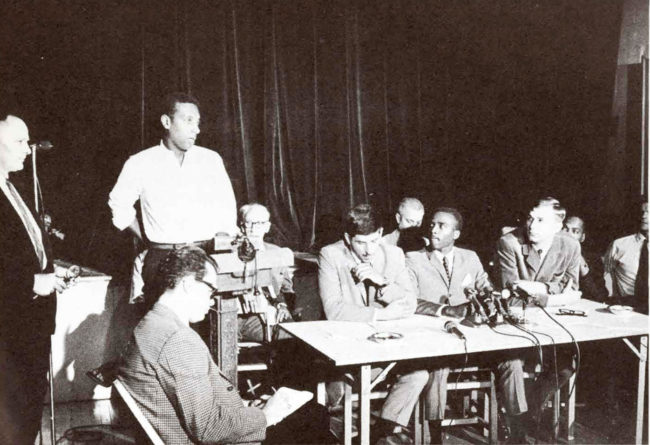

Dennis Mora, James Johnson, and David Samas at the June 30, 1966 press conference announcing their refusal to be sent to Vietnam. Source: Finer/Memorial University of Newfoundland

By Derek Seidman

On June 30, 1966, dozens of people assembled in the basement auditorium of the Community Church in mid-town Manhattan for a big announcement. Journalists and photographers were there, and so were key leaders of New York’s antiwar left, such as A. J. Muste and Dave Dellinger. Stokely Carmichael, the chairperson of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) who had recently begun to popularize the phrase “Black Power,” also showed up. All of them gathered to hear the words of three soldiers, Privates David Samas and Dennis Mora, and Private First Class James A. Johnson. The trio had been stationed at Fort Hood, Texas, and they had just been informed they were going to Vietnam. They were given a 30-day leave before they had to embark. The G.I.’s convened the press conference to perform a bold act: they intended to refuse their orders to go fight.

By June 1966, the U.S. had already been entangled in Vietnam for close to two decades, but its military aggression had taken a turn towards major escalation when President Lyndon Johnson began to send hundreds of thousands of ground troops beginning in 1965. This was accompanied by the onset of a three-year bombing campaign in the north. Antiwar protest grew almost right away, with two mass demonstrations in 1965. By mid-1966, it was clear to many that the war wasn’t going away, and antiwar organizers, mostly long-time pacifists, students, and old radicals, began to deepen their commitments and try to broaden their coalition to include new constituencies.

One of these constituencies was soldiers. Antiwar organizers in New York had consciously sought out refusers and veterans to speak at their events. The most famous antiwar veteran up to that point was probably Donald Duncan, who served as a Green Beret in Vietnam. But civilian organizers saw military personnel mostly as moral symbols whose presence in the movement could help disarm hawkish, pro-war opponents who red-baited protesters and criticized them as being against the troops. The notion that the antiwar movement might actually organize soldiers, or that they could help soldiers organize themselves, was yet a faint idea. It would take the actions of the troops themselves, of G.I.’s like Samas, Mora, and Johnson, to crack open the possibility for a G.I. movement.

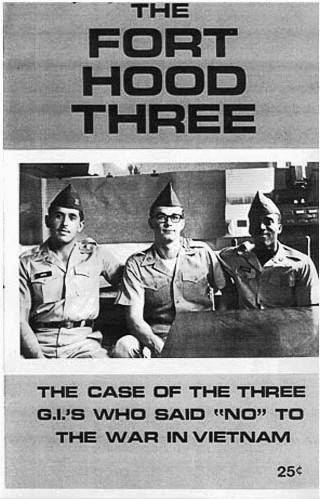

Read the Fort Hood Three’s statements and letters of support in this pamphlet (PDF).

The three G.I.’s had prepared a statement to read to the assembled crowd in the church auditorium. “We have decided to take a stand against this war, which we consider immoral, illegal, and unjust,” they declared. They planned to report to the Oakland Army Terminal, “but under no circumstances” would they embark for Vietnam, even if their refusal resulted in courts-martial. They spoke not only for themselves. “We have been in the army long enough to know that we are not the only G.I.’s who feel as we do. Large numbers of men in the service do not understand this war or are against it.” They explained how the soldiers around them became resigned to going to Vietnam. “No one wanted to go,” they said, “and more than that, there was no reason for anyone to go.”

They criticized U.S. support for the government and military of South Vietnam, and they questioned the entire purpose of the war itself. In the army, they said, “No one used the word ‘winning’ anymore because in Vietnam it has no meaning. Our officers just talk about five or ten more years of war with at least half-million of our boys thrown into the grinder.” The three young men agreed on one thing: “The war in Vietnam must be stopped.” The time for talk was over. They ended their statement: “We want no part of a war of extermination. We oppose the criminal waste of American lives and resources. We refuse to go to Vietnam!”

The three G.I.’s first met at Fort Gordon, Georgia, where they were stationed before they were reassigned to the 142nd Signal Battalion of the 2nd Armored Division at Fort Hood. They bonded over their shared critique of the war. They all had opposed the war before entering the army, but now, with shipment to Vietnam looming, the stakes were much higher.

All three came from working-class backgrounds, and they all had some college education. Mora was Puerto Rican, Samas was Lithuanian and Italian, and Johnson was African American. “We represent in our backgrounds a cross section of the Army and America,” they said. Mora was from Spanish Harlem and was a member of the Du Bois Club, a youth group connected to the Communist Party. He had participated in protests against U.S. foreign policy in Vietnam, Guatemala, and Puerto Rico. A classmate described him as “a socialist who’s interested in the Marxist way of thinking.” Mora’s links to the New York left proved helpful when the three troops decided to act on their consciences.

After being ordered to Vietnam, the soldiers decided together that they would refuse. During their leave they hashed out a strategy and reached out to a lawyer. With Mora’s connections to the antiwar left, they sought out civilian allies. They contacted leaders of the Du Bois Club and the Fifth Avenue Vietnam Peace Parade Committee. Antiwar leaders Dave Dellinger and Fred Halstead met with the G.I.’s, and together with famed pacifist A.J. Muste, they all agreed to use the Parade Committee, perhaps the most important antiwar coalition at the time, to mobilize support for the three. They also agreed to use their refusal as a call to organize more G.I.’s against the war.

June 30 press conference included members of the peace movement, the Civil Rights Movement, and soldiers. (L-R): Dave Dellinger, Stokely Carmichael, A.J. Muste, Dennis Mora, James Johnson, David Samas, Lincoln Lynch, and Staughton Lynd. Source: Finer/Memorial University of Newfoundland

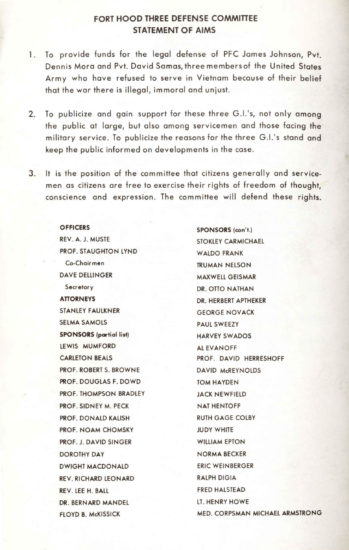

This was the beginning of a civilian-soldier alliance that would help sustain the wave of G.I. protest to come. The organizers in New York worked to mobilize broad, national support for the soldiers. They formed the Fort Hood Three Defense Committee and sent out fact sheets to their contacts across the nation. They lined up support for the G.I.’s on the west coast, and they reached out to luminaries like Carmichael.

All this represented an important turning point in the antiwar movement. Dellinger wrote that the peace movement had been “slow” in the past to “carry its message to the soldiers.” David Samas echoed this point. “It often seems that the peace groups are united against the soldier,” he wrote. “The G.I. should be reached somehow. He doesn’t want to fight. He has no reasons to risk his life. Yet he doesn’t realize that the peace movement is dedicated to his safety.” The three G.I.’s and their antiwar allies were heeding Samas’ words and showing the potential for a new path: soldiers and civilians, in alliance, working together to take the peace movement into the army’s ranks.

Click to read the Aims of the Fort Hood Three Defense Committee. Image: Finer/Memorial University of Newfoundland.

It was opposition to the war that drove the three soldiers to act, but their critique of racism and support for the Civil Rights Movement were also major motivations. They were some of the earliest antiwar protesters to really connect opposition to the war abroad to the fight for racial equality at home. “We know that Negroes and Puerto Ricans are being drafted and end up in the worst of the fighting all out of proportion to their numbers in the population,” they said at their press conference, “and we have firsthand knowledge that these are the ones who have been deprived of decent education and jobs at home.” In a speech he was scheduled to give, Johnson discussed the “direct relationship between the peace movement and the civil rights movement,” and he drew a connection between the Vietnamese and African-American struggles. “The South Vietnamese are fighting for representation, like we ourselves,” he wrote. “[T]he Negro in Vietnam is just helping to defeat what his Black brother is fighting for in the United States.”

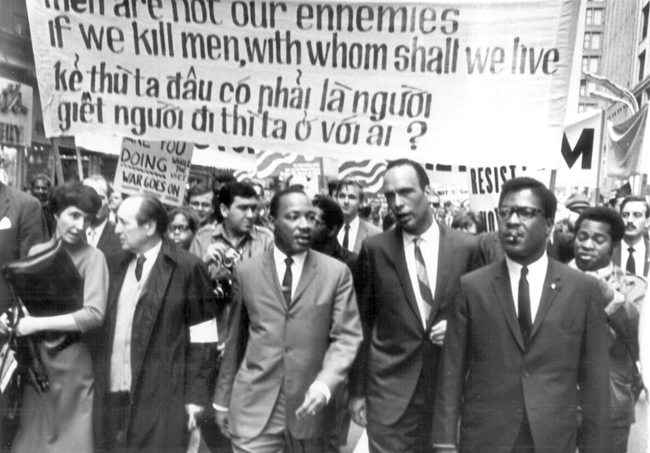

Johnson also highlighted the contradiction for Black soldiers who were asked to fight abroad while being denied equal rights at home. “When the Negro soldier returns, he still will not be able to ride in Mississippi or walk down a certain street in Alabama,” he wrote. “His children will still receive an inferior education and he will still live in a ghetto. Although he bears the brunt of the war he will receive no benefits.” Nor was it just these three G.I.’s who were connecting the dots between racism and the war. Their act of protest occurred within months of Muhammad Ali’s draft refusal and the rise of the Black Panthers, who connected colonialism abroad to racial oppression at home. Martin Luther King Jr. would soon speak out against the war. “We were taking the Black young men who had been crippled by our society,” King would later declare, “and sending them eight thousand miles away to guarantee liberties in Southeast Asia which they had not found in southwest Georgia and East Harlem.”

After that June 30th day when the G.I.’s publicly declared their refusal to go to Vietnam, they were transformed into a cause célèbre. But it wasn’t just sympathizers in the peace movement who were paying attention to them. The police went to Samas’ home and urged him to retract his statement, and they spoke to his parents to try to pressure him to back down on his refusal. Samas stood firm in his decision. “They have attempted to intimidate the three of us in one way or another,” wrote Samas. “But we have not been in the least shaken from our paths.”

On July 7, 1966, the three G.I.’s were once again scheduled to speak to supporters at the Community Church. Nearly 800 people turned out to the event. On their way there, however, Samas, Mora, and Johnson were stopped by the police and swooped away to Fort Dix, New Jersey. Unable to give their speeches, members of their families stepped in. James Johnson’s brother read his talk, and Dennis Mora’s young wife read her husband’s statement. Meanwhile, the army fretted over how to handle the detained G.I.’s. Fort Dix Commanding General J.M. Hightower told the army’s chief of staff that he had “sufficient evidence” to charge the three with “uttering disloyal statements with intent to cause disaffection and disloyalty among the civilian population and members of the military forces.” He decided, however, to issue movement orders to the soldiers to leave for Saigon on July 13. This would be their last chance at avoiding punishment. “Should orders be disobeyed,” Hightower wrote, “appropriate action will be taken.”

|

|

| LEFT: Family members of the Fort Hood Three demonstrate at Fort Dix on July 9. RIGHT: A. J. Muste confronts Fort Dix authorities at demonstration. | |

The orders to ship out actually came down on July 14, 1966. The young men were told they must go to Vietnam. They refused. In doing so, they became one of the very first examples of active-duty G.I. refusal during the Vietnam War, and certainly the most visible to date. They also became something more than just three soldiers. To the antiwar movement, they were now the “Fort Hood Three.”

The Fort Hood Three were court-martialed in September of 1966. In defense of their refusal, the soldiers argued that the war in Vietnam was illegal. The military refused this argument, and all three were convicted for insubordination. Samas and Johnson each received five years in prison at Fort Leavenworth. Mora received three years. All appeals would fail, including one to the Supreme Court, though the army would later reduce Samas’ and Johnson’s sentence to three years.

The Fort Hood Three Defense Committee continued to mobilize support for the G.I.’s after their conviction. They raised funds, spread awareness of the case, paid for newspaper ads, and circulated petitions. Sponsors of the defense committee included Tom Hayden, Stokely Carmichael, Harvey Swados, Noam Chomsky, Floyd McKissick, and others.

Some in the labor movement also rallied behind the soldiers. James Johnson’s father was a steward with the Retail, Wholesale, and Department Store Workers Unions (RWDSU). District 65 of the AFL-CIO had a Peace Action Committee that mailed a leaflet to members with the headline: “Jimmy’s Son Needs Your Help.” The flyer explained that “Jimmy Johnson is a 65er” who “takes his job and his union seriously,” and asked for readers to contribute to the G.I.’s defense fund and write to them with letters of support. Al Evanhoff, Assistant Vice President of District 65 of the RWDSU, put out a supportive statement. “As a trade unionist,” he wrote, “long ago I learned the fact that an injury to one is an injury to all.” Evanhoff criticized the war and pledged to form a defense committee for the Fort Hood Three.

This support from sections of the labor movement is worth noting, because it flies in the face of the conventional narrative that pits workers against the antiwar movement. While some union leaders and members were certainly pro-war, others opposed it. Major unions like the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), and powerful labor leaders like Walter Reuther criticized the war. Many locals and rank-and-file members were antiwar, and working-class people overall were more likely than the college-educated affluent to be against it. G.I. and veteran dissent would soon become one example of working-class antiwar protest to make a mark on history.

The support for the soldiers was translated into song by Pete Seeger, the famous Old Left troubadour. In his lyrics, Seeger paraphrased David Samas:

We’ve been told in training that in Vietnam we must fight;

And we may have to kill women and children, and that is quite all right;

We say this war’s illegal, immoral, and unjust;

We’re taking legal action, just the three of us.

We’ll report for duty but we won’t go overseas.

We’re prepared to face court martial, but we won’t fight for Ky.

We three have talked it over, our decision now is clear,

We will not go to Vietnam, we’ll fight for freedom here.

When the three soldiers were finally released after serving their time, the Hunter College Du Bois Club hosted a celebratory homecoming for them. It was called “Salute the Ft. Hood Three,” and Pete Seeger, Ossie Davis, Dave Dellinger, and others attended. The G.I.’s came out of prison, still, as supporters of the antiwar movement.

They also came out of prison to see a rising G.I. movement flourishing all around them. Hundreds of active-duty service members had joined the antiwar movement by the late 1960s. Some, like the Fort Hood Three, refused to go to Vietnam. Underground G.I. newspapers circulated throughout the military, and off-base coffeehouses were springing up around the nation. Antiwar soldiers marched, protested, petitioned, and formed their own groups to try to organize their fellow troops. Civilian support networks and legal defense organizations were aiding this rising tide of soldier dissent. And the G.I. movement had not yet reached its peak.

Little of this was true when David Samas, Dennis Mora, and James Johnson refused to ship to Vietnam on June 30, 1966. But a few years later, it was a reality. The Fort Hood Three set an example that others followed, and David Samas, Dennis Mora, and James Johnson emerged from their time in prison to see firsthand the G.I. movement that they helped to create.

Derek Seidman is an assistant professor of history at D’Youville College in Buffalo, New York. He is currently writing a book on the history of soldier protest during the Vietnam War. To reach him, or to see a version of this article with citations, contact him at seidmand@dyc.edu.

© 2016 The Zinn Education Project. Posted on: Huffington Post

I love what you guys are usually up too. Such

clever work and exposure! Keep up the awesome works guys I’ve added

you guys to our blogroll. http://www.yahoo.net