On October 7, 2024, educator Brian Jones spoke with Jesse Hagopian about the history of the Civil Rights Movement in the North and ways that those stories can be included in the curriculum. This Teach the Black Freedom Struggle class was hosted in collaboration with the New York City Civil Rights History Project.

In the excerpt below, Jones describes the formation of an early Black Panther Party in Harlem to demand better schools.

The importance of making sure we understand that segregation and racism are foundational, which means it happens everywhere in the United States.

The reminder that our classrooms and schools are sites of resistance.

Tonight’s event will inform the work I am doing with the social studies department in my school to link present day civic engagement with the freedom struggles of the past. The primary source documents are particularly helpful, and those documents also point toward the opportunities for local research here as well.

Thinking that the North was simply de facto segregation absolves the North of any wrongdoing and invalidates a lot of our nation’s history while also turning a blind eye to injustices in the North.

The primary sources are really eye-opening. I am struck by the many faces of Jim Crow and the “small print” that allows injustice to continue. The idea of framing civil rights studies through examination of schooling makes sense for so many reasons.

Living in Cheyenne, Wyoming, I needed this connection with others who are trying to empower our students.

Event Recording

Recording of the full session, except for the breakout rooms.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): This session is in collaboration with the New York City Civil Rights History Project. We will share links relevant to documents at that site during the session, and we encourage everyone to go to this website and explore its resources more fully to think about how you might use this in your classroom or with your kids. Well, now I am so happy to welcome Brian Jones, who was an elementary school teacher for nine years in Harlem, director of the Center for Educators and Schools at the New York Public Library, author of The Tuskegee Student Uprising: A History, and the co-director of New York City Civil Rights History Project. Even more importantly for me Brian is an incredible mentor to me and friend who has been one of the most important people to me for learning about the Black Freedom Struggle. So, I’m really happy to be able to welcome you to this forum, Brian. It’s great to be with you again.

Brian Jones: Wow! Thank you for that generous introduction. I can say the same thing about you. This is really amazing to be here. Congrats to you and everybody here at the Zinn Ed Project and to the interpreters. I just think this is an amazing forum and an amazing resource, and I’m honored to be here.

Hagopian: Awesome. I’m so glad we worked this out. I’ve learned an incredible amount from you about the Black Freedom Struggle north and south, and it’s really great to expand people’s understanding about what the Civil Rights Movement is. So, I wanted to start by asking you when people think about the Civil Rights Movement, they usually think about the movement in the Southern states against formal Jim Crow. And this powerful movement is certainly important to teach about. It often doesn’t get taught about very much at all, even the Southern version. But, I think it’s also vital to teach about the movement against segregation and systemic racism in the North. So I was hoping we could start with you giving us a framework for how to understand the Civil Rights Movement of the North and what was its relationship to the Civil Rights Movement in the South?

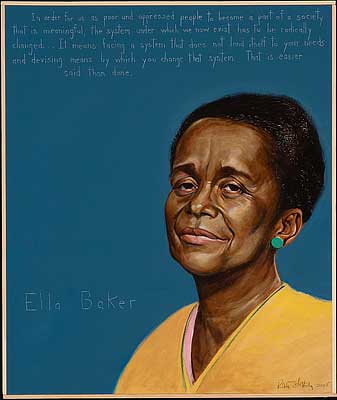

Jones: Well, this is from somebody who wrote a book about the movement in Tuskegee, Alabama. I think the first thing — and I know there are some movement veterans on the Zoom here whom I’m sure will agree — is that there are people whose stories of struggle and organizing are not just Southern stories, but their stories of organizing are North, South, and in some cases, East and West. You can’t contain somebody like Ella Baker and explain her trajectory as an activist if you’re only going to look south of the Mason Dixon line. Long before she’s organizing NAACP chapters in the South and doing all of the things that we know her for — helping to found SNCC and all of the incredible contributions she made to the Southern Civil Rights Movement — but long before she was doing that she was trying to organize parents in Harlem to organize against what they saw as segregated and unequal schooling.

A lot of what I want to talk about today narrows down to schools as a site of struggle. Actually, I think there’s a lot that we can do just thinking about school. School runs like a red thread through the Black Freedom Struggle. Whether the movement begins in a school or arrives at a school, or is in fighting over the school or access to school, or trying to make a school, schooling, learning, liberation is always not too far away from the story in the Black Freedom Struggle. The other great thing about focusing on school as a teacher, that’s an institution your kids know. They know about school, so it’s a way in for those of you who want to teach.

One other thing to say, and Jeanne Theoharis — who, I think, is here with us — says this better than anybody, so let me try to poorly imitate her way of putting it. You asked about the importance of being aware of and teaching the Northern struggle, and I think, as Jeanne would probably say — and maybe help me say it better if she is able to jump on the call here — is that when we teach this as something walled off in the South, as a movement fighting to end segregation and racism down there in a bad place where people are doing bad things, then it is a way of trying to redeem the nation or bring us back to a narrative that’s about national greatness. See, even this sinful thing that we engaged in, we beat it, we marshaled our resources and we ended it. But if you take a different view, that segregation actually starts in the North, that actually it’s pervasive in the North, that the struggle is national and not just Southern, and on different terrains and different terms, certainly in many ways. But if you take the view that it’s a national problem then you don’t get out of it, you’re not letting them off the hook in the same way in terms of thinking about the country as a whole and what its responsibilities are to people living within its borders.

Hagopian: I love that, and I’m about to quote from Jeanne’s book, but, Jeanne, do you want to add anything briefly to what Brian said?

Jones: This is like Phone a Friend!

Jeanne Theoharis: I think, Brian, what you’re getting at, and I think, Jesse, what you’re about to get at, is this idea that we in the United States shine a light on injustice. There might be struggle, because that’s what’s so moving about the Civil Rights Movement narrative that is in our textbooks. But then injustice is beaten, and I think when you move to the North, when you move to the New York story we’re going to talk about today, on the one hand, the biggest civil rights demonstration in the history of the Civil Rights Movement they don’t win.

Jones: Yeah, before we get there, they just put in the chat the Black Panther letter about Operation Shut Down. Let’s bring up that slide for a minute. So, when I started at the New York Public Library, I actually started at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. I was there finishing my research about Tuskegee and then I got hired as associate director of Education and I was just a kid in a candy store. I basically couldn’t believe that I could just go into the archives and look at things, and that it was part of my job. It was amazing, and I looked with the eyes of a teacher because I thought, “Well, if I’m here, I’ll help teachers use these collections.” And basically this is still what I’m trying to do, but from a different office. One of the very first things I laid my hands on was this letter which astounded me. This is a letter to the Harlem community. One of the most astounding things about it is the date, August 20, 1966. It’s advertising that we’re going to launch a Black Panther Party in Harlem.

Now, when we read this closely — and this gets to what you’re asking about North and South — first of all, the letter explains a genealogy of the Black Panther idea. The Black Panther Party idea starts in the South in Lowndes County, Alabama, and it comes out of SNCC’s attempt to build a movement for democracy in the Black Belt. We know it’s going to go to Oakland and blow up. We know it’s going to go to the Bay Area. But in this letter it’s also coming to New York. And the thing about the date: the date is before Oakland. That’s August. Oakland blows up in October. So here, notice, they’re not focused on what the Oakland party was focused on, which is, rightly so, police brutality. It’s a Black Panther Party for Self Defense. This Harlem party that they’re trying to launch is focused on school, it’s focused on trying to transform schooling in Harlem.

By the way, notice that this is a typewritten letter. I got to interview somebody who was in the room. There’s a bunch of mostly teenagers typing out this letter in 1966. I asked some of the details. One of the things he shared was that this letter was typed at Yuri Kochiyama’s apartment. I said, “Why were you at Yuri Kochiyama’s apartment?” [He said] “Because she had a typewriter, that’s why.” I said, “Well, why focus on school? Why that focus?” And he said, “Because there was already so much activism about schooling. That was the hot issue that everybody was talking about. So if you want to get something started in Harlem in 1966, you hook into what people are already active around, and that was trying to change their opportunities in school.” I think that speaks volumes to what we’re talking about here, about a movement that’s linked to the Southern movement, that’s not just walled off North or South. It’s connected across regions and that is in many ways fighting for the same kind of democratic demands.

Hagopian: Yes, I love that. I love the way you connect those two movements and the research that you uncovered about this other Black Panther Party that was forming independently of the Oakland party and fighting around schools is incredibly valuable. Thank you for that research and breaking all that down for us. I wanted to just get a little bit more into this question of segregation, because segregation in the North has historically extended beyond schooling to include housing, employment, and so much more. I wanted to quote from Jeanne Theoharis’s book, A More Beautiful and Terrible History, where she writes, quote, “many scholars and journalists, since the 1960s, have clung to this false distinction between a Southern du jour segregation and a Northern de facto segregation, making Northern segregation more innocent and missing the various ways such segregation was supported and maintained through the law and political progress.” So, I was hoping you could help us understand how we should think about the relationship between Jim Crow segregation in the South and the segregation of systemic racism in the North — what are the similarities and differences, and how do we make sense of that?

Jones: Yeah, it’s so, so important. I have to admit I was so resistant to Jeanne’s thesis for so long, really. Finally, the more you learn about anything, the more you’re like, “Wow, okay, there’s another example. Wow, okay, there’s another example.” Even knowing that there were Northern struggles, etc. But, Jeanne and others have really done an amazing job of documenting the ways in which differently framed, different mechanisms, but sometimes enshrined very much in law, sometimes written down in law in various ways to enforce segregation in the North. New York, again, is actually a really good example. New York officially bars segregation in schooling in 1883. Yet it’s 2024, and we still have it, and they have figured out ways over the years, other mechanisms to enshrine it.

One thing that I just want to point out is that I first learned about this from Matthew Delmont’s book, his terrific book, challenging the premise that the real issue is busing and the push back against desegregation. What he observes and highlights, and I think we have a slide for this, is what got smuggled into the 1964 Civil Rights Act, that talk about people writing it down. In the context of the federal government prohibiting Jim Crow segregation, they actually wrote down a way that they were going to allow segregation in the North. And it was a Southern senator on the floor of Congress who called them out and said, “Oh, so I see what you’re doing. What you’re saying is that when I do it it’s now going to be illegal. But when you do it in New York City, in Chicago, in Philadelphia, it’s legal.” So, you see, this desegregation of public education and the definitions . . . I’m going to just read it real quick.

Desegregation means the assignment of students to public schools and within such schools, without regard to their race, color, religion, or national origin. But desegregation shall not mean the assignment of students to public schools in order to overcome racial imbalance.

They effectively say you can’t, and then in all the op-eds in the New York Times, everybody then officially denies what is going on in places like New York City. You could even call it Jim Crow. The activists and the Black families call it Jim Crow. They say, “No, we’re going to try to. We’re going to challenge this.” And they use those labels to attack it. This history has important overlap with the struggles for many elements of what you’re describing. What are civil rights about? We think of struggle for racial justice, the Black Freedom Struggle. There’s other important dimensions of the civil rights struggles, especially in schooling, that have important overlaps and ways in which they’re entwined, like the struggle for disability justice.

I’m sure you well know — I’ve heard you talk about this many times, Jesse — about the way that intelligence testing becomes one of these mechanisms to segregate schooling, sometimes creating different programs within an officially desegregated school. But then you use intelligence testing to resegregate the same school, so there’s a way in which ableism and racism work together to create and recreate segregation.

Here’s another resource. It’s a Black newspaper, which is pretty much always a good teaching tool, to just take some date and some topics and compare it to the New York Times. The Black owned and controlled New York Amsterdam News is really telling it like it is, and they are not caught up in the rationalizations that the New York Times is caught up in. They’re saying here, for example, in this article reporting on what’s happening in the so-called 600 schools where Black kids are getting tested — way disproportionate to their numbers — into special education, and really shunted off into even worse facilities and schools with even worse resources.

Hagopian: And what year was that article from.

Jones: It’s 1946.

Hagopian: Wow! And we’re still . . .

Jones: I mean, I bet every educator on this call sees their school in that article and in the words that you just used to describe it. The way that AP classes are predominantly white, and the General Ed classes are Black, and the way that we’ve used standardized testing to track and rank and sort children ever since the days of eugenicists who first designed these tests. There’s just so many ways that they continue to segregate. They have so many strategies, don’t they?

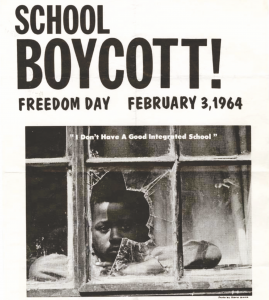

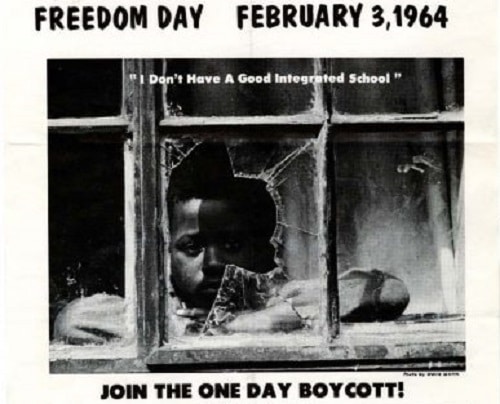

Hagopian: Incredible. I just wanted to stop and say that people should — I quoted from Jeanne’s book, A More Beautiful and Terrible History — people should check that out. And The Strange Careers of Jim Crow North. I highly recommend both these as sources for your classroom, and for a better understanding of what we’re talking about here. But, following from the last question, Brian, let’s talk about this huge moment that Jeanne alluded to earlier, the largest civil rights protest of the 1960s. Very few people would guess that it happened in the North. But, in fact, on February 3, 1964, nearly half a million students and teachers stayed out of school to protest the New York City Board of Education’s refusal to make a plan for comprehensive desegregation. So tell us, how did this happen? What’s going on with this fight?

Jones: Just the way you framed it, the largest protest in what we think of as the traditional civil rights timeline takes place in the North in New York City and takes place over schooling. Again, this is just an incredible moment. But New York is not alone; there are other cities that have similar protests in similar times. So it’s not an isolated incident, but it is quite remarkable. I think we have a slide for one of the flyers from the Change the Status Crow. Down South they’re telling you we don’t want you here. Up North, we believe in the neighborhood concept. Basically, if you’re not in this neighborhood that’s how we’re going to keep you out, we’re going to control who gets to be in this neighborhood. It’s a way in which people who are . . . it’s the NAACP and its CORE, and it’s people like Reverend Milton Galamison. It’s like names and faces that we know from the Civil Rights Movement who are really doing an incredible thing by getting so many people to stay home from school.

There are actually two boycotts. This is the second one in March, and I believe it’s the second one in which Malcolm X also shows up and participates. This is just an incredible moment. Again, the New York Times — and I think we have a slide for their editorial boycott — solves nothing. Their approach to the whole thing is like, “Well, you’re just encouraging truancy. What are you really going to accomplish?” All these people all want too much too fast. This is really their demand. The very last line they’re demanding the impossible. None of this is new; we’ve been hearing this over and over again when it comes to trying to think about what’s a way to create equitable schooling and resources. Jeanne just added that they call the boycott violent.

Hagopian: Wow!

Jones: Yeah, it’s wild. It’s really wild. I should note there’s a big community of people who have contributed to this New York City Civil Rights History Project. One of them, Francine Almash, helped us point out the connection that Milton Galamison actually led in 1965, another boycott that’s aimed at getting justice for disabled students. I think we have a slide for that as well. So, the more you drill down into this history, the more you keep seeing connections across these different histories, and they’re often interrelated. So here, once again, the same person is actually shifting focus and saying, “Wait a minute, we have to do something about what’s happening with students who are being labeled as disabled in various ways. We have to have what? What about them? We have to have a boycott for them.” So that’s 1965.

Hagopian: This is an amazing history and I love the way you started at the beginning talking about how engaging it is for students to learn about students’ struggle, how students have transformed their own education in the past. I’ve seen that in my own classroom and I think a lot of this history is going to be engaging to students. In that vein, I wanted us to be able to talk about some of the current struggles as well. Again, going back to our friend Jeanne’s book, A More Beautiful and Terrible History, she writes, quote, “the history we get is a fable distorting and obscuring the truth. What has become the national story of the Civil Rights Movement provides ways of understanding the past that have political uses in the present.” That just helped me think about what’s going on today. I was hoping you could talk more about why the wealthy and the powerful today are so concerned with outlawing honest history, with not allowing teachers to teach about these histories that you have laid out for us today about systemic racism and social movements.

Jones: Well, I think once you start pulling at this thread and thinking about the other mechanisms of segregation and maintaining inequality — besides saying no negroes allowed on the front of the school door — once you start looking at it in the North and expanding your view, then I think it raises very pointed questions, as you just alluded to, to the all the ways that segregation, including racial segregation and inequality, persist in the present. The stakes of the history are people who don’t want somebody to understand what’s happened in the past are usually people who want to continue doing that very same thing in the present. They don’t want to look at the foundation because they don’t want to fix it if something’s busted in the foundation.

I had the incredible privilege of being on a panel with Khalil Muhammad, a former historian and former director of the Schomburg Center, the other day talking about this very same thing. What’s motivating these book bans and these curriculum bands? He made a revealing point which I’m sure somebody on this channel has probably made before. But I will say it again because it seems so compelling to me. He said, “I think these groups, the most powerful people who are trying to fund and support these bans, don’t really care what we’re teaching at the Schomburg Center. They don’t really care what’s happening in all-Black or majority Black schools. The problem is what happened in the 2020 Uprising, when a whole lot of other people hit the streets, and the words on their lips were Black Lives Matter and a lot of non-Black people were united.

Just think about how remarkable that is that the largest youth awakening and radicalization that we’ve seen in our lifetime happened under the slogan Black Lives Matter. In other words, their anxiety was that their kids, especially white kids, were starting to wake up and ask questions and examine the myths that Jeanne is talking about, and that these book bans are really aimed less at Harlem than they are at Boise, Idaho. They’re aimed at places where there are not a lot of us. But they’re worried about the underlying myths of the nation being troubled.

Hagopian: I know it scared him badly, too. You can always tell a scared racist — they just want to ban what you have to say rather than debate. They know they won’t win on that level.

Jones: Another point worth making is that working with some young people on this New York City Civil Rights History Project, they reported that they too got push back when they asked their teachers in New York City. I think it’s an important caveat to just say, “It’s not just Moms for Liberty.” Actually, it’s the same analysis, it’s not just Southern, that actually in a place like New York City, we too have to do some work to try to make space for these histories. And often young people here will go through and take all the advanced coursework and feel like they really are studying deeply in history, and they never hear these stories at all.

Hagopian: No doubt. Well, that gets me to my last question before the break. I was hoping you could say more about one place that students can learn about the Civil Rights Movement in New York, the New York City Civil Rights History Project. Can you tell us what it is and how to access it?

Jones: It actually is a story of a website and a resource that itself emerged out of this struggle. A group called Teens Take Charge and others were vigorously a few years back challenging then Mayor de Blasio over the persistence of school segregation. They were really following the mayor everywhere, bird dogging. They just would not let it go. They came to Jeanne’s work and started learning that the biggest civil rights protest was in our city on this same issue that we care about, and we never learned this history. So they talked with Jeanne about this, and then I think at some point then Jeanne started tapping friends to come in and participate, including Ansley Erickson, at Teachers College, and me (I was then at the Schomburg Center), and then Jessica Murray, a scholar at CUNY, who has been focused on disability rights. We got a grant from the National Archives and Records Administration to basically build a primary source based resource that would be online for educators, students, learners of all ages and types to try to get their heads around these histories. And it goes way back — there’s timelines and videos and interactive features. But it’s primary source-based, focused on civil rights struggles related to schooling, with these twin areas of focus — the racial justice struggle led by Black and brown parents and students and educators and disability justice.

Hagopian: Excellent. What a great first half of the discussion.

[breakout rooms]

Hagopian: Welcome back, everybody. I hope you had a great, rich discussion. We’d love to hear what you discussed in your breakout room. Please share in the chat, shout out your group, share highlights from your group discussion. We would love to know what you all discussed.

So, one way to support teachers in bringing this history to the classroom is with our Teaching for Black Lives study groups that we have all over the country. We have more than 100 this year. You can see some of their locations on the map, and many members and leaders of those groups are in the session with us today. The applications are now open for study groups for next year, so if you would like to participate in a study group please get at us. We would love to add you. I’d like to invite Sharae Green, a 7th and 8th grade special education and English teacher to tell us about her experience hosting a Teaching for Black Lives study group last year. Can you tell us where you are based and how many people participated in your group?

Sharae Green (she/her): Yes, thanks for having me. First, my name is Sherae Green and I am based in Elk Grove, California, and there were 11 people in our group last year.

Hagopian: Right on. That’s excellent. What have been some of the biggest benefits to your group of hosting a Teaching for Black Lives study group?

Green: The biggest benefit is the affirming validation of meeting together to discuss our Black students, and the feeling of knowing how urgent and necessary the readings and conversations are. As we continue to read stories from the Teaching for Black Lives book one of the things that kept coming up for us is creating actionable steps from our discussions. Through this group it gave us the knowledge and confidence we needed to begin the Black Lives Matter Week of Action at our school. It was something we had never heard of before and it became a schoolwide thing.

Additionally, at the end of the school year I put forward a class recommendation to an introduction to Black African American studies and culture, which I’m certain will get approved this year. I’m really going to push for that, and I’ll be able to teach it next year. Also, I feel like this group gave us additional fortitude and resolve and the extra boost we needed, because oftentimes fighting for our humanity and the humanity of our students, it can be exhausting. And knowing others around the country were fighting with us and being able to come together online and see it, it’s really powerful. There’s just so much work to be done, and knowing that we’re not alone is priceless. This group says to us, “Yes, we are going to directly take action towards improving Black lives within our schools and districts and across the country.”

Hagopian: Great. Thank you so much for sharing your experience there. It is really inspiring to hear from you and your group, and just to think about the hundreds and thousands of teachers doing this study group every year who are transforming public education, not only in your own classroom, but the way you were talking about organizing for the Black Lives Matter Week of Action. Joining this national network and movement around demands to transform education is just so powerful and I hope others here today will consider your example and be inspired by it to start their own study group. So, thanks for sharing your story.

Green: Yeah, thank you for allowing me to speak today, and I appreciate the work that you all are doing.

Hagopian: Right on. Take care! Welcome back, Brian. That was cool, right?

Jones: That was amazing. Wow! That gave me a boost.

Hagopian: Good. I’m glad you got to hear about that struggle. So, let me ask you a couple more questions before we wrap up this evening. I was hoping you could help us get a sense of what these struggles looked like outside of New York in terms of the Civil Rights Movement of the North. Can you share some other Northern school movements nationally?

Jones: As I mentioned before, 1964 was really a high watermark for these kinds of struggles, of protests led by Black families and students fighting against segregated and unequal schooling in the North. Some 20,000 students, in 1964, boycotted the schools in Gary, Indiana. More than 75,000 did in Cleveland, Ohio, [They] just go on and on.

A book I was reading recently, which I want to highly recommend is by Elizabeth Todd-Breland — A Political Education is the title — for anybody who is inspired by Karen Lewis in the early 2000s or first decades of the 2000s social justice activism of the Chicago Teachers Union. Karen Lewis has since passed, unfortunately, but was a Black woman who was the leader of that union through one of the most inspiring strikes I think we’ve seen in teacher union activism in a while, and one that very squarely called out segregation and inequality. I mean, they called the Chicago schools an apartheid system. So that was an amazing moment. And in doing so won a lot of support from Black parents and communities in solidarity with the educators on strike. But what Elizabeth Todd-Breland does in this book is go back through history and actually show that that strike didn’t come out of nowhere, that actually Black parents and educators and students have been organizing. She really focuses on the role of Black women, which in many of our civil rights histories are undertold stories. But in this history she brings their stories through to the fore.

One thing that she brings out is that the year before the big half a million people boycotted New York City, in October 1963, 225 students boycotted the Chicago schools, just like New York. It’s almost half, and for the same reasons that they’re segregated and unequal. We could repeat the stories all over the North and the West. Just one more thing to say is that all of these big moments of protest, all of them, too, have a history of people organizing, and organizing it looks a lot of different ways. Sometimes they’re sitting on very official city commissions where somebody says, “Sure, fine, Ella Baker, tell us what you think about the schools, and go to all the meetings. Whatever.” People participate and then they try to say it as plainly as they can, but if they don’t get satisfaction then they have to go a step further and go a step further. And that’s how you get to a point where half of the students in a city are boycotting in a place like Chicago or New York. So I think all of these are real movements that build over time.

Hagopian: I recently learned about the Seattle school boycott that happened around the same time as what happened in New York and Chicago, and all over. It was really a national movement of Black youth and families highlighting what it called Jim Crow.

Jones: Status Crow.

Hagopian: Status Crowism in Northern schools. Yes, amazing! Well, I wanted to discuss the fact that this year marks the 70th anniversary of the Brown v. Board of Education decision, which is really misunderstood, and textbooks often get it wrong. So I wanted to talk with you and help educators here get it right. That was the court decision that ruled that segregated schooling was illegal. I recently read a quote from Bettina Love about it. She said this quote: “Nationwide data from the fall of 2022 shows that 75% of white students in America went to majority white public schools. School integration is no longer moving at a slow pace. It is in reverse motion, with all deliberate speed because Brown continues to be gutted legislatively, locally, and at the school level.” So I was hoping you could talk about the history and legacy of school segregation and desegregation in the North and help us make sense of Brown v. Board.

Jones: Yeah, how much time you got?

Well, I’m actually trying to write about this for the second book, so stay tuned. But let me just say a few thoughts. This is a big conversation, and I think one of the things I’ve been trying to do is unlearn for myself the way I’ve absorbed the ideas of Brown as the landmark moment of justice in education. There’s so many reasons why I think we have to figure out a way to both hold the importance of the moment, but also see its limitations and its problems.

One thing I’ve been trying to read about and understand more is what happened to Black educators afterwards? People like Vanessa Siddle Walker and many others have been trying to teach us about the history of Black education during the long eras of segregation. I think what she and others have tried to show us is that when the moment of desegregation came and Brown v. Board came down, a lot of Black educators were worried because they saw what was coming. In many places they drew up plans to try to say, “Okay, we’re going to desegregate. How’s that going to go? Well, a logical thing is that some of us should go over there to those schools because we know the kids. So logically, some of us should go with them to that school, and some of your teachers, some of your principals, should come over here because we’re going to accept some of your students, and you should send some adults over.”

In other words, this should all be done on the basis of equality and with power shared among us, where we’re part of making decisions together about how this is all going to go down. But of course we know none of that is how this went down, and people like Ansley Erickson have written about the way desegregation actually went down was that in almost every case it was local white people who were in charge of how it was going to go down. They did not share power or take into consideration or think about what Black parents or educators wanted or felt. In too many cases they designed it to be that some Black students would go to a white school, and never the reverse. And Black schools by implication were inferior, by definition inferior. Even the most widely celebrated, the most successful with brilliant PhDs teaching were all considered by definition, failure. So that’s one of the consequences of desegregation which didn’t have to be. But the way it was felt and was experienced was a tremendous loss for people. Some 30,000, maybe more, Black teachers lost their jobs. Some 2,000 or more Black principals lost their jobs. This was a massacre of Black educators. Think of the role of Black educators, the long struggles for learning and liberation.

Jim Crow’s Pink Slip by Leslie Fenwick is a really powerful book that really goes through this in gory detail. I also want to shout out Jon Hale’s book A New Kind of Youth, which, although it’s focused on Southern Black high schools, eventually shows how it becomes a national story. If you think about it, it was Black high schools with Black educators that really set the 20th century on fire. That was like the incubator for what became these powerful movements that changed the nation. Later in the 20th century, what they did was these Black students suddenly are in white spaces without any of the adults who know them, and every action they take to try to get justice for themselves, to try to change the curriculum, to try to speak up, they get criminalized. You have this tripartite attack. You’re attacking the Black schools and shutting them down; you’re firing the Black educators; and then you’re criminalizing the Black students. That legacy is still with us today in all of the zero tolerance stuff. It has been a tragedy, and it really did not have to be that way. We have a lot to reckon with when it comes to trying to think about what it is going to take to undo and unwind the ways that we’ve enshrined inequality and segregation in our schools.

Hagopian: Brian, what a brilliant conversation! Thank you so much for your time. I can’t wait to invite you back when your new book comes out and discuss all of these topics in more depth.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect, please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

Here are many of the lessons, books, and other resources recommended by the presenters and participants:

Lessons and Curricula

|

“Intolerable Conditions”: Teaching About Northern Racism Through Rosa Parks’s Detroit by Say Burgin, Jeanne Theoharis, and Ursula Wolfe-Rocca “A School Year Like No Other”: Eyes on the Prize: “Fighting Back: 1957-1962” by Bill Bigelow The Largest Civil Rights Protest You’ve Never Heard Of: Teaching the 1964 New York City School Boycott by Adam Sanchez (Rethinking Schools) How Red Lines Built White Wealth: A Lesson on Housing Segregation in the 20th Century by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca What We Don’t Learn About the Black Panther Party — but Should by Adam Sanchez and Jesse Hagopian ‘What We Want, What We Believe’: Teaching with the Black Panthers’ 10-Point Program by Wayne Au Why I Teach Look for Me in the Whirlwind by T.J. Whitaker (Rethinking Schools) Teaching for Black Lives edited by Dyan Watson, Jesse Hagopian, Wayne Au (Rethinking Schools) |

Books

|

Educating Harlem: A Century of Schooling and Resistance in a Black Community edited by Ansley T. Erickson and Ernest Morrell The Strange Careers of the Jim Crow North: Segregation and Struggle Outside of the South edited by Brian Purnell and Jeanne Theoharis with Komozi Woodard A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History by Jeanne Theoharis The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks: Young Readers Edition by Jeanne Theoharis and Brandy Colbert The Rock and the River by Kekla Magoon Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad by Matthew Delmont Jim Crow’s Pink Slip: The Untold Story of Black Principal and Teacher Leadership by Leslie T. Fenwick A Political Education: Black Politics and Education Reform in Chicago since the 1960s by Elizabeth Todd-Breland |

New York City Civil Rights History Project

| New York City Civil Rights History Project is a digital history of educational activism in NYC through collections of archival documents, photographs, videos, oral history snippets, and more. Primary sources highlighted during the class: |

This Day In History

The dates below come from our This Day in People’s History collection, which contains hundreds of entries all searchable by date, state, theme, and keywords.

|

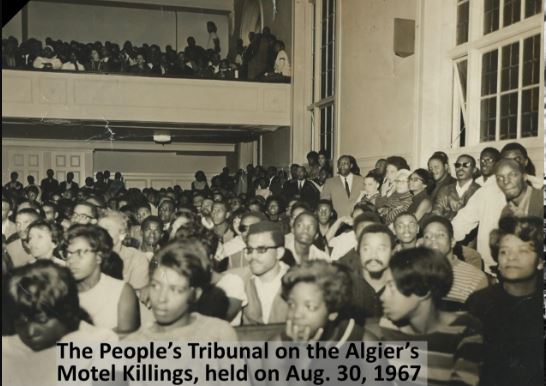

Oct. 22, 1963: Chicago School Boycott Feb. 3, 1964: New York City School Children Boycott School June 11, 1965: Chicago School Boycott Oct. 15, 1966: The Black Panther Party Founded Aug. 30, 1967: People’s Tribunal in Detroit April 23, 1968: Columbia Student Occupation May 9, 1968: Ocean Hill-Brownsville Teachers’ Strike of 1968 Sept. 16, 1968: Harrison High School Student Uprising April 22, 1969: Student Strike Shuts Down City College of New York July 14, 1970: Young Lords Occupy Lincoln Hospital |

Participant Reflections

With more than 240 attendees present, the conversation and chat was lively, engaging, and full of history, teaching ideas, and more. Polls showed participants included 43 percent K–12 teachers, 19 percent teacher educators, 5 percent K–12 students, and many more.

Here are more comments that participants shared in their end-of-session evaluation:

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

That the largest protest of the Civil Rights Movement was in NYC and that it was a fight over segregated schools!

All the primary sources I can add to my lessons; also the idea of comparing a New York Times article for a certain day to how an event was covered in a Black newspaper. Cannot believe I never thought of that. . . it’s so simple but brilliant!

The implications of dividing the Civil Rights movement geographically, and how activism can’t be contained to just one area of the country. The ending question about Brown v. Board was incredibly eye-opening; I knew that the case was harmful for Black schools and educators, but Brian Jones’ response really opened my eyes to the extent of the damage and control white leaders had over desegregation.

Segregation continues to be an unresolved national problem.

One thing that really resonated with me was the idea that the struggle for disability justice is tied to the struggle for racial justice.

De facto vs. de jure segregation and its impact on schools and communities.

The resistance to segregation in the North and how Status Crow-ism in Northern schools operated.

One of the most important things I learned today is that NYC barred segregation in schools in 1823. Yet, we still experience it. Through time, there are titles and acts and legislation that has ambiguous wording and expectations, which result in further segregation and inequity.

Something I never realized about Brown v. Board of Education — I never knew how many Black teachers lost their jobs. I also never stopped to think about how those in position of power (white men) were making all of the decisions and how that instilled this idea that Black schools are “inferior.”

The idea of documenting and sharing with students how segregation and racial discrimination looked in the town where they live.

The founding of the Black Panther Party in NYC was connected to school discrimination. Wow!

This session was a great reminder to remain critical of all sides of a story. Too often the North is given a pass for its role in enslavement, segregation, and discrimination. It is extremely important to see this country not as North and South, but more so how the North and South have worked together to achieve goals that most often failed to be inclusive or equitable.

What will you do with what you learned?

I will use this to augment my department’s lessons on school desegregation in the North — we look at Boston (because it is a local story) but this will help expand our narrative.

Immediately share resources with my students, one of whom is writing on this topic as we speak!

I will be intentional about 1) selecting locations that represent many areas of the United States, 2) I will broaden my use of artifacts and primary sources, and 3) I will have students bring in their personal stories of their neighborhoods and schools.

I teach future elementary teachers in Michigan and I’ve always wanted to do lessons around Northern racism, but as an Alabamian I never felt like I knew enough, let alone where to start. I need to think more about how to actually do that, but I feel empowered to do so and I’m excited!!!

The primary documents were excellent and I can’t wait to use them.

I plan to utilize the various newspaper sources to get students to see the stories that are told versus the ones that are not (or are reported differently). I plan to educate myself further on the protests/boycotts centered around schools.

I am invested in thinking more specifically and taking action around the ongoing mechanisms of segregation and injustice in our schools and our cities. Our institutions continue to maintain segregated schools with inequitable outcomes.

Although I’m a teacher in Texas and was raised in the D.C. metro area, I will use this information to demonstrate how much we must unlearn about the Civil Rights Movement. We tend to hone in on the traditionally accepted timelines, people, and events. I’d like to incorporate more information that isn’t as well known but will allow my students to see how we’re all connected.

I would love to incorporate the idea of comparing primary sources to the NYT headlines. I think this would be such a great way to teach my 6th grade students and show them to view information with a critical eye. Great suggestion!

Continue my abolitionist decolonization teaching practices with renewed passion.

I will be turnkeying with my department as well as revising my units of study.

This class reinforces for me how important it is for my students to also learn the missing history and realize how powerful and important their voices are.

How was the format for the class?

Good format; just enough interaction.

I love, love, love the breakout groups!

Thank you for always doing such a great job with these sessions! They are amazing opportunities for authentic learning that provide tangible resources.

Everything worked beautifully, and such a great presentation and discussion!

I really enjoyed the breakout groups. I like that Brian included images and primary sources in his presentation.

I love the format because the short breakout rooms allow just enough to share and get back to the large group discussion.

I loved the conversation in our breakout room — we could’ve talked for hours! The format was wonderful as always. Thank you for all that you do to make this available and possible for us.

Presenters

Brian Jones is the inaugural director of the Center for Educators and Schools of the New York Public Library, and formerly the associate director of Education at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Jones was an elementary school teacher for nine years and earned a PhD in Urban Education at the CUNY Graduate Center. He has contributed to numerous publications, including Black Lives Matter At School: An Uprising for Educational Justice and is the author of The Tuskegee Student Uprising: A History.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing, author of Teach Truth: The Struggle for Antiracist Education, and serves on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn