On June 19, the weekly People’s Historians Online mini-class featured a conversation between Greg Carr and Jessica Rucker about Reconstruction and Juneteenth.

On June 19, the weekly People’s Historians Online mini-class featured a conversation between Greg Carr and Jessica Rucker about Reconstruction and Juneteenth.

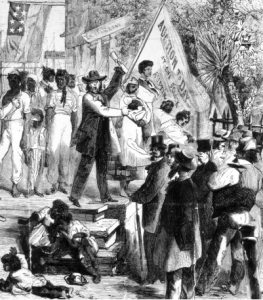

The session addressed themes of our campaigns to Teach Reconstruction and to teach about voting rights on this 150th anniversary year of the 15th Amendment and an election year. Here are just a few reflections from participants on what they learned. (More reflections at the end of this page.)

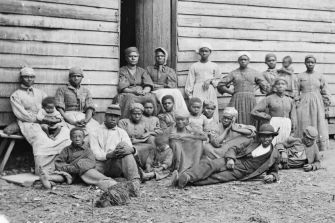

The concept of how formerly enslaved people were FREED but not FREE, and how we question the idea of Reconstruction because it was a new FOUNDING, and we’re in a third phase of that right now. I also appreciated references to other past movements when discussing today’s moment of anti-police brutality/white supremacy, and what our role as educators is.

The idea that we are in a 3rd Reconstruction or Founding. This notion helps me brainstorm a the theme for my social studies classes next school year looking at citizenship and our role in contributing to the reality of a global citizenship.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jessica Rucker: My name is Jessica Rucker, and I’m in Washington D.C. I’d like to say hello to everyone here on behalf of the Zinn Education Project for our session on Reconstruction and Juneteenth. Some of you are joining us for the first time, and some of you participated in one or each of our sessions over the past several weeks. So, welcome and welcome back. I’m a high school teacher and I regularly use lessons from the Zinn Education Project, which is coordinated by Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change. I love their resources, both online and some of their prep materials. The Zinn Education Project is hosting this session today as a part of the Teach Reconstruction Campaign. The Zinn Education Project offers free downloadable people’s history lessons that many of you have used for middle and high school classrooms, from the Zinn Education Project website.

Before I begin my conversation with Dr. Greg Carr — and that’ll be the last time you hear me call him Dr. Greg Carr — we want to find out who’s in the room and go through our plans for our time together. So, if you would, please go ahead and rep yourself. How many teachers, librarians, teacher educators, historians, parents, students, labor or community organizers, or other folks in the room? Wow, 52% of us are educators, 14% are students, 2% are family members or caregivers, 2% are librarians, 8% are historians, 12% teacher educators, 3% labor or community organizers, and 9% of us are others. Alright, welcome, welcome. We are ready to start our conversation. Throughout the session, we want you to use the chat box to post questions, comments, resources, ideas, [and] our guest speaker and I are going to read your questions and try to respond after the breakout groups. So, make sure to return and then we’re going to do a short evaluation at the end. After about 20 minutes, we’re going to pause so that you can meet each other and talk in small groups to share insights.

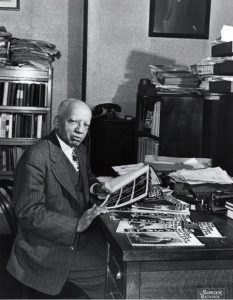

I’m happy to introduce Greg Carr, associate professor of Africana Studies, chair of the Department of Afro American Studies at Howard University, which is just right down the street from me, and adjunct faculty at the Howard University School of Law. Carr is the founder of the Philadelphia Freedom Schools Movement and is an advisor for the Zinn Education Project’s Teach Reconstruction Campaign. So, brother Greg, let’s start this conversation. June 19, like some of my favorite MCs, has many names: it’s Juneteenth, Freedom Day, Jubilee Day, even Celebration Day. What’s the significance of June 19 and why does it have so many names?

Greg Carr: Well, first of all, thank you Jessica, for not only being in conversation with me today, but for being an integral part of the Zinn Education Project work. First and foremost, as John Clarke, my old teacher, used to say, “All I ever wanted to be was a great classroom teacher.” I want to pay you respect, because I’ve seen you in action. Thank you for your work as a teacher, and by extension, every teacher in this conversation, polls notwithstanding — I’m assuming everybody on here has a teaching role and function.

Juneteenth, which apparently now is a national thing in the wake of this latest general strike against the social order, is one of the many emancipation rituals that people of African descent have created over the last century and a half. It’s interesting because those rituals were created by African people. We know some of them. I mean, many people want to call know and have celebrated January 1, which is when the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect in 1863. But, as many of you on the call know, particularly those of y’all who grew up in the north, the churches in the north — Boston, Philadelphia, New York — many of those churches, they prayed on the last day of December 1862, and brought in the new year with the expectation that now it was time to get up off our knees and go get some guns and support those with guns and make this Emancipation Proclamation stand up, since it didn’t apply unless you were in control of the place that you went to battle. It’s one of the origins of Watch Night.

I remember an exhibition, and a couple people on the line who worked with the museum, the Smithsonian, there was an exhibit at the Museum of American History, a temporary exhibit over there on the second floor, and they had a quote from Silas Xavier Floyd, a minister. Of course, January 1 was the Celebration Day for a lot of Black people for years because of the Emancipation, and the quote from Silas Floyd said, “May God forget my people, if we forget this day,” and that was January 1, not June 19. That’s just one of many examples.

You mentioned Decoration Day. Of course, we think about the roots of what became Memorial Day, the idea of honoring our ancestors who made the ultimate sacrifice by placing flowers on their graves. Coming out of South Carolina, it reminds me of the gospel army. There’s a very good book called Conjuring Freedom that talks about that South Carolina regiment of colored troops. That beautiful Ed Dwight monument is on the South Carolina state house grounds. We talked about the Confederate flag that came off the dome, but if you ever go down to Columbia, go see Ed Dwight because you see the Gospel Army marching in. And Decoration Day comes out of that. Then, of course, that’s one of the roots of Memorial Day.

Finally — and I’ll wrap this up, because there’s so many different celebrations — what we see in Galveston, Texas in 1865, has a lot to do with, in fact, it’s connected also to the Caribbean. If we look at Jeffrey R. Kerr-Ritchie, he wrote Rights of August First, he’s in history at Howard University, wrote a whole book on Emancipation Day celebrations in the Caribbean called Rights of August First, for anybody on this call or in the conversation from the Caribbean. Then, in July and August, it’s Emancipation Day in Trinidad, Jamaica, and other places.

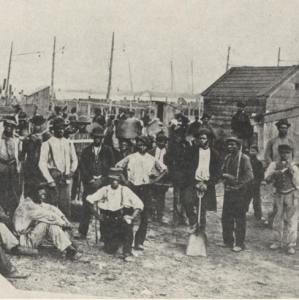

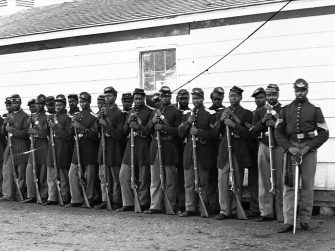

I should say one other thing. We know Frederick Douglass gave them “What, to the Slave, is the Fourth of July.” He gave it in New York at Corinthian Hall on the 5th of July, because Black people and abolitionists said the fourth doesn’t mean anything to us, so we’ll wait until the fifth and critique the fourth. So even that becomes a day. But in Galveston, when General Granger marched into Galveston with those troops, the interesting thing is — and here I want to pause for a split second. James Morgan is on the call. He works with the African American History Museum and gives respect to an ancestor who was really without price. This was a true brother, a great minded historian, and that’s the great Harry Jones. Harry Jones always reminds us that, while on June 19, General Granger read the Emancipation Proclamation off that veranda in Galveston and Blacks were like “Okay, we free!,” Harry Jones reminds us that there were at least nine regiments of the United States Colored Troops making their way through Texas. Texas, the last of the ten states in the Confederacy to give up. Texas, then and now, the idea that they’re independent, the Lone Star state, although the Juneteenth flag explodes that star between that red and blue field. Texas says we’re not giving up, but Black troops, some of those same Black troops that have captured Richmond, those Black troops were now in Texas. So, while Granger makes the formal announcement on June 19, and then a year later to the day Black folks start celebrating Juneteenth formally, those Black troops are spreading the word with every marching foot as they come across the south.

So June 19 is the official day marking these emancipation celebrations as it comes into the African awareness formerly in Texas, but the dates are usually linked to whenever people found out they were free, which is why Mississippi, places in Alabama, places in Arkansas, Oklahoma, you might see an August date or a July date. We’ll talk, in fact, I mentioned this, and keep going. This is William Wiggins, his book called O Freedom: Afro-American Emancipation Celebrations. Wiggins wrote a two volume dissertation, about 500 pages. This book is only 200 pages, because 300 of these pages are in his dissertation, which are just transcripts of old heads that he interviewed in the 1970s that talk about the Juneteenth celebrations, and then and there, that’s where you see the date changes, depending on when people found out in Mississippi, in Arkansas, in Alabama, places like that.

Rucker: Wow, the dates that people found out they were free. Some people are finding this out today, and that’s okay. We’re going to love up on them, too. So, let’s jump into another poll, real quick. Speaking of which, with regard to Juneteenth, we want you to check off as many of these statements that apply as possible: You learned about this history in middle or high school; you didn’t learn about it in middle or high school; you teach about this history because you’re a teacher in middle or high school; you teach your children; or, you don’t teach about this yet, but you are here to learn.

I love seeing the numbers tallying. So, we’re going to kick off the second question. Let’s stick with June 19, 1865. That’s 155 years ago today. Give us a little context for what social relationships were like in the U.S., because you were getting there leading up to June 19. Help us understand what elements of those social relationships have carried over to 2020, which have not, and why.

Carr: Excellent. Very quickly, I’ll recommend another text, which is Katherine Franke’s book Repair. My friend, Katherine Franke, I’m sure there are people on the call who know this sister. She’s at the Center for Constitutional Rights in New York, also at Columbia University. Katherine Franke’s book Repair talks about how, well, I’ll come back to in a second.

The field of originary violence, of course, is set with the invasion of this continent. So, with all due respect to folks who say the original sin of America is the enslavement of African people, if we’re going to talk in the context of sin and redemption, we should probably say the Original Sin is the dispossession of the Aboriginals, the natives of this land. That field of violence just continues to spread, and as Africans are brought into that theater of violence as property, the resistance to that field of violence also has its markings. The social relations in American society have always been hierarchical, if we’re going to go back just to the colonial moment, meaning there’s always going to be somebody on top. Whether it’s Toni Morrison writing about, among other things, why folks who are elites have to negotiate their way, whether it’s John Adams during the American Revolution, people before the revolution, a third were against it. And a third didn’t care. There’s ambivalences in white society. But what allows whiteness to emerge, of course, is that it is constructed against something else, namely non-whiteness. At the bottom of that hierarchy is Blackness. So Black-white social relations are always going to be unequal in this society. Meanwhile, who are these Africans?

One thing we must always do — and of course, this is nothing new to all educators on this call — is ask different questions. So, the first question we always want to ask when we’re talking about Black people is, “Who are they to each other?” Then we asked, “Who are they to other people?” So, the social structure question, or who are they to the other people, defines the social relations outside of Black communities. But within Black communities, you find Black folks want freedom, they want liberation. They’re going to negotiate with whoever they need to to be able to preserve some sense of freedom. Or as Robin Kelley, who also presented in this series, will call it, “freedom dreams.” But, within that Black community there’s a sense that we will maintain our humanity one way or the other.

Now, let me fast forward very quickly because I know we don’t have a lot of time today. The social relations, by the time you get into Civil War, of course, you’ve got forty million or so Africans, mostly enslaved, in the South in this country. You’ve got a handful of Blacks outside the South, the Black abolitionists joining the white abolitionists, and others trying to smash enslavement.

By the way, I’m noticing these texts noting that Watch Night was also known as Freedom’s Eve. I like that; maybe we can get Freedom’s Eve on the last day of December as a national holiday, as well.

So, there’s this move to smash the slave power, so to speak, in the South as the war jumps off, out of Fort Sumter in 1860. As the Union wins battles, they’ve got to decide what we want to do about these Africans. Why? Because they’re freeing themselves. So they pass these contraband acts; the first contraband act, second contraband act, now we’re into 1862, 1863. That’s where Katherine Franke picks up in Repair. And she’s following in the echo of this brother, as well, the great Vincent Harding, who wrote There is a River. This brother talks about the fact that when you get to South Carolina, they ask these Africans, “Will y’all keep growing cotton for us, the Union, because we need this money to fund the war effort?” But these Negroes smash a lot of the cotton gins and say, “No more picking.” So, they have to negotiate with them. One of the things they offer them as an incentive is [they say] if you will stay here, we’ll give you first dibs on the land, we’ll help you get this land. This also happens as far west as Mississippi. Jefferson Davis’s brother Ben had a plantation that Black people ran, and when he ran off the Union came in and tried to make a similar deal with those Africans. So, the social relations by the time of the Civil War, everything’s contested and everybody’s negotiating.

By the time Granger gets to the Gulf, you’ve got to negotiate with these Black folks because, guess what, who are they to each other? They’re human beings. So, a guy like Jack Yates, born in Virginia, comes all the way across the continent to Texas, and, in 1872, this formerly enslaved African and two other people put money down and buy Emancipation Park in Houston, which is still there today for the express purpose of celebrating Juneteenth. Jack Yates, by the way, is the name of the high school George Floyd went to. So, understand that all of this comes from a spirit of self determination.

The social relations between Blacks and non-Blacks, particularly white elites, is going to be fraught with tensions. There’s a hierarchy; the same one we’re trying to overthrow right now, between the poor whites and the Blacks. Those poor whites who have sense enough to know that whiteness has no value, and therefore you need to make common cause with us. These are the white people on the border. In fact, this is one of my prized possessions, Doris Hollis Pemberton’s Juneteenth at Comanche Crossing. This is one of the oldest Juneteenth celebrations, down there near Galveston. You hear white people celebrating Juneteenth. “Why, I ain’t got no money, I ain’t got no beef. I’m with y’all.” But those people have a different type of social relation. I mean, the tension.

In conclusion, that same night, nine regiments of the U.S. Colored Troops came to help chase the Confederates out of Texas. A bunch of the Confederates went over the Rio Grande into Texas. And that happened right before Granger shows up to read the proclamation. Well, guess what? Mexico had abolished enslavement. As we see at the Zinn Education Project, when you look on the ZEP site, you’ll find something about the origins of Cinco de Mayo, the Mexicans weren’t for that slavery. So, all the relations, really are just a beautiful tapestry of human resistance to oppression. I went on too far, but now we’ve got further to go. And you know the story.

Rucker: The last story you just taught, this book It’s Bigger Than Hip Hop by M. K. Asante, Jr., my students love the section on solidarity when they find that the government of Mexico opened up its borders. He was like, “Yo come through.” I’m like, “Wow, they look at each other like, we been here for each other.”

We’re going to publish this poll real quick. These are the results: 7% of us learned about this history in middle school; 78% of us did not learn about this history in middle or high school; 22% of us teach about this currently; 17% of folks teach this at home; and 44% don’t teach it yet, but they are here to learn and they are taking notes.

We’re going to keep this conversation going, just like the movement.

Carr: I wanted to mention one other source, Gerald Horne’s Black and Brown: African Americans and the Mexican Revolution, 1910-1920. He started in 1910, but he goes back before then to underscore the point you’re raising — and that M. K. Asante raises in It’s Bigger Than Hip Hop. Which, parenthetically for y’all, just so y’all know what kind of teacher Jessica is, she brought this whole group of her high school students up to Howard, and we had so much fun with Asante. We had so much fun with your students, Jessica. I’m just mad now that we are talking into computers [rather than us] all together physically. I cannot wait for you to bring some more students up, because y’all read that book in ways that I’m sure even M. K. Asanti hadn’t anticipated.

Rucker: You’re too kind, brother Greg. This notion of the original sin, I want to go back to something you were saying about honoring and commemorating Juneteenth in the context of really reconceptualizing what we’re doing today to displace this notion of citizenship as a prerequisite for full social equity. And that’s coming from your words, on Twitter.

Carr: That’s the challenge, right? I mean, we were talking yesterday, those of you who have heard Ursula on a lot of these calls and all these presentations, one of the things Ursula was talking about was this question of rethinking concepts. How do we change the narrative? How do we ask different kinds of questions? I got so inspired, I was sitting here taking notes, you know, how do we jailbreak chronology? How do we deal with these things? And by the way, if you’re on this call and you were at the Museum of African American History and Culture last fall when the 1619 Project was brought there and had conversations, let me do two things. Number one: I’m glad you all were there. I’m glad your students were there. Let me apologize, because in a split second, if I had just paused, I would have stopped and asked every teacher in that building to stand up because we know that, if not for you all, these young people wouldn’t be armed with the content to do the kind of critical thinking they’re doing. So, I wanted to say that.

But, during that session last fall at the museum, we got into a little bit of a back and forth, had a little conversation with Eric Foner, the brilliant scholar of Reconstruction, 19th century history, African American economic history. His book had just come out, The Second Founding, and I thought it was fitting. We’ll talk about that in a second. But, one of the things we got into a little conversation about was the Reconstruction Constitution Amendments 13, 14, and 15. The question of citizenship really becomes the coin of the realm for humanity in the modern nation state. Meaning if you’re a citizen, you are a full human being. If you’re not a citizen, you’ve got to be looking over your shoulder. Why do you have to be looking over your shoulder in the modern world? Are you breathing? Yeah. Did you come out of somebody’s womb? Yeah. Okay, you’re a human being. We shouldn’t be ranking people’s humanity based on their legal relationship to the state. So we didn’t get a chance to get into a lot in that session. But the point I was really trying to raise was, we have to, kind of echoing what Ursula was raising yesterday, we have to rethink everything.

What is so beautiful at this moment in the history of the world, this pandemic is a tragedy, and please, everybody who’s out there who’s got family or friends who have suffered, if you’ve been sick yourself, all the best energies to you. All the treaties to ancestors for your continued health and protection. We know that in the middle of his field of a pandemic, this general strike against the state has unified people in ways that overflowed the boundaries of citizenship. We’ve got folks who won’t go get tested because they’re afraid they’re trying to collect their information. Next thing you know, they’ll put them somewhere and ship them out of the country, or they’ll threaten to do it, or they’ll lock them up. The pandemic has hit these people, essential workers, who, now, when they went to work at Walmart, when they delivered your mail, or when they are on the front lines trying to help people get mass. But, in some ways, the idea of citizenship has been undermined in this moment of pandemic, and people are in the streets, finally.

When the decision that came down, the DACA case that was decided yesterday, when the idea that even these institutions like the Supreme Court of the United States and the federal judiciary, John Roberts did not want to be caught out there standing on the wrong side of history. If you read the decision, the opinion, what you’ll see is he really kind of called a tick. He basically said, “I didn’t say you couldn’t do it, I just said that you really didn’t say ‘Mother may I?’. So, I’m going to let you return this back and come up with a better rationale.” Okay, John, I’ll see you, that was the stated rationale. But what you did not want to do is be on the wrong side of history. I read that as another step in where we ultimately have to come to: we have to rethink the idea of citizenship. If you are a human being in the world, you should be able to walk through this world as free and as connected to everyone as anybody else. And you shouldn’t have a bar between you called citizenship that can somehow constrict your humanity and shrink it to fit some preconceived notion.

Well, I should say, one of the things as it relates to Juneteenth, as Katherine Franke talks about in this book, Repair, after the Emancipation Proclamation, after the end of the war, there’s a period when these Black people and that citizens, but they are not enslaved. Professor Franke uses the word freed with a “d”, but there’s somewhere in between. In 2020 I don’t know that that “d” has been diminished enough to the point where we should remove it. There are a lot of freed people walking around, but citizenship hasn’t been promised to but a handful of people in this country anyway. And executed.

Rucker: Dr. Carr, thank you. You know that that love is mutual. The students really appreciated how you challenge the ideas of what it means to be human. You’re an incredible professor and critical thinker. This notion of freed, this social purgatory that oppressed people have found ourselves in, is very, had been put in not found ourselves in but had been put in, is quite uncomfortable. I’m going to try one more question before we kick it off to the breakout groups. I want us to keep on talking about this notion of humanity, of challenging citizenship, and even in rethinking boundaries of what we call countries or nations and states. So, as we speak right now, there are various protests, rallies, and other forms of direct action taking place across DC, the 50 states, and almost 20 other countries throughout the world, connected to the 2020 uprisings. What should we be learning from this moment, and what should we be teaching about this moment?

Carr: That’s a question that I don’t have a good answer for. In fact, let me close the Foner loop. I was writing something down the other day, and we talked about the first Reconstruction, which is what we’re talking about now. Of course, those of you who have availed yourselves of the brilliant Teach Reconstruction series from ZEP — and Bill Bigelow, who I got a chance to say hello to today, he’s got a couple of pieces on it in Teaching for Black Lives. That’s the first Reconstruction. Now, of course, that one didn’t quite stick.

So, there was a second Reconstruction. Now, William Barber and others, and the third Reconstruction. In fact, the Poor People’s Campaign starts, I think, tomorrow, the virtual version of it. I should pause there to say in June 1968, they assembled on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, and they had something called Solidarity Day DC. And that was deliberately on June 10, to close out the Poor People’s Campaign. At any rate, when we think about this third Reconstruction we’re in, I think the lessons we can learn from the previous two Reconstructions are that — and Jessica, you brought this up, we were talking yesterday, maybe you could say more about this question of responses to Reconstruction, the redemption piece — but, in the wake of this conflict, you try to rebuild society.

Finally, what I think we can learn from this, I want to suggest maybe even another term. We’ve got to rethink these narratives. If we have a first Reconstruction, a second Reconstruction, and a third possible Reconstruction going on when we try to rebuild, how can we rethink the idea that Reconstruction is linked to a previous Reconstruction? I’m thinking about Ishmael Reed and his critique of the Hamilton piece. I won’t go so far as to call Hamilton brownface minstrelsy, yet I guess I did say it.

Anyway, the name of Foner’s book is The Second Founding. I liked it. If you’re coming to first Reconstruction, the second founding, the first one being the Declaration of Independence. I liked that concept. Maybe we can call the second Reconstruction the third founding. Maybe what we’re learning today with this multiracial, intergenerational multiclass wave — the social protest that’s got people doing things they said they couldn’t do a month ago, getting rid of statues, throwing flags in the ocean. They’ve taken down Leopold in Belgium, and they kicked statues into the water in the Thames in London. Is what we’re watching possibly not a Reconstruction, but a founding? Are we possibly on the verge of founding a society rather than reconstructing one? To me, that’s the kind of conversation you have with a bunch of young people who have been brought into an originary field of violence that has a hierarchy they expect those young people to fit in that they don’t want to fit in because they are somebody else to each other. Maybe we change the language to “founding” and see where it takes us in classroom exercise.

Rucker: We want to honor our agreements with the time, so let’s take one more question. I’m on the fence about the nature of the question to ask, but there’s something there about young people. There’s something there about retooling our imaginations, expanding articulation, and being vigilant with our language, since language constructs realities. Tell us a little bit about the role of young people and imagination in movements, or even in this era that’s historically known as Reconstruction.

Carr: I will say this very quickly. These movements always work best when they’re intergenerational. And we think of course about the famous Ella Baker speech, Sweet Honey in the Rock, Bernice Johnson Reagon, and her comrades turned into “Ella’s Song.” Well, you know me, to me, young people come first. They have the courage where we fail. And I think about what Dave Chappelle said last week, when he said, “I’m comfortable in the backseat. These young people got ii; the streets are to talking.” I think those two things work together, in the sense that what is the role of a guide, or an elder, or a teacher? “t isn’t to be our friend.

If you go all the way back to the ancient Egyptians, the position of authority is actually the back position. When you see the stellar in ancient Egypt, if a man dies, you see his stellar, and you see him sitting there getting ready to meet the next iteration of reality. Behind him is his partner. Usually you see her with her hands up behind him. Why? Because I’m still alive, you’re an ancestor, and I’m entreating whatever’s in front of you, to welcome you to that side. Being in the back seat is not a position of surrender. It’s not a position of being off the battlefield. No. Let those young people drive the car. We’re here to say, “Okay, make this left.” I want you to make an informed decision. That’s the role that teachers play.

It’s interesting, I’ve got all Wyatt Tee Walker’s books back here, and I’m thinking about Wyatt Tee Walker, who was, of course, one of the brains in Dr. King’s organization, the SCLC. I’m thinking about Barbara Ransby, who writes about Ella Baker, and not the first one but a great book about Ella Baker. What you see is these young people in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, like Marion Barry in southwest Tennessee, Mississippi, and so forth and so on. The students from Howard’s NAG, the Nonviolent Action Group, they met up at Shaw University, and they were going to start an organization, but Martin Luther King and Wyatt Tee Walker said to them, “Why don’t y’all become the youth arm of SCLC?” And Ella Baker said, “Slow your roll.”

Our job needs to be, to use Dave Chappelle’s metaphor, to be in the back seat. I’m not going to drive this car, but I’m going to help them if I know the road. What I’m not going to do is let you try to take the drive away. No, you should be in the back seat. Mind you, there’s nobody in this conversation who’s an elder, because even when we think about King or Wyatt Tee Walker or Ella Baker, we’re still talking about people who, if they were on this call, might be considered younger people.

So the youth movement, in conclusion, that we’re seeing in the streets now, I mean, I go down there, and I’ve been down on the 16th, and my job down here is to show support and show solidarity. If something goes down, to be here in case I need to jump in something, and also to say, “When we did this back in so and so, here’s what we learned: support, instruction, direction, and relinquish, so that we all move together.” And I think that’s what we’re seeing in the streets right now.

Rucker: I wanted to say thank you so much for tithing your time and your talents. You’re on fire. I just really feel the spirit of our ancestors here with us. You’re so well read.

Let’s go into this next question. So June 19, 1865, was approximately five to six generations ago. Since then, there have been many uprisings and other organized direct actions in the name of Black liberation. However, some non-Black people with societal position power, as of this conversation, are doing some things that some people read as a little funny. For example, some companies are giving their employees time off. Cuomo held a briefing about proposing to make today a New York State holiday. Even the internet is telling me that the Commonwealth of Virginia has declared today a state holiday. So what’s going on? Why is this holiday, or holy day as I like to call it, now getting so much exposure? What do you make of this? What questions should we be asking ourselves about this moment, and why are the concessions coming so fast? What’s this all about?

Carr: Well, Jessica, I’ll say this. And for those who don’t know, there’s probably a handful of people here who were also together last spring at WHUT, where Jeff hosted us for the Reconstruction teach-in. The energy from those conversations, I imagine it was hard for people to extract from the rooms and come back over here. So thank you. In our breakout room we were talking about this very thing. These concessions, one of the things we observed is that they’re coming much more rapidly than they did in the past. If we think about it again, this is going back to what Ursula said yesterday, if we can jailbreak time and space — and by that, meaning not think so linear — the first casualty will be American exceptionalism, which is fine with me. I mean, I didn’t ask to come over here. But since we’re here speaking English, if we can jailbreak it, we can then look at relationships between people who never met each other, between events that took place over the arc of decades and centuries. And if we can identify rhythms, we can then go through and see what’s similar and what’s not. To use Amiri Baraka’s phrase “the changing same,” and what does appear to be different.

So, Jessica, you mentioned something yesterday, and you said some more about a minute ago, this question of after Reconstruction comes this redemption moment. What did you mean by that? I know a lot of people study Reconstruction, but a lot of people don’t.

Rucker: Yeah, the rise of quote unquote “redemption” as I understand it is always the white vigilantism when white supremacy is leveraged through institutions and state sanctioned violence. It’s this notion that at any moment where there’s some kind of quote unquote “social opportunity” for Black people, there’s always organized white resistance at the individual and at the institutional and ideological levels. So one of the questions that professor Theoharis was probing at is the question that we want to get at; Are we going to get some living wages out of this? No, we’re going to dismantle the new Jim Crow. So, that’s what I mean by the rise of redemption. Will we see another wave as we’re getting through this particular political era, for example, with [president Trump]?

Carr: Yes. Well, that we can stipulate the answer is yes, we know we’re going to see because capitalism ain’t going nowhere without a death struggle. And it may be in its death rattle, but it’s going to go out with the embers burning as brightly as they can. So, we’re going to say yes. Now the speed with which we’ll see these kinds of nominal confessions — and there are people in this conversation who are much better read than I am with some of those early Marxists, like Antonio Gramsci — start talking about hegemony and see that when something is resisting hegemony, that hegemony will expand enough to incorporate that resistance.

So, whether you’re a reporter out there who will now get a promotion because they got to find the three non-white reporters and promote them immediately. We’ve seen that before. We saw that in the 60s, 70s, and 80s. I mean, Dorothy Gilliam has written a whole book about it, Trailblazer. So, if we’re going to see these corporations begin to make concessions, as we’ve seen so far, topical nominal confessions, then, quite frankly, for those of us on this call, we’re in a class where, unlike folks who had to go to work today in a different kind of way, even though we know a lot of those people, we’re in families with them, we can sit here talking to these screens for hours. That means that at some point somebody in our school buildings, somebody in our school district, somebody at our job is going to say, “We’d like you to come in and explain the whole entirety of history through the lens of Latinx, of Blacks. And could you do it in 20 minutes? Here’s $25.” I mean, someone’s going to try to recruit us into this. We’ve seen that before, too.

Booker T. Washington, for example, emerges in the 1890s, at the same time that this Redemption movement is unleashing racial terror in the country. He gave that cotton speech in 1895 in Atlanta, and three years later they had a coup d’etat in Wilmington, North Carolina. All this terror is going on at the same time. You cherry pick a few folks out to say, see, and then that’s when — Adolph Reed have written about this — the whole notion of the race leader, the individual. We have to resist that tendency now.

If we’re looking at this as a changing same and what’s similar, what’s different in this moment, I think what we can do is study Reconstruction, the first Reconstruction, study the second Reconstruction, or the second founding, and look at this third moment and say, “Okay, when they come with the money, we need to get it to these organizations. When they come to ask me to give a speech, I’m going to go give this speech because I’m recruiting other people who have been waiting to hear something, and we’re going to pull them off this plantation in the form of maroonage.” But we have to learn techniques of resistance.

Finally, the most important thing, as I said as we were talking about progress, as Jeanne Theoharis raised a minute ago, this structural advantage. They’re going to try to seize what Naomi Klein a couple of weeks ago on Democracy Now! was talking to Amy Goodman about, this Green New Deal. Here’s Cuomo with these guys who want to take all education offline and say, “Yeah, we’re going to bring all them in.” Now, they’ve been trying to do this for 30 years? We remember the MOOCs, we remember all this online learning. You think you’re about to make a quantum leap, but guess what? So do we. So when you show up with the Ivy League schools that say, “Take all our classes for free,” we’re showing up with the Zinn Education Project and saying, “Take all our classes for free.”

Then, of course, finally, I think — because that’s not going to help the person who loses their job in a structural realignment at a company — we’ve got to then identify ways to support folks, even as we continue to lobby, as we continue to practice electoral politics, we’ve got to continue to figure out ways to support those who are the most vulnerable. Because what I think is going to end up happening is this system is probably, if it’s not approaching its event horizon, it is very close, and it’s going to collapse in on itself. I mean, how many times have we been in meetings, all of us, where old heads mentioned something from the 1930s or 1940s, and they say, ‘capitalism is going to collapse’? We kind of say, “Yeah yeah.” I think we might be in the moment when we’re closer to that than ever before. Which means we’ve got to think differently now. And thinking differently means independent institutions, seizing the apparatus while it’s available to us, and then expecting as this resistance continues, they’re going to be other moments, when the state violence reappears, re-emerges, where extra police actions are taken, where the same kind of thing happens, but the system gets weakened every time. And these acts of desperation they’re doing now seems to me to just feed our determination not to relent.

Rucker: Well, thank you. To build on this notion of the system getting weakened everytime, there was a question about the third wave of Reconstruction, or the third founding. In harnessing these global interpretations, how can we leverage this moment, not just here in the U.S. but across the globe, especially in the context of global history and how it’s gaining momentum? I think this person was also asking about it in the context of higher education too, which you were starting to speak to.

Carr: I was watching Robin Kelley’s session, and he started his conversation by deconstructing three myths, and I thought that’s a good idea. So let me just say a couple of things very quickly at the beginning.

Number one: Every movement we’ve had in this country for equity, social justice, to strike against the general social order, has always had an international dimension, including Reconstruction. In fact, we were talking about sound. I ‘ve got a book around here somewhere on Reconstruction in a global context, because remember, France and England [were] sitting it out to see because the people in Charleston, South Carolina are telling them, “We’re going to run going into or out of Charleston. We don’t even need New York City.” Which is why of course, when South Carolina succeeds, the New Yorkers go to the governor and say, “Hey, maybe we should leave with them. Do you know how much stuff we get from the South?”

At any rate, there’s always been an international dimension. The Africans knew that before anybody. Julius S. Scott’s book, The Common Wind. You can go back to the 16th century. All of Gerald Horne’s work, all that stuff. And I love Gerald because Gerald is going to be charitable to The 1619 Project, Gerald is going to always be gracious to everybody. But let’s be very clear, The 1619 Project, with all the brilliant work it does, is an inward facing project. It’s kind of a domestic project with some international dimensions.

But the real trick, number one, is that all of this work has always been international, and it has been the threat of international relationships that has always facilitated the most severe crackdowns on domestic activity. The Insurrection Act of 1807 that this guy was talking about the past three years after the Haitian Revolution. They were terrified that these negros were going to start listening because these boats were going everywhere. The Insurrection Act of 1807, that’s one of the tributaries.

The same thing happens during Reconstruction. During and after Reconstruction, remember the Confederate States of America, their plan is a book by LSU Press, I forget the author, but it’s called Dreams of Confederate Empire in Latin America, or something like that. For the South to win the war, then you had to invade the North. They had to keep the North out and they wanted to run the CSA through Central America, and get Latin America too. Gerald Horne has some books, The Deepest South and The White Pacific, that deal with this. They tried to build an empire.

The resistance is also looking internationally. Just a quick Juneteenth example, just by way of symbolism, Antonio Damasio Smith, in the 1930s in Dallas, so you’re going to bring back Juneteenth because there were ebbs and flows after World War One. So, Antonio Damasio Smith, of course, is named for Antonio Machado, the bronze titan, one of the heroes of the Cuban Spanish War, in which the Americans jumped in. There’s an international dimension always to the way Black people in this country have fought. Coming forward into the 1950s and 1960s. We were talking about Paul Robeson, Shirley Graham Du Bois, W. E. B. Du Bois, Louise Thompson Patterson and her husband William, they have international connections. The NAACP, they’re going to be domestics, so they are forced away from them, or they choose to be away from them in this Cold War, anti-communism, kind of thing.

In this moment, the so-called third Reconstruction, or the third founding. I don’t think that’s going to work. That’s a radical difference in technology between the way we think about ourselves in the world as human before being a member of any particular national society. The solidarity movements we’ve seen all over the world in the wake of the murder of George Floyd and the previous murderers of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and so many others, those international solidarity movements bear strikingly similar tactics and techniques. So yes, of course, getting rid of statues.

How many years has it been from the epicenter of fallism in southern Africa? It started with labor. It started with Rhodes must fall. I used to take students to South Africa every year and we stayed on campus at the University of Cape Town. I would walk down to Rondebosch Road to get the newspaper in the morning, and I stopped by a Cecil Rhodes statue, and I spit on it every time. Now I can’t do it, since it’s gone. But Rhodes last fall. But then once they got Rhodes, they were like fees must fall. Then the workers and everybody else was with the students saying, “Rhodes must fall. School fees must fall. Let’s just call it fallism.” They’re saying Rhodes must fall in Oxford. In other words, the internationalism and then it comes to the shores of the United States and it didn’t quite penetrate. I think we might see a version of fallism because once the statues are gone, what else have you got? Happy Juneteenth. We’ve got that. You’re throwing these statues out here like some kind of artificial levy to stop this flood. Now we overflowed the statues. Where’s the living wage? I think we’re on that trajectory, if we can keep this momentum.

Rucker: That’s right. You just made me think of Beyonce. She said, “put some respect on my check,” and I think that’s definitely the next phase. I wanted to ask one more question. Then, if there are other questions in the chat, we’ll list those out, too. So, the internet has been abuzz with suggested readings and viewing lists and sites to make donations. You’ve given us an incredible amount of books to read, but do you have any suggestions about what we could be watching — organizations in addition to the Zinn Education Project that we could be supporting — so that as teachers and other adults who work with young people read and review, we can help pass on this message of liberation? Because it’s not just for me to keep it to myself; I want to keep passing it on.

I’ll give you an example. We had a PSA project in my class where students were asked whether or not we should continue to support institutions that use racist characters. One of those came from the film Ethnic Notions, of Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben’s rice. So, what should we be viewing, reading, or supporting so we can help pass this message to the young folks?

Carr: To me, the most important thing is what to look for rather than necessarily where to go. And I’m sure everybody on the call has their favorites, and I know that a list will be generated and circulated by the Zinn Education Project, I think that’s important, because what the Zinn Education Project does, in addition to everything else, it’s a clearinghouse, and it’s also a barometer of quality. Because if you see something that ZEP connects to, or that ZEP has, it’s going to be thoroughly vetted. I mean, you see how well organized these conversations are. So, there’s a standard there. Then it becomes, okay, let me transfer this standard to wherever I’m looking on the internet, and if I don’t see it at least approach this standard, then maybe I’ll put that on my secondary list. That allows us the freedom to roam without necessarily being direct.

One thing I’ll say, and this is somebody who stays broke from constantly buying books, and I’m looking at stuff and then the syllabi that are being generated. That’s the big thing now; what kind of syllabus, a Black Lives Matter syllabus? Yeah. Okay, that’s great. And I’m thinking to myself, how many people who are writing syllabi like this are teachers? Because every teacher on this conversation knows the challenge we have with having our students slow that moving image literacy down enough to adjust it to these words with no pictures. I see all the syllabi, and I’m like, this is great. Now I’m trying to figure out which one he was a teacher, because I don’t know if you ever tried to teach that syllabus, but if you have. I think syllabi is good for us, but they don’t necessarily speak to what we are trying, and need, to accomplish in the short term, which is to get our young people to do some of that.

Then, some of the other stuff, the moving image literacy, Ethnic Notions always suggests that. Something most people don’t hear, probably everybody has seen it — if not that film is excellent. Then, after that, I think, to me, it’s more about technique. Can you footnote a film? In other words, as you’re watching the film, assume that every moment you’re looking in that film is a set of narrative choices. That’s the way, for example, I think we should look at the PBS Reconstruction series. It’s good, but assume everything in there is a team of people’s narrative choices, and always assume that the choices they made omitted more than they included. So, what’s missing? As students, you always ask what’s missing? And if it troubled your spirit, that’s a signal that something’s missing. Because every kind of person there is today was back then, too.

That’s why, when people say, “These people were fighting for freedom,” and they said, one day, the rights that were assigned to George Washington belong, and I’m saying, now seem like they like George Washington in 1789, and why the hell would you come to 2020 and put those words in the mouth for people who did not like George Washington then? Oh, I see, you’re making a narrative choice. So, let’s blow up the narrative. That’s a little bit more difficult to do, I think, without guidance, which is why, again, I’ll end where I started, with the Zinn Education Project. I think that’s very important. [. . .] But the bottom line is this: you can have a book club, but how are you picking the books? I’m glad you read, and that’s the important first step. But the books we read should lead us to other books. There should be, at least initially, an initial set of books or readings that allow us to guide ourselves through. But, if you’re just getting around reading books, you’ve got to pick the book that somebody told you to read. So I guess that wasn’t an answer, but . . .

Rucker: I want to thank you, Dr. Carr. And thank you to our participants.

Carr: Thank you

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms, and hear an audiogram from the session below.

Resources

Resources shared by the presenters and in the chat box.

Here are some of the dates Dr. Carr listed.

|

This Day in HistoryJuly 5, 1852: Frederick Douglass gave the address, “The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro” |

Participant Reflections

Here are some of the responses by participants from the session evaluation.

What was learned

Responses to the question: What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today and what may you do with what you learned?

Reconsidering the particular moment we’re living as a a “founding” rather than as a third reconstruction. Powerful!

Dr. Carr was an amazing resource. There is so much I learned from being blessed to hear him speak. I copied and shared a plethora of resources I will share with my school.

I loved listening to the different days of celebration of Juneteenth, the idea of letting the young people “drive the car”

I loved the quote “citizenship shouldn’t shrink your humanity.” I love the idea that activism is intergenerational. I love learning the connection between reconstruction and what is happening today.

The role of Mexico and enslaved folks going South into Mexico- had never been taught that. Also, the re-emphasis of letting youth lead- really wanting to be in that role myself as someone who is 36.

I love the idea of not calling this period a third Reconstruction, but a Founding. I tried to quote Dr. Carr – “Are we founding a new society rather than a 3rd Reconstruction?” I want to pose this “thick” question to my students as we talk about Juneteenth and tie into the current events with the Black Lives Matter movement. I also want to discuss with my students about what does July 4 mean to different people (nationally and globally), why are holidays powerful (I think holidays serve as a talking point/intro, but they are NOT the end of a conversation).

The most important idea that I heard today is in relation to Dr. Gregg’s question, “Are we possibly on the verge of founding a society, rather than reconstructing one?” This question has my wheels turning and I definitely will be taking time to reflect upon this idea, with consideration with the socio-political uprisings of present day.

I had not learned about the Contraband Acts prior to today, nor Watch Night, nor the concept of freed vs. free. These new pieces of information will enrich my teaching of the Emancipation Proclamation, Juneteenth, & Reconstruction.

This quote from Dr. Carr was really powerful for me: “Are we possibly on the verge of founding a society rather than reconstructing one?” Considering all the Reconstruction periods our nation has had, and the idea of moving forward to found something new instead of trying to rebuild the old, is really encouraging and inspires me to keep doing the work with my students!

There were so many! I think the biggest one was paying attention to who is controlling the narrative on what I am viewing/reading. Everything Dr. Carr was saying was amazing and I couldn’t take notes fast enough!

I could barely write fast enough, but I was blown away about the discussion about the relationship between poor Whites and the enslaved. This is a standard I teach about the relationships between groups and I had never considered this relationship.

The new questions of “who are they to each other?” and “who are they to others?”

I learned how important it is to focus on who people were to one another when studying history, not just who they were in relation to other groups. Ask “what’s missing?”

I appreciated Dr. Carr sharing his understanding around the process of “redemption” after an uprising. I have felt so much resistance internally to the small, cosmetic concessions from corporations, politicians, and even other organizers. Good to know we’ve been through this before and that there is a blueprint from history on how to keep pushing for full and total liberation. And thank you for the important reminder for guides to take a back seat!

Who are/were African people to each other? This is and will continue to be the driving question in my courses.

So many!! The idea that we are in a third reconstruction or a “founding” moment really stuck with me. Dr. Carr’s quote “We should not be ranking people’s humanity by their legal relationship to the state” and the idea that we have done this in so many ways over time in this country. The idea that Juneteenth is celebrated on different days in different places made the true meaning of Juneteenth hit me on a deeper level. I plan to read Teaching for Black Lives and watch Ethnic Notions, which I learned about in this session.

Freed vs free, and founding vs reconstruction. I appreciated learning about Mexico welcoming and granting freedom to escaped slaves — that was new to me.

Amazing session! The very idea of spreading the word from Virginia to Texas blew my mind — so visual — the wave. So many brilliant ways of putting things, Dr. Carr.

Rethink and reimagine the questions we ask, how we frame lessons. I am rethinking how I frame the school year, how I will insert movements for freedom as people continue to become freed, bring in more analysis of citizenship, international connections. Also, thinking about how to being this reframing and rethinking to my school.

This session made me totally re-evaluate how I think and will talk about Reconstruction in the future. Love the idea of creating a new foundation.

The format

Everything was great! I’ve enjoyed the format each time. And I appreciated, very much, the explanation as to why the breakouts are included and how they “live out” the pedagogical and philosophical underpinnings of Zinn Education Project.

The format was incredible. Jessica was a wonderful facilitator and Dr. Carr was absolutely brilliant. The break out rooms, as always, allowed for a chance to process and discuss the concepts.

I enjoyed it all – very well done! I wish we had more time in our breakout rooms, but at the same time I wanted more time with Jessica and Dr. Carr! I want to be in Jessica’s classroom!

Everything was just great. Jessica was an outstanding host. She asked such brilliant, targeted questions. I could also listen to Dr. Carr for hours. Many thanks to you!

The relationship between Jessica Rucker and Dr. Carr made the conversation feel so intimate and rich. This was a great learning opportunity.

The format is about the best I have ever experienced. The breakout groups are just long enough to give a feeling of connectedness.

I liked the structure. I loved how Rucker and brought in her perspective as a teacher, what was successful in her classes (I will be buying It’s Bigger Than Hip-hop because my students enjoy learning about allyship), and how she has collaborated with Carr at Howard. I loved being able to talk to others. I would love to be in a breakout with other middle school teachers, because as Carr mentioned, curriculum that is produced isn’t always easy for me to implement because I have to differentiate it, which is difficult with the rush of a school day and a school year. I know other break-out groups would make the time go longer, but I would love to add in a break-out to talk to grade-alike groups.

Additional comments

These sessions continue to be the highlight of my week!

Thank you so much! I appreciate the opportunity to have Dr. Carr as a teacher for a few minutes. Jessica, your students are very lucky to have you as a teacher

Jessica is amazing. I remember working with her in a breakout room. I wish I could be in her classroom in DC. I love hearing from Black people in DC!

Dr. Carr was SO AMAZING and PASSIONATE and FIRE, perfect for the day of Juneteenth!

We are better for your collective work! THANK YOU!

Dr Carr is such a great person with so much knowledge and I cant wait to follow his work more and see him speak more and dive into the rabbit hole of all his work online and offline. What a genius!

I keep thinking these sessions couldn’t get any better, but they do every time.

This whole series is a lifeline. I am so grateful.

Thank you – so much positive energy in today’s lesson, I left feeling so energized and inspired!

Thank you for modeling how we can teach with active learning models in a Zoom classroom (polling, engaging chat convos, BREAKOUT ROOMS! and the breakout room guidelines beforehand, appointing facilitators, etc). This is beautiful and although I’ve tried these things in my Zoom classrooms this past semester, I am more dedicated to implementing these things in my Zoom classes this fall. P.S. DR CARR AND JESSICA ARE AWESOME. P.P.S. WHERE CAN WE GET THE IDA B WELLS SHIRT THAT DR. CARR WAS WEARING

Jessica Rucker again did a fabulous job facilitating and her candor and clarity brought so much to the experience of meeting Greg Carr. Seeing she would be facilitating was a draw to signing up (though who am I kidding, I am signing up for all of these great online events now that school is out, but Jessica is still a draw and made me more excited for today!)

Thank you so much for hosting this series. It’s a privilege to attend.

Presenters

Greg Carr is associate professor of Africana Studies, chair of the Department of Afro-American Studies at Howard University, and Adjunct Faculty at the Howard School of Law. Carr is co-founder of the Philadelphia Freedom Schools Movement. Carr is an advisor for the Zinn Education Project Teach Reconstruction campaign. See Carr’s two-minute history lessons on key figures and events in U.S. history.

Jessica A. Rucker is an electives teacher and department chair at Euphemia Lofton Haynes Public Charter High School in Washington, D.C. She is a member of the D.C. Area Educators for Social Justice and was a participant in the 2018 NEH Summer Teacher Institute on the grassroots history of the Civil Rights Movement. She is a native Washingtonian and community accountable scholar with more than a decade and a half of youth development and community education expertise.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn