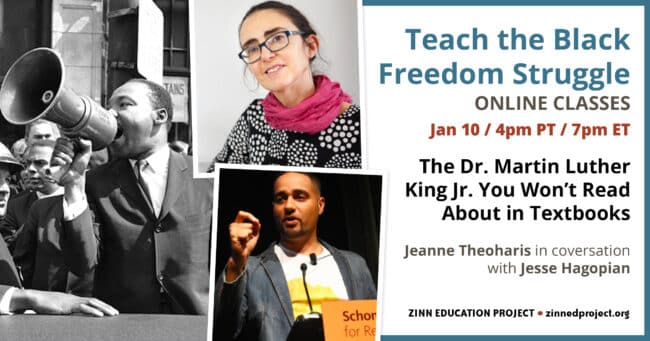

On January 10, the Zinn Education Project hosted historian Jeanne Theoharis in conversation with Jesse Hagopian about the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. that is not found in textbooks and school curricula. This was for the Teach the Black Freedom Struggle series of classes with people’s historians.

As Theoharis notes in an article in The Atlantic, “Critics of Black Lives Matter have held up King as a foil to the movement’s criticisms of law enforcement, but those are views that King himself shared. Martin Luther King Jr. proclaimed, ‘We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality.’ King understood that police brutality — like segregation — wasn’t just a southern problem.”

Here are a few reactions from participants:

My instruction is now more informed with truth and I am able to provide a broader context for his work.

Dr. Theoharis’ scholarship helps me understand civil rights history in a way that I was never taught. Thank you.

I learned that Dr. King’s public persona was definitely white-washed to make him more acceptable to the white audience and less intimidating, as well.

Jeanne Theoharis had the presence of mind to ground us in the difficulties of the struggle today for educators. Jesse Hagopian followed suit and signified how hard the work is at this moment in these grim conditions.

Thanks so much. This community means a great deal to me. The ideas embolden my political imagination and offer succor. I also just love seeing people who are in the struggle for radical education.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: We are very fortunate this evening to be joined by Jeanne Theoharis, a distinguished professor of political science at Brooklyn College. She is the author and editor of numerous books, including some of my favorites: A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History and also The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks and the new YA edition, which I highly recommend educators get for their classrooms. She is also the co-founder and collaborator on this series and is a true people’s historian in her scholarship and her practice. So, welcome Jeanne.

Jeanne Theoharis: Thank you. It’s so great to be here. But, I do feel like we need to have a moment; like what a hard week it’s been, a crushing week I think particularly for educators. So, I just wanted to hold space for a second just to say I know it’s so hard and if you’re feeling like it’s hard please understand you’re in community together with us tonight. Because we think we’ve seen the most disrespectful thing and then we see something else even more disrespectful, and

Hagopian: I know the attacks keep coming on hard-working educators and it seems like our health and safety is not the priority for these school systems and for the broader country, so it helps to all be in it together though and have some comrades in the struggle. So I’m glad people have joined us in this community.

Thank you for starting us with that acknowledgement, and I’m really excited about this class today, because we really have to win back the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. We’re in a struggle for his legacy right now and because everybody seems to want to claim him — I mean you have the left claiming him, liberals claim him. I remember seeing a McDonald’s ad growing up that celebrated Martin Luther King at the same time they’re not paying a living wage to their workers.

Then, today you have even the far right anti-Critical Race Theorists — I like to call them uncritical race theorists — they claim him, as well. In launching the anti-history 1776 Project, President Trump even said quote “there’s no more powerful force than a parent’s love for their children.” And patriotic moms and dads are going to demand that their children are no longer fed hateful lies about this country. We embrace the vision of Martin Luther kKing where children are not judged “by the color of their skin but the content of their character.”

This quote from King is repeated ad nauseam and I wanted to ask you why is Martin Luther King claimed by people with such different politics? I’m also curious to know what you think King would say about the struggle over Critical Race Theory today and what King would want students to learn about in school today.

Theoharis: Well, to start off I think we want to remember that this kind of sea change is not true when he dies. Somewhere between two thirds and three quarters of Americans don’t approve of King, don’t approve of his work, when he dies. And we’re going to see that flip twenty years later.

For people who are interested, I talk about this in A More Beautiful and Terrible History, that part of what we see, from the very beginning we see this push for a King holiday by civil rights activist Coretta and there’s all this pushback. Then we get to the 1980s and President Reagan had been a longtime opponent of the holiday but he’s running for re-election and he starts to see it as a way to win over moderates. So interestingly, that opposition changes to support and we see Reagan sign the federal legislation making the third Monday of January a holiday for Dr. King. I think that’s a really important moment because I think if we look at what Reagan says that day — he puts forth this kind of American exceptionalist idea of King that I think then lies at the heart of the way that everybody feels. Like [they] would be friends with King, they’d be protesting with King, and that’s this idea that in most countries Dr. King wouldn’t even get to speak at all, but in a country like the United States, when you shine a light on injustice, and you do it the right way, then it changes. And King and Parks are kind of the poster children for this idea. So what I think then happens is that King becomes a way to celebrate the robustness of American democracy, and then everyone claims him because he seems to stand for American progress.

I think one of the most misused quotes of King is “the arc of the universe is long but it bends towards justice,” because I think that tends to be used in this narrative of progress, that we might still have a long way to go but we’re just constantly progressing. And King himself took that, too. I mean King eviscerated this idea, he called it the myth of time. It’s like time is neutral basically, and I’m paraphrasing him, the forces of evil have used it better and that there’s nothing, like things only progress through our actions and this notion that America’s gradually progressing towards more and more justice is not true. So, in many ways I think there’s this way we hold on to that quote because I think it gives us hope in hard times and I think there is a way that obviously King is a religious man and he’s talking about the god of justice, but not the way that we tend to misuse that quote, which is like this narrative of just constantly getting better and better, which is I think one of the key ways that King then gets used by both conservatives and liberals to basically be like ‘we had a problem and we’ve largely fixed it and yeah America.’

Hagopian: Yeah, absolutely. It seems to me that that’s just such a great framework for how we got to this situation where everybody claims them, and most people really misuse his legacy and it just is galling to see how many times the right use a couple of quotes out of context to attack Critical Race Theory in schools. They’re gearing up right now to celebrate MLK day as a way to attack kids’ rights to learn about structural racism.

Theoharis: One of the things I think we’re going to talk about today, and kind of is the heart of why we decided to have this session, is the new book that I’m working on which is really looking at Dr. King’s long-standing understanding of northern racism, or racism as not a southern problem but an American cancer, and therefore his understanding from the 1950s onward — not just in 1967 — of structural racism in this country, that racism is not about hate or meanness. I mean, again, I think some of King’s quotes about love tend to get misused to obscure how he understands racism fundamentally as structural and the ways that he also understands that the south is often used to shield northern liberals. And by north I mean what King would mean would be northeast, midwest, and west coast from grappling with the racism endemic in those places.

Part of what we’re going to be talking about tonight is all of this, this is what my research has gone and just really uncovering, this whole other side of King that I think we’re so much less familiar with, and how long he called out northern liberals, how long he stood with northern movements. I think we tend to see King only taking on northern racism in the last years, post-Watts, and that’s just not the case. So, we can talk about that and I can share some resources on that. Because in some sense, even as much as I think we all have tried to get outside of the myths of King, one of the things that I’ve been really grappling with in this new project is how much there’s still ways that we tend to buy into things about King, like King being this southern respectability politics guy when over and over and over he’s calling out these kind of behavioral solutions as not solutions; that personal responsibility is not public policy and what you need is public policy and calling out the police and the courts and seeing the situation in northern cities as a system of internal colonialism and seeing racism as being about profit and materialism. This is the King that I think we want to sit with and learn more with, because I think he really speaks to where we are today.

Hagopian: Yeah, absolutely, and I hope that so many teachers will be emboldened after our session today to lean into teaching about structural racism and know that King would have your back in that struggle. I can’t wait to dig into more of what he thought about some of the other struggles in the north, for sure. But, I want to also take a look at some of his views on what he would think about Black Lives Matter and police. In some of these, the call to defund the police, I think, has really captured people’s imagination.

In this wonderful book, A More Beautiful and Terrible History, you quote King saying,

When we ask Negros to abide by the law, let us also demand that the white man abide by the law. In the ghettos, day in and day out, he violates welfare laws to deprive the poor of their meager allotments. He flagrantly violates building codes and regulations. His police make a mockery of the law, and he violates law on equal employment and education and the provisions for civil service.

So, give us context for that quote and what King’s attitude would be to the police and systemic racism.

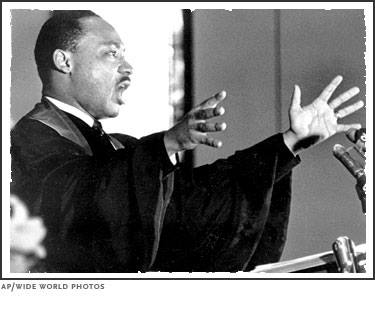

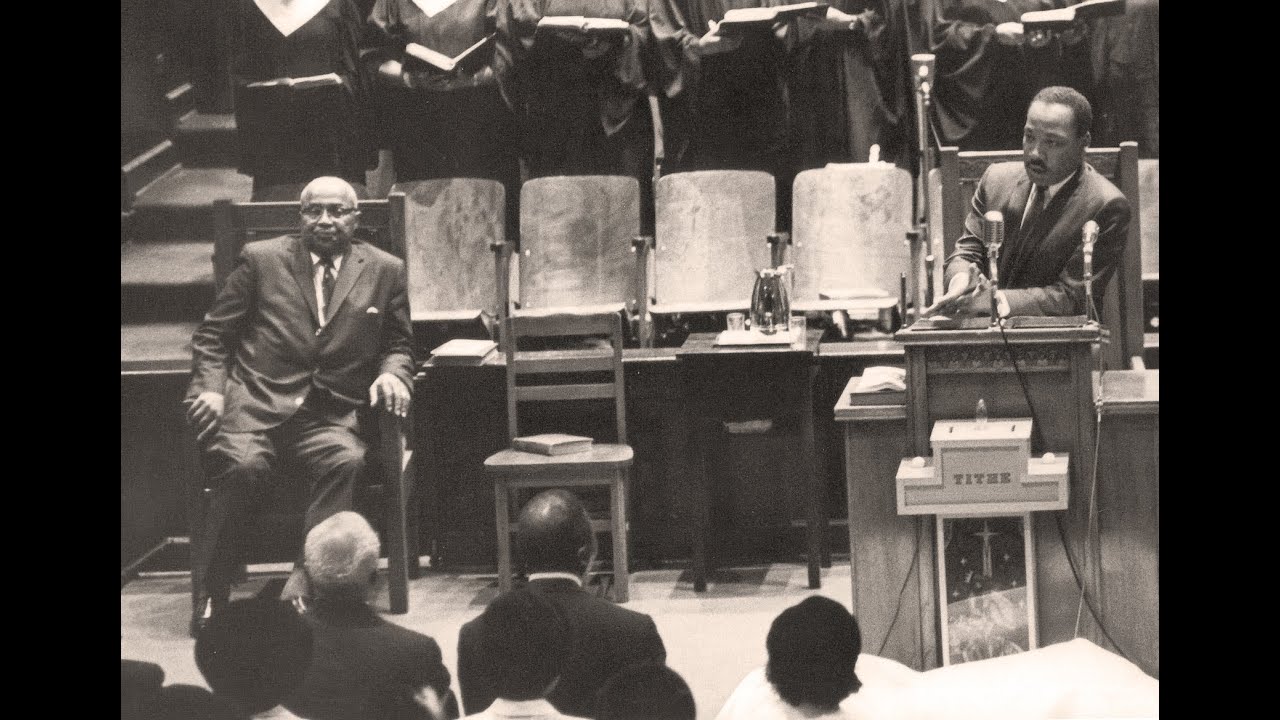

Theoharis: There are a couple of things just to really remember from the outset. The first is that King has a lot of experience with police abuse and police misconduct. King was arrested 29 times and he is often roughed up in those, and some of them are caught on tape. So, if you’ve ever seen, in 1958 Ralph Abernathy is on trial for something, and he and Coretta go down to the courthouse in Montgomery to try to go see him, and they arrest him for loitering. Then there’s a very famous picture where he’s basically [in a] half -Nelson, they pinned his arm behind his back and they have his head down on the counter — and this is in front of a photographer! Then they arrest him and they take him back to the cell and they rough him up in the cell. You may also have seen when he gets arrested in April of 1963, where he goes to Birmingham, when he’s getting arrested they lift him off the ground.

So, I think one of the things that I’ve done more lately is to go back to things we think we know and to watch them again. It means that to have the police pick your body up, King was terrified of the police and I think we forget what it takes to get arrested time after time after time. In fact, I should say, the first time he’s in Montgomery is during the Montgomery Bus Boycott. He gets arrested for speeding five miles over the limit and then they take him into their car, they don’t just give him a ticket, they drive him around — he thinks he’s going to be killed. So, from that very first counter, he’s terrified of the police. What it takes for King to be able to do this over and over and over, I think we sometimes forget that. So, that’s the first thing I want to bring up.

The second thing is, I think sometimes we tend to think about King’s critique of the police being about southern racist police. Part of why Jesse just read that quote, and why I think it’s so important, is because he’s talking not just about the police as bad individuals but a structure. So when he talks about this system of internal colonialism in northern cities he calls the police and the courts enforcers of that system. He talks about the ways that police abuse . . . After the Watts uprising he writes this piece where he’s talking about how disillusioned he is because he’s often welcomed in these northern cities, but the minute he starts talking about northern injustice then “only the language is polite” is what he said.

Then he writes, “ As the nation Negro and white trembled with outrage at police brutality in the south. Police misconduct in the north was rationalized, tolerated, and usually decided.” In fact he had been calling for change in the police. A year before the Watts uprising there was a six-day uprising in Harlem and the mayor invited King to the city to try to calm things down. King gets to the city and basically he’s like, “You need a civilian complaint review board. You need to basically fire the cops.” And the mayor totally ignores him. But this notion that King is separate from the calls that we are talking about today just is not borne out when you actually look at what King is doing and how he talks about the police.

Let me read you one more thing, and this is from 1964; this is not 1967 King, this is 1964.

Armies of officials are clothed in uniform and vested with authority, armed with the instruments of violence and death, and conditioned to believe that they can intimidate, maim, or kill Negroes with the same recklessness that once motivated the slave owner.

Wow. I mean, he’s very much thinking about the role that the police play, not just racist Bull Connor or racist Jim Clark, but the role the police play in society. So, I think that’s really important.

The second thing I want us to think about in terms of Black Lives Matter, I think we often forget that at the heart of King’s belief in nonviolent direct action is a belief in disruption and the need for disruption. I think we’ve made him into passive [and] hand-holding and he’s [actually] very clear that in some sense part of what nonviolent direct action is supposed to do is it’s supposed to upset; in some sense injustice is comfortable.

Just to give you one one of my favorite examples, because it is such a direct parallel to today. In 1964, Brooklyn CORE, the chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality, had been organizing for years. They’d been organizing around housing segregation, around job discrimination, around school desegregation. They’ve managed to win two jobs at [illegible] Bakery and they managed to get one family into a different school. So, all these token things, and by 1964 they are really fed up, and 1964 is the year of the World’s Fair here in New York City. So, Brooklyn CORE decides that they’re going to escalate their tactics and they are going to call for a stall on the highway going out to Flushing Meadows, which is where the World’s Fair is going to be held. Now, this obviously sounds familiar; people go nuts, I mean white leaders and Black moderate leaders, Robert Moses of New York, they all think it’s a horrible idea, terrible, and they try to get King to come out against this idea, and King refuses.

I’m just going to read you what he writes:

We do not need allies who are more devoted to order than to justice.

And again, this is calling for a highway stalling. I hear a lot of talk these days about how King writes about how our direct action talk alienates former friends.

I would rather feel they’re bringing to the surface latent prejudices that are already there. If our direct action programs alienate our friends they never were really our friends.

I mean, I can give you lots of other examples, but I think at the base of those examples is his understanding that nonviolent direct action has to be disruptive, it has to make people uncomfortable. It’s not about making people love you, it’s about making people uncomfortable enough to be changed and moved to action. It’s not about one big group hug, and that’s how you get changed. No. So, I think that’s the other way that I think he’s really misused, because I think there’s often this sense with Black Lives Matter of ‘you’re not doing it the right way, you’re not using the right tactics,’ when in fact most of the criticisms of Black Lives Matter are criticisms that were waged against King and the Civil Rights Movement for being reckless, for being out of control, for being aggressive, for being disruptive. All of those things are waged against King as well, even though that’s not how we remember.

Hagopian: That’s right. There is so much there. Thank you. What I just took away from what you said that I hadn’t fully processed was the radical ideas that King had early on. I guess I had also thought about him coming to radical conclusions. Certainly in the last year of his life all sorts of radical statements are being made. But you digging up that quote from 1964 really just puts lie to everybody trying to use him to moderate the struggle today.

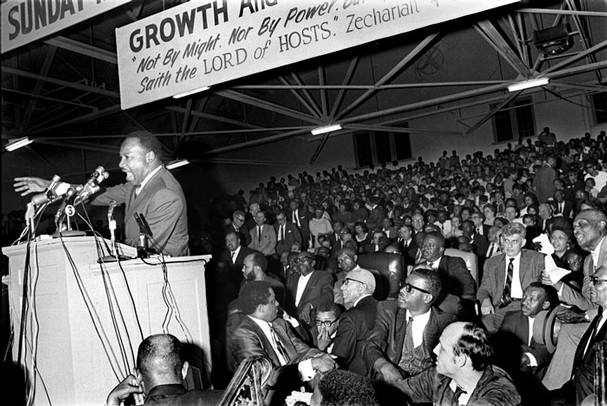

Theoharis: Totally. I mean, let me give you one more example, just because we’re on the topic of schools. So, one of the tactics that northern movements start to use by the early 1960s, because they’re trying to get desegregation in New York, in Chicago, in Boston, and they’re getting all this resistance — “We don’t have segregation here,” “We don’t even keep track of it,” “This would require busing [and] we don’t like busing” — and so one of the tactics you see northern movements turning to by 1963, 1964 is the school boycott. In the fall of 1963 in Chicago the biggest civil rights protest — we’ve talked about this in these sessions before — happened. Not the March on Washington, but it happened in New York City in February 1964 where almost a half a million students and teachers stayed out of school to protest the fact that they were ten years after Brown and there was still not even a comprehensive plan for desegregation in New York City, let alone actual desegregation. So again, King was supporting the school boycott in Chicago, supporting the school boycott in New York, and supporting the school boycott in Boston. And there’s all these critics in the New York Times, they hate this, and so two months later King, in a column in the Amsterdam News, comes out again in favor of the school boycott and really is taking some of these critics on.

“The school boycott in practice has proved very effective,” he writes, “in uncovering the injustice and indignity that school children in the Negro, Puerto Rican minority communities face. School boycotts have punctured the thin veneer of the north’s racial self-righteousness.” This is the spring of 1964, pre-passage of the Civil Rights Act. “School boycotts have punctured the thin veneer of the north’s racial self-righteousness.” Responding to the criticism that these disruptive tactics alienate well-meaning allies, King made clear the truth of the matter is that it is the harvest of past apathy to tragic conditions that were allowed to exist without any serious concern. Basically he’s like “this has been happening and you’re getting all upset with this tactic and the reason you are is because you have let this problem go on.”

Hagopian: Wow, brilliant analysis and also beautiful language. I thank you for sharing his direct quotes there. I love the way he condemns the northern structural racism in the schools. King is widely celebrated but only a very narrow part of what he said is lifted up in the mainstream, like four words from his speech at the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom are often repeated. “I have a dream.” But not his more radical views, such as when he said “something is wrong with capitalism, there must be a better distribution of wealth,” and “maybe America must move towards democratic socialism.” So, I’m hoping you could talk about his economic vision, his views on unions and class.

Theoharis: I think we want to go back to the March on Washington speech, where it begins with him talking about America giving Black people a bad check. Again, many of us might not use checks anymore, but he’s saying basically they’ve come there, they refuse to believe, and again iI’m paraphrasing him, that they’ve defaulted on this promissory note, but they’ve come to collect. What we know about a bad check is that the only way to write a bad check is you have to have a good check; you don’t get to just apologize and say, “So, I gave you a bad check. I didn’t mean it.” You have to give people a good check; so to me, in that most iconic speech, King is saying “we are here for material redress. That’s what it’s going to take.”

I think that’s the fundamental idea, but when we talk about that in terms of Reparations we could talk about the harm being not just a moral harm but an economic exploitation. Certainly he understood segregation to be, again in the way that we tended to see his critique of segregation being about meanness or about people not wanting to sit next to each other, and he very much talks about it in terms of profit, in terms of how much money is being made and also taken out of the Black community. And I think we miss what we might call the racial capitalism argument that King is making. So he understands and, yes, so he’s assassinated.

He’s building a Poor People’s Campaign. One of the last things he’s working on at the end is bringing together . . . he’s talking about the three evils of poverty, racism, and militarism, and he’s building an interracial Poor People’s Campaign when he’s assassinated. That will be continued by his friends and colleagues that summer, and again the vision, and then its continuing in a new version, a new Poor People’s Campaign today that’s being co-chaired actually by my sister and Reverend Barber. So yes, this vision was where he was at the end of his life, that we need to attack these three things in tandem, and that you can’t not talk about militarism because, in fact, this is the constant argument used to say “we can’t pay for these other things.” So King is talking about how that becomes a way to also deform and distort our society.

Hagopian: Totally, and I love that there’s a new Poor People’s Campaign. That’s really the way to honor mMartin Luther King today. If you want to check out that campaign and get active in that, not this nonsense from the right.

I want to ask you one more question before we move to the breakout sessions and that is more about your new book that you’re working on now. The Civil Rights Movement is generally taught as a southern phenomenon and yet, as you pointed out earlier, some of the biggest protests of that era were actually in the north. In your new book on King, you’re focusing on Martin Luther King’s work in the north, so I’m hoping you can speak about what that work looked like and what he thought about northern liberals.

Theoharis: I came to this work, well, it started a while ago. I was [doing] research on the Civil Rights Movement in LA, pre the Watts uprising and I kept finding Dr. King and I was like, “Wait a minute, this is not the story I was taught.” The story I was taught was that King turns his attention to LA and problems after Watts, and King is in LA at least 15 times in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and he’s standing with movements around school segregation, he’s standing with movements against police brutality, he’s standing with movements fighting housing segregation. It’s not like he’s just there raising money for the south.

So that’s where this journey began, and I just realizing how much this argument then makes King, it distances us from him, because I think that one of the ways, if you are forced to see that King actually sees racism structurally, he sees that it’s not a southern aberration but fundamental to the nation. He’s constantly, from the beginning, critiquing northern liberals who point to Mississippi but aren’t dealing with job discrimination or housing segregation in their own community, and he’s constantly talking about that. One of the things I realized that I hadn’t paid attention to is that King actually spends these formative years of young adulthood in the north.

We know his biography: he goes to Morehouse early, he starts at Morehouse when he’s 16, so he graduates Morehouse at 19. It’s at Morehouse that he gets his religious calling; he didn’t necessarily think he wanted to follow in his father’s footsteps because he found it too emotional and not tied to the world. And then he found a path, a religious calling, that was where he could blend those two. He decides to go to divinity school and he goes to divinity school at Crozer Seminary in Pennsylvania [where] he spends three years and then he goes on to get his doctorate at Boston University. So he basically spends from age 19 to 25 in the north confronting not just a promised land but also the racism of the north.

For instance, when King moves to Boston he’s 21 or 22, and he has huge trouble finding anybody who’ll rent to him. He talks about the incredible housing segregation that he counters there. A year before, in 1950, he and some friends went out for drinks across the border from where he’s in seminary in Maple Shade, New Jersey. The owner refuses to serve them, they protest, they say, “Hey, New Jersey has an anti-discrimination law.” The owner gets a gun and basically threatens them at gunpoint and kicks them out. They’re outraged. They go back, they think about [suing] because New Jersey has an anti-discrimination law on the books. These three white University of Pennsylvania law students offer to help because they go and test the place they’re served. But then when push comes to shove, those white University of Pennsylvania students back out, so they won’t testify and the case falls apart.

So, King’s own personal experiences — and I could go on in the north — are both showing him the racism of the north, but they’re also showing him the limits of northern liberalism, the limits of anti-discrimination law, the limits of people who say that they’re your allies. Allies kind of get flat, flabby, and so to me part of our story begins there, so that when he moves from Boston [and] takes his first job in Montgomery, that’s when we meet him and that’s when he starts to step into this leadership role. But he comes to that with six years of becoming an adult, becoming who he is as an intellectual, who he is as a religious leader in the north. There is never a moment when King is not writing about it.

Also, the north is in his first book on Montgomery, Stride Toward Freedom, he is also calling out northern liberals and the need for northern liberals to be liberal at home and not just look at the south. That is there from the very beginning. I think just seeing that coming out of King’s own experience [and] also in the ways that we tend to see that experience and miss its import I think is really significant.

Hagopian: Yes, that’s so useful. One question for you, Jeanne, could you talk more about how King developed his radical ideas about racial capitalism, about the police, about imperialism, about Black liberation? Who were his mentors, his teachers, his experiences that led him to those conclusions?

Theoharis: A couple of things. I think we want to remember how young King is in Montgomery. He is still in formation, he is 26 years old that morning, December 2, when he gets the call from E. D. Nixon that the Women’s Political Council is planning a boycott for Monday and they’re trying to get the ministers on board. They want to use King’s church. If anybody’s ever been to Montgomery, King’s church, the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, is really centrally located in Montgomery. It’s right next to the capitol. They want to use King’s church for this meeting to get the ministers on board and King basically says that morning — and the King’s have a three week old baby, their first baby. They’ve just had her — and he hesitates and he says, “Can you call me back?” Just like any of the rest of us would at 6am. I always like to start there because I think we sometimes assume that King just knows what to do, or he’s just destined or whatever.

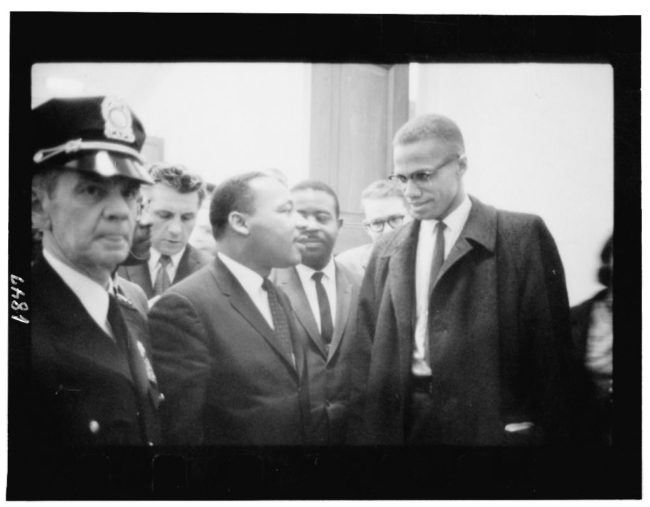

And I think that Jesse’s question about learning takes us in a different direction, which is that King is in process and he’s going to have to make decisions, and he’s going to have to step into this role. Part of how he steps into this role is by one of the things that I’ve come to see again in research for this new book is that he’s doing all of this traveling, he’s speaking all over the country, but in doing so he’s also hooking up with all of these different local movements in all these places and learning from that. And one of the people he’s learning from is Bayard Rustin. People might know Rustin as one of the key organizers of the 1963 March on Washington. Rustin is a socialist, he’s a journalist, he’s a pacifist, and he’s one of King’s key interlocutors, from the Montgomery Bus Boycott until 1960.

And then Adam Clayton Powell. People may know that Adam Clayton Powell doesn’t like that King is learning from Rustin, and King and Rustin in some sense embody a different kind of masculinity than Powell. It’s nonviolent but confrontational, and Powell is a politician, a backroom dealer. So he doesn’t like how much influence Rustin has in terms of the ways that King is turning into a leader. Again, this is a much different kind of “race man,” if we’re going to use that term. People may know that Powell threatened to say that Rustin and King were having an affair, and even though they’re not having an affair King can get scared, Rustin offers to pull back, and King takes him up on it. So, for a while then King and Rustin’s relationship fades. Then we see that it grows again around the March on Washington, and he will be very important in terms of King’s thinking in 1964 and 1965. Then again, they part ways because Rustin gets more pragmatic and King gets more radical. So, Rustin is a key person who’s shaping King’s ideas.

Another thing I want us to be thinking about is just how it’s shaping King’s ideas to be traveling around the country seeing all these different movements, and in some sense growing from that knowledge, seeing what people are trying, seeing what’s working and not, but also seeing in many ways particularly how much resistance there is in the north that looks different than the south. It’s not necessarily the klan, it’s not necessarily burning crosses. Sometimes it’s violent, sometimes it’s bureaucratic, sometimes it’s using the levers of power. But to think about King always learning, and to think about King as an intellectual whose journey . . . I mean basically he’s 26 when it starts and he’s 39 when he’s assassinated. So, he’s learning and in some sense part of King’s genius is his ability to constantly keep thinking things over and turning things over and reshaping things. I think we miss that aspect of King. King is a dynamic thinker and political strategist or activist.

Hagopian: Yeah, I love that description of how he was constantly in motion with his ideas and learning, developing, rather than the image that often gets portrayed of a fully formed messiah. Some of my favorite artists, too, never got stuck in one period. I love how Miles Davis freaked everybody out with fusion jazz, or Bob Dylan freaked out his audience, too. We change and develop and grow, and I really like that description.

We have some really good questions coming in the chat that we can move to. Somebody asked why is the narrative that Dr. King’s radicalism was gradual and post-Watts?

Theoharis: I think part of this is the media and thinking about the role of the media in the Civil Rights Movement. Again, we have a too simplistic narrative because I think the media plays a very important role in shining a light on the Southern Civil Rights Movement. John Lewis will talk about the role of the media like we would have been a bird without wings, and certainly there are some really key moments, particularly if we think about the Freedom Rides or the sit-ins or what happened on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. The media then shines a light on those things in a sustained way that then begins to change the United States, but that same media is based in the north and tends to take a very different tone when covering civil rights issues at home.

This is another thing that I’ve gotten very interested in in this new project, the ways that I’ve been looking for instance at the ways the New York Times covers the movement in Birmingham in 1963 versus the ways it’s covering King, either what he’s doing when he’s doing other things. One of the funniest things I found was this piece, in September of 1963 the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham got bombed and the four pre-teenaged young women got killed. One of King’s first responses to this, which I had not remembered, is to call for a nationwide boycott of Christmas shopping. He is so angry but he is also like, “This is not just a Birmingham problem, this is an American problem.”

The New York Times goes crazy and they write this editorial; it’s the craziest thing. I mean, basically it’s like war on Christmas; they accuse him of waging a war on Christmas and that basically he’s doing the same thing that these people who had bombed the church would be doing, and they would be turning Christmas into a day of hate if they did that. It’s insane, but I think it gets at the ways that the media is going to shape how we understand who King is, what he’s doing, and what he’s not doing. So, I think part of this idea of King turning his attention to the north after Watts is because the media turns its attention to the north after Watts in ways that it tended to not want to cover the Civil Rights Movement in New York, in the ways that it was covering the movement in Birmingham by 1963, for instance. A product of the time.

Then, I think King makes strategic use . . . One of the things that I came to realize also is this point of how he’s been in LA so many times and he’s been talking about police brutality before 1965. He talked about all these things but that shock after Watts, he’s strategic, he’s using that shock to open up more space to talk about things he’d been trying to talk about for years. He realizes there’s more space and so he’s also using it. In some sense, these papers are willing to give him a lot more space to talk about these things and to listen to things he’s been saying for a long time.

Yes, that’s really important. I hadn’t thought about it quite that way. That’s very useful. More questions are coming in. Someone says they would like to hear more of the discussion about the international connections of Dr. King’s work, and someone else said they would love to hear more about the internationalist nature of his stance and how that relates to the current Black Lives Matter movement.

Theoharis: A couple of things. One of the things that he and Coretta do shortly after the end of the Montgomery Bus Boycott is they go to India. They begin to make these international connections. But, I think one of the things, and I’ve talked about this a little at previous sessions so maybe people have heard me say this before, but when we want to talk about King’s internationalism we really have to begin with Coretta Scott King, because she’s an internationalist in many ways.

She comes to their marriage with an international decision; already she supports Henry Wallace’s third party candidacy in 1948 for the presidency. Wallace is running on a pro-peace, anti-segregation third-party platform, so she’s in some sense more political even than King is. When they meet in the early 1960s she starts to get involved in international women’s peace actions; she goes to Geneva in 1962 around global peace and issues; she joins the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom; and interestingly, when he wins the Nobel Prize in 1964, she really sees this as they now have a different responsibility, that their responsibility has shifted from just being to the United States to the world. She talks about starting to talk to him, to say you have to start coming out against U.S. involvement in Vietnam more publicly, that we now have this responsibility to the world. This is a very costly stand; she comes out publicly earlier than him, so she’s speaking out against the war at various events. In 1965 a journalist then asked him, “Did you educate her?”, and he says, “No, she educated me,” and we know then that by 1967 he was very out publicly and he certainly opposed the war long before 1967.

But I think really thinking about his internationalism, in part learning from her, I think that the vision that she has and those experiences that she’s having is really important.

Hagopian: No doubt, just the way that Black women in general are erased from the telling of the Black Freedom Struggle all too often, and then specifically how the monumental role Coretta plays in the development of King’s politics is so important. So thank you for adding that.

We’ve got some more great questions coming. Chris Wilson says, “I had a chat with Rev. Jim Lawson last year and he brought up an idea that I had been thinking about and that I think needs more research. For our recent history, Lawson suggested that following the LBJ Democratic Party’s reluctant backing of civil rights caused an anti-democratic small d backlash against racial progress that turned into a general anti-government movement, which is really what led to January 6th. In other words, racism drove what we are now seeing in the radical white extremists who see government itself as the enemy. I wonder what you think of that?

Theoharis: Well, I think I would like to take this in a slightly different direction, and this is partly because my head is in the north, which is that the other aspect I think we need to think about, because I think we tend to have this Nixon Southern Strategy idea, basically that Nixon and the New Right will find what scholars have termed the Southern Strategy, which is to speak a racial politics, but not as like vehemently and outwardly. That’s how you then move this group of moderate white working-class and middle-class people to the right.

But, I actually think the origins of that are not in the south but in the north, and I think what we need to see is that, and when we we see King talking about northern liberalism or calling out northerners, I think one of the things we see is that, and one of the things he’s recognizing is, “Okay, these allies might be willing to change the south, but they are not willing to change where they are, and if you make them change where they are, if you even start to talk about that, you’re going to get this backlash.” So he’s very much . . . one of the interesting things, he starts getting, for instance in 1964, people talking about this Wallace backlash and it’s so surprising that Wallace has the support outside the south. Then he’s like, “It’s always been there.” He’s constantly talking about this, and that people have not recognized that there is this anti-civil rights strand in the north that comes out when the change gets too close to home. There’s a larger commitment to civil rights, but then when it actually involves school desegregation at home, no. When it comes to actually changing your own housing, no.

I actually think what we need to spend more time thinking about is the ways that racial politics tend to be associated with whatever Reagan Democrats or the Southern Strategy comes out of in some sense these northerners in the early 1960s, who might again be willing to say, “Mississippi is a horrible, racist place and we should fix that,” but are absolutely saying no to school desegregation here in New York City. So, I think there’s the question of this right wing but I’m wanting to think about this middle and the ways that we’ve misunderstood the racial politics of the middle as the south driving it, when I think that’s too simplistic.

Hagopian: Yeah, that’s really interesting. I like the way you frame that. Thank you. More questions are coming in. Anything about what King said about the earth, environmentalism, materialism? That was one of the questions. Another one is asking about what King would be doing today. Then I have maybe one more question for you after that.

Theoharis: So, I don’t know about King’s environmentalism, although again my recent research suggests that there’s probably so much to find. I just have been amazed at how much,and I really suggest that people use King day to go back and read King, because I feel like the more I read him the more I’m like, “Wow, there’s all these things, even boxes I was putting him in, that you just have to get rid of.”

What would he be doing today? Well, I think one of the things is how uncomfortable King made people, how unpopular he was, and I think there’s something humbling about that, which is that all these papers are editorializing against him, they all come out against him when he comes out against Vietnam, they all are criticizing. And again, earlier than that, too. So, what it means to have to keep going in the midst of that public disapproval and hatred.

The last time King and Parks see each other she’s living in Detroit. He comes to this very fancy suburb of Detroit called Grosse Pointe, then a month before he’s assassinated he talks about this as the most disruptive indoor audience he ever experienced. He’s heckled so much that night, he’s called a traitor so much that night. She talks about what a mess it was: They were so afraid that he was going to be assassinated that night that the police chief sat on King’s lap. King is not a tall man; the police chief sits on his lap and they drive him into this school. He’s speaking in Grosse Pointe because they’re worried he’s going to be killed. So, what it means to just be confronting that level of opposition and hatred all the time.

I think one of the things about where King would be today, I think he would be making people uncomfortable in the ways that he was making people uncomfortable in 1968, or in 1963, or 1958. He believed in disruptive politics. Again, going back to where we started our conversation about policing, one of the things I just have been forced to think about a lot that I just really hadn’t was Dr. King’s body and what it means that he kept putting himself and his body in jeopardy, in some sense, in all of these arrests. Just thinking about what it takes to do that and with this understanding that having your body touched and manhandled in all the ways that his body was touched and manhandled by police. Just thinking about the actual person.

Hagopian: I really like that. You’re absolutely right, he would be disrupting things along with the disrupters of the 2020 uprising. I just love the way you always point out that those who try to create a dichotomy between Black Lives Matter and the uprising and Martin Luther King really don’t understand the legacy of arrests that he was committed to using to disrupt injustice. So, that’s great.

You mentioned his meeting there with Rosa Parks, and I thought maybe we would just end with one last question about his relationship with Rosa Parks, who you have written so extensively about. I would just love to hear more about how these two most celebrated figures of the Civil Rights Movement are often both misunderstood and mistaken. You have a new film coming out, which I’m so excited to see, about Rosa Parks. People here should definitely be ready to see that, to teach with it, and share it with others. I’m hoping you can talk about Rosa and Martin Luther King’s relationship, and Rosa’s attitude towards Martin Luther King.

Theoharis: What Jesse’s referring to is a documentary being made and finalized right now based on my book. The film is also going to be called The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, based on my book. It’s just been amazing to get to see her life come alive on the screen.

So, she gets disgusted later in life about the ways that he’s getting misused and misunderstood, and there’s this funny quote from her, where she’s also like, “He’s not just constantly dreaming, he was acting.” She starts pushing for a holiday, like many other activists, from the moment he’s assassinated, and she’s doing all this stuff. There’s this great photo of her the next year, on the first anniversary, where she has this huge bullhorn and she’s wearing almost like a cowboy hat or something — I don’t know, some sort of funny hat — and she pushes for this holiday.

But, then she also comes to see the way that he’s getting stripped of who he was. So that’s interesting. That’s later in life. I mean, one of the things, again thinking about King as an actual person, he comes to Montgomery, he’s 25, to pastor at his first church and and he comes to an NAACP meeting. He speaks one night, this is right after the Brown decision, and she just is flabbergasted because he’s just such a good speaker. He’s so young; I mean, he’s 25 then. If you look at King, he just looks so young, and she is just so proud. She’s 42 at this point, or 41 maybe, when she first meets him, so they’re not exactly peers. They’re not the same age. King has graduate degrees, and Rosa Parks doesn’t get to go to college. She’s working class, he’s more middle class. But she’s just so proud of him and when you see him through her eyes it’s like watching this young man turn into this incredible national leader, just watching it before your eyes. Again, I think it reminds us that King is a real person, making choices and figuring it out, and just how remarkable it is.

Hagopian: That’s so wonderful and such a great place to wrap up this conversation. Thank you so much, Jeanne, and thanks to everybody who’s here with us this evening.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

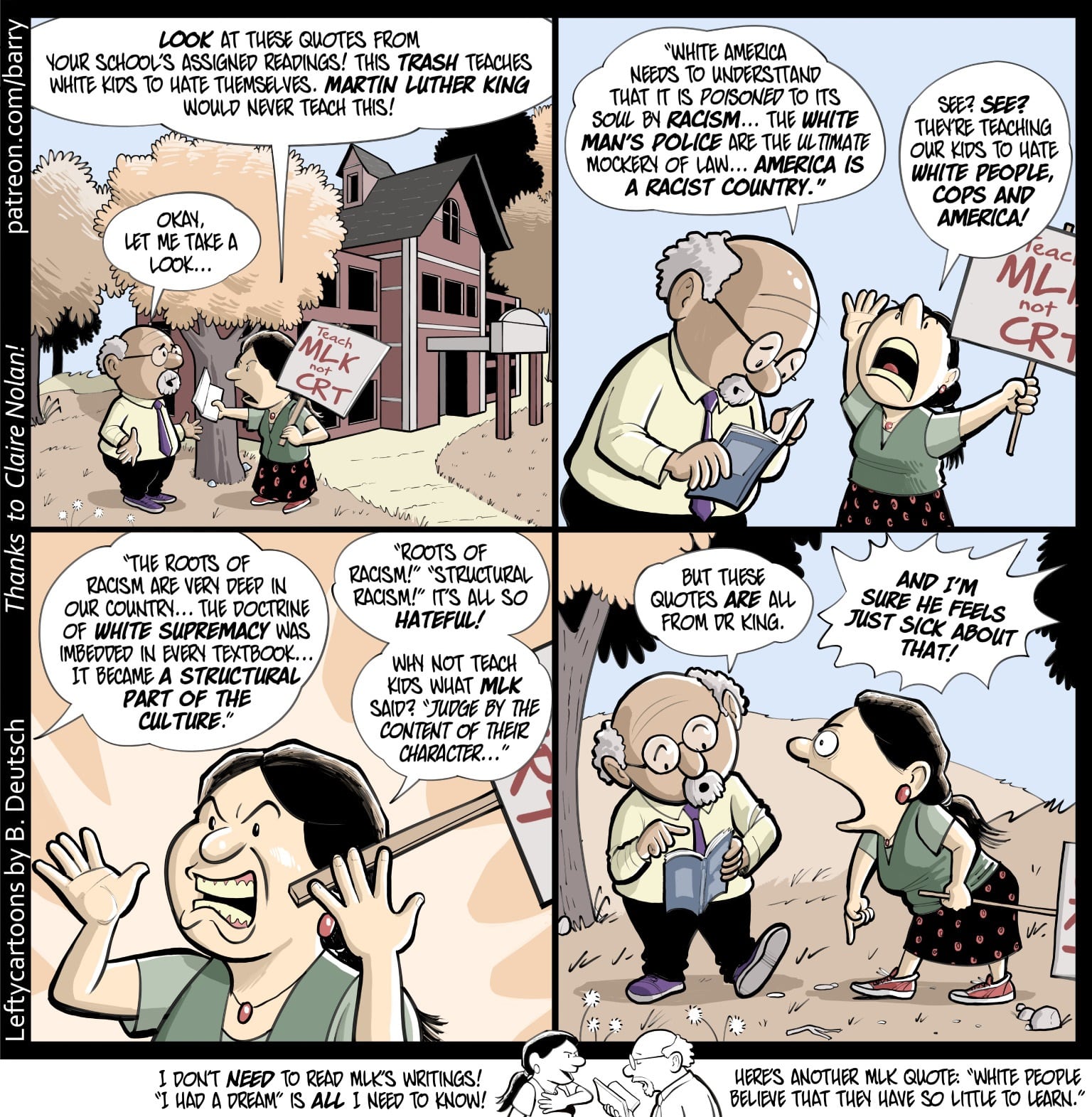

Here are many of the lessons, books, articles, videos, and more recommended by the presenters and also by participants. We start off with a cartoon reprinted here by permission of artist Barry Deutsch.

Used with permission of Barry Deutsch.

Lessons and Curricula

|

A Revolution of Values Teaching Activity based on speech by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The Rebellious Lives of Mrs. Rosa Parks Teaching Activity by Bill Bigelow “Riots,” Racism, and the Police: Students Explore a Century of Police Conduct and Racial Violence Teaching Activity by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca, Zinn Education Project |

Related Books

|

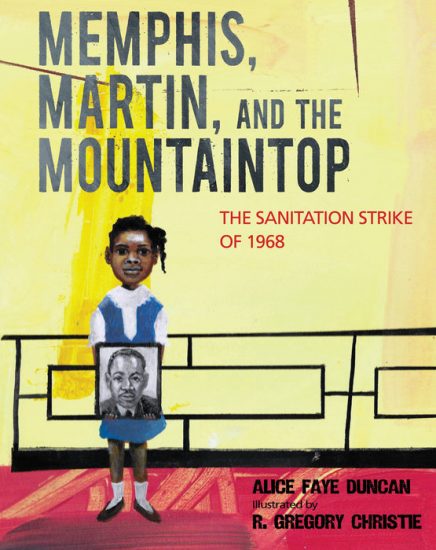

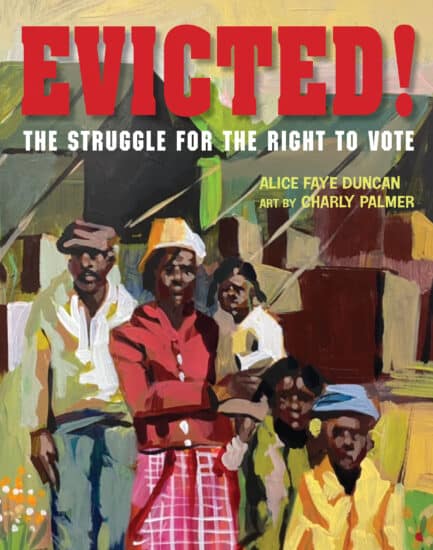

In addition to Jeanne Theoharis’ A More Beautiful and Terrible History, the following books were referenced. As Good as Anybody: Martin Luther King Jr., and Abraham Joshua Heschel’s Amazing March toward Freedom by Richard Michelson. Illustrated by Raul Colón (Knopf Books for Young Readers) Evicted!: The Struggle for the Right to Vote by Alice Faye Duncan. Illustrated by Charly Palmer (Calkins Creek Books) Memphis, Martin, and the Mountaintop: The Sanitation Strike of 1968 by Alice Faye Duncan. Illustrated by R. Gregory Christie (Calkins Creek Books) The Radical King by Martin Luther King Jr. Edited by Cornel West (Beacon Press) |

Related Articles

Videos

|

At the River I Stand: Documentary film on the African American sanitation workers’ 1968 fight for human dignity and a living wage in Memphis. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.: “Beyond Vietnam” Dramatic reading of Dr. Martin Luther King’s “Beyond Vietnam” (1967) speech by Michael Ealy. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in His Own Words 2020 segment of Democracy Now! |

This Day In History

Participant Reflections

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

Dr. King was a dynamic learner and strategist who was in deep relationship with others in movements, including global peace movements, economic justice movements. He was just as concerned about northern liberals not addressing racism where they live. At the time of his death, he was a radical and 2/3 of the American public did not approve of him. He believed in social democracy and fought against racism, militarism, and poverty. He was a disruptor who made it his business to make people uncomfortable. Before his assassination, he lived under the constant threat of death.

How King was very critical of northern liberals and how this is not often talked about or taught.

The South was often used as a Proxy for the North so the North didn’t have to address racism. King saw capitalism as a problem for Civil Rights. The media plays both sides of MLK to shape how we see him (i.e. the North’s media shine light on the segregation of the South but not on the North).

That MLK was more radical than commonly taught and that he recognized the racism of the North.

How many times King was arrested and the torment he went through. It reminded me of today’s times and how little Black lives are valued by police. The fact that this side of MLK’s history is so relevant today, it holds so much power to inspire the youth. As a 22-year-old educator of color, I am determined to make a change and teach his truth. A quote from tonight — King expressed it is “not true that America is progressing towards justice.”

The storytelling of MLK and Coretta Scott King driving the international side of expanding civil rights.

MLK was very involved in Northern racial politics and this has been simplified in our textbooks as a Southern issue. King was widely unpopular and criticized in the 60s.

Dr. King was always learning, growing, and developing his political theory and tactics. He was not suddenly radicalized by Watts, but rather saw it as an opportunity to expand his public political analysis!

What will you do with what you learned?

This will inspire me to focus more on King’s effective radicalism and how his work was not so much focused only on racism in the South.

Incorporating more of Rev. Dr. MLK Jr.’s writings and primary documents into class and lessons in order for students to understand his ideas beyond the surface of what they have learned previously. Discussing the more complex history of the Civil Rights Movement, the role of the media, etc.

Educate, organize, agitate.

I’m going to use this information to guide my own research, temper my education, and enhance my own eventual lessons in the classroom.

I have more resources to #TeachTruth and share with students to query our course materials and always question the narrative.

Keep using King to speak back to what is happening today. What would King do? “Reclaim” King, if you will.

First, I want to purchase Dr. Theoharis’ book. I went online and purchased the book on the misuse of civil rights history. I now have some language to talk to students about other sides of MLK that they never hear.

I teach Dr. King using ZEP resources and will continue to do so, armed with even more background knowledge!

I am a literacy teacher, a yoga teacher, and a white women’s caucus participant/sometimes leader. This is important for me to prevent white women in my working groups across these different jobs from “fluffing up” the conversation around MLK — myself included — and being able to sit in the discomfort that will inevitably arise. I loved Professor Theoharis’s suggestion to read King on MLK Day. Read his actual works. I’m definitely on board with that.

Additional comments

Engaging and informative.

Dr. Theoharis is such a knowledgeable and expressive speaker, I’ve been so excited for her classes with this project and thoroughly enjoyed reading her work. And Jesse Hagopian continues to lead with questions that inspire the best from speakers and thoughtful citations of their work. I’d also like to shout out to my small group from this session, well facilitated by Julita and with a cross-section of educators from in-school to retired and teaching across the nation. I really appreciated hearing from each member of this group.

Thank you for organizing this. We need this so much!! It is both intellectual and psychological. We have been under so much assault!

I now have even greater respect for this man’s brilliance and commitment to humanity!

I was on Dr. King’s staff in Chicago in 1965-66 and co-edited a book on the Chicago Freedom Movement. I really appreciate your efforts to put his Chicago work in the context of his earlier concerns about the North — and reminding us that he had spent six years in the North before Montgomery. The internal colonialism perspective was strong with all of us in Chicago; that was where I first encountered this perspective (I was 22). I’m also really interested in how we can connect his work to the Black Lives Matter movement and related issues today.

This is an awesome organization. I am sharing this information with my team. Teaching truth is what matters.

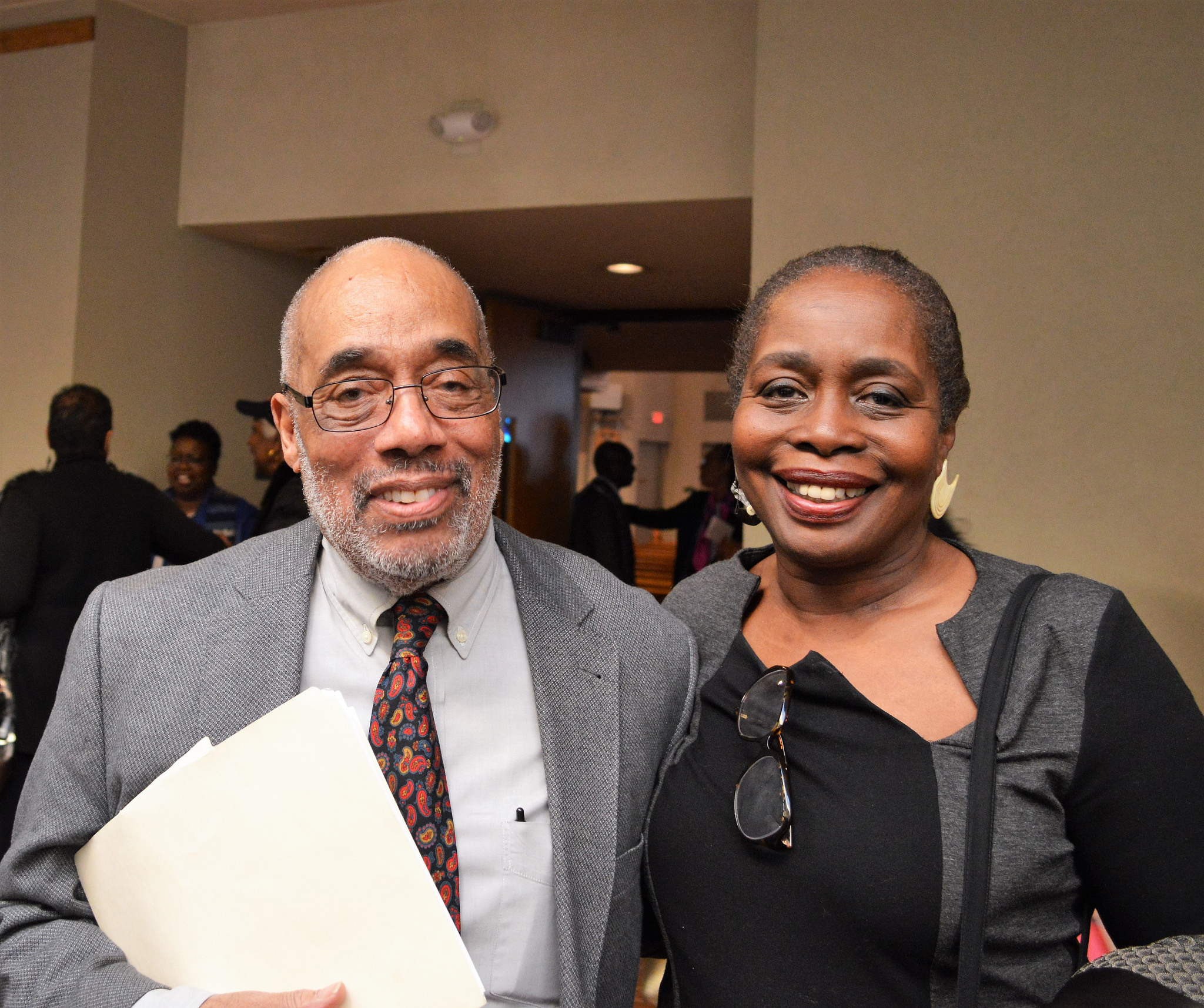

Presenters

Jeanne Theoharis is a distinguished professor at Brooklyn College. She is the author or co-author of nine books and numerous articles on the Civil Rights and Black Power movements and the politics of race and education. Her books include the award-winning titles The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks and A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, and editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn