Abby MacPhail, a high school teacher at the United Nations International School in New York City, shares a powerful story about her students’ study of Rosa Parks through the lens of identity and resistance.

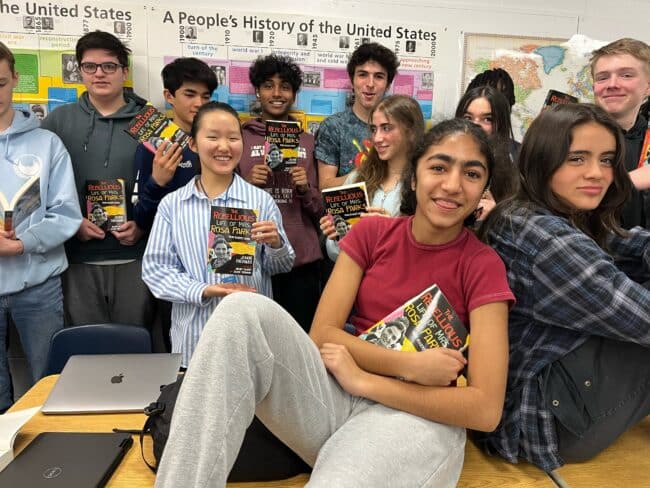

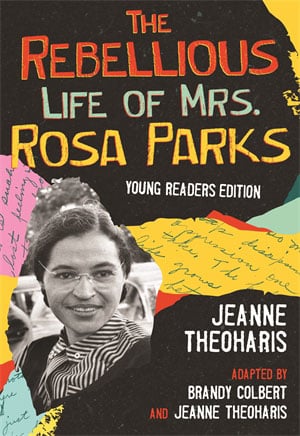

I used the young readers’ edition of The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks with my grade 9 students as part of our unit on “Identity and Resistance.” By learning about the life of Rosa Parks and about the Civil Rights Movement, my students were able to develop a deeper understanding of how groups of oppressed peoples have demanded their rights in the United States and of what factors enable resistance movements to cause change (two of our unit’s essential questions).

We began our unit with an introduction to the work of Dr. Erica Chenoweth. Chenoweth is a Harvard professor who studies political violence and its alternatives. Chenoweth looked at the success rates of 627 revolutionary campaigns — violent and nonviolent — over the past 120 years and found that nonviolent resistance is a stunningly successful method of creating change. Their findings show that over 50% of the nonviolent revolutions from 1900 to 2019 succeeded outright — while only 26% of the violent ones were successful.

We began our unit with an introduction to the work of Dr. Erica Chenoweth. Chenoweth is a Harvard professor who studies political violence and its alternatives. Chenoweth looked at the success rates of 627 revolutionary campaigns — violent and nonviolent — over the past 120 years and found that nonviolent resistance is a stunningly successful method of creating change. Their findings show that over 50% of the nonviolent revolutions from 1900 to 2019 succeeded outright — while only 26% of the violent ones were successful.

To introduce my students to Chenoweth’s work, we began by reading sections of their recent book Civil Resistance: What Everyone Needs to Know and learned about the four factors that they identified as making nonviolent civil resistance more likely to succeed: mobilizing a wide and diverse population, using a diversity of tactics, shifting loyalties from the government/regime’s pillars of support and remaining nonviolent and maintaining discipline and resilience in the face of state repression. Then, as we studied the Civil Rights Movement and read The Rebellious Life of Rosa Parks, we kept coming back to these four factors as we looked for evidence of them, and ultimately discussed and debated the extent to which the Civil Rights movement had been successful.

Beyond reading The Rebellious Life of Rosa Parks, we journaled and debriefed our responses in small groups, engaged in the Zinn Education Project’s mixer activity by Bill Bigelow, and watched some Democracy Now! clips of interviews with the book’s author Jeanne Theoharis.

After reading the chapter about Mrs. Parks’ life in Detroit, my students wanted to know more about redlining and segregation, so we devoted some time to exploring these topics. Their favorite part was when I handed out Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) maps of the five boroughs of New York City so they could look up their own addresses to see what grade they had been awarded. I found the maps on Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America, a digital repository of 225 U.S. “security maps” produced by the HOLC produced between 1935 and 1940. I had mine printed out on giant paper but these can all just as easily be viewed online.

After reading the chapter about Mrs. Parks’ life in Detroit, my students wanted to know more about redlining and segregation, so we devoted some time to exploring these topics. Their favorite part was when I handed out Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) maps of the five boroughs of New York City so they could look up their own addresses to see what grade they had been awarded. I found the maps on Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America, a digital repository of 225 U.S. “security maps” produced by the HOLC produced between 1935 and 1940. I had mine printed out on giant paper but these can all just as easily be viewed online.

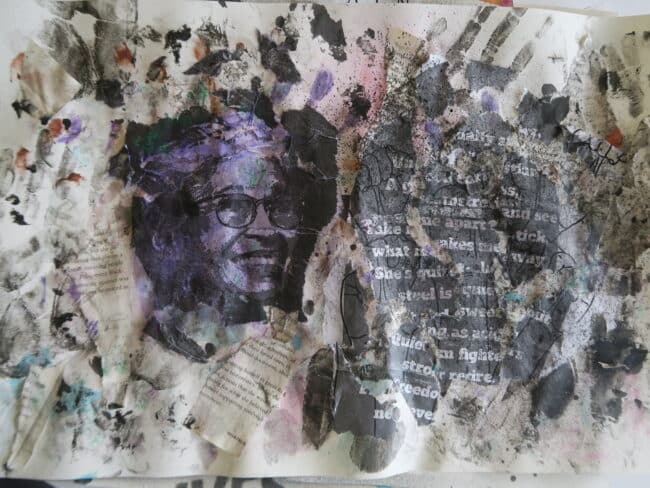

We ended the unit in the Art room. With the support of my wonderful colleague, Marc Smith, students turned their learning into works of art. They identified themes from the unit, found images on the internet and turned these into stencils, and then used words from the book to create collages. Tyler focused on the idea of resistance, stenciling the word equality in small letters next to the word RESISTANCE in large letters because as he explained, “while the amount of equality was small at that time, the amount of resistance was big.” Stella emphasized the theme of distortion, blurring words from the book and cutting off half of Rosa Parks’ face in her image to illustrate how the single focus on Park’s unwillingness to give up her seat on the bus, distorts her overall story.

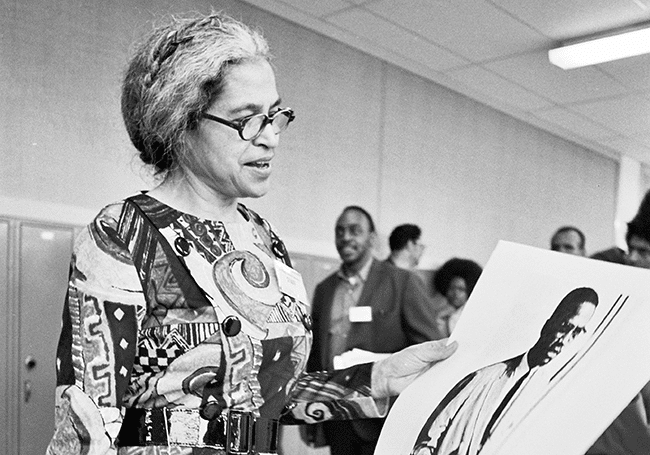

And ultimately, this was one my students’ most important understandings from this unit, as Hanna so eloquently summed up in our final debrief,

What I learned most was that Rosa Parks was actually a lifelong activist and her life shouldn’t be put in a box of only one moment where she would give up her seat on one day, but rather that she was a part of a bigger movement, and a part of the NAACP to help improve the civil rights of Black people at the time.

You have now spent hours filming, watching and editing the footage from our class. What is your biggest takeaway from all of this?

Her response:

It made me question what I thought I knew about history. Now I realize that we have to think about which parts of the story are not being covered.

Abby MacPhail is the author of the lesson, Dirty Oil and Shovel-Ready Jobs: A Role Play on Tar Sands and the Keystone XL Pipeline, originally published in the Rethinking Schools magazine.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn