren’t really committed to very much change. So, that’s where I would start.

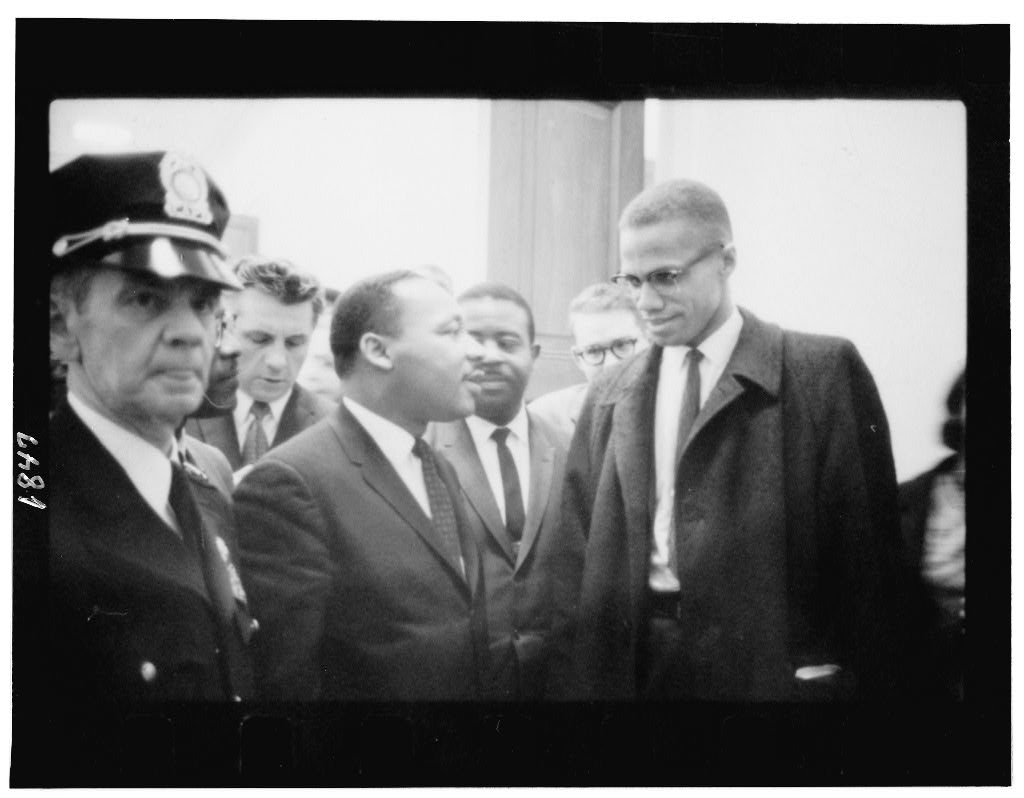

In many ways, you start to read him and then you see all these things that — whether it’s about the north, whether it’s about capitalism, whether it’s about militarism — all of these themes in there, that he’s just much fuller and richer. I see people talking about the relationship between King and Malcolm, and there’s this new book by Peniel Joseph that just came out around King and Malcolm and looking at their commonalities, The Sword and the Shield. Everyone should get that.

And again, if we’re going to talk about Coretta, she and Malcolm meet in January, about a month before he is assassinated. She’s very impressed by him and she’s devastated when he is assassinated, in part because she can see this as possibly happening to Martin, but also because of what she sees in him.

Hagopian: Yeah, absolutely. Two books that had a huge impact on my understanding of King and my political development have been Where Do We Go From Here?, which I think just lays out such a much deeper critique of America and the type of reshaping and massive amount of resources that we need, that it’s not just about bootstraps and having Black people take responsibility for themselves, which King gets painted as. But, when you look at his deep critique of America in that book and how we need to redistribute resources, especially for education, especially for teachers, that book is really vital. There’s a question in here about his relationship to Cesar Chavez. I don’t know if you can comment on that.

Theoharis: I don’t know enough to really comment on that. Sorry.

Hagopian: I want to do more research on that myself. A lot of people asked about Highlander.

Theoharis: There’s this funny moment. So, King doesn’t go to Highlander until 1957. They have this big 25th anniversary kind of celebration and that’s when King goes, and that’s when that photo is taken and is then plastered across the South calling King a communist and as attending a communist training school. One of the things that always makes me giggle is that at the Selma to Montgomery march at the end of the March, there are these huge billboards that the Klan puts up along the march with this picture. It’s King and Rosa Parks there at Highlander, and they’re calling it a communist training school. Rosa Parks, who always wanted to correct the record, said, “I was a student there, but he was not.” So, King does come to Highlander in 1957, but he’s not a regular at Highlander like some of the others, like Parks. Obviously, [there are] several clerks working there. Ella Baker’s there. Obviously, many of the SNCC leaders will come to Highlander. It’s not that he’s opposed to Highlander, because he comes to help celebrate in 1957, but Mrs. Parks would be like, “I studied there! He didn’t.” So that always cracks me up.

Hagopian: That’s incredible. Well, I have just one last question for you, to try to summarize the importance of Malcolm’s legacy. I think one of the things that you point out in your book, A More Beautiful and Terrible History, you argue that the hyper focus on individuals like King obscures how large the Black Freedom Struggle is and how long the fight has been going on. Can you talk more about what you meant by that?

Theoharis: One of the things about King, and King knows this, is that King goes to lots of places in the south and in the north and is hooking up with movements, in part to give more visibility or stature, but he’s hooking up with local organizers and movements all around the country, and this begins even when he gets his start in Montgomery. I think there’s this idea that Martin Luther King created the Montgomery Bus Boycott. That is sometimes communicated in textbooks, when the Montgomery Bus Boycott catapults to national attention. But, in fact, it is created, put in place, and pushed forward by a whole host of people that ultimately elevate King.

There are all of these activists on the ground that are laying the groundwork. There’s Jo Ann Robinson, from the Women’s Political Council; there’s people like E. D. Nixon; obviously Rosa Parks and Johnnie Carr; and then all of these women who are doing so much of the fundraising during the Montgomery Bus Boycott. So, at any moment we look at, there’s all these local activist people making this movement. Then, I think part of understanding what Dr. King is doing is also understanding that he is a little bit like, how would we say it, he’s hooking up with all these movements because he sees the importance of knitting together this struggle from Seattle to LA to Birmingham to New York to Pittsburgh to Jackson. And this is a huge burden. I mean, I think one of the things that we don’t think or grapple with enough is how hard, how depressed King was, how much of a toll this took on him. But, partly because he sees how he can help to illuminate what people are doing.

Hagopian: A burden, but also an incredible service he performed. So many people were engaged in struggles all around the country and he was able to help illuminate them and give them more credibility in some ways. So, thank you for sharing all those lessons with us. I think that people leaving today will have such a better understanding of not only King’s legacy but how to take stands on issues today, whether it’s around militarism and war, whether it’s around corporate greed and capitalism, interracial organizing, police brutality, health care, poverty. There are just so many issues that we covered today. I want to thank everybody for joining us today.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Key Resources

Here are some of the materials mentioned by the presenters and in the chat box.

|

|

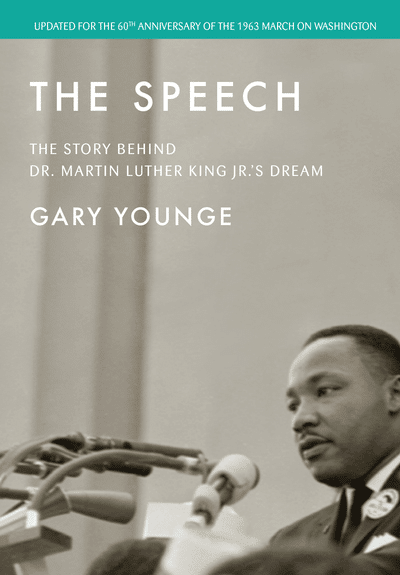

BooksA More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History by Jeanne Theoharis A popular historiography that critiques the traditional narrative and challenges educators to revamp curriculum to include a fuller, more critical history of the civil rights era. The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. by Peniel E. Joseph A biography of Malcolm and Martin and the movements they came to define. |

|

|

A Time to Break Silence: The Essential Works of Martin Luther King Jr., for Students by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. This collection can be used to introduce King, as Jeanne Theoharis suggested, in his own words. The Radical King by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Twenty-three selections that underscore King’s identification with the poor, his unapologetic opposition to the Vietnam War, and his crusade against global imperialism. Want to Start a Revolution: Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle edited by by Dayo Gore, Jeanne Theoharis, and Komozi Woodard The Chicago Freedom Movement: Martin Luther King Jr. and Civil Rights Activism in the North by Mary Lou Finley |

|

ArticlesDon’t Forget That Martin Luther King Jr. Was Once Denounced as an Extremist by Jeanne Theoharis What King Said About Northern Liberalism by Jeanne Theoharis ‘I Am Not a Symbol, I Am An Activist’: The Untold Story of Coretta Scott King by Jeanne Theoharis Why Coretta Scott King Fought for a Job Guarantee by David Stein Martin Luther King Jr. and Public Health by Ana V. Diez Roux |

|

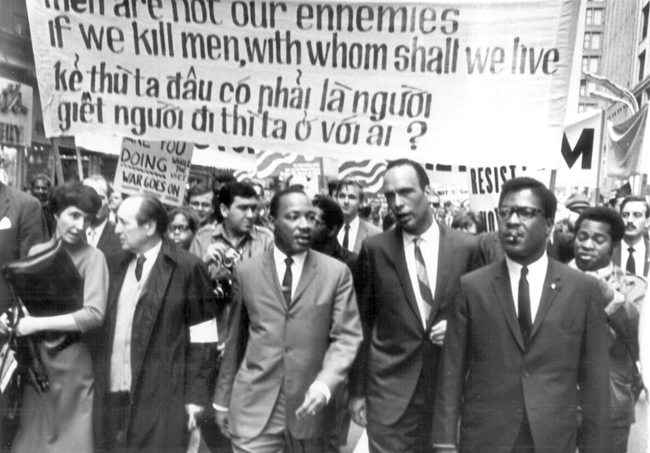

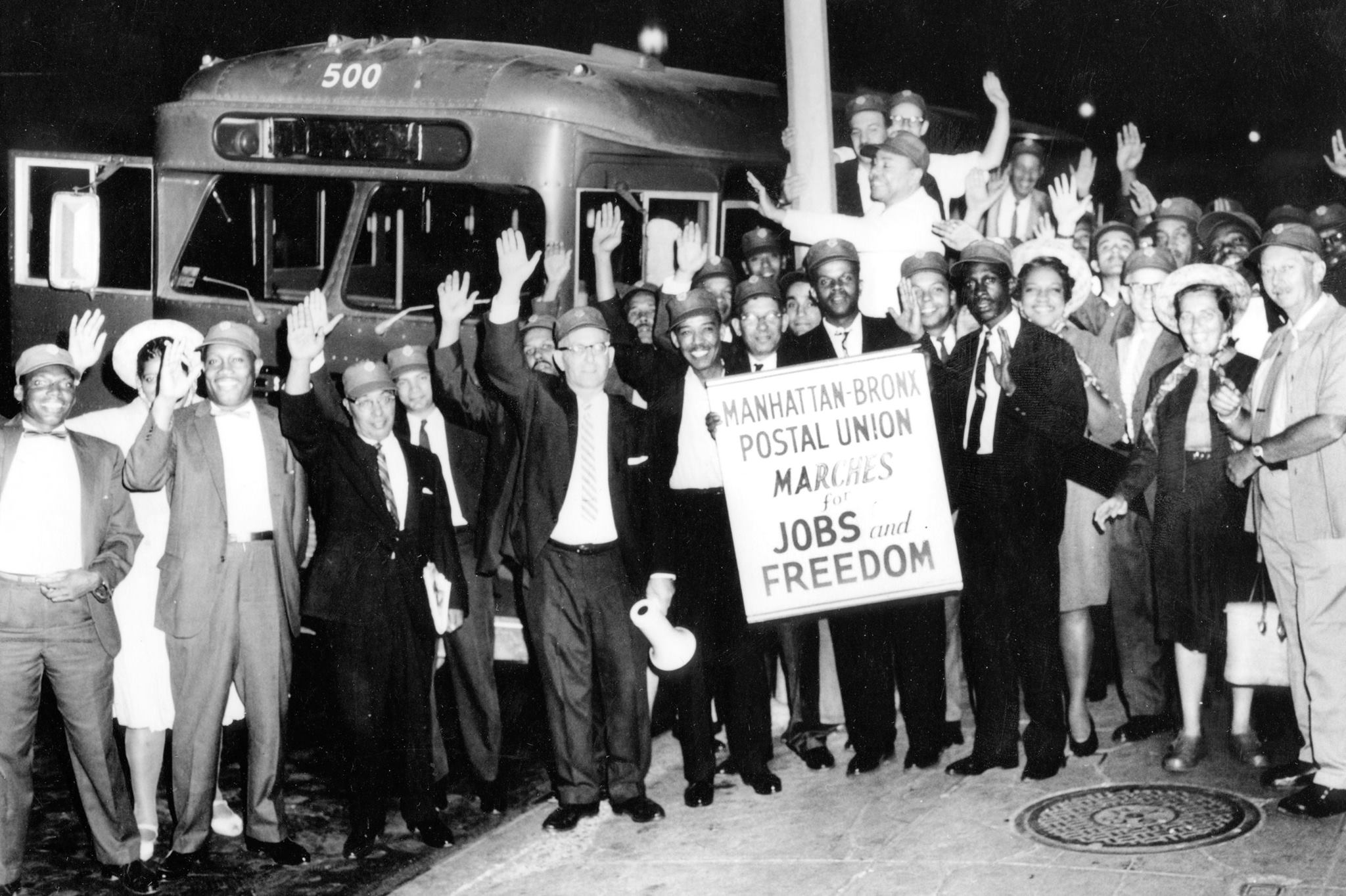

Photo by Jo Freeman. Photo by Jo Freeman. |

Lessons and Teaching IdeasA Revolution of Values by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Text of speech by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on the Vietnam War, followed by three teaching ideas. COINTELPRO: Teaching the FBI’s War on the Black Freedom Movement by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca. Through examining FBI documents, students learn the scope of the FBI’s COINTELPRO campaign to spy on, infiltrate, discredit, and disrupt all corners of the Black Freedom Movement. |

|

Find more lessons, books, films, and articles to teach outside the textbook about Dr. Martin Luther King and the Civil Rights Movement in Related Resources at the end of this page.

Participant Reflections

Here are some of the responses from participants in the session evaluation.

What was learned.

Analyzing the WHOLE speech from the March on Washington and talking about Coretta Scott King and other women’s organizing = way to increase student engagement with what has become a boring subject to them (the sanitized version of King).

I think learning more about the role of Coretta Scott in shaping King’s view is revolutionary to my understanding. I intend to focus more on the women in the movement and look into more primary source documents from the women leaders in the movement at the same time.

I didn’t realize that Dr. King was not liked during his time and that people are reacting the same way to BLM and Poor People’s campaign as they did to him during his time.

I learned about the intricacies of King’s work, especially in regards to his stance on northern racism, police brutality’s and the Poor People’s Campaign. I look forward to incorporating this into my new school’s curriculum!

I was able to get so many good book recommendations and speech references to look up. I can’t wait to use them to deepen my understanding. Everything I’m learning is helping me to resist the oversimplified and sanitized version of history that allows these injustices to be reborn and repurposed.

In the breakout room, I loved hearing from Rukaya — a high school student in Seattle — about why learning the radical version of Dr. King is so important to her. She described how it helped her realize that modeling her own life around leadership in the Civil Rights Movement didn’t have to be Malcolm X or Dr. King. Rukaya likes knowing about the complexity of Dr. King’s life and admires his firm stance on housing and economic justice. In my classroom, I want to help students meet people from history who guide their decision making. The radicalized Dr. King offers students more than a charismatic preacher; this Dr. King offers more wisdom and possibility for the choice points that will inevitably come up for students. This was a cool connection that I will certainly hold in my heart as I incorporate historical information about Dr. King to my curriculum. I also really appreciate the focus on systemic racism beyond the South. As a teacher in the Northeast, I hear the myth about Southern-only discrimination, and it was helpful to see how Dr. King was in Seattle, Los Angeles, and New York! More content to help un-do this troublesome idea.

The early life of Coretta Scott King and her influence in the anti-Vietnam War Movement. As a high school Social Studies teacher, I plan on using this information as a supplement to discuss US imperialism and militarism past and present with my seniors. This can take the form in both government and economics curriculums.

The most important thing I learned was a deeper insight on the trials of Dr. Martin Luther King before he was the King. I will use what I learned to educate my peers on the history that wasn’t taught.

The format.

I liked the combination of pre reading, lecture, and break out room.

These workshops are giving me life! As a teacher its great to meet with other likeminded educators

I loved the format, again. I liked the structure of master narratives/truths that Jeanne used as a way to understand more of the complexities/truth of the history. Breakout group was nice to be able to talk to people. Maybe a bit more time in the breakout groups to get a little deeper in our conversations.

It was awesome. I liked the expanded time in breakouts and 3 minute warning, I felt a beginning and closure to the conversation.

Loved the breakout groups and the designation of a facilitator. Thank you for calling out an equity norm before the breakout. Also, this was probably the only zoom I’ve been in where the chat was actually just as interesting as the speaker.

Was a great session. Good format. Nice to let everyone chime in and share a verbal goodbye in the end. Solidarity is great. Maybe we could end with a promise to concrete action….. Thanks and respect!!!

LOVE these sessions so much. As I wrote in the chat, they are a very, very silver lining of coronavirus.

ZEP note: Overall, about 85% of people said they like the breakout groups and many want to them to be longer. A few people commented that their breakout group did not work well — in most cases because it lacked a facilitator or some participants logged off.

Quotes by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Here are quotes by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., some of which were shared by Jeanne Theoharis during the session.

In Saturday Review in November 1965, three months after Watts uprising.

In my travels in the North, I have become increasingly disillusioned with the power structures there… [who] welcomed me to their cities and showered praise on the heroism of Southern Negroes. Yet when the issues were joined concerning local conditions, only the language was polite; the rejection was firm and unequivocal.

As the nation, Negro and white, trembled with outrage at police brutality in the South, police misconduct in the North was rationalized, tolerated, and usually denied.

Speaking to a multiracial audience at the Urban League anniversary in NYC in 1960.

. . . a pressing need for a liberalism in the North that is truly liberal, that firmly believes in integration in its own community as well as in the deep South . . . who not only rises up with righteous indignation when a Negro is lynched in Mississippi, but will be equally incensed when a Negro is denied the right to live in his neighborhood. . . or secure a top position in his business.

Refuses to condemn Brooklyn CORE’s planned stall-in around the World’s Fair in 1964.

I hear a lot of talk these days about our direct action talk alienating former friends. I would rather feel they are bringing to the surface latent prejudices that are already there. If our direct action programs alienate our friends . . . they never were really our friends.

Chicago

As long as the struggle was down in Alabama and Mississippi, they could look afar and think about it and say how terrible people are. When they discovered brotherhood had to be a reality in Chicago and that brotherhood extended to next door, then those latent hostilities came out.

On false narrative of crime in 1967.

When we ask Negroes to abide by the law, let us also demand that the white man abide by law in the ghettos. Day-in and day-out . . . he flagrantly violates building codes and regulations; his police make a mockery of law; and he violates laws on equal employment and education and the provisions for civic services.

More on ‘crime.’

The policymakers of the white society have caused the darkness; they create discrimination; they structured slums; and they perpetuate unemployment, ignorance and poverty. It is incontestable and deplorable that Negroes have committed crimes; but they are derivative crimes. They are born of the greater crimes of the white society. . . The slums are the handiwork of a vicious system of the white society.

In Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?

Negroes have proceeded from a premise that equality means what it says. . . But most whites in America, including many of goodwill, proceed from a premise that equality is a loose expression for improvement. White America is not even psychologically organized to close the gap — essentially, it seeks only to make it less painful and less obvious but in most respects retain it. Most of the abrasions between Negroes and white liberals arise from this fact.

Speakers

Jeanne Theoharis is a distinguished professor at Brooklyn College. She is the author or co-author of nine books and numerous articles on the Civil Rights and Black Power movements and the politics of race and education. Her books include the award-winning titles The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks and A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, and editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing.

More Sessions

Read about and register for more sessions.

Please make a donation so that we can continue to offer people’s history lessons, resources, workshops — and now online mini-classes — for free to K-12 teachers and students. We receive no corporate support and depend on individuals like you.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn