On May 29, the weekly People’s Historians Online session on the history of feminist organizing was held as the nationwide rebellion in protest of police brutality was on everyone’s hearts and minds. Barbara Ransby talked about the activism of Mamie Till Mobley when her teenage son Emmett Till was lynched and attendees immediately thought of the parents of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and George Floyd, who had been murdered by police or vigilantes in recent weeks. In their evaluations, participants noted the importance of coming together at this time:

Honestly, this was an hour of love and catharsis for me. I definitely thought differently about how to encourage my young people and how to teach them about their own ability to organize and their own power. But I really felt renewed and empowered by this community, particularly today.

Thank you for making the explicit connections to what is happening today. This history is important, but what makes it powerful is learning to apply what previous generations have fought and died for to improve conditions today for the future generations.

First, THANK YOU, this moment, this day, as the fires of rebellion swirl around us all, was a blessing. Wherever one is along their respective continuum of educational activism, humility is key to any effort to move forward. I am grateful for the work to make this richly textured and nuanced opportunity for learning/reflection available.

Ransby reminded us that the role of being an educator is not a neutral one. “I am an activist and a teacher,” she said. “I share my political beliefs with my students. Not to indoctrinate them, but how cynical would it be to say, ‘I’ve spent all this time studying and I have no position on what is right?’ That would be irresponsible to our students.”

We offer below highlights of the session, a full video recording, recommended resources, and participant feedback.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: I want to welcome everybody on behalf of the Zinn Education Project for our session today on Black Feminist Organizing: 1950s to the 21st Century. I feel like these Friday classes are always important; they’ve really sustained me ever since schools have been closed from COVID. But today’s session, I think, feels particularly urgent in the wake of the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery.

I think more than ever we need to teach for Black lives. Deborah was saying that she’s getting a lot of requests for how to begin to address this moment with classes, so I just wanted to take a second to let folks know about this resource, Teaching for Black Lives. It’s the book that I helped to co-edit with Dyan Watson and Wayne Au. It’s full of lessons for how to address moments like we are in right now, how to talk with youth about police violence and police murders of Black people, the history of it, [and] how to organize today. So, I want to highly recommend people check out that book and other resources at the Zinn Education Project.

So I’m Jesse, I’m a high school teacher and editor with Rethinking Schools, which coordinates the Zinn Education Project along with Teaching for Change. The Zinn Education Project is hosting this session today and offers free downloadable people’s history lessons that many of you have already used for middle and high school classrooms from the Zinn Education Project website. Before I begin my conversation with the great Barbara Ransby, we want to find out who is in the room and go through our plans for our time together. We are going to do a quick poll now to find out how many teachers, librarians, teacher educators, historians, parents, students, educators of all kinds are with us in the room today. Many of you are in multiple roles, so just choose your primary role that you’re in as educators. Cierra Kaler-Jones will post a poll now for you to respond to.

As those numbers compile, I’ll let you know that throughout the session, we want you to use the chat box to post questions, comments, resources, ideas. Our guest speakers will read your questions and try to respond after the breakout groups. And we’ll do a short evaluation at the end. So, make sure you look in the chat box for the evaluation form link and fill that out before you leave this session today. It looks like the results are in: 51% of you today are educators, 14% are students, 1% are primary family members or caregivers, 3% are librarians, teacher educators 16%, 9% for historians and 6% other. So thanks, everybody, for being here today, being in community with us at this critical time. We’re ready to start our conversation, and after about 20 minutes we’ll pause so you can meet each other and talk in small groups and share insights.

So, it is my honor and pleasure now to introduce you to Barbara Ransby. She is the author of three invaluable books: Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision, everybody needs to pick this up for sure; Eslanda: The Large and Unconventional Life of Mrs. Paul Robeson; and Making All Black Lives Matter: Reimagining Freedom in the 21st Century. So welcome, Barbara, thanks so much for being with us today.

Barbara Ransby: Thank you so much for having me. It’s a real honor to participate. I have a lot of respect for the Zinn Education Project, of course, and I knew Howard Zinn and always love to see projects continuing in his memory and legacy.

Hagopian: That’s beautiful. Thank you so much. I just know that this discussion is so critical for teachers and teacher educators around the country and I’m really excited to jump in with you. I thought before we get down to looking at some of these incredible Black women organizers and get into the specifics of some of their lives, I’d start with a general question to frame the discussion, because I think so much of the standard corporate curriculum that we’re given as teachers in the classroom from corporate textbooks really excludes the contributions of Black women throughout history.

I’m reading a book called A Black Women’s History of the United States by Daina Ramey Berry and Kali Nicole Gross. They write, quote, “All told, Black women’s history in the United States is broad, beautiful, exciting, haunting, and crucial to understanding the nation. It is a testament to the intellectual richness and vitality of Black women. The history also holds the country accountable for its still unmet promise to make democracy serve all equally.” So, I thought maybe you could just start by talking to us about what happens when Black women are left out of the narrative in our classrooms, and then what becomes possible for students and teachers and the community when we do examine the history of Black women and the movements for liberation?

Ransby: Well, thank you for that very expansive question. I also feel like I should preface my answer by talking about Black women’s history with this current moment, which you opened us up with. One of the things that I was doing late last night and early this morning, and we’ll be doing again tonight, is being in conversation with mostly young women activists who are really on the frontlines of the struggles that are unfolding in Louisville, in Minneapolis, and in Georgia right now. I think of people like Kandace Montgomery and Miski Noor, and others in Minneapolis who are taking up the question of police violence, very much in the tradition of Ella Baker, Ida B. Wells, and Diane Nash, of previous generations.

So, there’s the history, which is very rich, and then there’s the contemporary reality of Black women activists being on the frontlines of the fight for justice. So what is left out and what do we benefit when we include Black women’s stories?

I was asked to do a little review of a recent series on Hulu called Mrs. America, and a number of people have reviewed it, it’s about the 1970s fight for the ERA. A number of reviewers felt like it was more inclusive than other documentaries about second wave feminism and I had the opposite reaction. I thought of all the Black women who were marginalized, excluded, left out, barely footnoted in that series, and who were involved in absolutely robust organizations, campaigns, etc., in that period. What would their stories have told us about people like Flo Kennedy, who was an amazing lawyer and activist, people like Margaret Sloan, who was one of the early editors at Ms. Magazine. It’s not just a question of coloring in the picture, adding some sort of cosmetic change to a narrative, but we really transform how we understand history when we include Black people, and especially Black women.

In that case, in particular, those women were not involved in the fight for the ERA as a simple narrative, narrow struggle, but rather saw it as a part of a larger struggle for social transformation. In that period, many of them were involved in the Black Freedom Movement, they were involved in the anti-Vietnam War movement, etc. So, through their biographies and through their political careers of activism, you connect gender issues and feminist issues to a whole wide range of other issues.

Also, when I think of pioneering historians and writers like Beverly Guy-Sheftall, Paula Giddings, and Darlene Clark Hine, who really inserted and intervened into a predominantly white and male narrative of U.S. history to recover and insist upon the inclusion of Black women’s stories and Black women’s voices, but also pushing beyond inclusion to transformation to say, “Now that these voices are here, what do we learn? We have a different narrative about leadership, we have a different narrative about cultural production, we have a different narrative about political engagement,” et cetera. And many wonderful historians today of course, like Jeanne Theoharis, is a part of this project; Darlene Clark Hine, Sherie Randolph, Ula Taylor, Sarah Haley, many others, Ashley Farmer, who are writing amazing histories that change the way we think about a wide range of issues, from Black nationalism to marriage. So, Black women’s stories are very important. But again, not simply for cosmetic inclusion or what we might term diversity, but really for the transformative power of those narratives to reorient our thinking about major themes and periods in U.S. and in world history.

Hagopian: I love that we’re not just adding color to our historical curriculum, but when we look at the legacy of Black women organizing, it really transforms the whole narrative of what the organizing looks like, what the methods are. I think that’s such a powerful lesson for us.

I want to ask all the participants today, a poll question with regard to Black feminist organizing and the history of Black women and movements for liberation. I’m interested if you’ve learned about these things already in school, or what’s been left out for you. So, check out the poll that’s up on the screen right now and fill that out, because we’re curious what you’re learning and where the gaps are. I know two of the gaps for me are in my next question for you, Barbara.

I was not taught about these important Black women in my experience in K–12 education, but have since helped to transform my understanding of the movements we need to build. So, there are many Black women leaders that we could talk about today, but I thought we could look at a couple of them that are specifically interesting to me because they are educators and teachers. I wonder if you can share more about Septima Clark and Mamie Till and their contributions to the Black Freedom Struggle?

Ransby: Sure, and those are great selections too. I mean, there’s so many places we could go and it’s always a temptation to do a laundry list. But a little bit deeper dive on a few really critical historical characters, I think, is rewarding.

So, Mamie Till-Mobley was the mother, famously, of Emmett Till. But, as you point out, she was also a teacher. She was known as Mamie Till, she later married a number of times in her life, but her final husband was named Mobley. She took his name, so she’s known as Mamie Till-Mobley. She was a domestic violence survivor herself from Mississippi, the bastion of Jim Crow segregation and racism. In 1955, her her teenage son, Emmett Till, was visiting one of their relatives in Money, Mississippi — ironically named — and was the target of vigilante violence and the target of a vicious murder and lynching. Lynching in the sense of a violent, racially motivated murder for allegedly speaking inappropriately to or whistling at a white woman in a store, or clerk in a store.

This is a theme that emerges repeatedly in African American history. In the history of racial violence is the connection between race, gender, and sexuality. So, this young boy had violated one of the taboos of southern racism and white supremacy at that time. It’s not even clear that he said anything inappropriate, but he reputedly said something inappropriate to this woman, was dragged out of his uncle’s house in the middle of the night, tortured, murdered, and thrown into the river. Now, that is a Mother’s Day nightmare, certainly a Black mother’s nightmare in that period, for this kind of fate to befall her child.

Mamie Till demonstrated enormous courage, fortitude, and foresight in allowing the case of her son, allowing her own personal suffering and tragedy to be used as an educational moment, really as a political mobilizing moment. She insisted upon the casket of Emmett Till being an open casket during the funeral. It was featured on the cover of Jet magazine, a popular African American magazine. That image became a powerful symbol of white racist violence in the south. So, she herself then — in addition to being a teacher, which was the career she chose later — went on tour with the NAACP, talking about Emmitt Till’s murder, talking about the issue and scourge of racial violence. And she continued with both her teaching and her activism for much of her life.

She lived here in Chicago and died in 2003. But, even in her later years, she would appear at a number of events and really saw herself as a part of a Black Freedom Movement, as part of a human rights and civil rights movement for the remainder of her life. I’m reminded of the strength of Black mothers like Mamie Till-Mobley: In addition to being a teacher, she was also a mother. When I think of someone like Gwen Carr, who spoke just last night in Minneapolis, who was the mother of Eric Garner, who was murdered — similar to George Floyd — in Staten Island, New York a number of years ago — also strangled to death by the police. So, Mamie Till-Mobley is very much in the tradition of Black mothers turned political activists.

Septima Clark, a teacher in South Carolina, had Haitian roots, which I always find an interesting piece of her history. Born in the late 19th century, in 1898, she was first a teacher without formal training, [then] she took the teacher’s exam in South Carolina before she actually went to college. I think that’s always an important lesson, because those of us who’ve gotten most of our education in formal academic institutions forget about the enormously important and rich tradition of self-taught teachers, of griots in our community, of people who have a vast amount of knowledge to share and really hone the craft of teaching, sometimes learned outside of classrooms. So that was where she began.

She later went on to get her BA and her Master’s, but she is best known for being the person that began the Citizenship Schools. These were initially literacy, schools that helped Black people learn how to read so they could pass literacy tests and vote. But also, as she began to expand that curriculum and worked for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, worked closely with Dr. King, serving on the executive board of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference at one point, and also fighting around issues of equal pay for teachers, fighting the battle to have Black teachers allowed to become principals in schools in South Carolina, with victory that was won in the 1950s. She actually lost her job in 1956 because of her membership in the NAACP. It was illegal for teachers in the state to be members of that organization, because it refused to comply with demands that it give up its membership list. So she was fired from her teaching job and then went on to be a full time organizer with the Citizenship Schools in the movement. So, that’s just a little glimpse into the lives of two very important women.

Cierra Kaler-Jones: I think that Jesse’s internet might have gone out, so I’ll continue the conversation as he comes back. I would love to talk to you about Ella Baker. One of the towering figures of the Black Freedom Struggle from before, during, and after the Civil Rights Movement is of course Ella Baker. Corporate curriculum is all too silent about her contributions. In your biography of her, you describe Ella Baker in several ways — as a grassroots organizer, an organic intellectual movement leader, although of course, she was very critical of a certain model of leadership that focused on one charismatic individual. But, there’s one way you describe her that I think is especially relevant for all of us here today. And so you wrote,

Ella Baker was a movement teacher who exemplified a radical pedagogy similar to that of Latin American educator and political organizer, Paulo Freire. She sought to empower those she taught and regarded learning as reciprocal. Baker’s message was that oppressed people, whatever their level of formal education, had the ability to understand and interest the world around them, to see the world for what it was and move to transform it.

So, we would love for you to talk about the pivotal role Ella Baker played in the development of the Black Freedom Movement, especially for youth and women.

Ransby: Well, thank you. I never tire of talking about Ella Baker; she holds a special place in my heart. I spent many years of my life researching the biography and really just trying to do her justice in telling her story and her lifelong career as a teacher. She was never paid to be a teacher, per se. Well, she actually was paid to be a teacher briefly. I’ll talk about that in a minute.

But she actually had a skepticism about going into the teaching profession, in part because that’s what her mother wanted her to do. Initially, she thought that was what was expected of middle class Black women of her generation. She was born in 1903, so she was a little bit of a rebel and she was like, “I don’t want to be a teacher. I’m going to do something else.” But ultimately she came to serve as an educator in very unconventional ways.

There’s sort of three phases to her career as a movement teacher. One begins in the 1930s, when she works in a special program that was a part of the New Deal called the Workers Education Project. She worked in that project with people like Conrad Lynn, who went on to be a civil rights lawyer; Pauli Murray, who some people have heard about, also a movement lawyer; and a number of other folks. They taught what they called negro history at the time, African American history. They taught a little bit of African history, but most importantly they experimented with pedagogy. It was an adult school, so it was a school for workers, some of them immigrant workers, many of them African American workers. The classroom that she taught most often in was in Harlem. She really experimented with knowledge production and with teaching methods, and really tried to engage in classroom practices that were egalitarian and democratic with, again, that sort of Freirean model that ‘every teacher is a pupil and every pupil is a teacher.’ She organized a number of courses in her role as a Workers Education Project teacher in the 1930s in New York.

The second part of her teaching career, if you will (again, it was never the job description, but that is part of what she did) came in the 1940s, when she worked in the NAACP. She worked in the NAACP first as a field organizer, as a field secretary, and then as the director of branches. When she worked as the director of branches in a national leadership role, she organized leadership training sessions throughout the South. If people have either read my book or know a little bit about the NAACP history, she titled them “Give people light and they will find a way.” Give people light and they will find the way. Which reflects both her approach to teaching and her approach to leadership — very grassroots, very decentralized, very much looking at the reservoir of knowledge and wisdom that students, that grassroots organizers, that members in the case of the NAACP, brought to the table in a learning or training environment. In those leadership training sessions, they talked about theories of change, they talked about the history of social movements and of the Black community, and they talked about empowerment — how people could empower themselves as leaders. So, that was her second phase.

Then her third phase, which is perhaps what she’s best known for, is her role as a movement elder in SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which of course begins out of the desegregation sit-ins in 1960. Many people I interviewed for the book who had been involved in SNCC saw Ella Baker as a movement teacher, many of them said her style was pretty distinctive. She wasn’t the kind of teacher that gave you a long lecture or insisted that she had all the answers. But she actively listened, she encouraged people to find their own voice, to find their own explanation for things. Then she would intervene very strategically and share what she knew, and also what she had heard from those young people.

The final thing I’ll say about Ella Baker, and you’ve mentioned working with youth, sometimes we talked about Ella Baker’s intergenerational organizing in a way that I think kind of fetishized youth. Ella Baker a lot with the young people in SNCC. She was old enough to be their mother, their grandmother in some cases, but she aligned with them as an act of political solidarity. Martin Luther King was closer in age to the young people in SNCC, but further away in terms of where their politics were evolving.

So Ella Baker really saw something in them. There were other young people she chose not to work with, because she did not have any kind of political solidarity [or] alignment. She didn’t work with them just because they were young people. In other words, she understood that because they had a certain set of political values that they were aligning around, that there was enormous potential there. And what added to it was their youth; but youth was not the defining variable. So, I just always like to add that because there’s, sadly, conservative youth players, right wing youth, they’re apathetic youth. Being young is not a guarantor of being a transformative agent for change. But, we hope that our students will become that. I guess that’s what I’ll say about Ella Baker and her style of teaching, her approach to teaching inside the movement.

Hagopian: I really liked your treatment about Ella Baker, her approach to youth, the book, and everything you just laid out about how she saw that there was great potential among the youth to go farther than some of the older activists had gone. But she also knew that there were different political outlooks — no matter how old or young you were — and I think that lesson is a real take away. So thank you for that.

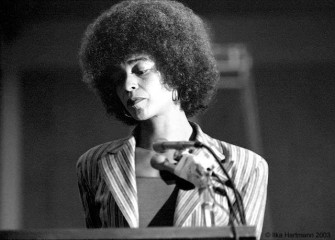

Just moving forward on the timeline, I would love to hear you talk about the leadership of Black women during the Black Power era and the way they led revolutionary struggles against institutional racism and capitalism, but also struggled against sexism in the movement. There’s so many people we could talk about: Angela Davis, Ericka Huggins, Assata Shakur, but who are some of the ones that you’re drawn to?

Ransby: Well, I mentioned a few of them at the outset when I talked about the Mrs. America series, but I’ll say a few more. SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which Ella Baker was really an inspiration for — she convened the first gathering of SNCC organizers in 1960 and the group evolved from there — but out of SNCC emerged a number of really important women leaders and organizations.

First was an organization that Fran Beal, member of SNCC, formed that evolved into something called the Third World Women’s Alliance, a very important organization that was first a Black women’s group. Then they met with Puerto Rican women in New York and talked to other women, women of color from other parts of the world, or who traced their ancestry from other parts of the world. And they expanded it to describe themselves as third world women, mainly meeting women from the Global South. And, of course, this is the time of the Vietnam War. This is the time of some of the final battles of the African liberation struggle on the African continent. And so it was really an organization that saw itself in a global context, Fran Beal being very important to that organization.

Another organization is the Combahee River Collective, explicitly a Black feminist organization. Now, we don’t think of these as necessarily Black Power or Black Liberation organizations, but they are. They are a part of a larger ecosystem of Black radical politics in that period that are looking at not only issues of gender and race, but also imperialism and capitalism. So, the Combahee River Collective is explicitly a group of radical Black lesbians who are opposed to white supremacy. They’re post-imperialism, they’re opposed to war, and they are opposed to capitalism. They had a very sharp critique of capitalism as one of the pillars of oppression for Black women.

In this period, Barbara Smith was one of the founders of the Combahee River Collective, and later went on to found something called Kitchen Table Press, which published a lot of books by women of color in the 1980s. Audre Lorde, another poet and Black lesbian activist was very much a part of that.

Angela Davis probably warrants special mention. Angela connected to a number of different parts of the Black Liberation Struggle in the 1970s and continues to be an activist to this day, and a great source of inspiration to many of us, as a Black feminist abolitionist. But many people know the story of Angela Davis. When she was first fired from University of California for her leftwing political views, then later implicated and arrested for what was alleged to be her role in an attempt to free George Jackson, who was a prisoner in Soledad prison. It was in a courtroom, as it turned out, someone had taken her gun, George Jackson’s younger brother.

She was on the FBIs Most Wanted list and became a symbol of Black resistance in the early 1970s. Her image — large Afro, fist raised — became very iconic in the 1970s. I recently participated in a gathering at the Schlesinger Institute at Harvard, where her papers now reside, and it was a two-day program that spanned her life. I was honored to be on the panel that talked about her feminist politics and contributions. But just in hearing the breadth of her influence from the organizations of the 1970s to the formation of organizations like Critical Resistance, it’s very impressive what Angela Davis has meant to the Black Freedom Movement in the United States.

Hagopian: Absolutely. And thank you for raising the Combahee River Collective. I’ve learned so much from Barbara Smith, and the way that they created an intersectional politics before the word was being used.

Ransby: It’s so important, isn’t it? I mean, in some ways, we can trace intersectionality Sojourner Truth in 1851, when she said, “Ain’t I a woman,” because she was raising the contradiction of different models of womanhood, of different forms of gender oppression that intersect with race and with class. So, before there was a fancy name, which we’re grateful to Kimberlé Crenshaw for all her work, and for naming it. But the practice, the understanding, existed before we had that term.

Hagopian: Excellent. Well, we’re going to come to our last question here, and it’s about what’s going on today with the Black Lives Matter movement. We’ve seen a resurgence in the long Black Freedom Struggle for our times, and in your book Making All Black Lives Matter, it’s really been important to me in situating this current round of struggle in the context of a generations old fight for freedom, and I really got a key insight in your book. Everybody should get Making All Black Lives Matter: Reimagining Freedom in the 21st Century.

Ransby: Thank you for that ad, no doubt.

Hagopian: And you wrote, “Black feminist politics and sensibilities have been the intellectual lifeblood of this movement and its practices. This is the first time in the history of U.S. social movements that Black feminist politics have defined the frame for multi-issue Black-led mass struggle that did not primarily or exclusively focus on women.” This really struck me and made me really hopeful for the future of this struggle. I’m hoping you can talk more about what you meant here and where you see our movement going.

Ransby: Thank you for that. When the murder of Trayvon Martin happened, and George Zimmerman — by all indications the man who murdered him — was let off, it triggered activism throughout a landscape or ecosystem of young Black organizers. Black Youth Project 100 was founded around that time, the Dream Defenders in Florida were founded around that time, and both of these groups become very instrumental in setting the tone for the 2014 uprising and the organizations that emerged after the murder of Mike Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. At the center of both of those organizations, when I interviewed people and as I engaged in my own political practice with those young people, were feminist ideas of intersectionality, of bringing the marginalized to the center, of having a critique of systemic change, of not allowing gender to be marginalized, of naming the inclusion of LGBTQIA activists and members of our community, all of that was very much at the center of their understanding of the work that they were doing.

In previous generations, certainly in my generation of activists, there was a fight to recognize the importance of gender and of women’s leadership in the Black Freedom Movement. Angela Davis fought that fight. Fran Beal fought that fight, and many others did, and have spoken and written about it very eloquently. But this was a struggle that feminist organizers consciously — unapologetically feminist and many of them queer — were the catalysts for the organizations that emerged out of that struggle. Now, I’m not saying that everyone on the streets in Ferguson was a Black feminist; that clearly was not the case. But the organizations — the BlackOUT Collective, the organization Blackbird, which became a group that organized media and tactics and infrastructure for the Black Lives Matter movement, which has now morphed into the Movement for Black Lives, and the Dream Defenders, and the Black Lives Matter global network.

Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Ayọ Tometi, those three women identify clearly as feminists. They are very clear about that. They were influenced by people like Angela Davis, by organizations like Critical Resistance, by INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence. All of these were the precursors that set the tone and the landscape for that movement as it emerged.

So, even on one level, we see Black men as having been the primary victims of a lot of the police violence, even though, of course, Kimberlé Crenshaw, BYP 100, and others have foregrounded the often hidden cases of Black women. In this most recent phase, Breonna Taylor represents that; before, [it was] Sandra Bland, and many others, and many trans women in particular. But we often think of the more prominent cases, which have been cases of Black men. So the fact that Black feminists are at the core of taking that experience and turning it into a larger movement for change, which includes a feminist analysis, is pretty powerful. I tried to lay that out in the book. It has not been a struggle in that movement that has not had challenges. It is not uniform. But, I would say that quote reflects that the core ideas that have propelled the work and the organizations that have come out of the 2013 and 2014 Black Lives Matter movement have been Black feminist thinkers and doers at the core.

Hagopian: That’s really exhilarating to me, to think that we are making progress historically, that we now have Black feminist politics at the core of some of our most important social movements. And just what you said about those politics guiding the movement, I mean, I see it in the work I do with Black Lives Matter at School, we have a week of action nationally, the first week of February, and we broke down the 13 principles of the Black Lives Matter global network, with teaching points for each day of the week.

[breakout rooms]

We have a couple of questions already, so we’ll start with those, but then we’d like to hear more questions. I’d like to ask Barbara about how we teach right now, in this time that we’re in, where we’ve had some recent horrific murders of Black people by police. There’s a new rebellion growing in cities across the country. What do you think is important to highlight and how to teach to this moment?

Ransby: It is such a challenge to both reassure young people that they can go out into the world and not go out into the world with fear every step, but also to respect them enough to share with them the reality and the challenge that they need to fight for justice. And we all need to fight for justice because we’re far from there. So I think striking that balance between not absolutely paralyzing young people with fear and also sharing with them the complex reality of continued racial injustice. In this current moment, particularly because the protests have been intense and militant, and they spin buildings on fire and police in riot gear, we think of Ferguson. People saw those scenes, young people saw those scenes.

So what to make of them? I think the language we use is very important. Humanizing the cast of characters is very important. Giving people a context, a frame for understanding someone in the language we use. I mean, you use the term rebellion, I use rebellion, or uprising. That’s an invitation to talk about what are the causes of these protests. It’s not a riot; it’s not just people flipping out and randomly doing violent things, right? It comes out of a passion and an anger and a rage that was sparked by something very specific, and a pattern of very specific activities on the part of police attacking the Black community. So, I think that’s important. I think giving a short term, an immediate, and a long term view. Like when we look at other rebellions and uprisings that have happened, they don’t go on forever. What communities and organizers do after a rebellion and before is as important as what happens in the context of rebellion.

I remember I was growing up in Detroit in the 1960s, and 1967 was one of the most famous uprisings of the 1960s. In Detroit, it was in my neighborhood, and I remember my 10 year old self thinking, “Wow, what is going on here?” I’m seeing things I hadn’t seen before. I was initially afraid. But actually, there was a sense of community, camaraderie, and community care among my neighbors when the police and the National Guard came into our communities. So I think looking at the trajectory of how people have experienced rebellions, and then what comes out of them. Often after a rebellion is a sobering time, where many people who weren’t prepared to look at those issues before are prepared to look at them. So, giving students the understanding that even out of what seems to be a scary and chaotic moment of protest — and often they are because we don’t know which way things are going to go. It’s not scripted. It’s not, “Here’s our list of demands, here’s our tactics, and here’s our spokesperson.” Things can go in lots of different directions.

But, often out of that chaos and confusion emerges certain changes that people can hold onto. But, then of course, you have to fight for it. We were talking a little bit in the breakout room about some of the people who have been left out of our conversation so far. When I think of teaching this moment and talking about police violence, I’m talking about the refusal of people to allow that to happen quietly, without making a lot of noise, without even putting themselves at risk, in order to draw attention to that injustice.

I think of someone like Gloria Richardson, who is in her 90s now. But in the 1960s, and in 1963 in particular, she was an organizer in the Civil Rights Movement, closely aligned with SNCC, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and led a very intensive, very militant struggle in Cambridge, Maryland, where she allied the Black community — many of whom were workers, and had labor grievances — with people talking about desegregating schools. The protests turned militant, turned intense, and the National Guard was brought in. And Gloria Richardson was the beacon of determination and calm in the middle of that very intense struggle, which was, I’m sure, very scary for a lot of people. So I think about those moments and chapters as ones that we flashback to and we can put in context and see in the whole scheme of things, the whole spectrum of tactics that often uprisings and rebellions are the catalyst, the spark, that takes struggles to another level, that gets the attention of people in power when other tactics fail. Finding ways to illustrate that to students [is important]. Some of the interviews that have been done with Gloria Richardson, some of the things had been written about her, and also some of the other folks that we know from the Black Freedom Movement of the past who were in the middle of these situations and come out the other end, helping to shape, sustain, and bring concessions out of those struggles. That’s probably my best advice as a pedagogical approach to this.

Hagopian: Thank you so much for that. I think that is going to be really important to a lot of us here, because oftentimes when we bring these issues into the classroom people accuse teachers of, quote, “politicizing the classroom” by talking about Black Lives Matter. But the reality is that the students are [already] having these conversations about what’s going on in the streets of Minneapolis and around the country. So the question for us educators is: Are we going to actually educate the kids about the things that they most desperately want to know about, or are we going to make education irrelevant to their lives?

Ransby: If I could just follow up, I think there’s two things that that brings to mind. I’m an activist and a teacher, and I share with my students what my political views are. I don’t do that to indoctrinate them or to say they have to agree with me. But, what does it mean for those of us who study, research, write about, and teach about freedom and justice, and Black history, to say we’re agnostic, we have no opinion about it, we don’t care about it. That, to me, is a much more cynical conclusion than to say, of all the things, all the books I’ve read, all the things I’ve learned, here’s what I believe is right and fair and just. To offer that up to our students, I think, is also a way of modeling what it means to be a conscientious person, a politically engaged person, etc. It doesn’t say they have to always agree with us. But to try to stay aloof from the political and moral questions embedded in the work that we do is to be irresponsible to our students.

The second thing I’ll say, which I shared with you earlier, is that here in Chicago there were a number of decades that a particular police precinct had been engaging in tortured confessions of young Black men, from the 1970s through the 1990s. A number of those young men ended up — one I became quite good friends with, Ronald Kitchen — ended up on death row. They were eventually exonerated and the city apologized, and all of this DNA evidence came to the fore to secure the release of some of them. But then it became hot as the city reckoned with this past. And one way would be to do a settlement with the families and call it a day, but activists pushed for an ordinance in the Chicago City Council. And they won! We won. And it was a Reparations ordinance, which included as a critical component that a segment in the high school curriculum in Chicago Public Schools be about this episode and ongoing practices in some circles of police misconduct. It was opposed by some people who said, “Why do your students have to learn about this?”

I think it has really been generative in terms of lesson plans and sensitive ways to broach difficult topics with young people. But many of the young people in Chicago Public Schools have had their own run-ins with the Chicago police and have been harassed. I’ve had family members who’ve been beaten up, I’ve had all kinds of bad things happen. So what better place than in a classroom to wrestle with and understand and dissect and explore how to change issues like police violence and state violence?

Hagopian: I just had the wonderful opportunity to interview Jen Johnson, the incredible union activist and teacher leader in Chicago, about that struggle for the Reparations curriculum, and I’m looking forward to sharing that with everyone in the new Black Lives Matter at School book.

So, we have another great question here from Robyn Spencer, who said, “What can be done to center those women that we’ve been talking about today in public memory? At today’s press conference in Minnesota, Fannie Lou Hamer was quoted. Otherwise, it has been Martin Luther King and Malcolm X on an endless loop. How do we get these women’s words, deeds, and examples out so they can be put to use today?”

Ransby: I think maybe in some of the mainstream press conferences, but there are many voices responding to this. This morning on Democracy Now!, Kandace Montgomery, who does Black LGBTQIA organizing as part of the Movement for Black Lives, was on MSNBC and they were invoking other legacies and political traditions, very much like feminist traditions, very much the Black radicalism of SNCC and the Black Panther Party, and so forth. So, I think we are always going to be up against the mainstreaming of the movement and movement history, always.

Interesting that Fannie Lou Hamer was mentioned, because often she’s left out as well. In organizing circles, certainly we are trying to push and present historical narratives that then people will draw upon when they’re in the thick of struggle. Scholars for Social Justice is a group that I work with, along with Rising Majority and the Movement for Black Lives. We’ve done think tanks on racial capitalism, we’ve done planning think tanks on electoral politics, and we plan to look at the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and the National Black Independent Political Party as well as others. I think insinuating in, intervening in political education in movement circles, and giving the sense of this rich history as what we do in the downtime, and hope that that shows up in these moments of intense struggle.

But, I assure you, many of the activists in Minneapolis had been the students of Rose Brewer, longstanding organizer with the World Social Forum, with the Black Radical Congress and Project South and others who have a sense of that history. It doesn’t always show up in the media snapshots. I think there’s a real struggle in Minneapolis now, as in many instances, where an intense struggle like this occurs of who becomes a spokesperson, and who is in front of the media cameras. This was an issue in Ferguson, it was an issue in Baltimore, and it was an issue throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Sometimes the personalities that the media gravitates to are not always the people who are doing the work on the ground. But I appreciate that question and I think there’s definitely a counter narrative. We may not be hearing it as loudly, but it is definitely there.

Hagopian: Thank you for that reminder. I think it invites people to really go further than what the media is presenting us as who the leaders are, and for us to look at how, in so many cities across this country, Black women are taking up key leadership roles that are propelling the movement forward, both ideologically and in day-to-day organizing.

There’s another question here from Jessica. Maybe just I’ll read this and then if you have a response to it, or any last thoughts, but we do need to wrap up in just about a minute. But, Jessica says, “How can we leverage what we have learned from the Combahee River Collective to honor and center the lives of Black trans and differently-abled women and Muslims?”

Ransby: I think that there’s a kind of mainstreaming of the Black Freedom Movement that centers King, for example, and leaves out women. Then there’s a kind of mainstreaming of Black feminist history that doesn’t include folks who’ve done disability rights work like Harriet’s Daughters, that exists now, for example, working with Black disability activists and others. I think always having that notion, that bell hooks notion of margin to center I think is really critical. Not only including Muslim women, trans women, LGBT women, but also incarcerated folks, incarcerated women, and formerly incarcerated women. Those women have been outspoken in this COVID period to the National Council of Formerly Incarcerated Women. I mean, that’s the task to always be mindful of, to anchor ourselves in principles that remind us and to surround ourselves with people, both colleagues and comrades, that remind us of the power of radical inclusivity.

Hagopian: Excellent. That’s a great way to bring us home. I want to just say thank you so much, Barbara, I learned a lot today. It has been inspiring and just what I need in these difficult times. Thank you.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

Here are many of the resources recommended by the presenters and also by participants in the chat box.

|

|

Books by Barbara RansbyElla Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision Eslanda: The Large and Unconventional Life of Mrs. Paul Robeson Making All Black Lives Matter: Reimagining Freedom in the 21st Century. |

|

Related BooksAmplify: Graphic Narratives of Feminist Resistance by Norah Bowman, Meg Braem, and Dominique Hui A Black Women’s History of the United States by Daina Ramey Berry and Kali Nicole Gross Florynce “Flo” Kennedy: The Life of a Black Feminist Radical by Sherie M. Randolph Freedom’s Teacher: The Life of Septima Clark by Katherine Mellen Charron Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC edited by Faith S. Holsaert, Martha Prescod Norman Noonan, Judy Richardson, Betty Garman Robinson, Jean Smith Young, and Dorothy M. Zellner Haymarket Books Against Policing & Mass Incarceration (list) How We Get Free: Black Feminism & the Combahee River Collective by Keeanga Yamahtta Taylor Making Face Making Soul/Haciendo Caras: Creative & Critical Perspectives by Feminists of Color edited by Glora Anzaldua Sisters in the Struggle: African American Women in the Civil Rights-Black Power Movement edited by Bettye Collier-Thomas and V. P. Franklin This Bridge Called My Back, Fourth Edition: Writings by Radical Women of Color edited by Cherrie Moraga and Gloria Anzaldua This Bridge We Call Home: Radical Visions for Transformation edited by Gloria Anzaldua and AnaLouise Keating Words of Fire: An Anthology of African-American Feminist Thought edited by Beverly Guy-Sheftall |

|

|

|

PeopleRose Brewer | Mandy Carter | Septima Clark | Angela Davis | Erica Garner-Snipes | Ericka Huggins | Mamie Till Mobley | Pauli Murray | Gloria Richardson |

|

|

OrganizationsBlack Lives Matter at School | Black Mamas Bailout | BYP 100 | Combahee River Collective | Harriet’s Daughters | Project South | Scholars for Social Justice | Southerners on New Ground |

|

|

FilmsStanding on My Sister’s Shoulders Documentary film on women in the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi. |

|

Articles and StatementsCombahee River Collective Statement “The Combahee River Collective Statement is a wonderful text to use in your classroom, particularly paired with the 10 point platform from the Black Panthers,” — session participant Andre Gilford “I am one dedicated person working for freedom”: Septima P. Clark’s Contributions to Social Justice Adult Education at Highlander Folk School by Lisa Baumgartner It’s Time We Celebrate Ella Baker Day by Mark Engler |

||

LessonsBeyond Suffrage: “A Unifying Principle” Understanding Intersectionality in Women’s Activism Primary documents with exploration and discussion questions, from the Museum of the City of New York Teaching SNCC: The Organization at the Heart of the Civil Rights Revolution by Adam Sanchez. A series of role plays that explore the history and evolution of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, including freedom rides and voter registration. Women of the Day by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca. A high school teacher looks at how a daily activity focusing on the representation of women helped transform her classroom. |

||

PoetryPoem About My Rights by activist June Jordan. The poem “is a masterclass on inter-sectional and anti-imperialist thinking,” — session participant Robyn Spencer |

||

|

Digital CollectionSNCC Digital Historical materials, profiles, timeline, map, and stories on organizing by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and connections to today. |

|

Participant Reflections

Here are some of the responses by participants from the session evaluation.

What was learned

Responses to the question: What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today and what may you do with what you learned?

“Need to transform the narrative, not just add color” — make sure to include the voices and experiences of all people, especially those typically underrepresented, but make sure that the narrative changes too, not just adding people in to say you are including different groups.

Love the quote about the “larger ecosystem of Black power organizations,” the way that Black women’s resistance fits into that ecosystem, and the connections to past Zinn Education Project Friday sessions.

I loved learning about Ella Baker’s role as a “movement teacher,” who advocated for a different vision of both education and leadership. The idea of distributed leadership and democratic education are ones that resonate with my hopes for my own pedagogy.

All of it, I had an extreme knowledge gap.

I was made especially aware of the gaps in my curriculum when I teach my 5th and 6th graders about the Civil Rights Movement and Black activism/organizing when it comes to including the work of Black feminist organizers.

Loved the idea that our current language had expressions in the past, just with less fancy terminology and I liked the idea that we should not “fetishize” youth — respect them but note they, like us, are on a continuum.

I liked the discussion on intersectionality between Black feminism, anti-war, and anti-capitalism and how we can connect past movements with today.

Chicago Public Schools reparations curriculum.

So much. But I cherish the comments about being your authentic, situated, political self in the classroom.

The recognition that Black Lives Matter is the first mass movement actually anchored in Black feminism. I will want to read her book to understand this deeply and bring it into my work with LGBTQ elders.

How many activists were also teachers – Mamie Till.

I learned about a great number of books and films that can be used to teach about intersectional Black feminism. Thanks. Didn’t know about Mamie Till’s (I didn’t catch her married name) ongoing activism.

Grassroots efforts of self-taught Septima Clark and philosophy for activism by Ella Baker. I will integrate these concepts into my 6th grade history curriculum.

I’m left thinking about the the brave choice many Black women make to allow their personal grief and pain to become public and politicized as a means of provoking change so that other Black folk don’t have to experience similar grief and pain. I feel like there’s a connection between the way the public and private intersect in these critical moments and the focus on intersectionality Black feminist leaders have gifted us, but I’m not sure how or what that connection is yet. This was a great experience. Thank you!

I was really struck by learning about the complexity and power of Ella Baker’s pedagogical approach to movement building/teaching. Paulo Freire’s work was always what I learned about (in graduate school and beyond), but I really want to study Baker’s approach and philosophy. I also was reminded about the power of study groups and smaller collectives to do the self-education that is needed to fortify and train ourselves to do the different levels of work we need to engage in (to strengthen and heal ourselves and to create a liberated society).

Mamie Till was a community organizer. I knew her choice to make Emmett Till’s funeral open casket and the media coverage of those images were intentional and very important to creating national discourse and outrage, but had never heard of her spoken as an organizer beyond reference of that one choice.

The format.

The format continues to be a great way for me to learn and grow.

The polling was really interesting, and interactive. Definitely the most engaging kind of big Zoom session I have been to so far.

The breakout groups worked and I am so grateful that for the past three times, I have had a facilitator in the classroom, which was really awesome! I love breakout rooms because, as a college student, I am exposed to teachers, professors, and other educators who influence how I hope to teach my future classrooms and have resources for me! The length of time was just right, the breakout groups didn’t have too many people, and the inclusion of photos was apt.

Jesse and Barbara connected brilliantly. Breakout group worked much better than I expected.

I think this worked well. I particularly liked to un-mute and thank each other for a moment at the end.

Never enough time for the breakout rooms, but it works in the time allotted for these sessions and on my own working calendar

It’s great overall. The breakout groups could be slightly longer, and it might be useful to include some brief exercises, such as presenters sharing stimuli then inviting participants to share how they would/could use them in their classrooms. This would provide a way for teachers (who usually make up the majority of participants) to share ideas and get feedback from experts.

Breakouts add always too short — excellent participation in #13 so we needed five minutes more! Whole seminar is too short . . . such rich info!! Sometimes hard to catch all the names the speakers throw out. Any chance for split screen with info on a PowerPoint? I can’t follow the chat quickly enough!

Have been in all sessions — it is something I look forward to each week. Self-quarantining can become quite frustrating. It helps with both little grey cells, a sense of positive struggle, and enjoyment just hearing the wide range of locations that the participants come from. It’s a reminder — we ain’t each alone, there is a broader community out there than what we see from our individual windows.

Excellent, great facilitation and seamlessly overcoming technical problems was very impressive. These are the best web classes I have ever attended.

Loved the format, discussion . . . the breakout group always seems a little short to me too, but I understand. It was so inspiring to listen to Barbara speak. Love that the Zinn Ed organizers are also thinking about creating community on the call, it is palpable. And while I sometimes personally get distracted looking at the chat during the discussion, I think that is very important for the spirit of community developing on these calls.

First of all, this was great and I am so glad to be connected and signed up for future sessions! I loved hearing Dr. Ransby speak! The perspectives of my breakout group were very interesting! As an elementary teacher, I’m used to speaking with other elementary teachers, so to hear from those in other roles was interesting.

I really enjoy the format. The large group lecture is always fast paced and engaging and the breakout rooms are lovely opportunities to meet inspiring people in the ZEP network. I am so grateful to the facilitators for helping us get the most out of the time!

Breakout session was short, but the size of the group was perfect. Greatly appreciated the connection to what is happening today. It further reminds us that even in the worst of days, there has been light and movement forward. May it happen again and soon. Barbara, you were an excellent and inspirational presenter. Although you helped me face the reality about how much I don’t know about our history, you also shared details about the work and strengths of these feminist warriors that will never be forgotten.

Happy to see one of my students in same breakout room; facilitator was helpful in keeping the conversation going; meeting like-minded from around the nation.

Additional Comments

Thank you SO much for doing this and encouraging so much participation. These are awesome and so glad I came across the Zinn Ed Project on Twitter.

Your online programs are well organized, peopled by wonderful experts, fascinating and important — awesome.

Thank you. This series brings magic to my Fridays.

These sessions have been causing me to think about starting something in my local area. Beyond union membership, I’m in conversation with colleagues to start a teacher-activist group that centers the voices of our students of color. I appreciate all the resources and materials to help make that possible.

This was my first session of People’s Historians Online. I am HOOKED and will pass on this valuable resource to many. In Solidarity and Love!

THANK YOU! This series has been both a balm and light for me in these past few weeks/months.

Thanks to the facilitator of the breakout room!

So grateful for a room full of women (which was a first in my breakout groups) during this particular topic — from a high school senior, to a preschool teacher, to a middle school teacher, to a graphic designer — it was really just so wonderful to engage with these other folks. I was so excited that the high school senior learned and was inspired by the Combahee River Collective today — what a powerful influence y’all are having on her life through that.

Thoughtful, timely, and so important. I’m working hard to unlearn + learn the things I was never taught so I can be better for my students. These sessions are incredibly helpful.

Much appreciation to Zinn Education Project for the amazing compendia of resources. Political education and community is how we get through.

I am so grateful for how all the information today, and the Black Freedom Struggle sessions have built and intertwined over the last few weeks. Thank you for giving us the background, and the resources for liberatory conversations with teachers and students! Here’s to centering Black Feminists in future instruction!

One of the great things about these events his how wide a geographic spread we have together via ZOOM. Thanks to Zinn Education Project, et al!!!

Presenters

Barbara Ransby is an historian, writer, and longtime activist. She is a Distinguished Professor of African American Studies, Gender and Women’s Studies, and History at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). Ransby is author Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision, Eslanda: The Large and Unconventional Life of Mrs. Paul Robeson, and Making All Black Lives Matter: Reimagining Freedom in the 21st Century.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, and editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn