On Monday, November 14, 2022, historian Matthew Delmont shared stories from his new book, Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad. Delmont was in conversation with historian Jeanne Theoharis. Thanks to Delmont’s generosity, every teacher who attended the Teach the Black Freedom Struggle class received a copy of the book.

Here are several reflections from participants about what they learned and the session overall:

I appreciate the discussion of the significance of the Lincoln Brigades and their context for WWII. I am also so thankful for the resource drop of the Black Quotidian Project.

I liked the idea of expanding the timing of WWII to before Pearl Harbor and including the Civil Rights era. I also appreciated the discussion of Black women during and after the war.

I never thought about the different coverage of 1930s events and the rise of fascism in white and Black newspapers in the U.S. I want to research this in more depth. I’ve also never learned about the 6888th all-female Black Battalion.

The idea that timelines, start and end dates, are racialized too. Black soldiers were fighting fascism at home long before Pearl Harbor.

This was my first time participating in this class. I was nervous as an elementary educator. I got a lot out of it, though, and the other participants made me feel very welcome.

Event Recording

Check out the recording of the full session, except for the breakout rooms.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: On behalf of the Zinn Education Project, we’d like to welcome everybody to our class with Matt Delmont on “We Return Fighting”: The Black Freedom Struggle during World War II. I’m really excited for this conversation. Some of you are joining us for the first time, and some have participated since we launched this series. It really is special to get to build this community over time with all of you. Thank you for being in virtual community with us.

I know I myself have missed a couple sessions. I’ve been struggling with long COVID now for over three months, but I had to come back and help introduce this session because I just love this community that’s grown up around resisting the anti-history laws and teaching the truth. We’re going to hear some of that today. Today’s class is hosted by the Zinn Education Project, which is coordinated by Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change, and it’s part of our Teaching for Black Lives Campaign that everyone should check out on our website, [where] we offer free downloadable people’s history lessons that probably many of you have used in middle school and high school, all available on that website. We are also very fortunate to have ASL interpretation with us this evening provided by Krystal Butler and Kaylee Teixeira.

Thank you for being with us. Before we begin our conversation, we want to find out who’s in the room and go through our plans for our time together. So, we’ve posted a poll to find out how many teachers are with us, librarians, teacher educators, historians, parents, students, educators of all kinds. And we will have those numbers for you in a moment as they are rolling in right now. Many of you have multiple roles, so if you have several roles just pick your primary one.

We also have members here from our Teaching for Black Lives study groups. We have around 100 study groups around the country. This year, if you’re in one of those study groups, please put T4BL after your name. Throughout the session, we want you to use the chat box to post questions and comments, resources and ideas. And we’ll do a short evaluation at the end. In about a week, we will share the full recording of this session and all the resources that you shared in the chat box. So please help us there. Also, you can tweet what you’re learning, put it out on social media about the things that you have learned and invite others to join us in this monthly course. Then after about 25 minutes, we’ll pause so you can meet each other and talk in small groups — this is really where the deep learning happens, and where you take the lessons that you learned and figure out how to apply it to your classroom and meet other great educators who have ideas about how to do that. So, we really want to find out how those breakouts go and then we’ll come back together and hear from everyone again.

So, please join me in welcoming Jeanne Theoharis, who will conduct the interview this evening. Jeanne is a distinguished professor of political science at Brooklyn College and author of The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, among other of my favorite books. She’s also the co-founder and curator of this series. Really glad that Jeanne could come in and help with this session today. Our guest historian Matt Delmont is associate dean of international studies and interdisciplinary programs at the Sherman Fairchild Distinguished Professor of History at Dartmouth College. Delmont is the author of four books. His newest book, Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad was published in October. Welcome to you both. Thank you for being with us. I’ll turn it over to you, Jeanne.

Jeanne Theoharis: Well, thank you. Thank you, Jesse. It’s so wonderful to be here. This is where, now two and a half years into this series, it continues to amaze me that we get to be together and learn together. So thank you everyone for making time. Again, this is the part of the semester where things start to get hard, and it’s easy to not want to come on a Monday night, or Monday afternoon. So thank you for being with us.

I’m so delighted to get to be in conversation with Matt Delmont. Matt and I have been friends and colleagues, and we’ve edited and written things together. It’s so fun to be here to talk about this new book. And everyone knows this — this is Matt’s new book, and everyone who came tonight, because Matt had research funds last year that he did not use and he decided to use those research funds to make it possible for teachers to have this book. So that’s pretty incredible. And it will obviously really change how we all teach this history. So thank you, Matt, for being here. Thank you for that incredible generosity. Welcome.

Matt Delmont: Thanks Jeanne! It’s such a great pleasure to have a chance to talk with you about the book. For folks who are on the call, Jeanne is one of my favorite historians in the whole world and her profession, and she’s a good friend. So, it’s a real pleasure to have a chance to talk about the book with her. I thank Deborah and Jesse and everyone with the Zinn Education Project for all the work they’ve done to organize this and to help us support getting the book out into the hands of teachers. To see teachers post receiving their copies of the book in their classrooms and know everything that those teachers and librarians are going to be doing with the book is — you can’t ask for more as a historian. I’m just thrilled to have a chance to talk with this group tonight and I look forward to the conversation questions.

Theoharis: So, where I want to start is actually where this book started, which was actually your previous project — and you can tell us a little bit about it. It was called Black Quotidian. And for over a year, Matt has — he’s one of the most disciplined scholars I know — and so every day for over a year, he would post a piece from the Black press from that day in history, or he would get his students to do it. And it became this incredible pedagogical lesson as well. But it was a way to kind of look at the expanse of Black life, of Black history, of Black struggle. But certainly I remember one of the things that comes out of that project is this project, which is that as you were combing through all of these articles, one of the, I feel like biggest revelations you told me was how you come upon the history of World War II. So maybe you can tell us a little bit, both about Black Quotidian, but also how that becomes the genesis for this?

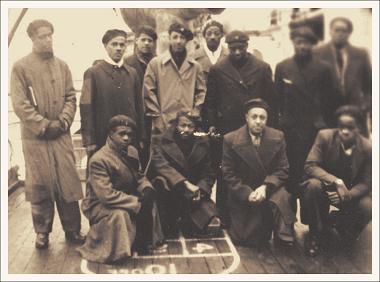

Delmont: Yeah, thanks for starting there, Jeanne. So, if you went online and searched for Blackquotidian.org, it ended up being a publicly available book, an open access book, published by Stanford University Press. It really emerged from my own curiosity and frustrations as a teacher. I was teaching African American history and felt like a lot of the examples I was giving — while they’re really important — they felt repetitive in some ways. So, we talked about it Ida B. Wells, and I’d talk about the lynching of Emmett Till, talk about the organizing around that. But I didn’t feel like I was doing justice to the full range of Black experiences. I felt like I was using a lot of the same examples year in and year out. And so, as a way to try to explore different pathways and really learn new things myself, I started going through these historical African American newspapers. I’ll just pick a paper from 1935, or 1942 to see what people were reading about in Cleveland, or Pittsburgh, or Chicago. And it really did become the foundation for this project on World War II. Because when I got to these papers from ‘41, ‘42, ‘43, I kept coming across examples of Black men and women who volunteered or drafted into the military. These weren’t famous people at all; these were just average, everyday folks. And they were profiled in Black newspapers. They would have a little snapshot photo or a brief write-up that so and so got drafted from Cleveland, or this person got drafted from Los Angeles.

Seeing hundreds and hundreds of those examples was eye opening for me, because it was not the kind of everyday material about Black life during the war that I’d ever encountered before in textbooks or in the other materials I was using in my class. So it made me curious, and it’s actually what really sparked my interest in what more is there to understand about the African American experience during World War II. It really did launch me on the research process that became this book.

Theoharis: Thank you. So I want to start big, and you know and most of the people on this call know that one of the persistent questions in my research are the myths we have about history, the misuses of history. I think, just like many people in this space, we’ve spent a lot of time talking about the myths of the Civil Rights and Black Power movements. I think there are a lot of myths and ways we think about World War II that are really both misapprehensions of that history and really misuses of that history. So, I wondered if you could tell us maybe two or three ways we teach and learn World War II wrong and what are the stakes of that wrong history and what changes when we see it differently?

Delmont: That’s a great question. The two that come to mind first, for me, are the idea that somehow America was more unified as a nation during World War II. I think that one of the common misconceptions that we often have when we talk about the World War II era is that the country came together and put differences aside to fight a common enemy, to win this war against Japan and Germany and the Axis powers. When you actually look at the historical evidence, we know that’s not true. That there were deep, deep divisions across many components of American society, particularly in terms of race. During the war, obviously, Jim Crow segregation [and] racial apartheid was still the order across the U.S. South, and there were other forms of racial discrimination that very much resembled the kind of Southern form of discrimination happening all across the country. In New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Black people could look around and understand that they were not living in a country that treated them as equals. That was not a not surprise to any Black American during the war, and it came through very clearly in Black newspapers at the time.

In 1943 alone, there were more than 240 race riots or racial clashes all across the country, in small towns and big cities and military bases. So this idea that somehow World War II was a time of national unity — that everyone came together to fight a common cause, to fight to win the war — it just isn’t true. I think the damage it does for us today, if we look back and think that World War II was somehow a simpler time or a more peaceful unified time, it makes it seem like protests around racial justice today are somehow surprising, or they’ve come out of thin air, they’ve come from nowhere. If you tell the actual history about what happened in World War II, it’s clear that these battles have been going on for generations. Part of the urgency of the Black Lives Matter movement in the past decade is that people’s grandparents are fighting the same battles in the same streets for decades and decades, going back to World War II and earlier.

And the other one, the other big myth I would say I hope the book helps to put in a different context is the idea of the “Greatest Generation.” If you actually go back and look at Tom Brokaw, his book that helped to popularize that phrase, it’s actually a much more complicated, nuanced book than I think that shorthand “Greatest Generation” has become. He does talk about Black veterans, he talks about Japanese Americans who were interned. But that shorthand of the “Greatest Generation” almost becomes like a shield that’s made it impossible to say anything critical about that entire generation of Americans.

It’s particularly troubling because Black veterans who fought in World War II had a very different experience than white veterans did. So I’m largely ambivalent about whether we should even maintain the idea of the “Greatest Generation,” but for better or worse, I think that term is with us. I think my approach to it is to foreground the experiences of Black veterans from that same generation. Because they were not only fighting that same military battle to defeat the Nazis, but they came home and then fought for civil rights at home. And I think if we foreground those experiences, we can see that, to many white Americans of that generation, the so-called “Greatest Generation,” were too ready to condone and maintain white supremacy at home. They condoned Jim Crow segregation, they condoned many forms of racial discrimination that had serious long-term negative consequences for Black Americans and other people of color in the United States. So, I hope that by foregrounding and putting into focus the experiences of Black veterans and Black Americans during World War II we can come away with a much clearer sense of really how fraught that time period was in our nation’s history.

Theoharis: I mean, this is actually not a question I said I was going to ask you, but one of the things that I’ve been struggling with during COVID is that it’s made me feel like we have to go back and rethink the “Greatest Generation,” because there’s also this idea — like in that myth that you’re talking about of how unified we are — there’s a myth about how everybody’s sacrificing for everybody else. And I was wondering if you could maybe talk about that a little bit, vis-à-vis, because I think part of the myth of the “Greatest Generation” is just this idea of the country putting the country first. Part of what you’re I think doing in this book is saying, “Well, a lot of people, what their idea of the country or what they were going to put first was very racialized and in fact, much more like, We weren’t just sacrificing and buying war bonds and not eating meat just for everybody.” And so I just, I guess, I want you to tease that out a little bit more.

Delmont: Yeah, I think like with most historical myths, there are serious grains of truth that underlie the myth. And so, it is the case that Americans, white Americans, sacrificed a great deal during the war; the rationing was true, the buying of war bonds was true. The fact that so many American citizens got drafted into the military and then fought and gave their lives to help defeat the Nazis — that was an important battle that had to be fought. So I think those elements are all true. I think what changes though when you foreground issues of race and racism is that there was a limit to how much people were willing to sacrifice. And they drew those lines in very strange ways, or maybe not strange — in ways that end up producing some very negative outcomes for Black Americans and other people of color.

One of my favorite quotes from the book is Roy Wilkins, who was one of the leaders of the NAACP, and he said, “White folks would rather lose this war than give up the luxury of race prejudice.” And I think the truth of that is revealed in the fact that the entire military was segregated during the war. Segregation made no sense from a strategic or tactical perspective. It was overly complicated and took a huge amount of resources to make sure everything in the military was targeted. They had to segregated latrines, barracks, and recreation facilities — it was onerous and time consuming and absurd when you actually got down to the practical reality that it was someone’s job to make sure that everything was segregated throughout the war.

In terms of the defense industries at home, there were a number of hate strikes that were carried out by white workers all over the country. These were strikes that were not authorized by unions, but white workers chose to stop working in these defense industries rather than allow Black workers to join the workforce. These were two to a dozen Black workers who got hired. Or in Baltimore, they refused to work because they integrated the bathrooms. So at a time when, theoretically, America is banding together to sacrifice everything for the war effort, you had war plans that were making trucks, ammunition, and tanks grind to a halt for weeks at a time because white people couldn’t use the same bathroom as Black people.

It’s those details that I think give the lie to the sense that somehow America was giving everything to the war effort. If America was truly giving everything to the war effort they would have desegregated the military as soon as the United States entered the war. They would have desegregated the defense industries because that was the best way to take advantage of the tremendous capacities of Black Americans and people of color that they had to give to the war effort. The military turned away Black Americans with PhDs from Harvard. They took people who had advanced language training and other skills and made them cooks rather than taking advantage of the skills they had to deploy in the military effort. There are countless examples like this that, I think, really reveal that idea of sacrifice. It was true in some cases, but as soon as it ran up against a willingness to change anything with regards to racial hierarchies, and the racial status quo, that was the breaking point for the majority of white Americans at the time.

Theoharis: Part of, I think, what the book shows is also that the very timeline of World War II looks different when we center the Black experience. Again, as you know, this call is mostly educators, how do we teach the timeline of World War II differently if we begin or center the experiences of Black Americans and the viewpoints of Black Americans?

Delmont: So we have to start by teaching World War II before Pearl Harbor in 1941. If you looked at a Black newspaper from the 1930s, you would see extensive coverage about the rise of fascism in Europe. In 1933, ‘34, ‘35 there were dozens and dozens of articles and editorials describing in some amount of detail what was going on in Nazi Germany — how Adolf Hitler rose to power and how he was explicitly pointing to American racial policies to help justify his treatment of Jews in Europe. Even more specifically, Black newspapers are making connections between the kind of treatment of Jewish people in Europe — the segregation on train cars, the theft of property, the physical violence — and what’s going on in the Jim Crow South at the same time. And so, already by the 1930s, there are explicit claims to be made that the second World War has started because they see the rise of fascism in Europe. When Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935, that is like a lightning bolt across Black America because Ethiopia is the only independent African nation at the time. So it figures very prominently in the imaginations of a lot of Black Americans. The fact that a fascist regime in Benito Mussolini’s Italy invades Ethiopia, and that the world community largely does nothing about it, is shocking. And again, the headlines say the second World War started.

A couple of years later with the Spanish Civil War, when General Franco’s fascist forces staged a military coup against the democratically elected government of Spain. There are more than 80 Black volunteers who go to fight in the Spanish Civil War, and that gets covered in Black newspapers all across the country. So in that decade before Pearl Harbor, for everyday Black Americans all across the country, they’ve seen article after article, they’ve been in conversations, they’ve heard on the radio that war has already broken out in Europe and it has serious consequences for the United States, even if the United States hasn’t officially entered the war militarily yet.

And then on the other side, we have to teach the war as not ending in 1945. That, yes, the military battles end — Germany and Japan surrender. But that whole generation of Black veterans who come home and start fighting for civil rights, they would never say that the war ended in 1945, because for them a different battlefield in the war just continued. So foregrounding the experience of Black Americans really troubles this idea that the war can be neatly bounded from 1941 to 1945. That’s really just the American military conflict piece. The broader social implications of fighting for freedom and democracy, both in the United States but globally, really pushed the boundaries of that timeline in two different directions.

Theoharis: Just in terms of the beginning, and what you were saying about the Black press, how has the Black press — If you were reading like the Amsterdam News and The New York Times or The Eagle and The Sentinel, and then the LA you know, are you getting more coverage, for instance, of Nazism in the Black press in the 30s than in mainstream white presses? Just to kind of clarify and push your point, how does it compare?

Delmont: You’re getting much more clearly worded and clearly argued coverage in the Black press than you see in a lot of the white press project. I would recommend for folks, if they’re not familiar with it, the U.S. Holocaust Museum and Memorial has a project they’ve done called History Unfolded, that’s gathered newspaper articles from people all across the country of how American newspapers were covering the Holocaust as it unfolded. So I wouldn’t want to say that mainstream white newspapers didn’t cover events in Europe, but they didn’t cover it with the same amount of moral clarity as Black newspapers did.

I think that’s the thing that Black newspapers brought to bear much earlier than white newspapers did, again, because they recognized that what Hitler was doing had a model, and it had a model that was going to have terrible, terrible consequences — not just in Europe, and not just for Jews as the primary targets of it — it was going to have very terrible consequences for the world. Because they see how it’s already happening in the United States, in the South particularly. So, the frequency of the coverage and the moral clarity of the coverage is much, much sharper in the Black press than it was in a mainstream white paper.

Theoharis: Mostly tonight we’re going to be focusing on sort of the African American experience — the War at Home — before, during, and after the military conflict. And people need to read Matt’s book to get more of what’s happening in Europe, and the battlefield side of it. But I wanted to ask one question, which is where the book starts, literally, which is with the Lincoln Brigades and both why you started there, and what that shows us? Why did people join? But also the criminalization of the Lincoln Brigades and — what I mean, it’s another moment where a different view into that whole era, if they had been treated differently. So, could you give us a little bit about why you start there and what the Lincoln Brigades were?

Delmont: So for people who aren’t familiar, the Lincoln Brigades were a group of American volunteers who went to fight in the Spanish Civil War. There are thousands of volunteers from all over the world who joined the fight of the republican forces to fight against fascism in the Spanish Civil War, and the Lincoln Brigades were about just more than 3,000 Americans who fought in that. Of those, more than 80 were Black Americans.

Langston Hughes, the famous poet, becomes a war correspondent for The Baltimore Afro-American because he’s fascinated by this idea that Black Americans from New York, from Alabama, from Georgia would uproot themselves and travel to a country they’d never been to before to fight in the Civil War. And I literally mean fight — this was frontline combat that they were taking on. They were risking their lives and many of them lost their lives fighting this conflict. Hughes goes over there and reports on some of the people who were fighting. A couple of them that stand out that I can share are: there’s a woman named Salaria Kea, who was originally from Akron, Ohio, but she trained as a nurse at Harlem Hospital. She becomes concerned about what’s going on in Europe, first with the timing of the invasion of Ethiopia, then she works with a number of Jewish doctors who tell her about what’s going on in Germany and how Hitler is treating Jewish people in Germany. She tries to volunteer for the Red Cross, but they turn her away because of the color of her skin. They say she’d be too much trouble to make space for her in the Red Cross. So she becomes the only Black nurse to be part of the Lincoln Brigades, and she’s there attending to soldiers who are coming back from the frontlines. She was to serve as a nurse in the U.S. Army during World War II, and she’s one of the people that Hughes writes about.

Another one that really captured his attention was a guy named Walter Garland, who is from Brooklyn, New York. He was an officer in the Lincoln Brigades. Part of the reason the Lincoln Brigades figured so powerfully for a lot of Black Americans is because at that time the U.S. Army is segregated and they’re not allowing Black men to participate in combat; they’re put in these more menial roles behind the scenes. Garland, in contrast, was an officer in the Lincoln Brigades and he’s leading an integrated unit where he’s got American troops, English troops, Irish, Jewish, Cuban, Mexican. It’s almost like the United Nations unit that’s under his command.When Hughes travels over there, he gets to see Garland giving the commands and marching his unit in a parade formation through town. It captured his imagination because it’s a Black American leading this integrated unit, integrated combat unit, in a way that just wasn’t possible in the United States.

A number of those Lincoln volunteers, both Black and white, go on to serve during World War II, including one named Edward Allen Carter, who wins the Medal of Honor, posthumously is awarded. But as you noted, Jeanne, the politics that led a number of volunteers to Europe were leftists, and that was an extreme concern to a lot of American politicians. So, rather than celebrating the bravery or courage of these volunteers who go and risk their lives to fight against fascism in Spain, when they come home, they’re harassed by the FBI, and are tracked and surveilled because their political positions are deemed to be too controversial in the U.S. at the time. It’s an important place to start, because it shows that Black Americans were among the first to literally take up arms to fight against fascism. And it gives a clear model of what was possible in terms of American military participation that wasn’t yet welcome within the American armed forces.

Theoharis: Sticking still with the earlier timeline, I wanted us to talk a little bit about the March on Washington movement. That, in many ways, part of this early period is the story of World War II and the ways that the United States initially gets out of the Great Depression by becoming, in some ways, the industrial engine for the Allies, and just supplying. And Black Americans both recognize what’s happening, but also recognize the real dangers that Black Americans are going to get left out of this industrial resurgence that’s happening in the United States. A. Philip Randolph and many people we will see again later in the 60s are at the forefront of basically — well, you tell us. Tell us, what do they see as the danger or the threat, and what do they do? And in many ways, how is this really the beginning of the kind of modern Civil Rights Movement?

Delmont: In the lead up to World War II, before the United States officially enters, after Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt announces that America is going to be “the arsenal of democracy,” that it’s going to provide all of the supplies that the Allies are going to need to fight and win the war. What that means, everyone understands, is it’s going to mean jobs. That this means that the defense industry is going to be created all over the country, that factories are going to transfer from whatever they made previously to starting to make ammunition and tanks and trucks — all these goods that the Allies are going to need. If things were left untouched, Black Americans were going to get locked out of that great boon of jobs that would almost all go based on how the unions were structured and how prejudice was happening within these factories and defense industries. They’re going to get locked out of this huge windfall of resources and jobs.

A. Philip Randolph was the leader of the largest Black union in the country, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. In early 1941, he announces a March on Washington. He says unless President Roosevelt agrees to make sure there’s not discrimination in the defense industries, he’s going to lead 100,000 Black Americans in a March on Washington. What’s so remarkable when he announces it is that it’s shocking to both white politicians, but also to a lot of Black Americans. The idea that you could bring together that many people, self-organized among only Black Americans, to demonstrate their political power and to embarrass the White House in that way was a threat that hadn’t ever been made on that scale before. Between the time when Randolph makes the claim in March 1941 and the summer of 1941, it receives a huge amount of coverage in Black newspapers. He’s traveling around the country, and he’s working with organizers to do all of the groundwork to create these March on Washington chapters in all different parts of the country. That’s where a lot of the actual power comes from; it’s not just him standing on a soapbox saying, “I’m going to make this happen.” He can point to people on the ground who are doing the organizing, who say that they’re going to be able to turn out 1,000 people from Oakland, 2,000 people from Houston, who are all going to make this trip to Washington, D.C.

Eventually Randolph gets into the White House and has a sit down negotiation with President Roosevelt. Initially, Roosevelt isn’t going to do anything. He says, “If I give this to you, everyone’s going to come in here and demand something.” But through a high stakes negotiation Randolph was able to eventually persuade Roosevelt to sign an executive order that, at least on paper, has non-discrimination provisions in defense industries, in exchange for Randolph calling off that March in Washington. The reason it’s important in our broader understanding of Black Freedom Struggles, though, is that it really creates some of the early infrastructure for organizing. These March on Washington chapters, they don’t go away; they’re there, and they take on different shapes. A lot of those organizers and activists have long lives in Black Freedom Struggles — Bayard Rustin among the most important and most famous — that literally provides the infrastructure and architecture for the March on Washington in 1963.

The other reason I think it’s important is that it was a tremendous display of political imagination for Randolph to threaten — and to be able to threaten it persuasively — that he was going to lead this massive March in Washington entirely changed the dynamic of how Black activists engaged with politicians in Washington, D.C. that even though he never had to actually carry out the march. Just the fact that he could persuasively argue that he was going to do it added a new type of leverage that Black activists then hadn’t had previously.

Theoharis: I think [there are] two questions there. One, I think, could you say a little more? Because I think part of that is also the way that it expands what’s possible, that like all of a sudden you’ve seen the President bow to a movement. So, how is that going to shape this next 20 or 30 years of what is possible to imagine, of what is possible to ask for? I guess my second question is that this is also a contested moment that Randolph takes a deal that [Bayard] Rustin doesn’t agree with, so that this unity is not even a unity. There’s so many ways that this history is more complicated than we thought. So, you could go in either or both of those directions.

Delmont: Yeah, maybe the second part first. I mean, it’s a great point, right? For everything that Randolph and those other leaders accomplished with that, it ends up being something of a hollow victory. At the start of that call for the March on Washington, they’re also calling for the desegregation of the military — which obviously doesn’t happen until 1948, with an executive order from President Truman. But even the executive order that Roosevelt signed — Executive Order 8802 — initially, it’s greeted with great fanfare in the Black press by a lot of Black leaders. It’s described as the second emancipation proclamation by some folks. But when it actually tries to get implemented, the commission that’s put in place to try to investigate these claims of discrimination is an organization called the Fair Employment Practices Commission, the FEPC, they don’t have anywhere near the resources or manpower to be able to investigate the thousands and thousands of claims of discrimination that are coming up after this executive order is signed. So, it’s a case where on paper it looks like it’s going to do great things, but then the reality is it doesn’t produce as many results as was hoped. And it requires Black activists and organizations all across the country to continue to protest at their local factories to actually get some of the jobs that are meant to be promised there. So I think it is a good example that anytime you have these kind of high stakes negotiations, there’s something that’s lost, or there’s a question about how much can you get at any point in time. Then that gap between the words on paper and the actuality of what can be implemented is often quite vast. The first piece, I think it did help to demonstrate what a large group of Black Americans with powerful leadership could get from the White House, or get from other political figures. In many ways it set the model for the kind of negotiations King and others had with the Kennedy administration.

Theoharis: So, I think where I wanted to start next was sort of now getting us into World War II and this idea of the Double V, and sort of what was it? I mean, why do Black soldiers have tattoos of the Double V? [Can you talk about] how it becomes also similarly surveilled? Just tell us about the campaign itself and its significance.

Delmont: So, the title of the book is actually taken from a letter that helps to launch the Double Victory campaign, which is written by a guy named James Thompson, who’s a 26-year-old from Wichita, Kansas. He writes this letter to the Pittsburgh Courier, which was one of the largest and most influential Black newspapers. He’s writing in late December 1941, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, because he knows that he and other Black Americans are about to get drafted into a segregated military. So he writes this really powerful, probing letter in which he asks a series of questions, including, he says, “Should I sacrifice my life to live half American? Is the America I know worth defending?” And that phrase, “Should I sacrifice my life to live half American?” it just really stuck with me for the seven years I was working on this book, and so I chose Half American as the title. What Thompson was asking was a really powerful question, because he recognizes he’s going to get drafted into a segregated military and potentially be asked to fight for, and maybe even die for, a country that doesn’t even treat him as a full citizen.

The Courier uses Thompson’s letter to launch the Double Victory campaign, which becomes the rallying cry for Black Americans during the war — that they’re fighting for both victory over fascism abroad, but also victory over racism at home. It’s one of the things I’ve taught about for more than a decade in my classes, but when I actually paused and spent time thinking about that idea of a truly double victory, it’s a really powerful framing for how Black Americans thought about the war — because they meant both parts of it sincerely. This victory over fascism abroad, I think is powerful because Black Americans, much more so than white Americans, understood what fascism was about.

One of the fascinating things — until I got into the research for this, I didn’t really understand that other than Jewish Americans and Black Americans, a lot of everyday white Americans didn’t really have a clear sense of why America was even fighting the war. They said as much in the public polling. They wanted revenge against Japan, but the question of “why they’re fighting in Europe?” a lot of white American just kind of threw up their hands and said, “I don’t know. We don’t know what’s leading us there.” So that desire to have victory over fascism abroad, Black Americans really meant it because they understood what a dire threat fascism was. But then again, importantly, linking that to victory over racism at home, I think that’s where we see that the war didn’t end, and couldn’t end, just on the military battlefields because it didn’t do much good to defeat Nazism abroad if you had to come home and face almost the exact same version of white supremacy at home. So that’s why Black veterans were so dedicated to fighting for civil rights here on the home front.

One of the things I tried to argue in the book is that if we take the Double Victory campaign seriously, it becomes pretty apparent that for a lot of white Americans, they’re really only fighting a single victory campaign. They wanted a military victory and then a return to the status quo. They wanted America as it was before the start of the war, and that was really the exact opposite of what Black Americans wanted. They didn’t want to return to a country that treated them as half American. That’s where you can see a lot of the tensions that emerge after the war. There are two very different ideas about what the war is about, and what vision of America should come to fruition after the war.

Theoharis: Right. We can really talk about how the United [States doesn’t] win the war, because it’s like, we only won half the war, right? I mean, I think we all grew up and it’s like, well, first of all, there’s the European front, and then there’s the Pacific front, but there’s also just the U.S. front that we don’t actually win. Mark Levy in the chat wants to know a little bit more about how vets and other war workers return and what they do to engage in civil rights and freedom struggles in the 40s and 50s.

Delmont: Both on the home front and for the veterans who were returning, a lot of that organizing takes place during the war years. So, some of the figures who become more prominent in the 1950s and 60s — people like Ella Baker — really play important roles, forming some of the infrastructure for civil rights during the war. During the war, Ella Baker is the head of branch organizing for the NAACP. She’s traveled all across the country, organizing different local communities to form their own NAACP branches and to sign up new members. And she’s tremendously successful — the numbers and branches increase dramatically over the course of the war.

One thing that’s important about Ella Baker in this story — and why I was so excited to include her alongside this military history — is that her vision of leadership was really a direct counter to how the military thought about leadership. Ella Baker believed that Black Americans from all walks of life had the capacity to be leaders; that you didn’t just need to be a doctor, a lawyer, or a professional class person. That sharecroppers, everyday Black folks who would be at the barbershops and beauty parlors and churches, they could be leaders, and they were leaders. She’s doing that at the exact same time that the military is saying Black Americans, no matter what their education is, really can’t be officers. They don’t have the capacity to be leaders. She’s showing the light to that statement.

So my favorite sources I found doing research, and these are in Ella Baker’s papers at the Schomburg, were part of that Double Victory campaign. Maybe the clearest illustration of it was that some of the new members who signed up for the NAACP were actually active due to active duty servicemen and women who are in Europe or in the Pacific. They’re essentially passing the hat around, or passing the helmet around, to raise money for civil rights battles at home while they’re stationed in Normandy or on islands in the Pacific. It’s such an apparent illustration of how the home front battles and military battles were always intertwined for these Black men and women.

In terms of what happens after the war, probably the defense industry workers, they lose their jobs, because it’s the last hired, first fired kind of policies. But the Black veterans who come back, they become leaders in service organizations all across the country. A lot of them credit the kind of training they received in the military in terms helping them organize both the sense of how to use firearms and the sense of bravery in the face of people who would be using firearms against you. And the kind of very basic logistical aspects of what it means to organize dozens and dozens of people towards a common goal.

Theoharis: We can’t ever have a conversation without talking about Rosa Parks, but obviously Rosa Parks’ NAACP history starts during World War II, because of World War II. Her brother is serving in the Pacific, she can’t register to vote, then she goes to one of these Ella Baker sort of organizing and is really activated. But there’s no way to understand her decision to go to Montgomery separate from this kind of contradiction of her brother serving and risking his life and then just not being able to vote at home and not having any type of full citizenship at home.

Delmont: One of the examples I cite from from your book on Rosa Parks is the anecdote about how on the the base in Montgomery, the Maxwell Air [Force] Base — because it’s later in the war, they’ve desegregated the buses on that base, and she’s able to ride in any part of the bus she chooses — when they get to the edge of the base then have to transfer in the city of Montgomery, she has to sit in the back of the bus. I think the way you framed it is what she described as having to go from first class citizenship — where she can sit wherever she wants — to second class citizenship — where she has to go to the back of the bus — just in the course of one city block.

Theoharis: I’m talking about imagination, right? Both how one’s imagination changes, because it’s like, “Oh, wait, I can sit here next to my friend, talking to my friend, right?” Because part of it is she’s working with a white woman there, and they’re riding the bus. And then this. So I mean, she talks about her imagination changing and then that being, like, physically segregated.

Well, this was a question I was going to ask you when we were having the breakout groups: My students always want to know, why do Black people serve and want to serve so much? And I think, and I teach in a college that’s like a quarter Black, a quarter Latino, a quarter Asian American, a quarter white. They’re just like, “That doesn’t make sense.” So, maybe you can talk to us about why, even in the midst of this half Americanness or second class citizenship, why do Black Americans push a lot of barriers to be able to serve?

Delmont: Going back to that quote from James Thompson — the “should I sacrifice my life to live half American? Is the America I know worth defending?” — Black Americans answer that question in hundreds of different ways. There were a number of Black Americans who didn’t accept their draft status. One of the realities is once the draft happens, Black people or other Americans have no choice — either they can accept the draft status and serve or they can risk going to jail. It’s not unlike the choices that people encountered during Vietnam, and there were thousands of Black Americans who chose jail over military service.

Most famously, Bayard Rustin — who was a Quaker and a pacifist, and was opposed to all wars — but he was also opposed to fighting for the United States, given what he understood about the racial policies and treatment of Black people in that state as opposed to fighting he served three years in a federal penitentiary rather than serving during World War II. There are examples of college students from Morehouse and Howard who declined their draft status and became almost local heroes among their peers, even as their peers are going off to fight the war. So I certainly wouldn’t want to give the impression that all Black Americans accepted their draft status and went to fight the war. There are thousands who resisted it.

I think for other Black Americans though, one of the reasons there’s a desire to fight for the opportunity to serve in the military is that it means jobs — that there was payment that went along with military service, there was training that went along with military service, and that the military was taxpayer funded. So one of the things that activists kept saying was that it makes no sense for us to not be able to partake in the benefits that are going to come from this military service, if we’re paying into it as taxpayers. For some people, there was a sense of patriotism — they wanted to fight for their country. Not unlike how a lot of white Americans want to fight for their country, even while always understanding that America had deeply entrenched racist policies. And then, I think for some number of people also, they come from families where military service had been a tradition, and recognize that military service had often been linked with American identity and claims of American citizenship. I think that motivated some Black Americans to volunteer as well. But I think the reality is, once the draft starts, it’s very, very hard to fight back against that, and that’s why more than a million Black Americans end up serving during World War II.

Theoharis: Again, since this is a community of educators, if you were going to pick a primary source to sort of teach this history of the Double V and of the Black experience, sort of during, again, the classic period of World War II, what primary sources might you use?

Delmont: Some of the ones that come to mind first are almost bookended. So I think the Thompson letter that I’ve mentioned — and I’ll share all these with Deborah and the Zinn Education Project folks afterwards — but that Thompson letter that launches the Double Victory campaign, because it’s such a powerful rhetorical device — “should I sacrifice my life to live half American?” — that question is just as powerful today as I think it was in 1941.

Then, some of the sources I didn’t know about until I got into the project were the reporting of war correspondents. Not just Langston Hughes for the Baltimore Afro American, but later in the war there were people like Charles Alfred Anderson and “Roi” Ottley [and] Dan Burley who write for Black newspapers; who are embedded with these Black units who are in the Pacific theater and the European theater. Near the end of the war in 1945, they write these really powerful stories that both describe the vital and often unsung work that Black troops are doing to help win the war, but also how those Black troops are already being written out of the history of World War II even as the war is ending. I think that’s the point that really can’t be stated clearly enough — that Black Americans at the time understood what was happening. They understood that they had served a country that didn’t respect their service. They understood that they returned to a country and were discriminated against and were attacked, and in some cases, killed as veterans largely because of their service. They understood that they were being discriminated against by the GI Bill. Those articles are in Black newspapers in 1945, ‘46, ‘47. It’s not just something that historians or sociologists discovered in the last 10 or 15 years. They understand that white historians and other popular media outlets are intentionally writing Black servicemen and women out of the history of World War II.

So just after the war, Life magazine, Colliers magazine published these thick volumes with thousands of pictures from World War II. They include only one image of a Black soldier. This is deeply upsetting to both Black veterans, but also to the Black journalists who covered them, who were on the ground and saw everything that Black troops did to help win the war. And to read these journalists talking about it in 1945, 1946 — as America is celebrating the supposed victory in the war — they’re recognizing that Black Americans aren’t getting their due in helping to earn that victory, but also are already being written out of history. It’s a powerful statement of how history is written and how people were alive to these injustices as they were transpiring.

Theoharis: I want us to talk a tiny bit more about the GI Bill, because I think part of how you’re changing the timeline is not just that people return [from] fighting, right, but that there’s this whole next chapter of both the ways that the war changes life, both for white and Black Americans, and that in many ways, the GI Bill is both arguably one of the most successful pieces of social legislation in the history of this country, and also one of the most discriminatory, or leads to one of the greatest sort of racial gaps. So could you tell us about that? I think we all know what the GI Bill is, but I think if you could kind of flesh that out for us . . .

Delmont: Sure. And in the chat, I dropped a link to an article that came out about a month ago from Mother Jones that draws on some of the material from the book, but actually says a lot more about the GI Bill. I would point people there, as well, to get a fuller view of this. The GI Bill is perhaps one of the most important pieces of legislation in the 20th century. It’s what enabled a whole generation of white veterans to be able to enter the middle class. It provided access to low-interest mortgages that were backed by the VA [Veterans Administration]. It provided access to college tuition, access to job training, small business loans, health benefits, a whole host of resources — to the order of billions and billions of dollars — that helped to essentially reward veterans for their service during the war and help to reintegrate them into American society. And it was wildly successful for white veterans; it’s what enabled them to move into the middle class and then enabled them to accrue resources they could then pass on to their families.

The problem is that as that legislation is being written, some of the key politicians who control these veterans committees were white segregationist senators. It’s important to understand that these politicians were not democratically elected. They came from states where Black people couldn’t really register to vote because of decades of violence and intentional discrimination, things like the poll taxes. But they’re in Washington, D.C. representing states like Mississippi, Georgia, Alabama. And they’ve been in D.C. for a long time, so they have seniority on these committees. What they do when they craft this legislation is they make sure the benefits are going to be distributed at the state level and the local level, rather than at the federal level. If it had been done at the federal level, there’s at least a chance that the government could have enforced some sort of non-discrimination provisions. But everyone at the time understands, if you do things at the state level, that means you’re deferring to whatever policies and prejudices exist at the state level. And again, there’s some that comes through clearly at the time — everyone knows what’s up, so to speak — when you’re talking about the state level.

And that’s what comes to pass, that when Black veterans go to their local veterans branches trying to access these benefits, they’re either given the runaround, they’re denied outright, or they’re pushed into vocational training programs rather than four year colleges or universities. To drill down a bit, at the time thinking about higher education, throughout the South colleges were still entirely segregated. So, despite Black colleges and universities having been incredibly resilient and resourceful, there just aren’t enough seats at these Black colleges and universities to accommodate the thousands and thousands of veterans who want to go to college. So, whereas white veterans are able to use their benefits to go to almost any college in the country, Black veterans are really limited in terms of where they can go, because outside of the South there are quotas that only allow a handful of Black students to go. In the south, the white colleges aren’t allowing any Black students [and] the Black colleges don’t have enough seats to accommodate Black students.

With the mortgage policies, the GI Bill doesn’t require any sort of non-discrimination provisions, which means that it just follows the same racial discrimination that had already been in place in the mortgage and banking industries. So this is a story not just in the South, but in the north as well. In places like New York and New Jersey, Black veterans can’t get mortgages to live in almost any neighborhood. And so by 1950, 98% of those mortgages, these VA-backed mortgages, go to white veterans [and] only 2% to Black veterans. There’s an institute at Brandeis University today that’s done some calculations — these are economists who’ve done calculations on the long-term impacts of this — and what they found is that on average, the benefits that were available to Black veterans were only worth about 40% of the benefits were available to white World War II veterans. And over a lifetime it’s about a $100,000 difference. So when you look at the vast racial wealth gap in the country, and a huge part of that can be traced back to the GI Bill.

The last point I would make is, it’s not the case that no Black veterans were able to get GI Bill benefits. Thousands of veterans were able to benefit from the GI Bill. And what we can learn from that is the veterans who were able to use their GI Bill benefits did amazing, amazing things. They were women like Dovey Johnson Roundtree, who was in the Women’s Army Corps. She uses the GI Bill to go to Howard University Law School and then opens a law firm in Washington, D.C. and wins several important civil rights cases. There was a guy named Robert P. Madison, who fought in the 92nd Infantry Division, [and] earns a Purple Heart for his service in Europe. He comes back, uses [the] GI Bill to earn architectural degrees from Case Western, from Harvard, and then goes back to Cleveland, where he’s from, and opens a trailblazing architectural firm. So part of the story of the GI Bill is that, yes, there’s a huge amount of discrimination that negatively impacted Black veterans, but there’s also what we might call an opportunity cost. That there hadn’t been this discrimination. We can see from the people who benefit from it, that they did amazing things — that if a wider swath of Black veterans had been able to benefit from it, they would have had a whole other generation of Black doctors and engineers and architects and teachers that we didn’t have because of the discrimination.

Theoharis: Also, I think the opportunity gain for white people, I think the ways that the GI Bill makes college much more in the reach of many, many, many more white Americans then it erases the fact that most white Americans didn’t have access to college before 1940. So that opportunity gain, it’s not natural that this happens. Similarly, most white Americans don’t own their own houses before 1940. So that opportunity gain is not just a measure of hard work and the kind of prosperity of the 50s. It’s this incredible leg up, which shows that a leg up works. So this middle class, the kind of prosperity of the 50s is in many ways as much about the GI Bill as anything.

Delmont: Exactly. It’s a massive, massive federal investment that largely benefits white veterans and their families. As you’re saying, it dramatically changes some of the norms in American society — that homeownership was not prevalent prior to World War II; college education was not prevalent prior to World War II, across any race. The fact is, it changed a lot of the norms of what success and middle class status and access to those resources looked like.

Theoharis: You mentioned Roundtree, and one of the other things I think your book does, I think most of the time when we think about the “Greatest Generation,” it’s a picture of men. Right? Or it’s explicitly about women. It’s about Rosie the Riveter, right? And I think your book complicates that — because there are women all over the book. So, maybe you could talk a little bit about how World War II looks for Black women, and from the eyes and experiences of Black women?

Delmont: I think it’s a really important question. In terms of military service, there were thousands of Black women who served in the Women’s Army Corps. A lot of what they described was very similar to what men in the Army, Navy, and Marines described — that they were proud of their service in many ways, but they were discriminated against on these army bases.

There is a story from the Women’s Army Corps in Des Moines, Iowa. One of the troubling things is that not only did the military have segregation on these bases in the South, they also had Jim Crow style segregation on bases outside of the South. So in places like Iowa and California, they transported the norms of the South into these bases elsewhere. One of the things that these women in Iowa described though was that they were only allowed to use a swimming pool one hour a week for recreation, and then they would drain the swimming pool afterwards — just as a petty way to emphasize their second class status. There was a group of Black Women’s Army Corps members at Fort Devens in Massachusetts that staged a protest (and received a court martial) to protest their treatment and their assignment to these menial positions at Fort Devens.

But the largest group who goes overseas, there’s a group called the 6888th Postal Directory Battalion, who’s under the leadership of Major Charity Adams [Earley]. They’re the ones who are responsible for delivering mail all over the European theater. Which is actually a really complicated job, because you had all these guys named Tom Jones and John Smith and they’re in units that are moving constantly. But they developed systems to distribute the mail, which both Black and white troops after the war say was really essential to morale. So this Postal Battalion is among the Black women who were in the service and who deployed, was among the most important who were deployed. On the homefront, there are more than a million Black Americans who work in the defense industries and 600,000 of those are Black women. And those were really important factory jobs and important employment opportunities, because primarily, before the war, the main work opportunities outside the home for Black women were either in agriculture or working in domestic service for white families. One of the consistent refrains for these Black Rosie the Riveters was that it was the war that helped to get them out of white women’s kitchens. It opened up new employment opportunities for them during the war. It was also the case that they were deeply involved in protests. Whether it was with the NAACP or the March on Washington movement, Black women were key organizers and key participants in the civil rights protests, including getting access to a lot of these defense industry jobs.

The last piece that I think comes through clearly when you read a lot of the stories, particularly in Black newspapers from the time, that, as with any community where you have to send people off to war, the loss of people in those wars had serious impacts on communities and on family members. So, for the women who had brothers go to war, fathers go to war, husbands go to war, those stories, those memories came through really powerfully in Black newspapers at the time, and then in their recollections afterwards. So throughout the book, as you’re talking about the history of World War II it’s very easy to overemphasize the male aspect, particularly on the military side, I tried to make clear throughout that you cannot understand this history without understanding the really vital roles Black women played both on the home front end and on the war front.

Theoharis: So we don’t have too much time left. And people, if you have to leave, I think Aileen has put in the chat the link to do the survey and to request if you need PD certification, or if you want a free copy. But I guess where I want to end this conversation is actually not with this book. Because this is the Teach the Black Freedom Struggle series, one of my all time favorite Black Freedom Struggle books is Matt’s earlier book Why Busing Failed. Because we haven’t had you here to talk about that book, I kind of wanted to end there just to give people a tiny taste of what that book does. One of the things I love about the book is that you got your publisher to let you put “busing” in quotes for the whole book. So why did you do this and what are you trying to get us to see about this false frame of busing? Just to give us a taste of this book, so people can get that book, too.

Delmont: Thank you. I dropped in the chat the companion website for Why Busing Failed. For all my projects, I’ve tried to create web resources. So if you go to that website, it’s open access, you’ll find a lot of the primary sources and essentially like a Reader’s Digest version of the argument for the book, designed with teaching in mind.

So in Why Busing Failed, the reason I asked the publisher and put “busing” in quotes throughout the book was that the framing of how we talk about school desegregation really matters. One of the arguments I make in the book is that the people who were opposed to school desegregation, who wanted to maintain school segregation across the country, were really successful in framing the terms of the debate. That idea of busing — the way it emerged is a term of protests in the 1960s and 70s — that was a choice. It was a choice that the media made in terms of how to report on this. It was a choice that protesters made in terms of how to protest against what they saw as an unfair disruption to school segregation. It was a choice that judges and other political officials made to use that term as a way to understand school segregation. Those debates over busing were fundamentally about the constitutional rights of Black students and Latino students in terms of having access to equal education.

But once that history and those events got linked to this term “busing” it became a conversation about the anger and frustration of white parents. And I think that’s a really important historical point to make — that if we talk about busing and only focus on the perspective of the “anti-busing” protesters, that means you’re only focusing on the anger of white parents and protesters. You’re not focusing on the history of the Black students, the Puerto Rican students, the Latino students, who were trying to get equal education in these schools in the north, particularly in Pontiac, in Chicago, in Boston, in New York.

Jeanne, we’ve had a chance to write on this history together, but it matters deeply. I mean, one of the most surprising things for me as a historian is that the Smithsonian at one point asked me to write a blog post about some of the materials they had about the Boston busing crisis. And I said “Sure, I’d be happy to do it.” When they sent me what they had, though, everything they had was from the anti-busing protesters, this group called ROAR, Restore Our Alienated Rights, which were white protesters who were protesting efforts to desegregate Boston schools after more than a decade of protests by Black activists. They had nothing from activists like Ruth Batson or Ellen Jackson, who’d been fighting for more than a decade to integrate these schools.

For all of us as educators, that should make us aware that — particularly when we talk about the history of civil rights in the north — there’s a tendency to focus on white people as opposed to Black students at the center of the story. If you think about what it would mean to talk about the history of Little Rock, but not talking about the Little Rock Nine or talking about Daisy Bates, but talking about the white mobs as the center of the story, that’s a very distorted history. We would know that was wrong when it’s happening with Little Rock, but for some reason we’ve accepted that way of framing the story when it comes to Boston. So, part of what the book tries to do is, again, change the timeframe of the story — I start in New York in the 1950s, recognizing people were fighting about this for decades — and then try to give us an understanding of how media shaped and distorted this history.

Theoharis: From the chat, we can see that people want you back so we can have a longer conversation about it. Because there’s so many things that — I think, for those of us who are teaching about this history — we need to know. I mean, for me, one of the biggest revelations when I started to look at Boston, and we talked about this for years, is that most of the students in Boston are being bused before busing. So we have to put it in quotes because it’s like, “Well, they are being bused. But busing is a whole different concept.”

So I just wanted to say two things. One, for everyone on the call, we are back next month, and next month Bryan Stevenson is joining us. Then we have a whole roster in the spring. We just put a link in the chat so you can see where we’re going. But again, the Teach the Black Freedom [Struggle] series is once a month on Monday nights. We’ve got a lot to look forward to, so please look at the list. And come again, and again and again.

I think I wanted to end just by saying both thank you to Matt and this wonderful conversation and making this book available and all of these resources. Again, one of the things I admire about you is how much you think about teachers and how much you make your books usable for us as educators. This is yet another way that you’re doing that. Finally, thank you to everyone. Again, this is a hard time of the year, and an incredibly hard moment to be teachers, so thank you for just continuing to join us in this community. I love the chat, I always love the chat on these Zinn [Education Project] evenings. So thank you, be safe, please remember to fill out the evaluation. And again, if you want the book and if you need PD certification, please let us know. Have a wonderful evening. Thank you so much.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Audiogram

This two-minute audio excerpt describes the connections between the struggle for Black liberation at home and the fight against fascism abroad during the 1930s and 1940s.

Resources

Here are many of the lessons, books, articles, and more recommended by the presenters and also by participants.

Lessons

|

How Red Lines Built White Wealth: A Lesson on Housing Segregation in the 20th Century by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (lesson) The Other Internment: Teaching the Hidden Story of Japanese Latin Americans During WWII by Moé Yonamine (lesson) Repair: Students Design a Reparations Bill by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (lesson) |

Books

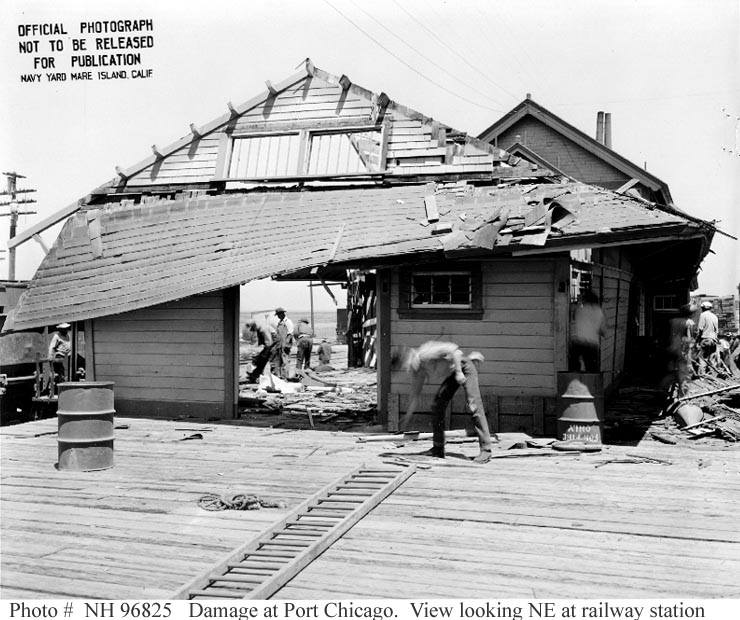

| In addition to Matt Delmont’s Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad, the following books were referenced: Mighty Justice (Young Readers’ Edition): The Untold Story of Civil Rights Trailblazer Dovey Johnson Roundtree by Katie McCabe and Jabari Asim (Roaring Brook Press) The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America by Richard Rothstein (Liveright) Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision by Barbara Ransby (University of North Carolina Press) The Lincoln Brigade: A Picture History by William Loren Katz and Marc Crawford (Wipf and Stock) The Port Chicago 50: Disaster, Mutiny, and the Fight for Civil Rights by Steve Sheinkin (Roaring Brook Press) |

Articles and Resources

|

Black Quotidian by Matthew Delmont “How a Hostile America Undermined Its Black World War II Veterans” by Matthew Delmont (an article in Mother Jones) “The Forgotten Fight Against Fascism” by William Loren Katz (from the If We Knew Our History series) The Black Press: Soldiers Without Swords a film by Stanley Nelson History Unfolded, U.S. Newspapers, and the Holocaust (an interactive database and archive of WWII Black journalism) “Will V-Day Be Me-Day Too?” a poem by Langston Hughes |

This Day In History

|

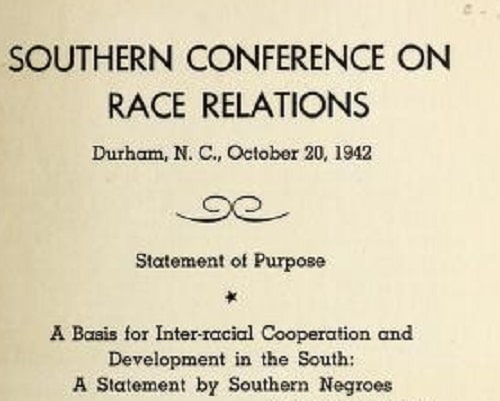

April 2, 1917: Jeannette Rankin Takes Seat in Congress Oct. 3, 1935: Ethiopia Invaded by Italy Oct. 20, 1942: Durham Manifesto June 22, 1944: GI Bill Signed July 17, 1944: Port Chicago Disaster and Mutiny July 18, 1946: Murder of Maceo Snipes Nov. 11: Veterans Day |

Participant Reflections

Nearly 50% of participants were K–12 teachers, though numerous teacher educators, librarians, and historians joined in, too. Here are more comments that participants shared in their end of session evaluation.

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

How the GI Bill left so many Black veterans out and how the country could have had thousands more Black professionals if they had been given the same benefits as white veterans.

I am becoming more and more sensitive to how overwhelming this history is for students. Providing this history is a gift, yet it can hold painful truths. My challenge is to help them discover it at their own pace and with compassion and empathy for their frustration.

As a literature teacher, I know Delmont’s discussion of challenging the master narratives of the “Greatest Generation” and national sacrifice helps put the time period in better context for my classes.

The way the Black press covered the rise of fascism in Europe was fascinating.

I learned the irony and hypocrisy of how African Americans fought abroad for WWII and faced such discrimination and violence back home. How more effective the U.S. would have been to end the war if they had not segregated their Black soldiers.

It was fabulous to hear the conversation between Dr. Theoharis and Dr. Delmont. Their friendship and history of working together really came through in the clarity and depth of this conversation. Jeanne’s questions were great, modeling how historians ask questions. Delmont’s responses were connected and clear. Powerful and easy to understand.

Thanks so much to Dr. Delmont. This was a very clear, interesting, and engaging discussion. I see his dedication to putting this history into the world so that it can get to work in changing our understanding of today. He is putting the history to work by creating these resources for educators.

What will you do with what you learned?

It will make teaching the Civil Rights Movement deeper, which will bring more context to the Black Lives Matter movement.

I am going to teach perception through the media. I will choose different articles from various media and have students discuss what they notice.

Look beyond the surface of people and their stories — how are they connected to other people, other ideas, movements? Is the story I’ve been hearing (for however many years) accurate?

I am not a teacher, but there are opportunities to discuss these things at the dinner table.

I will integrate as much as possible in my own programs and also share with others in my T4BL study group.

I will now use WWII in teaching U.S. history as a means to explore the early movement infrastructure that would later be used by the Civil Rights Movement. I’ll also highlight how the Black press provided more moral clarity in their coverage of WWII.

I plan to take this general idea/lesson and bring it into my own classroom. I teach early American history and many of these same lessons/ideas parallel the history that I teach my students. I also have been inspired to bring into my classroom more experiences of everyday individuals who might otherwise be overlooked in history classes — to show students that behind each huge moment in history are regular individuals, such as themselves.

Presenters

Matthew Delmont is the Sherman Fairchild Distinguished Professor of History at Dartmouth College. A Guggenheim Fellow and expert on African American history and the history of civil rights. He is the author of five books: Half American, Black Quotidian, Why Busing Failed, Making Roots, and The Nicest Kids in Town. His work has also appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, the Washington Post, NPR, and several academic journals.

Jeanne Theoharis is a distinguished professor at Brooklyn College. She is the author or co-author of nine books and numerous articles on the Civil Rights and Black Power movements and the politics of race and education. Her books include the award-winning titles The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks and A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn