The Howard Zinn Centennial week of activities launched with a teacher workshop on the Red Scare. Why? Because the same tactics are being used today to try to thwart the teaching of people’s history.

More than sixty teachers from around the country signed on for the interactive introduction to the Zinn Education Project mixer lesson about the Red Scare.

Here are highlights from the session, facilitated by Zinn Education Project team members Cierra Kaler-Jones and Ursula Wolfe-Rocca. Michael Koncewicz of the Tamiment Library (NYU) shared primary documents.

Introduction

The workshop opened with a with a quote from Howard Zinn,

These words take on new resonance at a time when state legislatures and school boards across the country are enacting policies to curtail what educators in public schools and universities can say and teach about reality and history. There have already been some high profile cases of teachers being fired as a consequence of the gag rules. But even more terrifying than those relatively rare cases is the chilling effect of these laws. Afraid for their livelihoods, we know that more teachers will feel safer if they stick to the textbook, the standard narrative and curriculum.

So what do they get if they stick to the textbook?

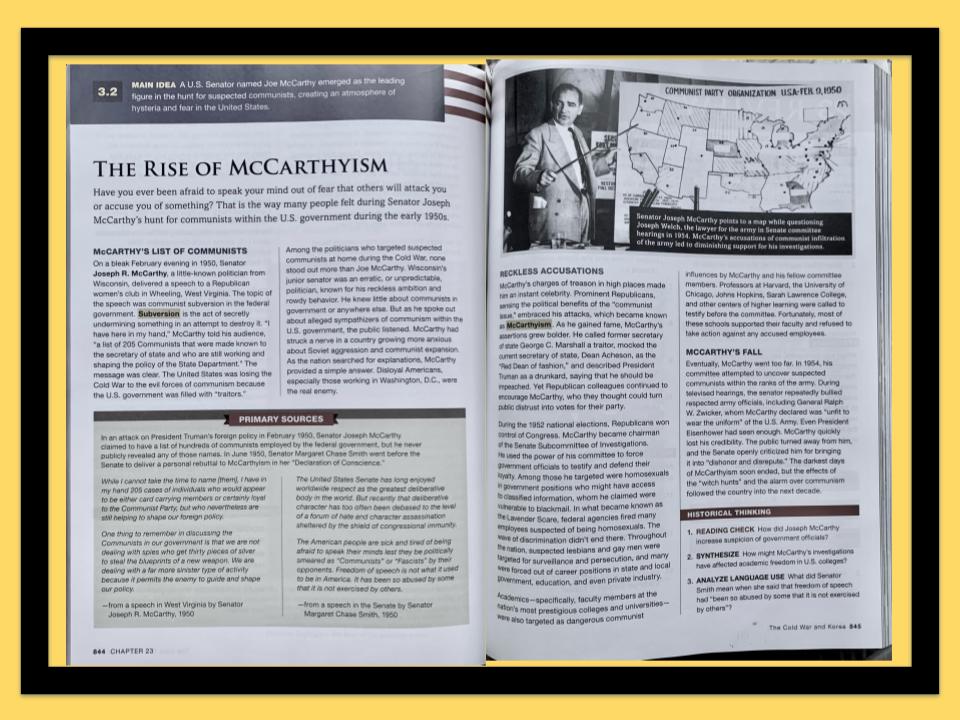

The answer can be found on these pages on McCarthyism from the 2019 National Geographic U.S. history textbook (America Through the Lens).

In the textbook:

-

- The Red Scare is reduced to the buffoon-like character of McCarthy, as if he were an anomaly, and as if there was not a larger, more pervasive political infrastructure of suppression.

- The words “African American” or “Black” do not appear anywhere. The words “labor,” “activist,” or “organizer” do not appear. We learn almost nothing about the people who were targeted.

- “The darkest days of McCarthyism soon ended.” This typical textbook treats the Red Scare as a discrete event or era rather than an ongoing politics that has been mobilized throughout U.S. history to neutralize progressive challenges to the status quo.

So that is the history we get if Republican policymakers get their way. What are the costs of this distorted and incomplete view of the past? James Baldwin offers an insight,

The facilitators noted,

So we are here today to learn history we can use.

And we invite you to hold that in your consciousness as you move through today’s activity: How is this history useful? How does it clarify and illuminate our current moment?

Mixer Lesson

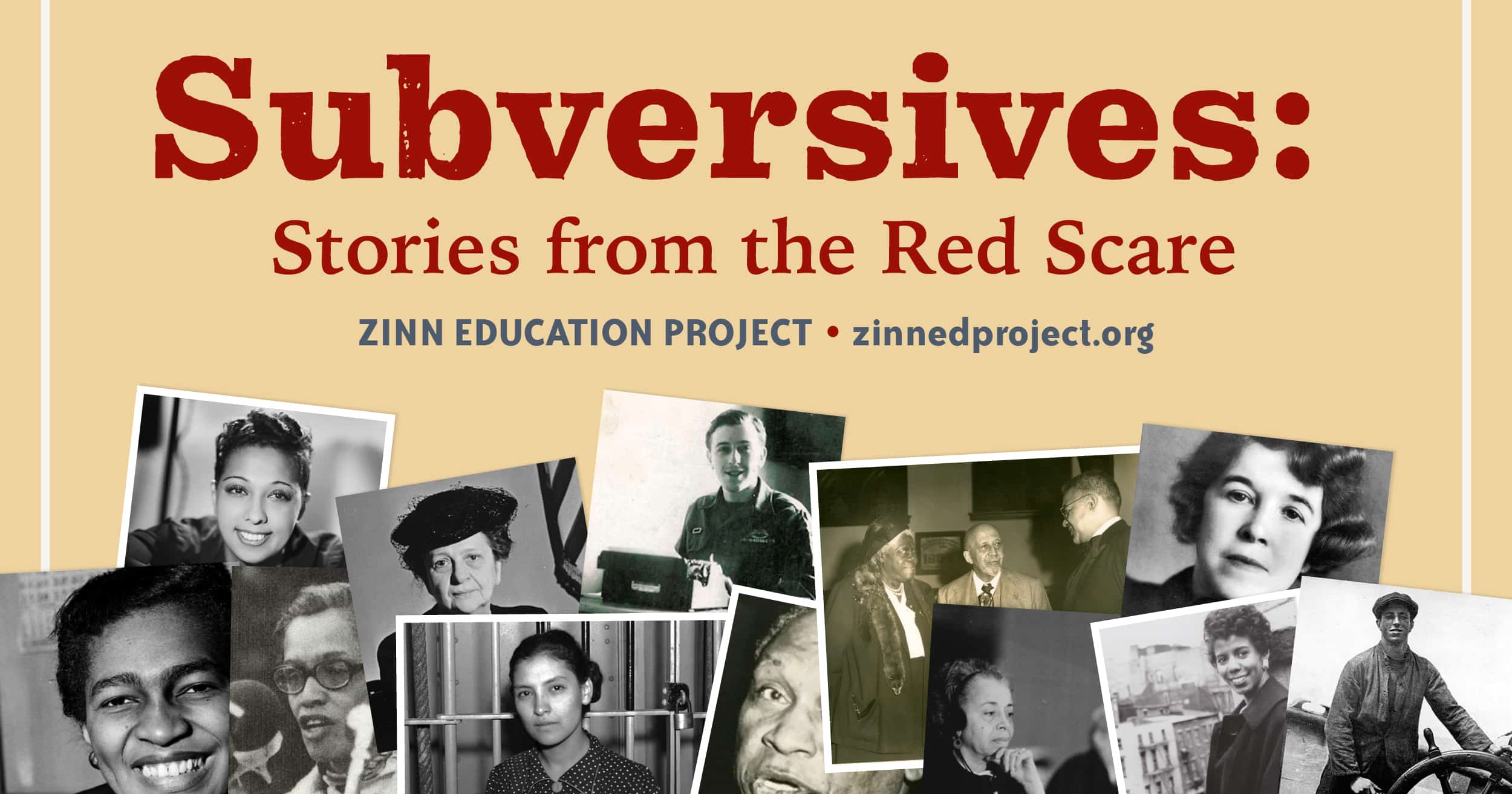

To engage the participants in the lesson, everyone was assigned a bio of one of 27 roles in the lesson, each one a target of government harassment and repression during the Red Scare. The names include:

-

- Esther Cooper Jackson, Southern Negro Youth Congress

- Frank Kameny, Mattachine Society of Washington

- Harry Bridges, International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU)

- Louis Jaffe, New York City Teachers Union

- Emma Tenayuca, Workers Alliance of America

- Claudia Jones, Communist Party

- Lorraine Hansberry, Inter-American Peace Conference

- W. E. B. Du Bois, World Peace Council

- Frances Perkins, Department of Labor

- Elizabeth Catlett, Taller de Gráfica Popular

- Charlotta Bass, Sojourners for Truth and Justice

- and more.

The instructions were to read their role and prepare to have conversations with fellow participants who learned about someone else. Then they were sent to breakout rooms in groups of three with the assignment to look for patterns and to gather information and insights. After three rounds of breakout rooms, they returned to the full group bubbling over with stories about the people they’d “met” and comments about how they wish they’d learned this before.

Primary Documents

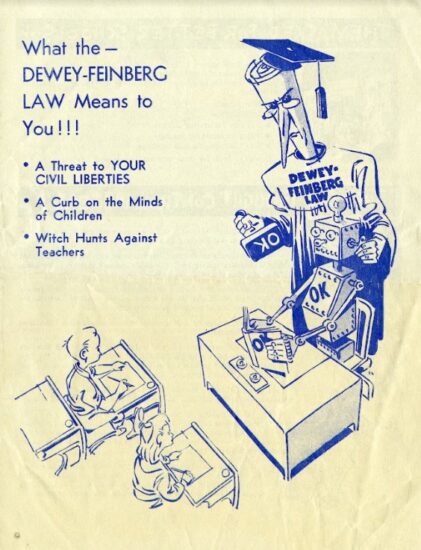

Michael Koncewicz, the Michael Nash Research Scholar at the Tamiment Library, shared a collection of documents from a 1940s investigation of “subversive activities” in New York City education.

Michael Koncewicz, the Michael Nash Research Scholar at the Tamiment Library, shared a collection of documents from a 1940s investigation of “subversive activities” in New York City education.

Participants were assigned different documents and then met in small to compare notes on what they learned and the relevance of the documents today.

Insights and Action

To process all they had learned, participants met in small group to discuss:

-

- Who was targeted during the Red Scare? What did they have in common?

- What were the consequences of the Red Scare for those who were targeted?

- Why is this history relevant to our moment? How can we “use” it?

Reflections

In a closing evaluation, participants responded to questions about what they learned and how they might use it. Here are some of their reflections,

The connections between the Red Scare and today are very real and very pressing for my students. I teach in Indiana, where trans girls are barred from participating in school sports and anti-CRT legislation is an ever-present threat. Some of my students feel as if the world is suddenly turning upside down and these documents and articles can really work to show them that people who think and love and believe in ways that challenge power have long been targeted, long been struggling, and long survived. Today was most valuable in providing a wealth of resource to dig into with students and really opening my eyes to how much is out there and accessible. — teacher, Indianapolis, Indiana

Reading statements from the students and colleagues of the Foner family was really moving and reminded me of why we teach and advocate for our students and critical thinking. — teacher, Arcata, California

I like the personalizing of the experience of this time period through learning about specific individuals that were targeted/labeled as “subversives.” Students can really connect with individuals and help grasp the larger concept/history and possibly see the links to their present. — teacher, White Plains, New York

There is so much to unpack with this lesson. The mixer has such great voices from the past. I feel the students will be able to really understand the Red Scare and how people pushed back from it. The resistance is important to teach our students. So many times they think people just gave in and allowed things to happen. I appreciate that this lesson shows everyday people working for change. — teacher, Houston, Texas

Although I knew about the McCarthy era, I never heard personal stories and got to hear about how harrowing and distressful the accusation of being a communist was and the brutal consequences it had for so many innocent people. I also learned some good techniques for using this material. — teacher, Albany, California

I will use this material to enrich my unit on Lorraine Hansberry and the other writers prosecuted in the Red Scare. I loved the content and meeting the different people in the breakout rooms. Much better than just reading it or watching a video. Thanks so much for this. It is tough in Oklahoma now. — teacher, Norman, Oklahoma

EXTREMELY well done, in both content and format conception!! Really appreciated the opportunity to connect directly with fellow participants! — teacher, Portsmouth, New Hampshire

I liked the short assignments we shared out in the breakouts and the tip about writing a moment before joining discussion — good teacher move. — teacher, Baltimore, Maryland

I am a teacher and plan on trying this strategy in my class. I like the idea of having students read about historical figures and then share what they read. This is more effective than having me lecture about these figures, leaving students nothing to talk about. The facilitators were well-prepared and used technological tools effectively. — teacher, Las Cruces, New Mexico

A life-changing session for me, and I bet for many other first-generation immigrants like me. — teacher, Silver Spring, Maryland

The lesson is available at the Zinn Education Project website for teachers to download and use in their classrooms. Let us know if you use the lesson.

In Memoriam

One of the people in the lesson, Esther Cooper Jackson, died on the day of the workshop at the age of 105. She was one of the founding editors of the magazine Freedomways and active in SNYC. Her papers are housed at the Tamiment Library.

Below is her role from the lesson.

Esther Cooper Jackson

Southern Negro Youth Congress

I was born in Virginia in 1917 to two parents who taught me to hate injustice. From my mother, I got an interest in doing something about the Jim Crow situation in which we lived. From my father, a decorated World War I vet, I learned to hate war — he came home a pacifist and turned me into one too. But it was at Fisk University in Nashville where I studied sociology and became even more committed to changing society. As part of my work, I interviewed Black women who worked as domestics in white homes during the Great Depression, and it was from them that I learned about what it meant to be triply oppressed — as poor people, Black people, and women. I was also part of a faculty study group, made up of both white and Black professors, who came together to read, discuss, and organize for a better world.

That’s how I was introduced to and joined the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA). No other political organization at the time combined the things I was most concerned about — economic and racial justice, anti-fascism, women’s rights. I met my husband, James, through that circle of friends and colleagues. He was in the CPUSA too, and he had founded the Southern Negro Youth Congress (SNYC) in 1937. I became its secretary not long after. SNYC organized a unionization campaign for Black tobacco workers in Virginia, anti-lynching campaigns across the South, and sponsored all sorts of political education. One of my favorite projects was the Caravan Puppeteers, a political puppet show put on by SNYC members to alert rural Black people about their right to vote. But by the late ’40s we were being attacked on all fronts.

In Alabama, where SNYC was headquartered, we couldn’t find places to meet safely. Some churches and meeting halls were willing to let us use their space, but pretty soon the police would show up and arrest us for breaking state segregation laws (since SNYC was always an interracial group). The government also harassed us for harboring “communists” in our organization. In 1951, my husband was indicted under the Smith Act, accused with dozens of other CPUSA members of “advocating the overthrow of the U.S. government.”

He went into hiding rather than give himself over to the U.S. courts. SNYC was harassed out of existence. My family was torn apart. And for what? For organizing the lowest paid workers in the country for better wages? For teaching Black Southerners about their right to vote?

We hope this brief bio encourages you to read more about Cooper Jackson’s extraordinary life and the other people featured in the lesson.

It is important to note that there are countless more stories. Students can research and write more roles as a follow-up activity. Let us know if they do.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn