On July 10, the weekly People’s Historians Online mini-class featured a conversation with historian Manisha Sinha and high school teacher Adam Sanchez about the abolition movement and Reconstruction. The session addressed themes of our campaign to Teach Reconstruction.

On July 10, the weekly People’s Historians Online mini-class featured a conversation with historian Manisha Sinha and high school teacher Adam Sanchez about the abolition movement and Reconstruction. The session addressed themes of our campaign to Teach Reconstruction.

Sinha stressed that the abolition movement should not be taught as a collection of individuals, but instead as a radical social movement. Here are just a few reflections from participants on what they learned. (More reflections at the end of this page.)

I learned about the magnitude of the abolition movement, which made me think more about how I’ve been taught it through the stories of a few huge figures. Another takeaway is that what is missing from subsequent social movements (post-Reconstruction) is a clear commitment to Black equality.

I need to show how large the abolition movement is. If I stress the involvement of many (including small towns, etc.), my students will be better able to see themselves in the movement and act today.

The large number of people involved in the abolition movement and their role before and after Civil War, including moving forward on schooling and economic equity after emancipation.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Adam Sanchez: Welcome everyone here, it’s great to see some familiar faces. On behalf of the Zinn Education Project, welcome to our session on abolitionists and Reconstruction. This is our last session in the spring series on the Teach the Black Freedom Struggle. We’re going to post a poll to see how many of you have attended all the sessions and how many of you are here for the first time. While you’re responding to the poll, I’m going to just introduce myself.

I am a high school teacher in Philadelphia and an editor of Rethinking Schools. Rethinking Schools coordinates the Zinn Education Project along with Teaching for Change. I helped to launch the Teach Reconstruction campaign for the Zinn Education Project and edited the book, Teaching a People’s History of Abolition in the Civil War, which, I should mention, Manisha has a short, student-friendly piece in.

The Zinn Education Project is hosting this session today and offers free downloadable people’s history lessons that many of you have used for middle school and high school classrooms, from the Zinn Education Project website. We have a campaign to teach about Reconstruction that people should look at, [and] there are several lessons and resources on the website for that campaign. Let’s take a look at this poll. It looks like we’ve got 70% of people who have been in multiple sessions. That’s excellent. About 20% of people are here for the first time. And about 10% who have been to one session. Okay, that’s great that so many people have come to so many of these.

So, we thank everyone who’s joining us today for the last session in the spring series on Teach the Black Freedom Struggle. We’re looking for funding. We’ve got some leads to continue this series in the fall, and we definitely hope to do that. So, throughout the session, we want you to use the chat box, post questions, comments, resources, [and] ideas. Our guest speaker will read your questions and try to respond after the breakout groups. We’ll do a short evaluation at the end, as well.

So, we’re now going to start our conversation, and after about 20 minutes, we’ll pause so that you all can meet each other and talk and reflect on the conversation in small groups to share insights. I’m really happy to be here facilitating this conversation and I’m going to introduce Manisha Sinha. She is the James L. and Shirley A. Draper Chair in American History at the University of Connecticut. She is the author of multiple books, and editor of multiple books, including The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition, which is such a crucial history of the abolitionist movement.

So, I’m just going to kick it off and jump right into it with a question for Manisha. Although this session is focused on Reconstruction, I’m very interested to hear, Manisha, your thoughts on Reconstruction, because that’s really where your book leaves off. I do want to start the discussion, though, by talking about the pre-Civil War abolition movement. We’re living through one of the greatest rebellions in the long Black Freedom Struggle and I think a lot of activists and thinkers who are thinking about the system today — of mass incarceration and the police as the frontline enforcers of that system — they’re looking all the way back to the abolitionists. In many ways, this was one of the first great social movements of the world. Yet most of my students, both in Philly and New York and Portland, Oregon, where I taught before, although they may have heard of one or two abolitionists, they don’t understand this as a movement that led to the freedom of enslaved people. I think the typical narrative that my students come in with in the classroom is “Yeah, there were some great people, Harriet Tubman, for example, who saved a few people, but ultimately it was Abraham Lincoln who freed the enslaved with the Emancipation Proclamation.” So I’m hoping you could start by talking about the role abolitionists played in ending slavery, and what are some of the lessons you think we could learn about today from that social movement?

Manisha Sinha: That’s a great question, Adam, because I have noticed, of course, that most people today are not aware of the fact that we had an interracial radical social movement like abolition in the 19th century, and even earlier, in the 18th century. And one that was actually quite successful in its short term goals. Even today, you’re right, when activists think about contemporary problems and contemporary oppressions — whether it’s mass incarceration or the fight against systemic racial inequality and police brutality — they look back at the abolitionists. And they use the term abolition.

You will notice that the term abolition is resonant with American activists and radicals, and there’s a reason why that is. Of course, the great Howard Zinn himself, when he wrote about SNCC, looked back at the abolitionist movement. And many civil rights activists saw themselves as, quote The New Abolitionists. They demanded a second Reconstruction of American democracy. And maybe, right now, we are ready for a third Reconstruction of American democracy, given the Movement for Black Lives and the upsurge in protests that we have seen this year.

Now, in terms of understanding the movement, I think, historically, in the mainstream academy, abolitionists had been neglected. And why? You have the Lost Cause mythology of the Civil War, that somehow Southerners had fought for states’ rights and their own honor, and not for slavery. You simply had very caricatured pictures of the abolition movement. You would have abolitionists being portrayed as these radical fanatics who were inconsequential, who had no influence on politics. That changed a little bit during the civil rights era when historians like Zinn and others started looking back at history and started looking for precursors to the Civil Rights Movement.

But when I started writing my book — which was, oh my god, over 10 years ago — even in the mainstream academy, I think people did not really appreciate the radical nature and the significance of the abolition movement. Many times they were seen as racially paternalistic or economically conservative. And while there were books on African Americans and women in the movement, there was no attempt to look at the ways in which these groups had maybe led and defined the movement. So, what I tried to do in my book, and what I tried to tell people when they teach abolition, is not to teach it as simply the stories of individuals — even though you’re right, there are outstanding individuals that we now all know. Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, there are so many like them. We need to think of them exactly the way that you put it, which is as a social movement, as a radical social movement that had certain tactics, ideologies — certain differences within the movement over those tactics and ideologies, but really one that eventually shaped the course of American democracy.

Sanchez: Thanks so much. Just a follow up on that one, one of the things that I think really struck me reading your book is how you’ve unearthed and re-emphasized the critical role that Black abolitionists played in pushing white abolitionists to take more radical stances and move to more confrontational tactics and things like that. Could you talk about that a bit?

Sinha: Yes. Before I wrote this book, of course, there were many books that had been written on African American abolitionists. The great Benjamin Quarles had written the first complete monograph on Black abolitionists, and his whole purpose was just to prove that they were part of the movement, because they had been so neglected by mainstream historians. So I definitely wanted to highlight the role of African Americans as being in the vanguard of the movement, as not just people who participated in the movement, but people who actually thought of many of its ideas and tactics, and who radicalized the movement.

For instance, the abolition movement, especially of the 19th century — the period just before the Civil War, in that moment when African Americans are taking on leadership roles, they’re lecturing agents. As they’re very much part of that movement, they make sure that the movement is not just to end slavery, but that it is also a movement for Black equality, and for Black citizenship, equal citizenship in this country. So they attack southern slavery, but they also attack discrimination and segregation in the north. It’s really important to uncover the significance of African Americans in the movement in that respect, because they’re really laying the groundwork for Reconstruction.

When abolitionist jurisprudence, when they’re using the Bill of Rights to fight for Black people’s rights, or arguing that we should have a national standard for citizenship, they’re laying the groundwork for that brief moment during Reconstruction when you have an interracial democracy. And that all comes from Black activists. And white abolitionists, like Garrison, are quick to adopt that program. They’re quick to adopt the program of citizenship. They reject this program of colonization, of sending free Black people back to Africa. Instead, they argue that the fight for Black rights has to be in this country.

So I did that. But the part that I think was somewhat unique to my book, was to look at not just free African Americans, but also enslaved African Americans. After all, 90% of the Black population was enslaved before the Civil War. So it was really important for me to highlight the role of slave resistance in the abolition movement. And if you look at the leadership of the abolition movement in the 1840s and 50s, it is composed of these outstanding fugitive slaves, all these runaways like Douglass, Harriet Tubman, William Wells Brown, James W. C. Pennington. I mean, there’s so many of them, I could just keep going on. They really assume a dominant role in the abolition movement. So I really wanted to look at the ways in which slave resistance, broadly understood — not just as instances of slave rebellions, even though I cover that — but also the ways in which enslaved people themselves fed into the movement and radicalized it by introducing tactics, opposition, say to the Fugitive Slave Law on streets that were far more militant, than in previous years.

Sanchez: And I want to add, this was one of my follow up questions, but I also see a question in the chat. Could you talk specifically about the role of Black women abolitionists and the role they played in the movement?

Sinha: Absolutely. African American women really take a leading role in the abolition movement. One of the first female anti-slavery societies was formed in Salem, and it was an all-Black society. It is only later on that they start admitting white women, so it becomes an interracial society. And when the abolition movement starts in the early 1830s, Garrison points out two white women and says, “Look at all these Black women. They’re forming these anti-slavery societies. You should imitate them and do the same, or join their societies.” So Black women play a very important part in this movement.

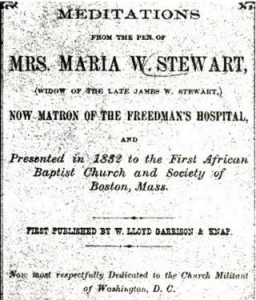

We also know, of course, that Black women played an important part of the movement. One of the first women to speak publicly to public audiences, one of the first American women to do so, was a Black woman, Maria Stewart. One of the first American women, not just one of the first Black women, but one of the first American woman to ever be published was a Black woman, Phillis Wheatley, with her book of poems that was published in England in 1773. This is when most white women did not publish anything. And if you look at Wheatley’s poems, many of them arguably had anti-slavery content. For a long time, they were dismissed as being too deferential or too much in the language and tropes that was adopted in mainstream Western literature at that time. But actually, if you read Wheatley closely, and not just her published work but even her letters — one of them was so famous that it actually got published in New England newspapers — if you read all her corpus, you’ll see that she was really in a way the mother of the abolition movement.

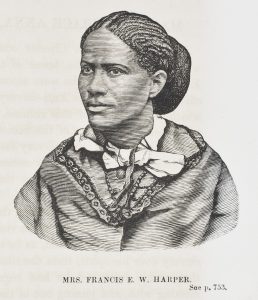

So, interestingly enough, Garrison, in the 1830s, re-publishes her book of poetry because he thinks they are so significant. Black women play a leading role, they play a pioneering role, in the abolition movement. And later on, of course, you have outstanding abolitionists feminists like Tubman, who was not just active in the Underground Railroad but was also a suffragist. But Sojourner Truth and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, whose speeches were the sensation of the abolitionist circuit. Harper was so good that she was employed as the main lecturing agent of the main anti-slavery society. And trust me, they will not allow Black people in Maine, and many times she was going to towns where she was the only Black person around. So I think it’s important, in fact, to recover the relatively forgotten role of many of these Black abolitionist feminists, because we often think of suffrage, we often think of feminism, as a white woman’s project. And it’s not true if you look at many of these outstanding Black abolitionist feminists.

Sanchez: So fascinating. Just one more question before we transition to the Civil War and Reconstruction. I’ve looked a lot at different textbooks and what they say about the abolitionist movement, and many still parrot what you had said earlier that the scholarship did. But the abolitionists were this small band of radicals that didn’t really have that much political influence. And they highlight a few fanatics, as they might call them, but really the key thing is that they still portray them as a very small movement. I was always struck because a lot of pictures I had of the abolitionist movement, when I learned that the American Anti-slavery Society had over 1,300 local chapters in what was a much smaller United States at that point, I just think if you had 1,300 Black Lives Matter chapters in this country meeting on a regular basis — I’m not even sure that we have that right now. So, if you could talk about the size and scope of the movement, especially leading into the Civil War.

Sinha: That’s another very good question. Because you’re right, that’s the way textbooks generally tend to deal with the abolition movement. It’s a tendency not to give importance, perhaps, to people who probably were more influential in shaping the course of American democracy in the 19th century than many prominent senators and presidents, even. Some of them are highly forgettable, the ones of the 19th century. So, that is why I use the perspective of a social movement. I thought it was important, in fact, to look at the way in which the movement came about, how it organized itself. So if you look at abolition, they’re kind of old fashioned moralizers sometimes, like Douglass, who can quote chapter and verse from the Bible, etc., to fight against slavery, or invoke the golden rule to fight against racism. But they were very modern in certain respects. They had an amazing print culture; they had many pamphlets and newspapers; they had organizations, as you mentioned, over 1,000.

In fact, we have an undercount. Because, as I was researching my book, I would find tiny little anti-slavery societies in some forgotten New England town, which sometimes didn’t even show up in the records. So they did really spread out in the north, into rural hamlets everywhere. In fact, the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020, I noticed in my small town in New England there was a protest, and it made me think of the abolition movement because that’s how much it had spread, even into smaller towns, into rural areas in the north. And in terms of numbers, James Birney, the Secretary of the American Anti-Slavery Society, just guessed at around 250,000. But that was just to guess. If you look at the numbers that had signed petitions, you’ll get hundreds and hundreds, thousands. Then if you look at people who just participated in one campaign or the other, you get many more fellow travelers. So abolition actually was far more widespread, I think, than we have understood it until now. It’s difficult to get the exact numbers. I tried to make those numbers clear in my book when I talked about the anatomy of the movement.

We know, of course, that abolitionists were also politically significant, because they first started their own political party, the Liberty Party, which made anti-slavery a factor in national politics. That was the precursor to the Free Soil Party of 1848, and eventually the anti-slavery Republican Party in the 1850s, when you have, of course, the rise of Lincoln. That’s the last time the third party has been successful in the history of the United States. They go from being founded in 1854, to winning a presidential election in 1860. That doesn’t just happen. Abolitionist activists had plowed that ground for decades, since the 1830s. So when the Republican victory comes about, it is important, in fact, to understand that abolitionists had played a crucial role in preparing the Northern public, or the majority of those northern white men who voted for the Republican Party, which led to secession and Civil War.

As far as Lincoln is concerned, in the Emancipation Proclamation, he’s quite clear, he actually says, “the abolitionists thought of all this before me, they should get the credit.” He actually says that, and I was able to get that quote. Now he mentions [William] Wilberforce and Garrison, the white abolitionists. He doesn’t mention the Black abolitionists. But where does Garrison get many of his ideas from? From Black abolitionists. So I think it is important, in fact, for our school textbooks, and the ways in which we teach the histories of slavery and abolition, to emphasize the history of the movement. Because the tendency is to think of Emancipation as a gift handed down to Black people, when it was not that. It was not that before the war, and certainly not during the war, when enslaved people did pretty much what they had been doing before the war, which is to seek out free spaces and allies in their fight against slavery.

Sanchez: Could you talk a little bit, this is kind of just where you left off, about the role that abolitionists played during the Civil War, and in particular, in conversation with Lincoln, who moves significantly, I think, during the Civil War in terms of the way he thinks what the war aims are, and so forth. What role do the abolitionists play in that?

Sinha: I ended up writing a number of essays on this issue because of the Lincoln bicentennial, and President Obama was elected and used the Lincoln Bible. There was so much going on with trying to think about Lincoln’s legacy. I look very closely at his relationship with the abolitionists, because the debate over emancipation amongst historians had really been [about] who freed the slaves. Was it Lincoln or was it the enslaved themselves, who saw Lincoln and the Union Army and the federal government as their liberators before they saw themselves in that role by simply fleeing to Union Army lines and forcing the army, because of logistical reasons and the government because of political reasons, to deal with the issue of emancipation. So that was the debate. And I argued, in many articles that I wrote on this issue — which eventually I incorporated some of it into my book — that we need to understand emancipation as a process. And one of those forgotten historical actors in the history of emancipation were the abolitionists.

If you look at what abolitionists do immediately after Lincoln was elected, they started pressuring him and the Republican Party. They’re pressuring them from within, because the radicals in the Republican Party, like Charles Sumner and Thaddeus Stevens, are completely aligned with the abolitionist movement. They’re abolitionists themselves. They’ve been involved in the battles against slavery before the war, and they’re used to abolitionists gaining an insider’s edge when the Republican Party is elected. That’s not normally understood that way. But if you were to draw a Venn diagram of the Republican Party and the abolitionist movement, the radicals would be the people in the middle. The radicals, they’re not literally in the middle because they’re left of the Republican Party, but that overlap of those two circles would be Radical Republicans, and they really do bring the abolitionists agenda in Congress. They move before Lincoln with the Confiscation Acts and making sure the Union Army does not return fugitive slaves back to rebel slaveholders. So yes, they play an important part, even in terms of persuasion, which is what they’ve been doing all the time before the war.

When Lincoln starts flirting again with colonization schemes, they rebuke him. One of the best rebukes of Lincoln actually was written by a Black woman. Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, she wrote an essay saying that this is the most ridiculous plan in the middle of a war, when you actually need people to be fighting against slavery, to think about expatriating them back to Africa, or any other place in Central America that he was experimenting with, it was the wrong thing. So both Black and white abolitionists, I think they’re an extremely important part, actually, in pushing for emancipation, and pushing that process forward.

Sanchez: So important. Alright, let’s move to Reconstruction. Can you walk us through what happens to the abolitionist movement after the war? Because I think this is something that’s often completely left out of the textbooks and mainstream accounts. As if all the abolitionists say, “We won,” and they go home. Do they move on to fight for other causes? Does the movement splinter? Do different sections of the movement define freedom differently? What happens after the War?

Sinha: During the war itself, abolitionists were forming Freedmen’s Aid Societies. They were forming Emancipation leagues, and all these other societies to address the problem of what’s going to happen after the war. How do we define freedom? African Americans themselves had a good idea about how they define freedom. There’s that famous conversation between Black leaders in Savannah, Georgia, with General Sherman, where they tell him clearly that for us, freedom means economic independence, it means equal political rights. They have a good idea about that. And they have good allies, with abolitionists who start founding the first schools. These are the roots of many of the HBCUs, going back to these Freedmen’s Schools being founded by abolitionists during the Civil War.

These Freedmen’s Aid Societies are an important precedent for the Freedmen’s Bureau during Reconstruction, which is a federal government agency that was supposed to oversee the transition from slavery to freedom. So abolitionists are already anticipating the problems of Reconstruction. Now, the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1865, Garrison says, “Look, I’m done, because I think the momentum for change has moved to the government.” It’s not that he says, “I don’t support Black citizenship, and now that we have Emancipation, my work is done,” because he always believed in fighting for equal rights of Blacks as well. A lot of people misunderstand that. But he says, “The American Anti-slavery Society as an agitational tool is pretty much done. Now, we should be looking at practical things like Freedmen’s Aid Societies, working with the government, etc.” And Phillips and Douglass tell him no. They said, “Unless we get an amendment to the Constitution that actually guarantees Black citizenship rights, we are not going to dissolve the society.” And Garrison knows this. Phillips and Douglass actually win and the society continues.

Eventually, in 1870, when the 15th Amendment to the Constitution, giving Black men the right to vote is barred, Phillips and Douglas say, “We are done. Now we are going to disband the American Anti-slavery Society,” and the other radicals say, “No, our work is not done. Because land has not been redistributed as yet to Black people. The promise of Reconstruction has not been fulfilled.” So these debates continue within the abolition movement.

Now, Phillips and Douglass win the debate, they could have imagined that Reconstruction will be completely overthrown, that all those constitutional amendments will be completely overthrown in the South through a regime of racial terror, and also legal conservatism, with the U.S. Supreme Court pretty much overthrowing and narrowly interpreting these amendments and laws so that it was easy for southern states to discard them and to establish a regime of Jim Crow. And all the results, the victories of the abolition movement, are frittered away.

I read some abolitionists memoirs after enduring Douglass’ last autobiography after Reconstruction is overthrown, and the fight never ends. We fought all this, we thought we had reached the promised land, and now we are back here. It all feeds into new protest movements into the turn of the century and early 20th century, with many descendants of abolitionists, including Black activists who really identified with and admired abolitionists, and admired the Radical Republicans who had instituted Reconstruction, like Du Bois, ended up founding the NAACP to renew the fight for Black rights. So in a way, the abolitionists legacy encompasses Reconstruction, but it goes beyond that. The idea, as I say in my book, the same sports never dies. The reason why I say that is because it seems that that contestation for Black rights is a never-ending project in this country.

Sanchez: One of the other things I wanted to ask you, I think so often the textbooks kind of jump from the Civil War to these debates within Congress and the president, and then the backlash against Reconstruction, and skip over this tremendous moment of interracial democracy. As you said earlier, in particular with regard to social movements at the time, before the 15th Amendment, but after the war, it seems like there’s this moment for a few years where different social movements are inspired by each other, they’re feeding off each other. They’re to some extent collaborating, right? In particular, the labor movement, the women’s movement, and the abolitionist movement. The American Equal Rights Association was founded, bringing together abolitionists and women’s rights activists. The National Labor Union is discussing opening its doors to Black and female workers and activists. Could you talk a bit about this moment, because I think it too often gets skipped over, and what can we learn from it?

Sinha: Absolutely. I think Reconstruction was a moment of great possibility in this country. As many times in American history when we’ve had dramatic progress in Black rights, it feeds off other movements’ rights. The same thing happens with the Civil Rights Movement, with the rise of second wave feminism, Native American rights, and many other movements that kind of feed off this fight for Black equality. I think Du Bois said it best, and that was the fight for Black equality was not just something that would benefit African Americans themselves, but that it would redefine American democracy as a whole, because it inspired radical imaginations, it inspired all these other movements.

And you’re right, during Reconstruction, there’s a lot of experimentation with wanting to do more than just have political and civil rights. Whether land redistribution or feminists fighting for women’s right to vote, it seemed like a moment of endless possibilities, precisely because there was this moment of interracialism. And after the fall of Reconstruction, you still have the rise of other movements — you still have a suffrage movement, you have a labor movement, you have a temperance movement, you have the populist movement, the farmers revolt. And some of them do make overtures to African Americans, like the populist movements and the Knights of Labor in the beginning. Then later on, of course, when you have other labor unions coming up, like the International Workers of the World, the IWW, they do make overtures to African Americans, and they often fight in laborers fights throughout the country, which are interracial and sometimes successful.

But what’s missing in many of these movements after the fall of Reconstruction is a clear commitment to Black equality. You see that in the suffrage movement, you see that in the labor movement, you see that in the populist movement later on. Black people get forgotten, and that becomes the Achilles heels of not just American democracy, but even of progressive movements. Because many times, for instance, the suffrage movement, which I’m looking at right now, in order to appease southern white women, they decide okay, we can have segregated [illegible]. We don’t have to talk too much about lynching or the racial terror in the South that Black suffragists like Ida B. Wells is talking about. So, it is really important for us to learn the lesson, especially for grassroots radical movements on the left, that the fight for Black equality is really central to any sort of reimagining of American democracy. We see that even today.

Sanchez: I just want to briefly mention a few lessons. We actually have a lot of lessons at the Zinn Education Project on abolition, the Civil War, and Reconstruction, so I can’t mention all of them. But I do want to mention just a few that are out there. This one on your screen is Who Fought to End Slavery? Meet the Abolitionists. It’s a great mixer roleplay where kids get to take on the role of one abolitionist and then they meet the other abolitionist in the room. We specifically wrote it to try and highlight abolitionists who are often not highlighted in the curriculum, as well as complicate some of the stories that kids have heard about the more prominent abolitionists.

Another really important lesson we have is ‘If There Is No Struggle…’: Teaching a People’s History of the Abolition Movement. This one has students write an autobiography of an abolitionist. They step into the role much deeper and then they go through a series of debates, and they lead that student-led discussion that the abolitionist movement actually went through in the lead up to the Civil War. If you haven’t done it in your classroom, I just can’t recommend it enough.

Poetry of Defiance is another lesson that highlights the resistance of enslaved people themselves. And there’s some really good ideas in that lesson for how to tie that to the abolitionist movement in the way that Manisha does in her book. Lots of great teacher testimonials about that as well. And again, please also go to the Teach Reconstruction campaign page, where there’s several lessons on Reconstruction, including the another mixer lesson called When the Impossible Became Possible that gets at some of the connections between the different social movements that begin to be made in the first couple of years during Reconstruction.

So, we’re going to continue a little of our discussion. I wanted to start with a question about David Walker, and the role he played in his appeal, David Walker’s Appeal. Where does he stand, I think the question was, in the pantheon of abolitionist heroes? So what can we say about David Walker?

Sinha: I think that’s a really good question. David Walker was so important because of his Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World. It’s really the first radical abolitionist pamphlet that is published 1829. The first Black abolitionist newspaper was founded in 1827, Freedom’s Journal. So Walker’s part of this rising militant Black abolitionism of the 1820s. It also coincides with many famous large slave conspiracies, like Denmark Vesey’s slave conspiracy in South Carolina. Walker was actually a free Black man from North Carolina, and was probably in Charleston when Vesey’s conspiracy took place, so you can see how slave resistance and free Black radicalism are really intertwined and flow together.

By the time [Walker] comes to Boston and writes this pamphlet, he’s part of the Massachusetts General Colored Association, one of the first abolitionist groups ever founded. His Appeal causes a national stir because it’s distributed all over the country by Black sailors, even in the South. And it makes many Southern governors very nervous because they think his pamphlet would lead to a slave rebellion. Garrison, when he starts publishing The Liberator, actually has the first few issues devoted just to David Walker’s Appeal. He praises David Walker’s Appeal.

By the end of 1831, you have Nat Turner’s rebellion, and Garrison is one of two editors in the United States who actually praises Nat Turner, even though he’s a pacifist. So Black radicalism — of which David Walker was an essential part — really flowed into the growth of the abolition movement. The second wave of the abolition movement was a radical, uncompromising movement by that time. And you could certainly say that many of the white abolitionists like Garrison got their ideas from African Americans, like Walker. Walker also inspired, by the way, Maria Stewart — the Black abolitionist woman whom I spoke about — was mentored by Walker. Unfortunately, he died early, but this interracialism that I talk about in my book, this chapter on interracialism that traces out all these connections. Walker’s widow names her son Edwin Garrison Walker, so she named him after Garrison because she sees Garrison as keeping his memory alive. And David Walker’s son becomes one of the first Black elected politicians in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. So he’s important. I think the full story needs to be told. I mean, one of the reasons I think the book is big is because even though people have heard of these figures, and they know about this one thing that they’ve written, they don’t know that much about them or their legacies. And I think it’s important to remember them, and Walker is certainly one of them.

Sanchez: Absolutely. Before we jump into the next question, I just want to share the results of the poll so people can see how many people have learned about this history. Less than half, I think, in most of these categories. So I hope this session has propelled people to teach more and to learn about it. There were a couple of questions about some of the tensions within the abolitionist movement. There was one about how many abolitionists were anti-slavery and anti-Black, and a question about teaching that. I’ll be honest, I don’t know that I do a deep enough dive into that question. I’m curious what you say about that, Manisha. And then also class differences, right? Why do some people have more equality than others? So if you could talk about those two things, both racism within the abolitionist movement, and how class differences play out?

Sinha: Yes, absolutely. It’s really important, I think, for us to distinguish the abolition movement as a radical social movement in which African Americans played a central role with political anti-slavery. When the abolitionist movement founded its party, the Liberty Party, it was an abolitionist party, but it had to take on other causes in order to be successful as a political party. Eventually, that became the Free Soil Party, and its platform was not even abolitionist. Its platform was just the non-extension of slavery into western territories. So, many Northerners joined the Free Soil Party, the Republican Party, who were not particularly liberal, when it came to views about Black equality and race. The radicals within the Republican Party, who were the abolitionists, were constantly fighting with the conservatives and the moderates, pushing them to take more abolitionist positions.

So first we must distinguish, as I said, between a radical abolitionism and political anti-slavery. Many times, we don’t, and sometimes people were anti-slavery at what I call the lowest common denominator of anti-slavery, which was, let’s just stop the expansion of slavery to the west. But we don’t really want to deal with ending slavery, abolition, or Black rights — that’s going too far. It’s really the Civil War, the revolutionary situation of a civil war, that pushes the North towards abolition. Then, eventually, it was Black rights during Reconstruction. Now within the abolition movement, there were times of racial paternalism by white abolitionists toward Black abolitionists. I was really pushing back against this literature, especially these historians, Jane and William Piece, who wrote a book on Black abolitionists and said Black abolitionists were really not effective at all because the abolition movement was so racist that they were on the sidelines, they had no influence in the movement. That was simply wrong.

So I really push back against this narrative that white abolitionists were amazingly radical compared to the average white American in the North. Forget the South at that point as a slave society, but in the North in the 19th century. But there still were times of racial paternalism. I’ll give you one example. It was not as if Black abolitionists just folded up and accepted it. They pushed back against any instance when you had what I would see as creative conflict. This is the one space of interracialism in Antebellum America which was a highly segregated society racially. But here Blacks and whites and men and women came together to debate issues and to talk about it. They were called “promiscuous societies” precisely for that reason. The incident that I’m talking about was Theodore Parker, a Unitarian abolitionist, a supporter of John Brown, who was involved in fugitive slave rescues, he gives a speech and he uses something that’s really popular in Anglo-American culture, that type which is the “cult of Anglo-Saxonism.”

And it pervades Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin too when he says, “Oh, Anglo-Saxons are really brave, and we are always fighting, and we would never be enslaved. The African race is more docile, because they’ve been enslaved for so long.” And he’s saying this in an anti-slavery movement. Immediately, John S. Rock, a Black abolitionist, jumps up and says, “This is racism. This has no place in an anti-slavery platform,” The cult of Anglo-Saxonism, which is, as I said, really popular, developed by the British writer, Thomas Carlyle in the 1850s. He says you really should not be talking about this and this is racism. What’s interesting is that the conversation doesn’t stop there. Parker gets up and apologizes and said, “You’re right. I misspoke.” For me, that’s how instances of racial paternalism were dealt with. And I have many other such instances in my book where I argue that this notion that somehow white abolitionists were irredeemably racist and therefore Black abolitionists were just sidelined and had no effect on the movement. It’s just ahistorical. In fact, it tells us more about the way we view the world, I think, than the evidence.

As a historian, I think it’s so important to go back and read those sources, because that’s exactly what I learned in graduate school while I was studying the abolition movement. So I felt when I was writing the book that I had to really go back to the archives and actually read. For me, the best challenges were what are African Americans saying? What is the Black abolitionist saying about this particular white person? And I found many instances in which historians had actually distorted many encounters, including the famous Douglass-Garrison break in the 1850s over politics and abolition. I deal with that extensively in the book. We don’t have too much time, so I won’t get into it right now, but it’s in my book, and I talk in depth about how that break occurs and why it occurs, and why we should look at it beyond simple racial terms.

Sanchez: I see a question in the chat about the PBS abolitionist documentary and I think it’s really related to this this question, because what really struck me when I watched it is that I think there’s four abolitionists that they feature throughout the documentary, four or five, and I think all of them are white except Douglass. I’m just curious what you thought about that documentary? What did they do well and what did they get wrong?

Sinha: I was one of the advisors or talking heads in that documentary, and I really didn’t want them to have just four or five people because I have this vision of the abolitionist movement as a movement and I wanted them to portray the movement, rather than just fixate on four or five individuals. But the writer for the documentary said that that’s the only way they could convey the story. They had only three episodes and they would do it. Then he told me the people he had chosen were Angelina Grimké, Garrison, John Brown, Douglass, and then Harriet Beecher Stowe. That really bugged me. I really fought with them about that. I said, “Harriet Beecher Stowe was not an abolitionist. She was in fact a colonizationist. Uncle Tom’s Cabin ends with George wanting to go off to Liberia. Her family was a family of colonizationists, and they had opposed abolition. So I said, “You can’t have Harriet Beecher Stowe. You have to have a Black woman.” I mean, it’s tough.

But I lost that battle because they would not agree to removing Harriet Beecher Stowe because they thought out the Uncle Tom’s Cabin had such a tremendous impact, which it did. But she was not an abolitionist. She became an abolitionist after publishing Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and that’s the part of the story they didn’t tell. Because Martin Delaney says, “I don’t like Uncle Tom. He’s just too broadly for me. No, he doesn’t represent us well.” And she takes his criticism to heart. So then she publishes her second book, which no one’s heard of, called Dred: A Tale of the Dreadful Swamp, which is a story of slave rebellion and defeat. The person Dred is very different than the image of the saintly Christian, suffering Uncle Tom. But you can see why Uncle Tom’s Cabin is the more popular book because it really appealed to white prejudices and white sentiments about race and slavery. That’s why it was in a way so effective, and then became this international bestseller. So I lost the battle, both in terms of getting a longer series about the movement and also by having at least one Black woman in it. Now, there was a lot of criticism of the documentary because of this, because of these choices that the writer insisted on making. And I felt that it still does more than what we had until then, which was like nothing on the abolitionists and I still think one could use it in the classroom with a proper critique of it. I still use it in all the teacher institutes that I do over summer with teachers, when I look at slavery and abolition, and I felt and talked about how we can use it, but with those criticisms, and putting it in that context.

Sanchez: I’ll say that, in particular, I think it’s the third part, where the Civil War begins, where they actually do take a step back from these individual stories and talk more about the interplay between the movement and Lincoln, I think that part in particular is useful in high school classrooms and has worked well with my students. But even so, as you said, you have to also go in with a certain amount of critique, because they do kind of make Garrison into this new white savior, in a sense.

Sinha: I think it’s really important to understand that you need to be able to read Garrison. We get what Garrison is saying. Garrison is not saying, “I’m here to save Black people.” He constantly says, “I got this idea from African Americans.” If you look at the early, you should The Liberator, it is completely suffused with African American ideas. And of course, African Americans are the majority of the subscribers. It’s really a Black newspaper; 450 out of the 500 [subscribers] are African American. So when he goes to Britain and he’s introduced a lot, Buxton, an anti-slavery politician, Buxton looks at William Lloyd Garrison and said, “I thought you were Black.” And Garrison says, “I’ll take that as the highest compliment of my work.”

Garrison has also been misunderstood. I think that when we get fixated on individuals, you get simple narratives of the white savior, et cetera. But if you look at the movement as an interracial radical movement where whites and Blacks were working together, learning from each other, confronting each other, sometimes even fighting with each other and debating each other, I think it’s a much more useful framework. It could be that I grew up in India and I’m not just so steeped in post-independence India, steeped in the sort of deep racialisms of the United States. I looked at many of these documents and said, “Well, this is about something else too.” I think Garrison has been quite misunderstood. I don’t look at contemporary takes on Garrison, even by scholars who have written now. I always judge these white figures by what contemporary African Americans are saying about them. What were African Americans like William Wells Brown, William Cooper Nell, Maria Stewart, Francis Ellen Watkins Harper, Douglass, Frederick Douglass’s famous eulogy for Garrison, what did that say about Garrison? Because they kind of knew him, [whereas] we can just speculate.

Sanchez: Well, thank you. We’re going to pause there. It’s been a tremendous conversation and I learned a ton. Now we want your feedback on this session, the content, and the format. We’ve put the link in the chat box to the evaluation, but before doing the evaluation, please, we’re going to ask folks to unmute yourselves and share thank you’s to each other for your commitment to learning and teaching people’s history, to our facilitators. We’ll be sending a follow-up email with the resources referenced here today. Thank you so much.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

Participant Reflections

Here are some of the responses by participants from the session evaluation.

What was learned

Responses to the question: What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today and what may you do with what you learned?

A crucially reinforced idea of abolition as a long, radical social movement, one with deep roots that trace back to pre-American Revolution (petitions) that endures to today, what Dr. Sinha or Adam referred to as the “current rebellion”. Banking on resonance of present day abolitionist movements (abolish prisons, abolish police, abolish schools, abolish racism in all its forms) to engage student curiosity about its long backstory.

I learned that the abolitionist movement was a large movement that spanned the country, not limited to a small radical group. Also, re-framing the idea that it wasn’t confined to a period but is a movement that is not finished! The resources are SO helpful for my history classes!

It was truly significant to learn about how instrumental Black women were in the abolitionist movement. I plan on bringing in narratives from abolitionists and the Reconstruction era into my ELA course.

Importance of Black abolitionists … I will focus on them for my teaching of U.S. history.

Affirmation! That Black struggle and liberation movements are at the center of all other liberation movements, from abolition in 1800s to today.

That enslaved people were a large part of the abolition movement.

The abolitionists movement was more widespread than what is presented in the textbooks

To continue to interrogate the racial ideas of everyone, here, more specifically of abolitionists. I will mention the Theodore Parker example as a way of saying “we are all — even dyed in the wool abolitionists — always, trying to purge ourselves of the inheritance of racial ideas.”

I learned more about the broader MOVEMENT of abolition — reminded me of Jeanne Theoharis’ comment about the “tendrils that lead up to a moment.” It was a good reminder not to stick to the same names that always get mentioned but to intentionally seek out the lesser known people involved in these movements.

I learned a LOT today! I appreciated the focus on African American abolitionists and the strategy/organizing/creativity of the movement! That Black abolitionists were establishing the basis for Reconstruction with emancipation leagues, etc. and also anticipating the problems of Reconstruction. The story of Parker was also really compelling/stands out as something I want to study in more depth. And I “met” Frances E. W. Parker! I can’t wait to read her work!

The history of abolition is a continuum that goes to the present! Some abolitionists have said they were “done” had achieved their goals at different points, and some (the more radical) keep going!

I’m inspired by thinking about how Black radical abolitionists laid the groundwork for Reconstruction. This idea presented by Dr. Sinha helps me consider cohesion to bridge antebellum America with Reconstruction in some really powerful ways. Also, centering female abolitionists remains an important thread to today’s Black Lives Matter movement.

Did not realize the size/scope of the movement. Will definitely re-frame teaching!

That the abolitionist movement was larger than discussed in most resources.

SO much to take back to my 5th graders! Distinction between antislavery and abolition movement; failure to center equality for BIPoC as Achilles heel of progressive movements; focusing on movements rather than individuals (pillar of white supremacy); pushback of Black abolitionists on white paternalism and meetings as opportunities for interracial debate, creative conflict, and growth — development of ideologies over time — model of Theodore Parker saying he was wrong!

Role of small abolitionist groups in many towns and the over all huge numbers of participants, especially as students grapple with what their role can be in our modern movements, reminding them that there is nothing unimportant in standing up for rights and what you believe in, small, big, local, national — all roles are important.

I also was reminded about how many individuals we know only the one quote from and learning more about their whole story rounds out their contributions and models how to fight for students.

Critiques of the PBS series The Abolitionists. I used to show it. If I do so again, I am better prepared to engage students in critiques of it.

The format

Loved listening and then being able to process in breakout groups and then come back.

Always wish these could be longer.

I love the format I have suggested it to many other groups that I have been working with.

I like the overall structure of the zoom. I’d like more time in the small groups. We just got started when time ended.

The breakout rooms could use maybe 5 – 10 more minutes.

Wonderful presenter, the breakout group was great but too short. Our facilitator was fabulous. I think teachers are desperate for interaction with other teachers! The chat box is so distracting, especially when one participant, as happened today, is using bad faith arguments to comment on the presenter and purposefully misunderstanding the information being presented. I did not allow myself to reply, but I couldn’t focus as the comments continued to come in.

Fantastic format! Although I always wish for more time in the breakout room!

Format is great. Twelve minutes is too short in breakouts. Or maybe have two shorter breakouts — one for each question.

This was my first session with a small group facilitator and while all my other groups have had great discussions, it was nice to have a leader who so openly and kindly invited conversation.

The format of scholarly speaker in conversation with a classroom teacher facilitator really works well to focus the presenter’s amazing and vast knowledge and insights with questions that will come up in middle/high school curriculum planning. Having ideas about where to attach these new people and stories into my required curriculum is so helpful in planning how to pass on all the inspiring things I’m learning.

Everything, as usual, was wonderful! I have so appreciated these Friday sessions. They’ve really been a bright beacon of community and learning in this dark time.

Additional comments

Appreciate what you are doing to help us change the narrative regarding what is being taught in schools.

Thank you. This series has been incredible for me as a learner and a teacher.

Y’all are amazing. I appreciate your intellectual, emotional, spiritual labor with this work. Gratitude.

Thank you! I’m looking forward to going back to watch sessions I missed, and I hope there will be more.

I say this every week, I think. This opportunity every week has been so powerful for me as a learner, a teacher, and a person. You have created a space where the facts and the history support solidarity on a daily basis. I have been truly blessed and in some ways, carried through the last few months by the community that has gathered here. Deep thanks!

Thank you, thank you, thank you to all the presenters, leaders, facilitators and the Zinn Education Project team for making this series. It has been a highlight of the spring/summer and so helpful for keeping motivated and connected to amazing educators through this period of adapting to our new reality of distance learning.

I sincerely hope these webinars will continue. I have looked forward to these each week, and they have provided an incredible sense of community and purpose in these difficult times. Thank you to everyone involved for making these happen!

Manisha Sinha did an excellent job presenting the early and continuing history and components of abolition through the voices of abolitionists, both familiar and perhaps those relatively unknown. She also showed the parts some abolitionists played in their work, political and social, after slavery had ended, leading up to and including Reconstruction. Commentary from Adam Sanchez, as well as his sharing suggestions for further reading and other sources, was enlightening and inspirational. Having read some of his extensive writing, it was great to see and hear his views and input, as well.

Presenters

Manisha Sinha is the James L. and Shirley A. Draper Chair in American History at the University of Connecticut and a leading authority on the history of slavery and abolition and the Civil War and Reconstruction. She is the author of The Counterrevolution of Slavery: Politics and Ideology in Antebellum South Carolina and The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition; has appeared on Democracy Now!; and is an advisor for the Zinn Education Project Teach Reconstruction campaign.

Adam Sanchez teaches at Abraham Lincoln High School in Philadelphia. He is a Rethinking Schools editor, a Zinn Education Project teacher leader, and is also editor of Teaching a People’s History of Abolition and the Civil War.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn