Hearing from people who were directly involved in the Civil Rights Movement is always so impactful. It is also a reminder that these struggles did not occur in the very distant past but within the lifetimes of folks who are still very much active and involved today.

Courtland Cox, Judy Richardson, and host Jessica Rucker lifted my soul with inspiration. Thank you all, I really needed that.

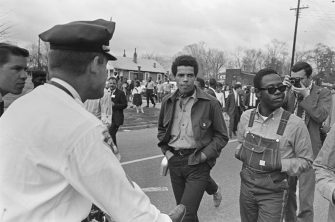

The energy in the “room” during the April 24 People’s Historians Online — even at a distance — was palpable. Close to 200 teachers, parents, students, and others gathered via Zoom to learn about the history of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) on this 60th anniversary year. SNCC veterans Courtland Cox and Judy Richardson were the featured guests, in conversation with high school teacher Jessica Rucker.

Here are some highlights of the session. Further below we offer a full video recording.

After describing the origins of SNCC, Courtland Cox talked about the use of “comic books” for popular education as they organized for voting rights in Alabama in 1965. These are described on the SNCC Digital Gateway website:

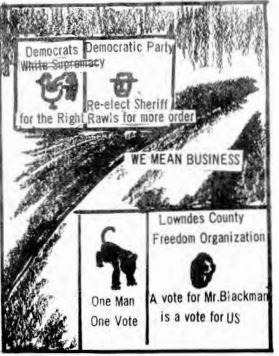

One often overlooked aspect of SNCC’s organizing is the creativity invested in political and economic education. Lowndes County, Alabama was a clear example of this. There, in 1965, SNCC organizers designed and distributed comic books to educate people about local elected officials, so they could take charge of their communities. In the comics, SNCC “got people to believe” in their power to affect change by building a base of political power. “Us Colored People,” written by Courtland Cox and illustrated by Jennifer Lawson, showed how a character named “Mr Black Man” became politically awakened, registered to vote, and ultimately county sheriff himself. The comic book explained the political strategy: “The way to deal with [police brutality] is get a new sheriff, who accedes to your view of the world.”

One often overlooked aspect of SNCC’s organizing is the creativity invested in political and economic education. Lowndes County, Alabama was a clear example of this. There, in 1965, SNCC organizers designed and distributed comic books to educate people about local elected officials, so they could take charge of their communities. In the comics, SNCC “got people to believe” in their power to affect change by building a base of political power. “Us Colored People,” written by Courtland Cox and illustrated by Jennifer Lawson, showed how a character named “Mr Black Man” became politically awakened, registered to vote, and ultimately county sheriff himself. The comic book explained the political strategy: “The way to deal with [police brutality] is get a new sheriff, who accedes to your view of the world.”

Teachers commented (in the chat box) that they could use these in their classrooms to teach about the history of the Civil Rights Movement and to help students think about strategies for organizing today.

Courtland also shared the origins of the black panther symbol (a precursor to its use by the Black Panther Party in Oakland) as a counter to the rooster, the symbol of the white supremacist Democratic Party. (Read more in Lowndes County and the Voting Rights Act by Hasan Kwame Jeffries.) He emphasized that their work was not just to get the right to vote, but for “regime change.”

Judy Richardson emphasized the power of music. She shared stories about Bernice Johnson Reagon (who later founded Sweet Honey in the Rock). Reagon is quoted at the SNCC Digital Gateway,

More than anything, freedom music was a tool for liberation–“an instrument,” Bernice Johnson explained, “that was powerful enough to take people away from their conscious selves to a place where the physical and intellectual being worked in harmony with the spirit.”

In her closing, Judy said a line that got repeated often in the chat box, “If you do nothing, nothing changes.”

Facilitator Jessica Rucker shared that she brings this history to her students with the SNCC Digital Gateway website and a lesson at the Zinn Education Project website, Teaching SNCC: The Organization at the Heart of the Civil Rights Movement.

Here is a video of the full session (except the breakout groups.)

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jessica Rucker: I’m Jessica Rucker, a high school teacher based in Washington D.C. I am so very happy to be in conversation today with SNCC veterans Courtland Cox and Judy Richardson. Before these two SNCC veterans jump in, I want to note that Courtland Cox is the chair of the SNCC Legacy Project board and Judy Richardson is also a member. Courtland, I am going to start this conversation with you. For people who are learning about SNCC for the first time, please tell us who and what SNCC is and how and why SNCC got started.

Courtland Cox: Thank you. First of all, I’d like to thank the Zinn Education Project for hosting this virtual meeting. I want to give a shout out to all the teachers, parents, and students in the audience. I put myself down as a historian, but I don’t actually teach history. But, what I’m going to try to do today is give you my sense of my life from the inside out. So, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee — and I’ve made some notes to refer to — was founded at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina in April 1960. The meeting at Shaw was called by Miss Ella Baker to provide some coordination and structure to the numerous citizens that spread rapidly across the country after the February 1, 1960 sit-ins started in Greensboro, North Carolina.

The sit-ins were mostly conducted by students from Negro colleges. We don’t refer to them as Negro colleges anymore; they’re known as HBCUs. At the SNCC meeting, there were about 126 representatives from 40 Negro colleges and Black high schools. While it may not have been obvious to the students who attended this early SNCC meeting, the SNCC convening at Shaw was the culmination of a series of actions that were taken by civil rights organizers over a twenty year period. Upon reflection, I really consider the founding of SNCC a new phase of a struggle that had been ongoing.

While it’s difficult for many of you, looking at my gray hair and bald head, to understand or to realize it, in 1960, most members of SNCC were between the ages of 17 and 22. For most of the secondary school teachers in the audience, many if not most of the early SNCC members were of the age of your students from last year and the year before. I graduated from high school in the spring of 1959. I arrived as a freshman at Howard University in January 1960. I worked in the post office from June 1959 to January 1960. And you could do that at that point because at Howard University tuition was $110 a semester, room was $40 a month, and food was $40 a month. I also need to say that my salary was $2.20 an hour.

As I think about it now, I was drawn to supporting the sit-in movement in the south and participating in the SNCC sit-in movement in Washington D.C. because over a six year period, starting at the age of 13, I was influenced by several discussions, arguments, and stories that are either occupied or either occurred on the sidewalk on the baseball field in the Bronx, New York and Throggs Neck projects where I lived in 1954. I was 13 years old. The sidewalk discussion was about Brown v. the Board of Education. The adults in the project celebrated the Supreme Court decision, but they celebrated it because Kenneth Clark was involved in the research and in the conversations that I heard about Brown v. Board of Education nobody talks about Thurgood Marshall, nobody talks about the NAACP. It was all about Kenneth Clark because he was a native New Yorker.

In 1955, when I was 14 years old, two major historical events occurred. The first was the murder of Emmett Till in August of 1955. The second was the beginning of the Montgomery Bus Boycott in December of 1955. As you know, the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott was led by Martin Luther King Jr., a 26 year old preacher. He popularized in America the use of the nonviolent teachings of Mahatma Gandhi that were developed in South Africa during the turn of the century, and perfected as M. K. Gandhi tried to bring an end to colonialism in India. His nonviolent teachings became very, very important as the central operating principle for all of the Civil Rights Movements, including SNCC in 1957.

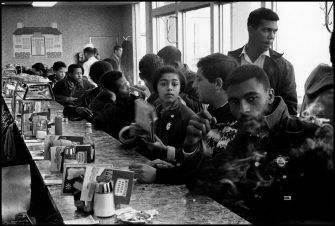

When I was 16 years old, I witnessed on my 19” black and white TV — and there were only three major channels at the time — the attempts of nine Black students to integrate the Little Rock High School in Arkansas. The federal government, for the first time, had to enforce the laws of the land that were established under Brown v. Board of Education. Therefore, in 1960, many of the students at the Negro colleges, who saw on their black and white televisions the ongoing challenges to both these de jure and de facto segregation, were more than ready to end racial barriers to their lives. So, within days of the February 1 sit-ins, other citizens spread across the country like wildfire, and 75 days later the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was established to provide better organization and support.

Rucker: Wow. Thank you for that rich social history. I love what someone in the chat box described as the “genealogy of SNCC.” One of the points you made, Cortland, was about nonviolent direct action. So, my next question is for Judy. I love the role of art and music as a direct action strategy, or elevating direct action strategies. Every movement needs a soundtrack and SNCC really harnessed the power of freedom songs. Please tell us why freedom songs were so important to the movement.

Judy Richardson: I love talking about the music because the freedom songs served a number of purposes. They were really part of the major glue that held us together. They were songs that made you feel unified, that you could do anything, that no matter what the cops were doing, no matter what these white supremacists were doing, you were together and you were united in song and your voices. But the main thing was when you lifted your voices in song with all these other people, like you’d be coming out of jail and you’d come into a mass meeting in the church and people would be singing, and it was like nobody could touch you.

There was also a sense of resistance. There’s a story that Bernice Johnson Reagon often told — and Bernice, as many of you know, was the founder of Sweet Honey in the Rock, but before that she’s a song leader out of Albany, Georgia, in southwest Georgia — she’s a SNCC staff member, and she’s doing the Freedom Singers for SNCC, but she’s also organizing within southwest Georgia. She talked about how, in this world church in Dougherty County in southwest Georgia, there was a mass meeting, a small [meeting] because [they were] always small at the beginning, and she said, “They’re talking about the business of the movement, and who’s gotten arrested, who’s gotten beaten in jail, what money may be possibly collected from people to keep the movement going.” And then suddenly, in the middle of this meeting, the sheriff comes in — white, of course — and he has guns on either side of him. He walks in and he gets to the front of the mass meeting in the small rural Black church and he starts calling them by name. He says, “John, does Mr. Thomas know you’re here? And Betty, does Miss Johnson know you’re here?” to let the Black people in that church know that the white supremacist sheriff knows who you are. “I’m going to go back and tell your employers.”

Since everybody was living really on the edge, near starvation, in these rural areas, what that meant was, I’m going lose my job and I’m gonna lose my livelihood, and it’s possible that they are going to try to shoot me. So, this sheriff is going by and he’s saying everybody’s name. and then suddenly somebody at the back of the room starts singing, “Oh, I ain’t gonna let nobody turn me around,” and suddenly this one voice becomes three voices and this whole group at the small mass meeting is singing not just for themselves, but singing at the sheriff. Because it’s a song of resistance. singing at the sheriff. I know that you can have the power of life and death over me, but that’s not going to stop me anymore. There is a sense of strength that you got from this music.

What Bernice often said was when you looked at the sheriff and he heard the song, she said, “You could tell by the look on his face that he suddenly realized that the Black people in front of him had changed. They were no longer the scared Black folks that he had been accustomed to being, because he didn’t know that some of them might have been in the NCAA already. “He didn’t know any of that. What he didn’t know is that these folks visibly had changed because of the power of the song.

Now we also use it internally within SNCC. I remember when,, I think it was around 1964, when we come back from Atlantic City, and the liberals, who we thought were going to support us, they didn’t support us because of Lyndon Johnson and a variety of things. But, we came back and I realized we’re trying to figure out what to do now. Sometimes when you don’t know what you’re doing within a movement you start internally attacking each other. It becomes fratricide. So, we were in the middle of this meeting and people were arguing, and they’re arguing in a way that I’m not sure the organization will survive. Suddenly Jim Forman, our executive secretary — who, by the way, also couldn’t sing that great — he suddenly started singing “Will the Circle Be Unbroken?” He’s singing this and I’m thinking these folks aren’t going to sing like they used to, we’re beyond that, people are too mad at each other. They’re just going to let him sing by himself and be quiet. And suddenly Jean Smith starts singing, so and so start singing, they start singing, and what it did is it reminded us who we were, what we had meant one to the other. All the history that we had been through together. Suddenly, all the staff meeting are singing “Will the Circle Be Unbroken?” and it reminded us of what we had always talked about, which was that we were a band of brothers and sisters in a circle of trust. That’s why, 60 years later, we’re still doing what we’re doing. It’s because of that unity. But the song was so important to that.

Rucker: Goodness gracious, again, thank you so, so much. Now I want to transition a little bit. The song is such an incredible bridge. Tell us about SNCC moving the national office to Greenwood, Mississippi, and the people that you encountered who were already organizing in Greenwood. And I’m really interested in June Johnson and the incident with Silas McGhee.

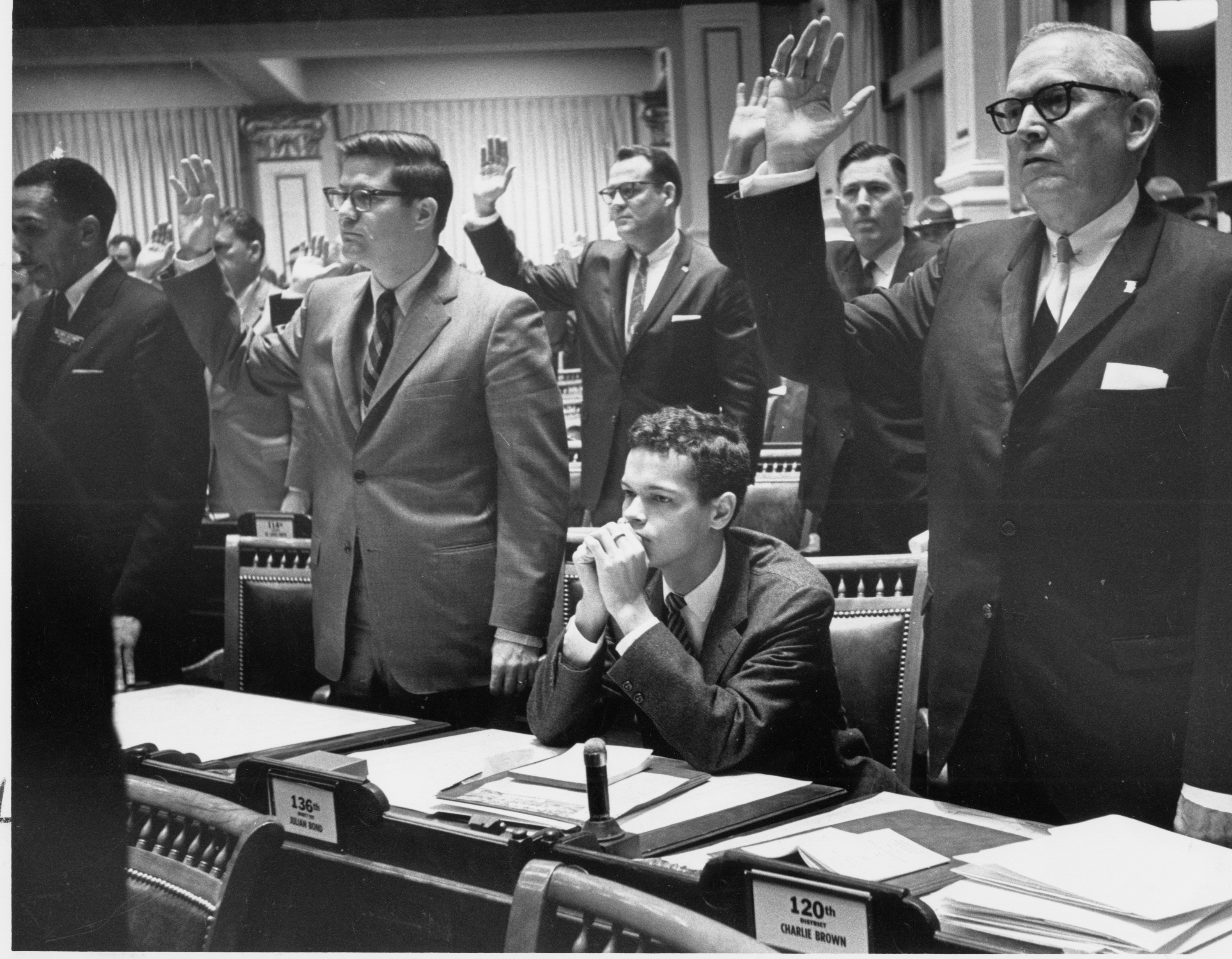

Richardson: Yes, indeed. Well, SNCC decided to move a portion of the national office, which had been in Atlanta, to Greenwood, Mississippi. For example, Betty Garman Robinson, then Betty Garmin, comes down with the Friends of SNCC. And Julian Bond comes down, who was head of communications. John Lewis is traveling around. Stokely [Carmichael] is already there. Cortland is already there. We have all these people. So part of the office moves down to Greenwood. When Bob Moses, who was our main person and the main leader within the Mississippi Freedom Movement for SNCC, went into Mississippi in 1961, and then really went back in in 1962, he’s really guided by Amzie Moore. I’ll tell you about that at some other point.

Bob says when he goes in 1962, Amzie, who at that point is in Cleveland, Mississippi, lays out a precinct map on his kitchen table and says, “Look, you young people can do sit-ins if you want to. But, I know that our power as Black people will be around the right to vote.” Now, Amzie knew this because he had been part of this Regional Council of Negro Leadership, these returning Black World War II vets like Medgar Evers, like Amzie Moore, they had formed around economic justice, around voting rights, around a lot of different issues in 1950. In 1951, they had a meeting of 15,000 Black folks in Mound Bayou, Mississippi. I couldn’t believe it, but that’s another story. So, Bob is sitting there with Amzie, who, as most of the local people were doing for us, is guiding and guarding us with their guns. Amzie puts out this precinct map and says, “Look, this is where the concentration of Black people are. This is where we’ve been working all this time.” And he said, “But I’m not ready for you here yet. I don’t have the organization here in Cleveland yet. But C. C. Bryant has it for you down in southwest Mississippi,” which is why the first real Voting Rights Project happened down in southwest Mississippi.

But when I go there, it’s 1964, so what I’m coming into is something that has been going on for some time. For example, there are the Greens, and George Green who became a SNCC staff member. Their family was a strong family. June Johnson’s family was a strong family in Greenwood. By the way, Stokely used to stay with Freddie and George’s family. So, when I get down there, intellectually you can know that people want to shoot you, you know that, but to actually be in a position where they really try and do that . . . I mean, I’m coming from Tarrytown, New York. So, what happens is that I’m sitting there in 1964, it’s Freedom Summer, those three particular civil rights workers that were missing, we knew they were dead. Cheney, Goodman and Schwerner. But their bodies had not yet been found.

So, at some point, June Johnson, the strong 15 year old from Greenwood, Mississippi, went to the SNCC office. I had the keys to one of the SNCC cars — we had this auto fleet called the Sojourner Auto Fleet, so I had one of the keys — and she says, “We’ve got to go down to the hospital because the McGhee brothers had just earlier that day tried to integrate.” They had tried to integrate a movie theater and when Silas comes out, one of the brothers, he sits in the car and some white racist throws a rock through the window and glass gets in his eyes. He is now at the segregated hospital in Greenwood, so June comes — again, a strong family, she had been working since long before I got to Greenwood — and she says “We’ve got to go because they’re at the hospital.” So we get in the car, June, me, and two other people, and I’m driving. At some point this car comes on the side of us with a white couple, and they start motioning and doing things and they indicate that they are not our friends. So June says to me, “Speed up.” Now, in my mind you don’t go over the 25 mile per hour speed limit because then they will arrest you for speeding. Then we hear sounds and Jean Smith says, “Hurry up, they’re shooting at us!” And I said, “Oh no, no, June, that’s just a backfire.” Now June is from Greenwood; you would think I would listen to her.

We get there and it’s the Greenwood hospital. There’s this small white mob with some bricks, bats, and stuff we went from the car into the Greenwood hospital. I see six FBI men and they are walking around the reception area, so I run and June immediately goes in the back to find out how Silas is doing. I see these six — all white, of course — FBI men, and then somebody throws something through the window, this picture window in the hospital reception area. We all went behind this wall, including the FBI man, and then that’s when they got seated all six of them. I started thinking this is like the monkeys — see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil. And I started screaming. I knew that the FBI did nothing; all they ever did was to take notes. They could see horrible infringement of federal law, but they would do nothing. So I started screaming like a crazy person. “Why don’t you do something?” By the way, there really is an advantage to righteous anger. It’s not all nonviolence; I was pissed.

Then I had my little dimes because nobody had cell phones. I peeked around, and June Johnson still remembers that. She said, “Yes, you peeked around and you went to the little payphone in the reception area.” I started putting dimes in to call John Doerr, who was the most wonderful person in the Justice Department, in the administration, and I kept calling him. Then, finally, because of the calling, and because I was talking to Forman and I was talking to everybody through these little dimes. I should mention the FBI guys never came out from behind the barricade. Eventually, because of the pressure and because we’re calling the Friends of SNCC, and this and that student campus’s Friends of SNCC, our network already existed, and because of that, there’s pressure being put on the local sheriff, because our offices have given the number of the sheriff. The white sheriff comes and escorts us out. So, for me it was, first of all, you need to listen to the local people, because they actually know what they’re talking about. Don’t think you know what you’re doing. But, it was also the sense that we had a network that was looking at us, that was helping us, in addition to the local movement that was there.

Rucker: Thank you, again. As I’m listening to you share these stories and thinking about my role as a teacher and as an African American woman here in D.C., what keeps coming up for me over and over is the ways in which you are humanizing this movement. You are a real person, these were real people, these are real issues, and these are real changes. I think the more I can translate that for students, the more this history sticks. So, I have a million follow up questions.

But I want to switch gears and I want to kick it back to Courtland, because I wanted to pick up where SNCC is doing grassroots work with local people, honoring the voices of people who’d already been doing base-building work. This is the 150th anniversary of the 15th Amendment, and also an election year, importantly. Tell us how and why SNCC focused on voting rights in Lowndes County, Alabama. Then, I’m also interested in who were some of the local people you all worked with while organizing there. Let’s start there.

Cox: Judy mentioned that the sheriff came into the mass meeting and thought that he had license to exercise power in Mississippi. We have to remember that Lowndes County came after Mississippi. By the time we got to Lowndes County in Alabama we had a very different attitude about how we began to look at the issue of power. Lowndes County was 80% African American, but there were no Black registered voters in Lowndes County. We decided that it’s one thing to go about talking about registering to vote, but the real issue, given Judy’s example, is about power.

There are three questions around that. Who should have it? Who should exercise it? And who should benefit from it? Those are the three questions that we had. But the issue was a problem. You now have a population of 80% African Americans but they’re being treated and brutalized by the political establishment. I mean, as opposed to going to protest — as we usually did in the past, and calling people — we decided it’s now time to exercise power. But, the trick was how do you [convince] people who never voted to believe that they not only could vote, but could run a county, be the sheriff, be the tax collector, be the probate judge, and so forth? So, Jennifer Lawson, Judy, Stokely, Willie Ricks, and Ralph Featherstone got together and went in there. Fortunately, we had Jack Minnis, who was a genius in terms of research, and he found out how we could probably answer this question.

The state of Alabama had a law that said that you could establish a political party, just on the county level. So we said, “Okay, we have 80% of the vote, we need to have 80% of the power. How do we go about this?” The first thing we decided to do was educate the population. We couldn’t have great tracks to educate people, so what we did was we developed comic books. We had several comic books; one comic books had a picture of Mr. Logan and [talked about] the responsibilities of the sheriff. The other is the Board of Education. What were the responsibilities of the Board of Education? We had a picture of everybody who was running for office on there so that people could see the person who they were supporting. Because we had two big problems: We had to educate people about what the responsibilities were, but probably the bigger problem was to get them to believe that they could do it themselves. Given all the things that they had suffered all through these years, they had to believe in themselves that they could do it.

So we did two kinds of comics, one that had the statistics and facts, and the other was one we called Us Colored People. We developed that, Jennifer Lawson and myself, because again, in Mississippi listening to the people, a woman in a mass meeting in Mississippi got up and she said, “Us colored people have been using our mouths to do two things: to eat and say “Yes, sir.” It’s time we said no.” So we took that whole story and we created a comic book.

The next problem that we had and tried to solve was that a lot of people could not read and the literacy rate was pretty high in Lowndes County. How would you get people to vote correctly? How do you get them to vote for the right person? So we decided to do what was done in a lot of places already — get a symbol. The Democrats in Alabama already had a symbol, which was a rooster. It said “For the right” on the top of the rooster and on the bottom “white supremacy.” So, we decided we were going to get a symbol and that symbol was the black panther. I mean, we actually were trying to find a mascot and we asked people in Atlanta, and Ruth Howard, I think it’s the symbol of Morris Brown in Atlanta. My sense is we liked the black panther because it showed strength and it was big and people could identify with it. At the end of the day what we were able to do was get people with their individual votes to act in a mass fashion. We created the tagline, I guess it’s called a tagline, “Now vote for the Black Panther and then go home” so that people were able, as individuals, to act in such a direction that they were able to exercise power.

Now, when I look at it, I think the Lowndes County experience and this whole exercise of power had reverberations way beyond what happened in Lowndes County. We can talk later about its importance to the call for Black Power by Stokely and the formation of the Black Panther Party in California. But, at the end of the day, when we look at Lowndes County, if you were going to sum it up, we were intent on regime change. We were going to make sure that the sheriff who dealt with the people in Lowndes County didn’t have to ask him to be nice because the sheriff was going to be somebody from that community who understood the needs of that community.

Rucker: This is so powerful. I just want to recap a couple of things. As a teacher, again, I’m wearing my teacher hat. I’m thinking about the consciousness raising that you all were doing, and also competence building through using popular education strategies. As a teacher, differentiation is so important. I’ve got to start where students are and honor the knowledge that they bring in the classrooms. The political education and then the use of the Black Panther, using culturally relevant content to ground my teaching is so important. Then, also, base-building through the use of slogans. When I offer students bite sized processes to engage in the learning we can go deeper and deeper, and it’s so powerful to see the parallels between the community organizing work of SNCC and the work I get to do as a classroom teacher in D.C.

[breakout rooms]

Judy, I want to start with you. Some teachers, students, activists, and organizers feel that we are working in conditions that seem impossible. Can you tell us about the production of the 14 hour documentary series Eyes on the Prize? How did it differ from previous documentaries and what did it teach you about creating something that had not existed before?

Richardson: Perfect question. When I first started it was 1979. We’re Blacks on the Black side in Boston, Black owned film company that had never done anything for broadcast, headed by Henry Hampton. He brought me up as the first staff person in 1979, and at that point we think we’re doing a one hour documentary. I’m sitting there by myself looking through research and I’m looking for Stride Toward Freedom, Dr. King’s account of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, and I find the name of Jo Ann Robinson, head of the Women’s Political Council. I’m so amazed that I’m finally finding the name of a woman, because most of the documents did not mention women. So I try to find her and that’s a whole other thing, too.

One of the first Black journalists at the New York Times, Jarrell Frazier, because I’m trying to figure out how to find her, he says, “Well, sometimes people are listed in the phonebook.” So, I finally got her through the phonebook in LA, and she was so excited to tell me the story because no one has asked her about it. She talks about how she’s co-chair of the Women’s Political Council with Mrs. Mary Fair Banks and edited all that we now know. But back then in 1979, nobody knew about her except for the people of the boycott. What was amazing to me is that, having come from what we all knew was a regular people’s movement, it was your aunts and your uncles and your clergy sometimes, whoever was in your community, they were the ones who were part of this movement. And that was not in anything that I was seeing in 1979.

The only film at that point was Montgomery to Memphis, which is Dr. King 24/7. Even when he goes into Birmingham you don’t see Reverend Shuttlesworth, you only see Dr. King. Wherever he goes, the focus is only Dr. King, not the strong local leadership that might have been there before he gets there. Like in Selma with Mr. And Mrs. Boynton. I’m not seeing anything that reflects the experience, that on the ground experience that I’ve come out of from being in SNCC. The danger is that if you don’t know that it’s people just like you and your families and all these other people around you, they were the ones who made and continue the movement. If you don’t know it’s people just like you who did this then you don’t know you can do it again. And then all those other crazy people, they win. So what it does, it breaks with what is out there already when we come on with the first six hours in 1987.

At that point, we didn’t have Charles Payne’s wonderful book, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom. We didn’t have John Dittmer’s [book on the] Mississippi Movement and the origins of organizing. We didn’t have any local movement history at that point. So, what it does is it opens it up, it shows that it’s people just like you who made and sustain the movement. You see Amzie Moore and you see E. D. Nixon, you see all of these regular people, and you see women in leadership, and you see young people in leadership. It’s the first time that you have seen this in anything at that point. That’s 1987 with the first six hours.

The other thing you get is a sense of how long things take. Now, because films are films, you don’t get enough of a sense of that. But, certainly one of the things that we tried and say even in Montgomery is how long have they been marching? Now it’s three months, now six months, and that’s the point. Sometimes I’ll be in a room, like a mass meeting, and I’ll have people come to me, young people now, who will say, “What are we doing wrong? You had mass meetings of 300 people overnight.” Well, the point is, and you see that in Montgomery — 381 days they were walking; they didn’t take public transport for 381 days. They stay together for that amount of time. So, for us, mass meetings could be you, your co-organizer, and her mother. That was the mass meeting. And it could be that way for six months, could be a year; you never knew whether something was going to break out. That’s important for young organizers today, because sometimes they think they’re doing something wrong because they have a sense that all this happened overnight.

The other part is you never knew whether it was going to work. Nobody knew Montgomery was going to really work and they were going to be able to break the back of the bus system. You don’t know. I think what it does is it talks about regular people, it talks about all the folks who were in leadership, and it talks about how long and how big that opposition is. It’s not only in the white community, because sometimes it’s coming from the churches, it’s coming from the Black businesses, it’s coming from a lot of different areas. What it does is it gives you a sense of what that initial struggle was. Then the next eight hours are really about the continuing movement.

Rucker: Wow. Thank you. Some of what I’m gathering is that there’s no spontaneous combustion, that’s one of those movement myths, and there are no superheroes. One point that I want to carry over from a previous session is that young people carry a lot of power. But some of the choices that youth were making were not always considered popular at the time. Some of the feedback that some of my students get when they want to organize and take direct action, it’s like, “Y’all are too loud, too raucous, and you don’t know what you’re doing.” I think there’s some historical amnesia that comes with the long history. Ordinary people are capable of extraordinary things but are often met with complex opposition. The resistance has to be just as strategic and as savvy and as patient, as well.

I want to kick over to a question for Mr. Cox. So, 2020 marks the 60th anniversary of the founding of SNCC, and this month SNCC was scheduled to host a historic 60th anniversary convening with movement veterans, current activists and organizers, teachers, students and other justice oriented folks. Can you tell us how you are moving the convening online and what the plans are for 2021?

Cox: Let’s start with the beginning. The SNCC 60th convening will be held June 3–5, 2021. You can put it on your calendars, COVID-19 permitting. I think one of the things that I’ve learned, it’s very hard to understand: for most SNCC people, they never really see themselves the way people see them. The way you look from the inside out, you’re just living your life. From the outside in, you’re creating history. My sense is we’re getting a lot of people saying we were coming to this convening of the 1960s, not because it was something to do, but because we had vested interests in understanding what you were trying to do. As somebody said, there was a certain authenticity to what you did and what you are doing over the years.

Now, talking about young people, one of the things that we have learned, and I learned early on, it’s really, really hard for young people to understand, because we felt, and every young person feels, that if I put my energy, and if I put my time, and if I really want it to happen, it will happen. Given the things that we’re dealing with, you find out that everything that you did was necessary but it will not be sufficient. We have been out here for 60 years, and we have done things and we’ve continued to do things for 60 years. We have done everything that we could accomplish, but we know we have much more to do. So, I think one of the things, besides understanding that change is not made by a majority, it’s made by the minority, the other thing we have to understand is that big things have changed since Judy and I got out there. I mean, we don’t have to deal with the kinds of things that Judy mentioned, like the sheriff. Well, if a sheriff walked into a meeting of Black people and started talking like that sheriff talked and the Black people started laughing at him, they wouldn’t be scared of him. That has changed.

But we look and see what has happened in Congress today, where people who have power control trillions of dollars and it goes to themselves and not the people on the frontlines. The workers and the people who are facing COVID day after day get little resources and have to fight for resources. In the $2.2 trillion [budget], you have $170 billion going to real estate developers and going to people who are hedge fund managers, while people on the frontlines can’t get masks. So, my sense is the struggle continues in a different form. Everybody has to understand a number of things first. One, the minority makes the difference because they have a view of where they’re going. Two, as you try to do it, it doesn’t matter how much you wish, it doesn’t matter what you think, and while everything that you do is necessary, a lot of it will not be sufficient. You have to continue over the years. It is going to be an ongoing struggle so you should not get frustrated. As King used to say all the time, the arc of the universe is long, but at least we think it bends towards justice.

Rucker: Thank you. We had a question about teaching power. As teachers, what would you want teachers to teach about power based on your lived experiences? If you could give us the microwave version and not the conventional oven [version], because we’ve got a couple other questions, too.

Cox: Judy mentioned Bob Moses. It seems to me that the nice thing about power is that the kids understand that they have it themselves, as they’re the ones who are the best educators. Not only that, they are the ones who challenge each other to get better. I mean, the best thing a teacher can do about power is show the student that they have it within themselves to exercise.

Richardson: I would just add to that, because that’s perfect, that as much as you can, show visual stuff. That’s just because I come out of visual stuff. It helps. I mean, one of my favorite films is Freedom Song with Danny Glover and Loretta Devine. It’s about what happens when SNCC moves into southwest Mississippi. It’s a wonderful, wonderful movie, and you see young people taking the power. You see it, it’s not just somebody telling you about it.

Rucker: Another question, and this one’s for you, Judy. Would you be able to share your perspective on the SNCC position paper on women in the movement?

Richardson: I mean, I remember it happened. We were at Waveland, and it was right after 1964 in Atlantic City. I will say, and I possibly was unusual with this, the person I was going with, Ivanhoe Donaldson, showed it to me, gave it to me. He said very seriously, I mean, he was in no way dismissing it, he said, “What do you think of this?” I read it and it didn’t seem to apply to me because, at that point, my main thing was racism. I mean, we were getting killed not because we were women, but because we were Black. Some of that changed, but at that point it was “we’ve got to stay together.”

I think for a lot of the Black women in the organization, they didn’t quite see it in the same way that some of the new white female staff members might have seen it. Although not all of them were. Mary King certainly was there before I got there, and Casey Hayden had been there before I got there, both white women. I think the reaction to it was a little different based on the race of the woman who was looking at it. I will say, sexism is real. There were things that I had to fight against. But most of that comes after I leave the organization. You will hear it in Hands on the Freedom Plow, most of the Black women who are in that anthology, the 52 Black women, will talk about how they felt the most powerful as they have felt in their lives, when they were in SNCC and support. It didn’t mean there was no sexism, it just meant it was so less. Because we were young people, we just thought the guys were different. I mean, they had Miss Baker, it was Diane Nash, it was all these women who were leaders of certain movements, schools, who were part of the leadership of SNCC. So, not that there was no sexism, just that it was different.

Rucker: This has been a very rich conversation. I want to ask Courtland and Judy if you have any closing remarks that you want to make, or if there’s anything else participants should know about SNCC from your perspective?

Cox: I want to thank the Zinn Education Project because it seems to me they are very valuable. At this point in our lives. Judy and I are the wholesale people, we have wonderful stuff, but you are the retail, you bring it to the students, you are the ones who make what we do real and make it alive. So, I think the support for what you’re doing, and particularly the framing and getting teachers together, is particularly important. As I said, the sense of knowledge, the sense of understanding, the sense of clarity is going to make the difference for the next generations. One of the things that we’re doing is. As Miss Baker said, we are emphasizing the continuing discussion, we’re continuing the multigenerational discussion, and the Zinn Education Project is key to that discussion.

Richardson: I would just say two things. One, is that SNCC people donate to the Zinn Ed Project. I mean, that’s the thing. One of SNCC Legacy Project board members put up a challenge to get the new book, Teaching the Civil Rights Movement to get that reprinted, because even as little money as we SNCC people have, this is one of those groups that we donate to because it is so urgent in terms of making the new generation of people who understand what this history is and how it relates to them. I will say one last thing, the one final thing that I always like to end with was something we knew, and it relates to what Courtland said, necessary but not sufficient. What we understood is that if you do nothing, nothing changes for the better. If you do nothing, nothing changes.

Rucker: Wow, this has been a true treat. I want to say thank you, thank you, thank you.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Key Resources

In addition to the resources referenced above, here are some of the materials mentioned by the presenters and in the chat box.

LessonsTeaching SNCC: The Organization at the Heart of the Civil Rights Movement by Adam Sanchez. A series of role plays that explore the history and evolution of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, including freedom rides and voter registration. Who Gets to Vote? Teaching About the Struggle for Voting Rights in the United States by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca. A unit with three lessons on voting rights, including the history of the struggle against voter suppression in the United States. |

||

|

Digital CollectionsSNCC Digital Gateway An online collection of primary documents, profiles, a timeline, a map, and stories. The site was developed in collaboration with the SNCC Legacy Project, with Courtland Cox and Judy Richardson among the project leaders. Many of the people, events, and themes referenced during the session can be found at the site, including: music, Amzie Moore, June Johnson, H. Rap Brown, black panther symbol, and comic books. Civil Rights Movement Archive An extensive collection of primary documents and narrative histories of the Black freedom struggle in the South. Telling Their Stories: Oral History Archives Project with veterans of the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi. Education and Democracy: Complete online collection of the Freedom School curriculum from Mississippi, 1964. |

|

|

|

BooksHands on the Freedom Plow Stories from fifty-two women — southern and northern, old and young, rural and urban, Black, white, and Latina — about working for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle by Charles Payne. A people’s history of the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi. Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi by John Dittmer. A detailed, grassroots description of the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi. |

|

|

FilmsFreedom Song This feature film is based on the actual history of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), student activism, and voter registration in McComb, Mississippi. Recommended for high school students. Eyes on the Prize: America’s Civil Rights Years, 1954-1985 An award-winning 14-hour film series produced by Blackside and narrated by Julian Bond. Through interviews and historical footage, the series covers many major events of the Civil Rights Movement. Judy Richardson was the series researcher and series associate producer. |

|

|

ArticlesSNCC and/in the North by Say Burgin. Article in Black Perspectives on how Friends of SNCC chapters in the North provided vital support to the on-the-ground efforts of SNCC in the South and played a role in Northern civil rights struggles. What We Owe to the Black Women of this Powerful Civil Rights Group by Melinda D. Anderson. Article in Zora magazine on the central role of Black women in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). It features interviews with the three women pictured to the left (Jennifer Lawson, Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons, and Judy Richardson). |

|

MusicVoices of the Civil Rights Movement: Black American Freedom Songs 1960-1966 Many of the songs in this Smithsonian Folkways collection were recorded live in mass meetings. The freedom songs draw from spirituals, gospel, rhythm and blues, football chants, blues and calypso forms. The liner notes are by Bernice Johnson Reagon. The songs played to open and close the April 24 session were “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around” and “Woke Up This Morning with My Mind Stayed on Freedom.” |

|

The resources listed above were mentioned during the online session. Find many more more articles, lessons, books, and films on SNCC.

Reflections

Here are excerpts from the participant evaluations of the sessions.

What I learned.

I learned so much from hearing Courtland Cox talk about his history, and what significant events happened when he was in high school that led up to the SNCC being formed by college age students. It just really made it relatable to me as a high school history teacher, and how I can get my students to relate to the experiences of SNCC.

I loved how Judy Richardson “showed the personal” piece of the movement. It is different to read the information and see the timeline for the movement, but to hear the personal reaction to the hideous actions, changes things. It lifts it off the pages of history.

Too much to list here. But the power of narrative, solidarity thru song, political education through art, comics, the importance of power analysis, listening to the local, giving hope to youth organizers today…

I really enjoyed learning about how the comic books that Courtland Cox and others developed and shared to help educate. I think they are a fascinating primary source to use in discussion with students and to help make concrete the various small parts of organizing and activism — it’s not all marching.

The story from Judy about the importance of song in creating unity in the rural church story. There were also so many quotes that I took away from today’s session about the importance of righteous anger, that change is made by the minority, and the importance of building power and local power.

“The minority makes the difference.” — Courtland Cox. Also, I’m thinking about ways to show how music can be a unifying force AND a tool for resistance within the Civil Rights movement. I am also going to look into using comic books within the CRM as primary sources.

The best thing a teacher can do about power is to show a student that they have power within themselves. Also the statement about music being a tool of resistance and how music creates unity in a group.

Reminder about popular education techniques like songs and comics. From our breakout we named what SNCC teaches us- fearlessness, moving people from the heart, very young people did this work, importance of identifying needs in our own communities.

Courtland Cox’s disucussion of developing the comic for informing voters and letting them know they have power and how to exercise it. The development of the symbol also made me think about what the symbol/comics of today might be in the fight for social justice. Might ask my students to create one.

“If you do nothing, nothing will change.” What a powerful statement for our students to think about. I will use this to challenge my students to be the change they want to see.

Just the opportunity to hear first hand voices. Such an undervalued resource too often, our living historians.

The format.

EVERYTHING WORKS! This is the second one I’ve done and I’m very impressed.

I loved everything! I’ve never done a breakout session on Zoom — that was amazing! It was also nice to talk in a smaller group. If I made any changes, it would only be to allow for a little more time for the breakout sessions.

I appreciated the large group and break out rooms. I wasn’t sure I would like the breakout experience for such a short time, but I am SO GLAD you set that up.

I really appreciated the breakout groups because it allowed me to learn the different perspectives of people in other cities/states. I also liked seeing other students like me engaging in such a rich discussion.

I enjoyed hearning from guest veternas as well as from people in my breakout group.

That was exemplary. Well-scripted introduction, use of polls, assigned panelists who knew how to use the platform, brief and structured breakouts, use of chat. The shout-outs and musical play-off were ingenious!

Really liked the breakout room idea; saw that at least one professor had invited her students and was encouraging them in the chat box. Wish I had thought of that!

Speakers

Both Judy Richardson and Courtland Cox are in the leadership of the SNCC Legacy Project and played a lead role in the creation of the SNCC Digital Gateway.

Judy Richardson was on the staff of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Georgia, Mississippi, and Lowndes County, Alabama (1963-66) and ran the office for Julian Bond’s successful first campaign for the Georgia House of Representatives. She founded the children’s section of Drum & Spear Bookstore and was children’s editor of its Press. Her SNCC involvement has always been a strong influence: in her documentary film work for broadcast and museums (including the award-winning 14-hour PBS series Eyes On The Prize, PBS’ Malcolm X: Make It Plain, and Scarred Justice: The Orangeburg Massacre 1968); and in the writing, lecturing and workshops she conducts on the history and relevance of the Civil Rights Movement. Read more.

Courtland Cox became a member of NAG and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) while a Howard University student. He worked with SNCC in Mississippi and Lowndes County, Alabama, was the Program Secretary for SNCC in 1962, and was the SNCC representative to the War Crimes Tribunal organized by Bertram Russell. In 1963 he served as the SNCC representative on the Steering Committee for the March on Washington. In 1973, Mr. Cox served as the Secretary General of the Sixth Pan-African Congress and international meeting of African people in Tanzania. He co-owned and managed the Drum and Spear bookstore and Drum and Spear Press. Read more.

Jessica A. Rucker is an electives teacher and department chair at Euphemia Lofton Haynes Public Charter High School in Washington, D.C. She is a member of the D.C. Area Educators for Social Justice and was a participant in the 2018 NEH Summer Teacher Institute on the grassroots history of the Civil Rights Movement. She is a native Washingtonian and community accountable scholar with more than a decade and a half of youth development and community education expertise.

More Sessions

Read about and register for more sessions.

Please make a donation so that we can continue to offer people’s history lessons, resources, workshops — and now online mini-classes — for free to K-12 teachers and students. We receive no corporate support and depend on individuals like you.

Students may find the Canadian story of organizing against injustice interesting. Please check out the B.C. Labour History Centre Unit The On To Ottawa Trek. It includes music, film and storytelling about a group of men who travel across Canada in boxcars to protest treatment of the poor and unemployed, many who were forced to live in labour camps to survive.

Looking forward to this