On June 26, 2020, the weekly People’s Historians Online session explored the history of rebellions in the United States with a conversation between Jeanne Theoharis and Jesse Hagopian.

On June 26, 2020, the weekly People’s Historians Online session explored the history of rebellions in the United States with a conversation between Jeanne Theoharis and Jesse Hagopian.

As has been the case with the 2020 rebellion, corporate media coverage sheds little light on the roots of rebellions and often casts protesters as violent or destructive. In this mini-class, Theoharis and Hagopian discussed various rebellions in U.S. history. Hagopian noted in his introduction:

When we started this series in late March, our conversations stressed how Rosa Parks worked for decades without ever knowing if there would be tangible results. Her life was a reminder that you may have to hang in for years before a movement erupts. What a difference a couple of months can make. The current rebellion is scoring victories against police in schools and in the fight to defund police departments all over the country.

Here are a few reactions from the participants:

I appreciate Jeanne’s emphasis and encouragement for educators to consider “the many tendrils” that led to this current movement and others before it. And as Jesse mentioned we need to give time and space for our students to share their experiences related to the current moments in the fall.

I really loved the discussion of how a single narrative arose and the way that Black publications actually wrote about uprisings differently.

The “redneckification” of racism challenged my stereotypes of racists and pushes me to confront my biases against the South.

Below, find highlights of the session, a full video recording, recommended resources, and more participant feedback.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: Welcome, everybody. On behalf of the Zinn Education Project, we’re excited to have you back for another session today for our forum on the people’s history of rebellions. Such a needed history to give context to what’s going on right now.

Some of you are joining us for the first time, and some of you have participated in each of our sessions. But for those who don’t know me, I’m Jesse Hagopian. I’m a high school history teacher, I’m an editor with Rethinking Schools, [and I] co-edited the book Teaching for Black Lives. Rethinking Schools coordinates the Zinn Education Project along with Teaching for Change. And I just want to say what an incredible ride this has been. I think we have one more scheduled session on July 10. It’s just been an amazing ride. Investigating a different part of the Black Freedom Struggle has been transformative for me and my understanding. I really want to thank Jeanne so much for taking the initiative on this project, launching this idea, and including me in it.

I just want to say briefly that I think we should reflect on the ark of this forum, because when we started, professor Theoharis and I were talking about Rosa Parks in the first couple sessions, and one of the main lessons that professor Theoharis really was driving home was that we need to be able to struggle in the difficult times, when there isn’t a movement, and that Rosa Parks spent decades working when she didn’t think anything would happen. And then the struggle erupted, just at the point where she thought it wasn’t going to happen. Rosa Parks thought it was going to take forever and she might not see any change in her lifetime, and then [came] the Montgomery Bus Boycott and her pivotal role. To see us in those early sessions hunkered down trying to prepare people for some difficult, low-level of struggle ahead, and now to be in the midst of one of the biggest rebellions in U.S. history, is just breathtaking. I just wanted to take a moment to reflect on that and how people think about where we’ve come in the last months and weeks.

So thanks for joining us, everybody. The Zinn Education Project is hosting this session today, and offers free downloadable people’s history lessons that many of you have used for middle and high school classrooms from the Zinn Education Project website. In particular, we offer a lot of lessons that address the themes of the session today on the roots of the current rebellion. We have lessons on Reconstruction, on the Tulsa Massacre, on redlining, on Reparations, the fight for voting rights, and a whole lot more.

Before I begin my conversation with Jeanne Theoharis, we want to find out who’s in the room and go through our plans for our time together. We are going to do a quick poll to find out how many teachers, librarians, teacher educators, historians, students, labor or community organizers, and educators of all kinds are in the room with us today. You see the poll popped up, so please fill that out. Many of you may be in multiple roles, so then you just pick the primary role. You have an educator, Ciara Kaler-Jones, will post a poll for you all to respond to that you’re seeing here. So throughout the session, we want you to use the chat box to post questions, comments, resources, ideas. Our guest speakers will read your questions and try to respond after the breakout groups. Then we’ll do a short evaluation at the end, so don’t leave before filling out the evaluation. It looks like we have 53% educators; 19% students; nobody identified as primary family members or caregivers; we have 2% librarians; historians 8%; teacher educators 11%; labor and community organizers 3%; and others.

Alright, thanks everybody for being here. I’m happy to introduce Jeanne Theoharis today, who helped vision and launch this series. Jeanne is a distinguished professor at Brooklyn College and the author of The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks and also A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History. I can’t recommend those books enough, especially for educators.

I got in contact with Jeanne first when she wanted support from my Black Student Union here at Garfield in Seattle, to help give advice for converting her book on Rosa Parks into a YA version. And I’m really happy to say that one of the lead students that was part of that project, and giving professor Theoharis that advice, was just awarded the Black Education Matters Student Activist Award yesterday, and it was really beautiful to see how her contributing to that book project really helped give her confidence to become an activist in Seattle, and has contributed to this uprising recently. She wanted to send her thanks to you, Jeanne. So, welcome.

Jeanne Theoharis: It’s so great to be here. Like Jesse was saying, the arc of history, we’re getting to watch it in real time. We had a Rosa Parks moment, I think, a couple of weeks ago, which, I don’t know if people saw it, but longtime abolitionist, Mariame Kaba, got to have an op-ed in the New York Times about abolishing the police and I swear to God, I never thought I would see the day. To me, it felt like, I mean, she’s worked on those issues for so many years, and then to be asked to write that op-ed, and get it published, we’re seeing history in action.

Hagopian: No doubt. It’s really heady times we’re in right now, and I’m so glad to be joining you today for our topic on the history of rebellions in this country. The Washington Post recently ran an article that called the current rebellion we are witnessing, quote, “the broadest in U.S. history,” citing more towns than ever had participated in a single movement. So, I’m wondering if you could just talk about how the size and scale of this, and also the causes and the political character of this uprising, compared to some of the largest in U.S. history?

Theoharis: One of my things that I always write about, and that I think is really important to think about now, is the long road to this moment. That these moments don’t come out of nowhere. That all of the people who have tilled the ground in so many cities, putting these issues out over and over and over. Then, we are certainly seeing a younger generation pick up the baton, which was certainly true in the late 1960s as well, we saw younger generations pick up the baton, whether it was the school walkouts in the late 1960s. To me, this feels a little bit like that moment where you’re seeing really younger kids really leading it.

Certainly COVID, I don’t want to say that it’s one comparison, right, because I think there are very different kinds of landscape. Over the past few months, some people have been doing some needed reflection in terms of the structure of the society and whose work is essential and whose work is valued. So I certainly think that’s also contributing in ways that, again, we can find a sort of direct parallel in the 1960s.

I think one of the things I would ask us to think about are all of the many tendrils that lead to this moment, from what Jesse and many people have been doing in Seattle. We don’t get a free zone in Seattle without years of tilling that ground, which is not to say that there’s not a whole new group of people doing the work now. But I think one of the things that’s really important, and one of the things that was crucially missed in the ways that the 1960s uprisings were understood and covered, was it often was seen as coming out of places that didn’t have political movements. Jesse and I are going to talk about that a little bit later. When we think of the Watts uprising, most of us are not familiar with the long history of movements in LA in the years before that. So, I guess one thing I would ask us to think about this uprising and the ways that we come to see this uprising and all of the work that has kind of gone into making this moment.

Hagopian: Yeah, absolutely. And I’m wondering if Cierra could post the poll that we were hoping to share with everybody about rebellions, wondering if people here have learned about the history of Black rebellions in middle or high school. Did you learn about this history? Did you not learn about it? Have you taught about it? Have you taught your own children about it? Maybe you don’t teach this history yet, but you’re here to learn so you can in the future. I’m really curious how many people have engaged with this history already.

So, it looks like those numbers are coming up on the poll right now. But, I want to dig into some of this history, to give context to what we’re going through today. I mean, I just have to share with you, Jeanne, that one of the happiest moments of my life happened when my son spent a week and a half at planning meetings every night. I mean, he’s an 11 year old kid and he was organizing the Seattle Children’s March, the Youth Shall Lead Seattle Children’s March. And it was incredible. They came up with their own demands — including getting the police out of schools, which I’m happy to report to you we achieved this week. Victory! — they had a demand for a $1 billion college scholarship fund to be paid by all the corporate giants in Seattle, Amazon and Microsoft, etc. And then he went and performed his new hip-hop track, “Police Get Off My Block” at the march. We consciously made that connection to the 1963 Birmingham Children’s March, and it was just so brilliant to see the way understanding history could give people inspiration for moving forward and changing the racist structures today. So that’s what I’m hoping people get out of learning this history today, that they take it into the streets and into the classrooms and make this change.

I’m hoping you can talk more about how white liberals often like to talk about how racism is a southern problem. This was definitely true during Jim Crow, and today, but during Jim Crow, many white northern politicians expressed shock at the explosion of the Black rebellions. You write about this in your book, how shocked they were that these urban rebellions like Watts or Detroit were happening, because there was no racism in our towns, right? As if there hadn’t been a long struggle against segregation and redlining in northern cities. One of the points you make about the uprisings of the 1960s is that people talk about them as if they came out of the blue, and they erase the history of activism in the cities that happened long before these massive urban rebellions. So, I want to ask you about some of the activism that happened before, and I thought maybe we could start with looking at LA, and looking at the antecedents to the Watts Rebellion, looking at Malcolm X and his work around police brutality, and then you write about the campaign against Proposition 14, as well.

Theoharis: On our poll we forgot to ask how many people had ever learned in school about the movement before these uprisings. I would be very surprised to see very many schools teaching these movements, whether it’s in Detroit or LA. So I got interested in this, I was doing a project on the Civil Rights Movement in LA and was surprised to find, because again the received wisdom we got is that certainly there was inequality in LA, but that part of where Watts comes from is this kind of alienated, apolitical, not organized Black community that kind of erupts in the weeks after the passage of the Voting Rights Act. And it just shocks the nation because here we’ve had these milestones and then look, it’s burning itself down. That’s just a very inaccurate way of seeing what actually happens in Watts.

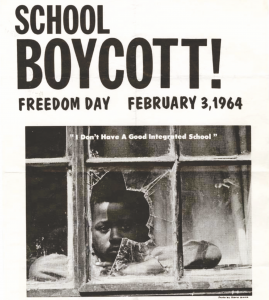

So the first thing, I think, to understand is that places like LA are getting more segregated, particularly around schools, in the decade after Brown, in part because we’re seeing migration, lots of migration, into the West, into the Northeast. This is true in New York City and Detroit, as well. But the school officials are very committed to keeping schools the way they are, so they’re constantly adjusting zoning lines, district lines. So schools are getting more overcrowded, they’re segregated, they’re under-resourced. And then you start to see school districts like LA start to float these plans for double session days — one group of Black kids going to school in the morning and a second group of Black kids going to school in the afternoon, so as not to have to change the lines to bring some of those Black kids into schools with white kids. You see a movement in LA being led by the local NAACP, by the local chapter of CORE, actually by the local chapter of the ACLU, all these groups by 1960, 1961 are organizing around expanding school segregation in the city.

The second thing to remember is northern segregation — and this is true of LA, of New York — part of northern segregation is also the denial of jobs for teachers. So in terms of who’s getting to teach in LA public schools in 1960, it’s also overwhelmingly white, even as the population of LA is not overwhelmingly white. Black and Chicano teachers are having a lot of trouble getting hired. So there’s a whole movement on the ground around school desegregation and teacher hiring. There’s a whole movement on the ground around housing segregation that gets a huge wind, where they finally pushed and pushed and got the state to pass the Fair Housing Act in 1963.

But what we all know about California is they have a much more capacious system for citizens to put [forth] ballot initiatives, and so almost immediately you see this coalition of white and Black associations and realtor groups get together and put on the ballot for 1964, this Proposition 14, which is basically to repeal the Fair Housing Act, which had gotten passed the year before. Again, this is segregation northern style. One of the interesting things we’re going to see in November 1964 is two-thirds of Californians are going to vote to send Lyndon Johnson back to the White House. Civil rights in a broader sense is okay, but there are also two-thirds of California voters who are going to vote for the right to discriminate in the sale and rental of their property. This is the kind of, we could call it hypocrisy, kind of double voiceness of what segregation and racism and antiracism looks like in a place like LA.

The third thing is, we are seeing a burgeoning anti police brutality, anti police violence movement in LA that in many ways expands after 1962. There’s a kind of altercation outside of the Nation of Islam mosque in LA and a number of members of the Nation are hurt. One of the unarmed secretaries of the mosque, a man by the name of Ronald Stokes, is killed. Actually, Nation of Islam members are indicted. They try to frame it as the fault of the Nation of Islam, not of the police. And you see this growing anti police brutality [movement]. The NAACP had already been working on police brutality, had already been going at the LAPD over and over, showing this pattern of police abuse. But you see a much broader, united front movement in LA that’s galvanized after the police killing of Ron Stokes.

Dr. King comes to LA talking about police brutality. He actually comes to LA a couple of weeks after he gets out of jail in Birmingham in 1963, and does this huge rally talking about police brutality. There’s been a longstanding campaign to try to reform the LAPD before what happened in August of 1965. So I think the first way we need to rethink how we teach the uprisings is to lay out these movements in these northern cities that have gotten very little, if anything. And I think we could see a parallel to the uprisings today. We’ve had it for the past many years, a growing Black Lives Matter movement, we’ve had growing local movements around police brutality, with not a lot of progress in terms of really changing the way that policing works. And I think we can see a similar pattern in the 1960s.

Basically, what triggers the Watts uprising is a young man by the name of Marquette Frye, who is arrested for drunk driving. They start to beat him up very close to where he lives, his mom comes out to see what’s happening, and the police start to beat her up. Then a crowd forms and then it turns into a police riot.

I think the other thing to remember, and the other parallel to what we’re seeing today, is that uprisings are moments when the police get a lot of latitude, and when there’s a lot of police violence and where there’s a lot of criminal justice abuses. So you see people being arrested on all sorts of charges that are not going to hold up. Lots and lots of the “looting arrests” in LA in 1965, or in Detroit in 1967, [and] they don’t hold up. Ultimately they are forced to drop the cases because they don’t have any evidence. Similarly, we’re seeing this today in terms of the way these uprisings are being policed, that uprisings are also moments when police do a whole bunch of very troubling things.

Hagopian: I’ve seen it right here in Seattle. I mean, when we had the uprising, at its most fevered pitch, the police just indiscriminately pepper spraying, [including] a seven year old in the streets. Then they were unleashing so much tear gas, the pressure was getting put on our mayor and she actually decided to ban the use of tear gas. Then the police continued to use it anyway. So I see what you mean about that wide latitude given to them. And that rarely gets described as them rioting. So I thought that it was really interesting that you said that, because they’re the ones oftentimes who are completely out of control and causing the most physical harm. Even if some people are destroying some property, they’re causing physical harm.

Theoharis: John Conyers, who’s a Detroit congressman, when the Detroit uprising happened, he literally calls it a police riot. So, in many ways, he’s very clear about what’s happening in Detroit, that the police are doing all sorts of crazy things. So, remembering that history, I think, is important.

Hagopian: For sure. And let’s talk about Detroit, I think that’s fascinating. Also, what you bring about the history before the Detroit Rebellion in 1967 is so important. You wrote, quote, “while both King and Parks are regularly invoked in discussions of racial politics today, their work in the north, and particularly the way they frame the uprisings of the ‘60s, are hardly acknowledged.” You can talk of the same things happening today, right? They’re using Parks and Martin Luther King to try to chastise the rebellion. But maybe you can talk about their work in Detroit?

Theoharis: Again, I’ve just been infuriated by the way that Parks and King have been rolled out. With King, a couple of very interesting things that I’ve recently realized. The first, as I was mentioning, King’s talking about and highlighting police brutality in the early 1960s in the north. One of the things that he’ll talk about after Watts is that there is this real difference in the way that the nation was outraged by what police did in Birmingham in the spring of 1963, but tolerated and allowed what was happening in the north at the same time. And King directly talks about that. One of the other things we see happening over and over is that King is often called to these places like New York City in 1964 — there’s an uprising in Harlem, in New York City in 1964, after the police kill a 15 year old by the name of Jimmy Powell. He’s obviously called to Watts after the Watts uprising. And I think they bring him in as they think he’s going to settle people down.

Then, in both New York in 1964 and LA in 1965, King started saying that what we need [is a] civilian complaint review board [and that] we need an independent body that oversees the police. Then you see these city leaders be like, “get the heck out of here,” right? They don’t want to listen to King because he’s actually talking about how there has to be structural change in the police. In Detroit, similar to what we see in LA, Detroit is both getting more segregated in this period, in terms of schools and in terms of housing, and there is a broad anti-police brutality movement in the city. “Stop Killer Cops” was the way they put it then, kind of growing from the early 1960s. One of the things that’s interesting is that the leader of local NAACP writes that Detroit mainstream newspapers refuse to cover police brutality, they had a standing agreement with the police department not to cover it. I think the contemporary parallel to that is how often stories are written just with the police press release, and not actually getting the other side. So, part of the problem of police brutality in these places is the ways that the media looked the other way and allowed it.

Again, similarly to today, you don’t get police brutality without prosecutors and judges allowing that to happen. One of the interesting things you see post-uprising in Detroit are people like George Crockett, who’s a judge in Detroit who refused to go along with the police tactics during the uprising. He’s elected the year before, in 1966, and there’s all this pressure to just lock all these uprising looters up, and he refuses. He really is very critical of his fellow judges because of their willingness to just allow this kind of policing to run rampant.

Rosa Parks, as most people know, had moved to Detroit in 1957. She’s been in Detroit for about a decade at this point. She’s living about a mile from where the uprising first started, and she’s both upset in some ways by some of the damage, but she’s also very clear that this is about a resistance to change for a long time, that had these movements actually gotten change, and she’s says this and King says it too, that you can’t start the story with the uprising, that you have to start the story with all the ways people tried to raise these issues and all the ways they were ignored or demonized or dismissed. She talks about how the system provokes violence.

Hagopian: Yeah, I wore this shirt for you today.

Theoharis: Look at Jesse’s shirt. Not from December 1, 1955. That mugshot that’s constantly circulated about Rosa Parks. It doesn’t actually have to do with our uprising conversation today, but that mugshot was taken in February 1956. There’s no press there on December 1, 1955. That mugshot is from when a whole 89 boycott organizers got arrested, were indicted — those cities trying to break the back of the boycott — and they all went in together to present themselves, and that’s her mugshot. So, what’s on Jesse’s shirt is from 1956, and it’s for organizing, not for her original bus stand.

Hagopian: Right on. Thank you for that. I just think it’s so important that we get that context to what causes these rebellions. And I think that if we understand, historically, that there was so much organizing against racism before those uprisings, we’ll better understand the moment we’re in today. I think there’s another narrative in the media going on right now about how the current uprising is just mindless criminality. The historic Black rebellions, they’re often demonized in media and in textbooks.

I just wanted to quote to you something that Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor wrote, because I think it’s telling about these rebellions. She said that

the urban rebellions of the 1960s are arguably the most important political events of the decade. And over the course of the ‘60s, public spending on housing and other urban issues went from 600 million at the beginning of the decade, to 3 billion by the decade’s end because of the new federal spending programs, like the Department of Housing.

And she says these are directly tied to the uprising. So she writes, quote,

despite their measurable success in promoting a legislative agenda that helped urban America, the quote unquote “riots” have been largely eulogized as tragic events that cemented a long slide into urban decline and turmoil.

And then she quotes a letter talking about how the hot summer of 1967 and the Detroit Rebellion is the reason why Detroit is a poor city for Black people. So I’m hoping you could talk about what that kind of analysis misses and what was won from the urban rebellions and what role they played in the broader Black Freedom Struggle.

Theoharis: One rebellion that we’re not familiar with actually happened in Birmingham in the spring of 1963. So here’s what we know happens in the spring of 1963. There are these prolonged downtown protests organized by the SCLC, in many ways led by young people, that lead to obviously those horrible pictures of the police tactics, the dogs. That gets both city leaders and downtown business leaders to the table, and they negotiate with SCLC a kind of historic agreement, mostly around public desegregation. And many Birmingham segregationists are very unhappy with this agreement. So a couple days later, they bomb the motel that King is staying at, the Gaston Motel. Then King’s brother’s house [is burned down]; and Black people are at their wit’s end. So, you see that night, this uprising particularly around the Gaston Motel, people come out there throwing rocks, they burn a grocery store down. And I tell you this story because guess what happens after they do this? This is when President John Kennedy comes out in favor of the Birmingham agreement. We often miss that part of what I think gets in there.

Then, similarly, I think part of what Keeanga is talking about, if we look at the uprisings after King’s assassinated, finally we get the passage of the Fair Housing Act, which had been stalled forever. Partly, that’s because of the murdering of Dr. King, but part of that is because people take to the streets. This sense that you can’t just keep putting this stuff off, you can’t not take a side. So, Kennedy sees a kind of urgency, and the ways that people are going to try to capsize the situation that would be bad for him, leads him to speak out on this issue that he hadn’t come out to get on the agreement [yet].

Similarly, with the Fair Housing Act. Certainly Dr. King’s assassination, plus the uprisings, make it so that. . . . I mean, again, this had been delayed for years. We’d been trying to get this for years. It’s like the third, if we’re thinking about the trifecta of the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, and then progress around housing, which northerners hold very dear to their hearts, their rights around their property. But that combination leads to the passage of the Fair Housing Act. Partly I’m also trying to say that uprisings are not just northern, but that somehow we don’t always put them in the story of the south either.

Hagopian: That’s really interesting. I hadn’t actually thought about it that way, so I appreciate you raising the 1963 rebellion in Birmingham. Everything you’re talking about in terms of the victories of fair housing being linked to the rebellions after King was assassinated — like every single city in America went up in flames just about, and people had just reached their breaking point. And the government knew they had to provide programs now.

It’s just so fascinating to me, seeing right now in Minneapolis after the horrific murder of George Floyd, is one of the most intense rebellions that happened in U.S. history, the city council says they’re going to disband the police department altogether and replace it with other forms of public safety. And to me that kind of history is just so important to give a context, so thank you.

We are out of time here and we’re getting ready to move into our sessions for breakout rooms.

[breakout rooms]

If good questions came out of your session, please type them into the chat and we are going to try to answer a few questions that have come up already with our remaining time. Now we’re going to have a chance to answer some of the questions that came up. So Jeanne, one of the questions that was asked was “can you talk about the language used by Northern leaders to undermine or delegitimize the calls for school integration in the 1960s?”

Theoharis: One of the tactics I think we don’t talk about very much is the ways that school discipline and criminalization are on the rise in this period in many big northern districts like LA or New York or wherever. You’re seeing the rise of extreme school discipline, in many ways as a northern response to Brown.

The first tactic is this rise of school discipline and criminalization, in part because northerners want to see themselves as different from southern segregationists. Particularly in the post World War II period, there’s an increasing investment by — and when I’m using the term northerners, I’m talking from the west coast to the northeast, so west coast, midwest, northeast — there’s an investment in not being segregated. But, simultaneously, there’s an investment in keeping their schools the way they are. And they justify it in somewhat different terms. They justify it through this idea, often through a language of either cultural deprivation and crime; that some kids, some families don’t have the right values for success, don’t have the right culture. So you see a flourishing of programs around juvenile delinquency, around cultural remediation, again, in school districts from LA to New York. Sort of a language of cultural deprivation, a language of crime and fears about crime and the need to, in many ways, police these young people. So, there’s all these kinds of apprehensions about these hoodlums.

The second language is a more palatable language they develop, that they’re not opposing desegregation, they’re opposing busing. We have a whole language that fetishizing neighborhood schools and is anti-busing. The first thing I think we want to remember is that most of these places are busing already. There’s busing before “busing.” Or, as Julian Bond would say, “it’s not the bus, it’s us.” But there’s a utility incident in this anti-busing language because, in many ways, the media allows them this space to say “We’re not racist. We’re not against desegregation. We just don’t want to put our kids on a bus for a really long time.” You don’t see reporters push back and be like, “Isn’t your kid already on a bus? Isn’t your kid being bused to a segregated school?”

If we’re talking about Boston, 85% of high school students in Boston are being bused before “busing,” and they’re being bused to segregated schools. They’re being bused because there’s the educational philosophy at the time that you have bigger high schools so you can have a much bigger variety of classes. You don’t see white parents objecting to that until it’s used for desegregation. So [there’s] this culture of poverty, a language around crime, a language around busing, and then there’s all this language around “we don’t know if we have a problem.” So there’s this constant having to prove it, constant commissions, constant studies, and I think we’re in a moment where we have the same potential. Particularly the way I think universities are responding to this moment, there’s all sorts of reading lists, and we’re going to have to think about teaching about white supremacy, and we have to study it and think about it. That’s often a mechanism to not have to act. Like, we have to consider it and figure out what the problem is, we’re constantly figuring out what the problem is, right? All of those things help to shield northern segregation. We want to remember that many places in the north had never seen desegregation, so I think a lot of us educators talk about re-segregation, and that’s true in some places, where there was complete desegregation. But in some places in this country, particularly my own New York City, there was never complete desegregation, so we can’t talk about resegregation.

Hagopian: No doubt. Well, we are getting some good questions here. I want to hit you up with another one from some of our participants here. They asked how might an analysis of class be used to push the current uprising forward? And how can we deal with the psychology of whiteness and white supremacy and historical amnesia that seems to limit the solidarity of poor whites? How would you respond to that question?

Theoharis: FIrst, I think one of the ways that we tend to portray who the racists are is that they’re the poor people. I talk about this in my book as kind of the redneckification of racism, and I think there’s a tendency, and I think we’ve seen this, too, today, we see endless stories about Appalachian white people who supposedly support Donald Trump, right? Statistically, if you actually looked at who supported Donald Trump, the poorest white people actually did not support Donald Trump. Many of them didn’t vote, and many of them voted, but the majority of poor white people did not vote for Donald Trump. But I think there’s been a way, again, if we think about northern investment and being seen as more open and tolerant or liberal than the south but still wanting their schools to be their schools, that what we tend to see is then the fingering of poor white people as the real villains.

I think we can see that in the way that Boston school desegregation, like the image we have is of poor white people in South Boston. And when you actually look at who’s pushing against court ordered desegregation in 1974, it’s happening across the city and it’s happening in many middle class neighborhoods. But what you’ll see is the Boston Globe is often focusing on South Boston and South Boston white people are very angry about that. And they’re justifiably angry, in part, because they’re getting pictured as the face of white resistance when there are many faces of white resistance.

Conversely, I think the other thing we don’t teach are these real moments of multiracial organizing, both then and now. If we think about what Fred Hampton is doing in Chicago, that leads to the Chicago police making the decision to raid where he’s staying and ultimately kill him. Fred Hampton is building this multiracial coalition that includes two poor white groups, Rising Up Angry and the Young Patriots. There are these really interesting moments of solidarity in movements. Obviously, what Dr. King is doing at the end of his life is building a Poor People’s Campaign that is very explicitly about bringing poor white people, poor Native American people, poor Latinos, poor African Americans, poor Asian Americans, and obviously we’re seeing a resurgence of this. Obviously, this past weekend, a huge digital mass meeting, a mobilization by the new Poor People’s Campaign, about showing that poor white people, poor Black people, poor Latinos, and poor Native Americans can be in and build this movement together.

Hagopian: I think that’s so important. Because I was really inspired by the Occupy movement that finally put poverty and inequality in the mainstream lexicon and was able to express the idea that we are the 99% versus the 1%. But I think one of the challenges of that movement was without explicitly taking on racism within our society as well, then actually the 99% aren’t fully united against their common enemy. So what’s amazing about this uprising is seeing how many little towns and poor people of all backgrounds — white poor people, Indigenous poor people, all folks from all kinds of backgrounds — are out in the streets for Black lives.

To me, if you’re able to take on racism forthrightly in your own community, then we could actually build the basis for the 99% to unite around a whole host of issues. Around police brutality, but around all kinds of ways that we’re all stripped of the resources we need — health care and decent education. So I’m hoping the Poor People’s Campaign only gains strength here, and I think it will.

There are a couple more questions I think we can get to here. Let’s see. How should educators address the rebellion of 2020 with students in the fall, and how might your framing of the rebellions of the 1960s help guide our thinking?

Theoharis: One of the main points that I, again, have made in many different ways today is the need to start the story earlier. Whether that’s starting the story before Watts in 1965, or how are you going to tell the story of movements to get us to the 2020 uprising, it’s a similar question to how we need to retell the story. I’d be curious, I would bet in most textbooks that I’ve seen, high school textbooks, the first introduction to the northern freedom struggle is Watts in 1965. You get no movements. I mean, not just not in LA, but not in New York, not in Detroit, not in Chicago, not in Boston. So, part of it is telling that broader history of movements. I think sometimes the like, “Oh, they’re hoodlums,” or, “Oh, they’re asking for these crazy things,” it’s like when you see how year after year people have built movements in these cities around these very issues, and they’re dismissed or they’re promised things that they don’t get. I think that that longer view of how to tell the story, I think is really crucial.

Hagopian: Absolutely. I appreciate that and I hope all the teachers here will go back to try to get that longer view. I had a couple ideas for some pedagogy in the fall. I remember after the Charlottesville white supremacist march and then the counter protests, one thing I did was take photos from that era and put them up around the wall and do a gallery walk and have the students put Post-it notes on the photos expressing how that photo made them feel. We’re going to come back into classrooms with kids who have been through some really intense experiences and are going to need to process them emotionally as well as intellectually. So I think making some space for that.

And then I was thinking it’d be great to interrogate your textbook, right? Get the history textbook out and compare how it talks about Watts. Does it call Watts a riot or does it call it a rebellion? Does it call it an uprising? Does it mention the police riot, like you pointed out in our discussion, leave that out? Then, I think comparing that to different news sources today about the way the 2020 Rebellion is being talked about could be a really powerful way to expose master narratives.

Theoharis: So, how does your textbook explain the causes of the Watts rebellion? It may say the cause is unjust policing. I mean, I think some textbooks probably do that now. But does it say there’s a long movement? Does it talk about Prop 14? One thing I didn’t mention about Prop 14 is the coalition opposing it is a multiracial coalition. You have Japanese Americans, you have Chicanos, you have all of these groups working, so do you get that or does it look like it’s this pitiful community that’s just so downtrodden that then all it can do is burn its community down? I think that’s often how Watts is explained. It’s like there’s these bad things happening and then there’s no political organizing or anything. How does your textbook deal with causes? So, constantly questioning that. Similarly with Boston, right? That’s often the only example of school segregation in the north, but it’s done so horribly. Does it have a 25 year movement before it or does it call the Boston busing crisis? What kind of language is it? Is it a riot or a rebellion? Also, how are they talking about it and who do they describe as segregationists? Are they only people in Mississippi? Does your textbook ever describe somebody in Boston as a segregationist? I would bet $100 no. What language, like are they anti-busing activists? Even that kind of language, how do they explain Boston, where do they start that story?

Hagopian: Yeah, absolutely. It’s going to be an explosive year of teaching in the fall. I’m looking forward to seeing what lesson plans teachers in this session come up with, and I hope people will share those stories with us. We have a couple minutes left. I just want to remind people that before you go, you should fill out an evaluation form. We want to be sure that we get your feedback and we hear what you learned from this session and what you hope to learn more about in the future. We want to leave a little bit of time for you to do that evaluation form now. But before we do the evaluation form, if everybody could just unmute themselves and give a shout out to Jeanne for us. It’s been a great, great run with you, Jeanne. This has been so much fun, the last few months. So thank you very much.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

Here are many of the resources recommended by the presenters and also by participants in the chatbox.

Participant Reflections

Here are some of the responses by participants from the session evaluation.

What was learned

I appreciated the emphasis on framing the 2020 Uprising within a larger historical context, and how to communicate that to our students. Referring it to an uprising or rebellion as opposed to a riot, as well as making sure students realize the hundreds of people throughout history whose work preceded these uprisings. These don’t happen in isolation!

I now want to research more about the children’s activism and figure out how to teach it in my Kindergarten classroom.

To frame rebellions as not just a surprise, but as a response to issues, and to critically think about the framing post-rebellion in the MSM.

There are long periods of organizing and struggle before an uprising, often without much progress. This is important to frame how we got here, but also how to continue forward when the protests are no longer in the headlines.

The way the “redneckification” of racism distracts from acknowledging white, liberal, Northern racism that is equally pernicious and the importance of contextualizing rebellions in the decades and centuries of organized work that preceded them.

Got more context about rebellions from the 1960s and communities I wasn’t as familiar with (Watts).

The names we give historical events reflect white supremacist dominance.

When my kids find out about Claudette Colvin, I think they kind-of write off Rosa Parks and I would like to teach them that real history can include both acknowledging Park’s work but also thinking about why Colvin wasn’t the “right person.” It doesn’t have to be either/or.

The connection of rebellion to the Civil Rights, Voting Right, and Housing Rights Acts of the 1960s — putting the 2020 Rebellion within this context.

Poor people of all races joined in the Civil Rights Movement.

I learned so much about Watts that I didn’t know before. I’m inspired to dig deeper and learn even more. I was already committed to teaching “the long story” but it’s SO important to be mentored and encouraged, so I’m really grateful for today.

I would like to further dialogue with local educators on how they will return to their classroom teaching regarding the Rebellion.

The story of the Boston busing program was an important reminder that I need to revisit. The north, including Canada, is/was not immune.

Inspired to make this topic 2020 Rebellion the focus of my fall curriculum. By framing in relation to Watts, children’s march, Poor People’s, there’s an opportunity to retell the story in the broader history of movements.

Someone in my group made a point about the importance of agency and how we strip that away from BIPOC when we don’t talk about the organizing and causes of a rebellion.

Contextualize the effect that the often not-publicized grassroots work has to teach the whole story, from the pebble tossed into the water that caused the ripple that became a movement.

There were so many gains in things like affordable housing after the rebellions of the 60s. It might mean we may be on the right path with the rebellions currently happening in 2020. There’s also a new Poor People’s campaign happening, so there are lots of patterns happening that in the past, led to positive outcomes. Hoping to see that again. In our breakout room, someone brought up the importance of emphasizing cause and effect in teaching. That seems relevant here.

The emphasis on the type of language used to describe rebellions interested me as my class this next year will be focusing on the use of words, actions, and art to implement change. I think a discussion around words such as riot, uprising, and revolution would be a good way to begin as we talk about current events and begin to tie them to the past.

I think the bit of discussion around rebellion and integration/segregation in schools (especially in the north) is a topic that is really interesting — especially at this moment and thinking both about COVID and the 2020 rebellion’s impact on our schools. The potential for both really important anti-racist work at the same time that COVID leaves us susceptible to really racist practices including more privatization, to white flight, to different levels of access & different exposure to risk of the virus.

I appreciated the reminder from Mr. Hagopian of the importance of giving students space to process these issues emotionally as well as intellectually.

I really loved the question of ‘how will educators teach about the rebellion of 2020?’ — it is crazy to think that we are living through this uprising and, for so many of us, we feel so disconnected bc we are quarantining or staying busy trying to attend to daily life. It is helpful to even have that framing of when we look back knowing the power of the moment we were in.

The format.

Very good session, I thought the questions for the breakout rooms were the best yet. We all grappled with how we were going to frame the rebellion for our students. This was made even more interesting because of the diversity of teachers in our breakout room. From teachers of kindergarten to teachers of teenagers in a variety of different settings from urban to rural, From California to Ireland.

I love the breakout groups because I get a chance to process what I’m thinking and build my knowledge with others. I loved the question in our breakout group because it helped me focus my thinking and focus our discussion.

Great opportunity to hear from educators from all over U.S.

I thought it was really great. Particularly having a facilitator in the break session with as helpful to push people to chime in with their ideas and thoughts.

As always, Dr. Theoharis is such an encyclopedia and I feel like at this point there is such a community feel after all of these weeks.

I really found it all to be incredibly effective and useful.

I think it was short but pretty powerful — I like the idea of maybe having more than one breakout and less talking in between or more consolidated talking points…so we learn juicy nuggets and then go dissect them.

As always, too short. We need to spend a lot of time coming up with new lesson plans for the fall.

The speakers, facilitator questions, conversations are so rich, as are the breakout session, so of course, more time is desired. That said, I am always inspired to continue reading more deeply, grateful for having a more focused eye, and feel driven to continue the work.

The size of breakout sessions is good. It allows everyone time to express their ideas and reflect on what others have to say.

I’ve been enjoying jotting down lists of new historic figures and authors to check out from each of these sessions. All of these topics are bigger than just one session.

Additional Comments

Thank you! I so appreciate these sessions and look forward to sharing what I’ve learned with my students.

Thank you so much to Jeanne & Jesse!

I cannot thank everyone enough for participating

So informative as always! Hope they continue through the school year.

Thank you! I look forward to Friday afternoons.

Thanks for letting students be a part of this!!

Thank you so much, it is wonderful to be a part of these. Thank you so much for all the love and passion you pour into these. It means so much to me. Please don’t stop!!

This was a great opportunity to see people’s different perspectives on the movements both in the 1960s and now in 2020.

Thank you! The solidarity and community found in this session give me hope. You all challenge me to do better.

This was my first session and I really appreciated the conversational approach. There were so many wonderful resources being shared!

I deeply appreciate this 75 minutes every Friday. It gives me time for reflection, rejuvenation, and recognition that we are not alone. Moves me to organise for international solidarity.

As another participant said, “these sessions are nourishing.”

Presenters

Jeanne Theoharis is a distinguished professor at Brooklyn College. She is the author or co-author of nine books and numerous articles on the Civil Rights and Black Power movements and the politics of race and education. Her books include the award-winning titles The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks and A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, and editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn