On February 22, 2022, KOOP’s Civil Rights and Wrongs aired a 45-minute episode on teaching people’s history and the Zinn Education Project report, Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction.

|

|

|

|

| Michelle Manning-Scott | Jesse Hagopian | Signe Fourmy | Kerry Green |

Michelle Manning-Scott, along with Bob Dailey, hosted three guests for the discussion:

- Jesse Hagopian, a history teacher in Seattle and a lead organizer with the Zinn Education Project

- Signe Fourmy, director of research and analysis for Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery at Villanova University and instructor of history in the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Texas at Austin

- Kerry Green, U.S. history teacher and social studies department chair at a Dallas area high school

Listen to the full episode below.

Transcript

Note the transcript below is for the portion on education. It is auto-generated with Otter and lightly edited. There may be typos and omissions.

Bob Dailey 00:01

This is KOOP HD1 HD3. Welcome to Civil Rights and Wrongs: The State of your Civil Liberties in the Lone Star State. The views expressed here are not necessarily those of the co-op board of directors, staff, volunteers, or underwriters.

Michelle Manning-Scott 00:55

Our thanks to Rocky and Le Chateau Daddy-O for that lead in. . . This past December, Senate Bill 3 (SB3) became a new law here in Texas, a law that aims to restrict how history is taught in the public school systems of Texas, as reported by the Texas Tribune in early December 2021. Under the new law, quote, a teacher may not be compelled to discuss a widely debated and currently controversial issue of public policy or social affairs, end quote. The law doesn’t define what a controversial issue is. If a teacher does discuss these topics, they must quote explore that topic objectively and in a manner free from political bias, end quote. The Tribune also noted that the new law requires at least one teacher and one campus administrator in each school district to attend a Civics Training program that will teach educators how race and racism should be taught in Texas schools. This training is to be created and implemented by the Texas Education Agency (TEA) no later than the 2025-2026 school year.

With more than 1,200 school districts in Texas, the estimated cost to develop and implement the training program could be around $14.6 million annually, according to the Texas Legislative Budget Board. As further cited by the Tribune article, some of the specific objectives of this new law include restricting access to certain materials, such as the New York Times’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1619 Project, which is a collection of essays that center how slavery and the contributions of Black Americans shaped the United States. With this law, students cannot be required to read the 1619 Project essays.

It also bars students from receiving credit for working as a volunteer with a political campaign or interning for companies organizations where they will be lobbying. Also, any school district that uses an online portal to assign learning material has to give parents access. In the meantime, TEA has been advising school administrators that teachers should just continue teaching the current curriculum until the State Board of Education revises the Social Studies curriculum over the next year.

Good evening, and welcome to Civil Rights and Wrongs on KOOP 91.7 in Austin and streaming live at KOOP.ORG. I’m Michelle Manning-Scott guest hosting the program this evening alongside regular host Bob Dailey. We have three guests joining us this evening. Jesse Hagopian is a history teacher and student advisor in the Seattle area who is currently on leave from the classroom to work as a lead organizer with the Zinn Education Project. Signe Fourmy is director of research and analysis for Last Seen: Finding Family after Slavery at Villanova University, as well as a lecturer and instructor of U.S. history at the University of Texas at Austin. And Kerry Green teaches U.S. history and is the social studies department chair at a Dallas, Texas area high school. And she is also an adjunct instructor of U.S. history at Dallas College. Welcome to the program, everyone.

Kerry Green 04:22

Thank you.

Jesse Hagopian 04:23

Thanks so much.

Signe Fourmy 04:25

It’s nice to be here.

Michelle Manning-Scott 04:26

Obviously, the three of you have a passion for history. And I also assume teaching history past present all in common. So why don’t we start by having each of you give a brief synopsis of your personal backgrounds and possibly where that passion came from. And also what in your background and experience has led you to your belief in the importance of always teaching an accurate accounting of our history, even if that history maybe sometimes uncomfortable to learn. Whoever wants to start first. Maybe Signe?

Signe Fourmy 04:57

Sure. So I taught middle School in South Houston for 11 years before I returned to graduate school to get my PhD from UT. And then after I graduated, I became the director of analysis at the Last Scene project. I guess I don’t know if passion is the right word. But my dedication to making sure that we teach history responsibly, started in the classroom when I was working with students who wanted to see themselves reflected in the narratives to see themselves reflected on what we were studying and talking about, and they just weren’t there. And so I had to find ways to make sure that, that they did that, that they could see themselves in the history.

Michelle Manning-Scott 05:36

Jesse, would you like to go next?

Jesse Hagopian 05:39

Absolutely. Well, I grew up a student in the Seattle Public Schools. And as a Black, mixed race boy, I rarely saw myself reflected in the curriculum, I had, maybe one or two teachers that looked at African history and looked at the immense contributions of Black people in this country, to our nation, to our society, to any semblance of democracy that we’ve had have largely been achieved through social movements that Black people played huge roles in. And all this was hidden from me. And so I really didn’t value education, because I didn’t see myself in it or see myself included as part of it. And so when I finally discovered the power of education through some of my college courses, I wanted to become a teacher myself to help youth, especially Black youth find themselves in the curriculum much earlier than I had. So I began teaching in Washington, DC, in 2001. And, you know, I really want to help shield our students from what Professor Henry Giroux has called the violence of organized forgetting that is going on in our country right now. There’s a organized effort to try to erase the contributions of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. And it’s incredible to see what happens in the magic in the classroom, when students see that great contributions of people like them.

Michelle Manning-Scott 07:13

I like that, quote, we might get into that later. I had not heard that before. Kerry, would you like to give us a little bit about yourself.

Kerry Green 07:20

Sure. So I came to education light as a non-traditional student and was initially not going to teach history and then discovered a passion for it. And I think the best way to explain my dedication to telling the truth of American history really has a lot to do with my own path wrestling with my own whiteness. And appreciating the lack of education I had that the narrative that I had been given, that was white and patriarchal. And as I became an adult, and began to wrestle with my own position as a white feminist, and I began to realize that I had privileges that basically I didn’t understand what other groups had suffered, even though I understood very intimately how patriarchy functions.

And really what has happened over especially the last 10 years, but I would argue probably the last 20, has been a real sense of reckoning that, I want to try to create a cognitive dissonance for my students to prepare them so that whenever they’re ready, and for some of them, that’s at 16. For others, I don’t know when that’s going to be, but to prepare them to accept the fact that there is a narrative out there, that is not true. And that is being told from a power perspective, with a very intentional purpose behind it. And that looks different if you’re a white female, than if you’re a Black female than if you’re a Black man, if you’re Indigenous, if you’re a Person of Color, there’s all these intersections that shaped that power dynamic. And if we continue to ignore that story, and the way the story is crafted to communicate power, then we don’t understand how we’ve gotten to where we are. And so I feel very passionate about in my own small way, disrupting those power dynamics.

Michelle Manning-Scott 09:21

Thank you, all of you for those insightful introductions. I came to this topic for the program through finding out about the Zinn Education Project Online. So, Jesse, since you’re an organizer with the Zinn Education Project, would you feel comfortable giving us a brief overview of it? How and when it was founded, its purpose, maybe touch on various campaigns it has instigated and who the Zinn Ed Project is targeted for.

Jesse Hagopian 09:48

No doubt. Thank you, Michelle. So the Zinn Education Project takes its name from the great historian Howard Zinn whose A People’s History of the United States book did something that few textbooks do in this country, it really wanted to look at history not from the position of the rich and powerful, but from those who have been impoverished, oppressed or exploited. And he analyzed wars, not from the perspective of the president who declared them or the generals who carried them out. But from the perspective of the soldiers that had to die in those wars, or the people that were being colonized. Right, he wanted to analyze enslavement, not from the point of view of the needs of the national government and the economy or, or the slave owners, but from the African people who were kidnapped and enslaved.

And so by doing a bottom up view of history, we get a much different look at our nation’s past and the Zinn Education Project promotes and supports this teaching of A People’s History and classrooms all over the country. Zinn Ed Project was founded in 2008. And it’s really just been about introducing students to a more accurate, a more complex and a more engaging understanding of our nation’s past than is found in traditional textbooks and master narrative curricula that we see all over the country.

And the Zinn Education Project has over 140,000 educators registering on our website, and you know, we get around 15,000 new registrations a year. So it’s incredible to see people resisting the whitewashed curriculum that believes out the struggles of indigenous people, black people, women, LGBTQ folks, all of these different groups that have been marginalized are brought to the center in our curriculum. And our website offers free downloadable lessons and articles that’s organized by theme and time period and grade level.

So we have all these different interactive lessons, engaging lessons on the Civil Rights Movement, or Native American resistance to colonization, police violence, voting rights, the Black Panther Party, climate change, so many other social movements. And we have several campaigns that we’ve launched. One is to teach climate justice. We have campaign around abolishing Columbus Day and teaching about Indigenous Peoples’ Day. And we have Teaching for Black Lives campaign as well, that includes a monthly Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online course, where myself and a couple other hosts will interview historians about what is often mistaught in our schools, and how we can teach the Black Freedom Struggle more accurately.

Michelle Manning-Scott 12:50

Yeah, it’s a wealth of information, I wasn’t even able to like touch on a lot of it, going through it myself when I came upon it. And I have to throw in a quick mention of my alma mater, Boston University, where Howard Zinn taught for, I think, 24 years. And I was there for his last year that he was teaching there 1988, which was into my freshman year. So unfortunately, I was never able to take any of his classes, although I’m not so sure I would have had the wherewithal at the time to know to do so. However, it was totally coincidental that I came upon the Howard Zinn educational project online not too long ago, and which of course, led to this program. So you talked about the campaign’s of the Zinn Education Project.

And so we have you all here today, basically, to talk about the Teaching Reconstruction campaign. If one of you or any of you want to kind of delve into a little bit more of the overview of how you’re involved in that, maybe and how you came to know about it, that was hoping we could kind of get a review that particular period of our history, the post-Civil War Reconstruction period, since I noticed that that’s one of the facts that was mentioned on the website, that in 2016, the National Parks Service described Reconstruction as one of the most complicated, poorly understood and significant periods in American history. And even as ongoing crises with obvious links to the Reconstruction Era continue to reinforce its significance today, most people living in the United States know shockingly little about the policies, people conflicts and ideas that shaped Reconstruction and its aftermath. So I just thought pointing that out, because listeners here to the program may not know some of the facts and the circumstances surrounding Reconstruction.

Kerry Green 14:34

I was going to speak to it from a teacher’s perspective, which is that the Texas standards are woefully inadequate. Now, that being said, you can teach the standards. As of this point, there is nothing inherently objectionable in the list of the standards, with the exception that they leave out huge pieces of the story, right. And the chapter from a teaching perspective, and as a department chair, his teachers are the product of the educational system. So you take teachers that have been trained, whether their secondary, and they’ve been specifically trained for social studies or their elementary, and they’ve kind of received across disciplinary, many of those teachers, especially considering the percentages if you look at and I think Brookings did a report in the last year or so, that was saying over half the Social Studies teachers are white, and even more than half are men. So how do you take that cohort of people that have been shaped by this current educational system and have received this very sanitized, very straightforward, very minimalistic interpretation of Reconstruction, and you hand it to them, and they are supposed to teach students the complexity of it, and they teach it very much.

And I think the Zinn report mentions this, this kind of sense of progress of ever improvement, right, without focusing on the very intentional ways in which the South in particular, the North in more kind of de facto, rather than de jure ways, and then not to mention the ways in which politics just kind of raised their hands and said, “What are you going to do?” and kind of walked away from the issue of racial justice. You know, once U. S. Grant leaves office, and the prosecution of the KKK becomes less important, when that begins to happen, there’s very direct consequences for that. And so the narrative that has shaped our current teachers in the classroom, and how those teachers take these Texas standards, if they just teach the standards as they are, it is inadequate. They have to intentionally want to go out to bring in those other stories into way that perspective.

And even then, there’s a huge weight with how do you tell this story that is, on one hand, the story of hard work and achievement in the face of incredible odds, and yet also the story of oppression. To do this, you have to talk about the oppression and the violence, and yet also celebrate the ways in which Black communities and Black individuals form success. It is hard, and our teachers are not prepared for that. To me, that is the greatest challenge. That’s one of the reasons why I think what the Zinn Education Project is doing is so incredibly important, because it provides an avenue by which any teacher can access a lesson plan. And they may not know everything about it, but they can pull that lesson plan in. And they can begin to implement that, because we’ve got to meet the teachers where they are. And there’s a huge gap in that particular area. That is the intentional product of schooling over the last 100 years.

Signe Fourmy 17:59

Going off of something that Kerry said is I think one of the biggest problems with teaching Reconstruction is it’s simply a structural issue. By the time you get to Reconstruction, it’s the end of the calendar year, you’re racing through the test for eighth grade, at least to get through the state assessment, you’re trying to get through all these things. And I think people just ignore it, they teach it from the top down, they teach it as a political and economic period of time, they completely ignore the social aspects of what was happening on the ground. And I think that’s part of the detriment, building off what Kerry said, teachers lack the resources to do this. They lack their own education to do it with authority. And I think because of so many of the difficult topics that we encounter in this period, they’re reluctant to bring these topics into the classroom, because they don’t think for whatever reason to their students can handle them. And I think it’s been shown time and time again, that students are capable of dealing with these topics in intentional important ways. But I think teachers don’t know how to do it effectively. They don’t have the resources to do it effectively. And they’re not comfortable talking about these topics.

Jesse Hagopian 19:15

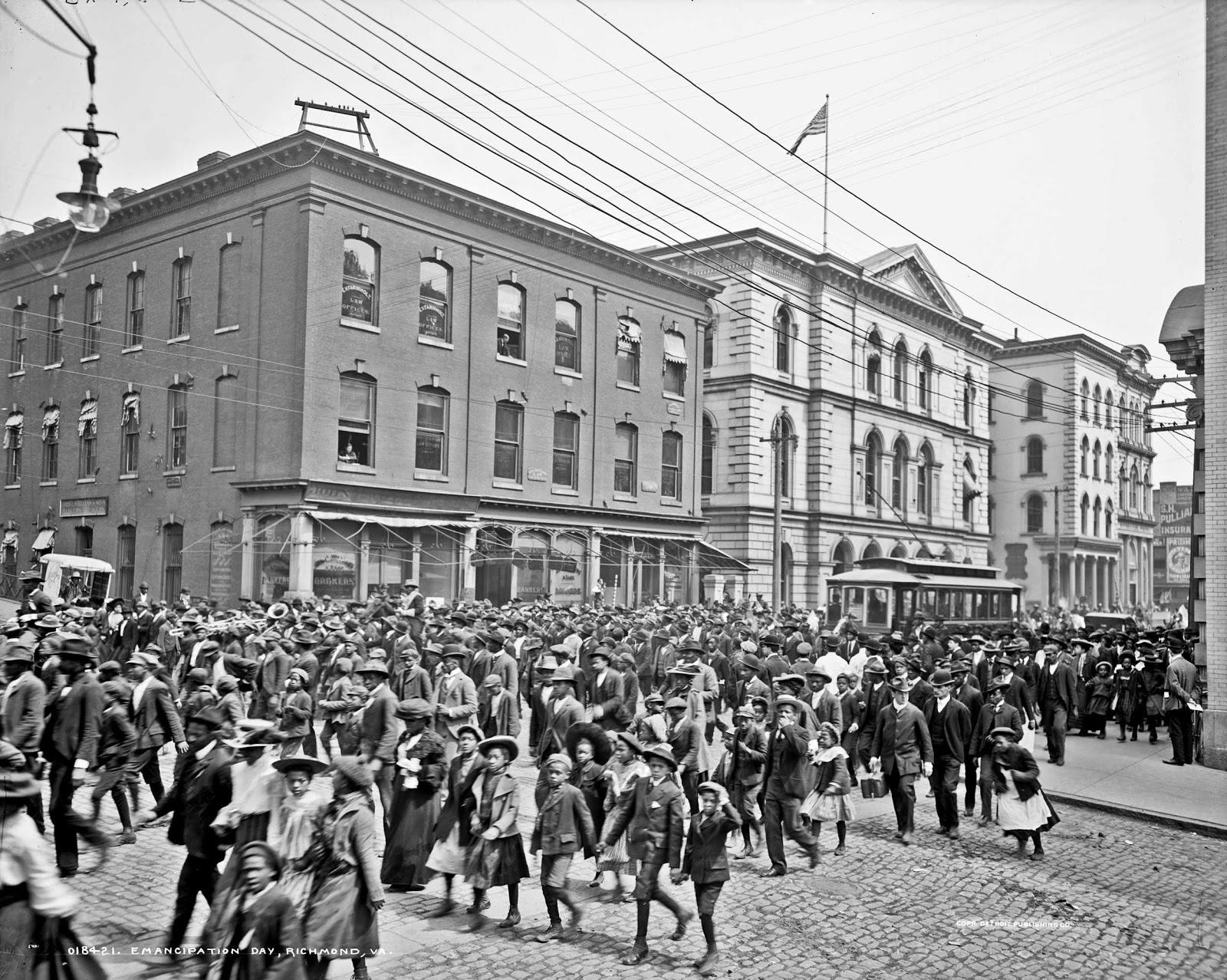

Yeah, all of that is exactly right, and why we wanted to release this report in the first place. But I want to begin with just saying a word about the incredible time period that Reconstruction is and what’s lost when we don’t teach this history because Reconstruction was a time of unprecedented change. And one of the few times in our nation’s history where there was a major undertaking to ensure that Black lives mattered in our society and were valued in the nation. And really, the central political questions during Reconstruction were about who would control the land and who would control the labor with the treasonous white supremacist Confederates who adjust killed hundreds of 1,000s of Americans get to continue to control the land and the labor? Or would Black people come to gain full political rights? And it was really an open question during this time period. You had formerly enslaved people demanding land ownership, property rights, fair labor contracts. They were talking about progressive taxation for state and local level social services. And you had over 1,500 Black Americans elected to office for the first time, there were majority Black districts who elected a lot of these Black officials. And in the 1860s and 1870s 16 Black Americans served in Congress, about half of whom were formerly enslaved, just mind boggling, right? And Black communities founded the South’s first education system, built over 1,000 new schools.

And this was the time of the passing of the 13th Amendment that abolished slavery, which we know there was a great loophole in that — except for persons who have committed crimes — and that opened the door to mass incarceration today. But the 13th Amendment, the 14th Amendment guaranteeing citizenship for all people born here and the 15th Amendment guaranteeing voting rights. And you really can’t understand our society today. You can’t understand the massive attack on voting rights with all these voter suppression laws.

You can’t understand the rise of mass incarceration without understanding the promise of Reconstruction and some of the great advancements during this time period. And also without understanding the massive white supremacist backlash that occurred during this time when you saw the rise of the Klu Klux Klan as a way to stop these great advancements. And then you saw an agreement struck between Northern industrialists and the former Confederates, who decided it would be more expedient to return power to the former Confederates, and disenfranchise Black Americans.

Kerry Green 22:29

You know, Jesse, I would add to that, that part of the importance of recognizing that agreement between Northern industrialists and southern white supremacists, is that part of the myth that we tell ourselves is that, you know, we all realized how bad slavery was. And in reality, if you dig very deep into the Civil War, you understand that for the North, it was about how dare you leave the Union, it had very little to do with Black civil rights. And in fact, the North had a very spotty record on how that was handled prior to the Civil War. And so it becomes too superficial, not only to say, this is a problem in the past, but to say this is a southern problem. It absolutely is a Southern problem, but it’s an American problem. And that agreement between Northern industrialists and southern white supremacist would not have happened, had there not already been some lack of interest in promoting social justice. And I think you see that if you connect the 14th Amendment with nativist movements of the late 1800s, during the same Reconstruction period, and how the 14th Amendment, if you interpret it from a sense of birthright citizenship for people from China, people from other countries, Italy, wherever talking about women, if you start to position those intersections, the fact that the 14th Amendment got passed is to me the most amazing thing ever, because clearly, I don’t think they understood what they were passing.

Bob Dailey 24:09

I’m just had a question. I’m not a historian. But I’ve learned so much during this radio show, among other things. One of the ebbs and flows in history that I’ve noted, is that just after World War I, there seemed to be a terrible time for Black people in the U.S., you know, we had Tulsa there. We had all these Confederate statues at UT Austin. We had soldiers coming back from WWI Black soldiers who were treated miserably. There were riots. You know, we’re talking about post Civil War and Reconstruction. What was it that seemed to hit after WWI? One person I spoke with once pinned that on Woodrow Wilson, but even the KKK seem to come into New Power, they’re in the early 20s. I just curious if any of you have any insights about that?

Kerry Green 25:06

What I teach my students, which is that there’s similarities to today, where you have technological disruption, you have globalization, disruption, that make people revert back to comfort zones. And sadly, the failure of the progressive movement to address race and to address justice in that perspective, as far as racial identity, that was the reverting back, there have not been enough protections put in place. And that’s how you get there.

Jesse Hagopian 25:41

I would add that, upon returning from WWI, Black people had an increased sense of their rights to full citizenship, they had just risked their lives to defend our country, and we’re coming back from the war and being lynched. And that created an increased sense of injustice, and Black people began organizing and speaking out. And one of the ways that the first Red Scare that emerged at this time was used was to attack this movements for racial justice and claiming that any advancement from black people was a product of Bolshevism abroad. And those narratives got recycled during the second Red Scare during McCarthyism as well that any advancements for civil rights were simply the product of the Kremlin. And so I think that you had a situation where a lot of people who wanted to maintain the white supremacist status quo in the United States felt threatened by black people who were increasingly organizing for their civil rights.

Bob Dailey 27:03

Interesting, thank you for those insights. Like I said, it’s just one of those things that kind of hops off the pages that maybe you know what was going on.

Michelle Manning-Scott 27:13

We’re speaking with Jesse Hagopian, Signe Fourmy, and Kerry Green, three educators who teach U.S. history and advocate and promote the accurate teaching of history from the narratives and perspectives of all those who lived it.

. . .We’re speaking with Jesse Hagopian, Signe Fourmy, and Kerry Green, three educators who teach U.S. history and advocate and promote the accurate teaching of history from the narratives and perspectives of all those who lived it. Let’s continue. So if we want to go back to discussing a little bit about the teaching of history, I specifically wanted to get to some of the state legislative issues, bills, proposals that are swirling around all over the country right now, specifically here in Texas, it was the passage of Senate Bill 3 other states are doing similar things, if you wanted to talk about that, and how history teachers around the country are dealing with these issues, talking about these issues amongst themselves and also parents, community members. I’m just curious, and also the involvement of the Zinn Education Project in any way in addressing what’s going on.

Kerry Green 29:22

Well, I can only speak to my experience in the Texas context and particularly in the Dallas area context, which is the teachers that are interested are still interested and are still committed and doing what they want to do. I think if you are dedicated to trying to bring in other narratives, trying to include Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, you’re still trying to do those things. I do think it makes you pause a little bit. You know, you have a little more of a deep breath over certain lessons than others. which is not something you would have had in previous years. I’ve been fortunate, I can’t say that it’s influenced how I’ve taught, but it has created a little more anxiety. But I also think that the saddest part to me and this is what I observed from my conversations with other social studies teachers, is the teachers who are not inclined to do that either because they lack the background knowledge, or they’re coaching three sports, so they don’t have time to seek out other materials, or maybe they are uncomfortable or nervous, whatever the situation is, this gives them an excuse to not do that. And so it creates that chilling effect.

Jesse Hagopian 30:44

Yeah, these anti-history laws that are passing across the country, to ban the teaching of structural racism, the 1619 Project, the Zinn Education Project, any kind of Critical Race Theory, are really scary. Today, you have more than 17.7 million public school students who are enrolled in almost 900 districts across the country that have had their education cut short by one of these bills that attempts to require educators to lie to their students about the past. They try to mandate things like you can’t teach that the United States is structurally racist. And it’s to me just a boundless satire of a situation where you have Juneteenth becoming a federal holiday, at the same time that it becomes illegal to teach about where that holiday came from, and many places across the country, and banning that the United States is fundamentally racist or sexist, is just absurd, right? If you look up the definition of fundamental in Merriam Webster, it says serving as an original or generating source, we have to reckon with the fact that the original source of our country was the genocide of Native American people who were here first, and the enslavement of African people. And you literally can’t teach about the founding of this country without talking about systemic racism. And what I find so ironic about these bills is that they confirm the central thesis of Critical Race Theory, right? They want to ban Critical Race Theory, which states that any advancements towards anti-racism are always met with a white supremacist backlash. And that was certainly the case during Reconstruction, when you had 1,500 Black people being elected to office and then the massive white supremacist backlash occurred where you have the Ku Klux Klan come into formation to terrorize Black communities. They burnt down some 600 schools in the south serving Black kids during the Reconstruction Era.

And one of the other central claims of Critical Race Theory is that race is a social construction. And in South Carolina, there’s a bill that would require educators to not teach that race is a social construction. And what that would do is return us to explanations of race that were prevalent in the early 1900s, under a philosophy known as eugenics that was a white supremacist pseudo science that tried to base race in biological differences, when scientists have clearly shown over and over again, that there’s only one human race and so that race is a social construct based on power relations. And that’s something our students deserve to learn about. And I guess I would just end by saying one of the major reasons that these people who are advancing these anti history bills give is that they don’t want to shame white children. And they say that teaching this accurate history of race of enslavement and the consequences today is about shaming white kids or teaching them to hate their own families.

And I think nothing could be further from the truth. I think that white students deserve to reckon with the fact that we live in a society where white families have 10 times the amount of wealth as the average Black family. This is a fact and revealing that fact in the classroom is not about shaming white students. In fact, it is those who deny structural racism, I think that end up leading white children to suspect that maybe they are personally responsible for racial disparities that they see, rather than understanding the ways that systems can work to perpetuate inequalities. I think sometimes regardless of the intentions of the individuals who work in those systems. So, we want white kids to learn about white people have joined movements for racial justice and learn that while there are lots of privileges for being white in this society, there would be even more privileges and benefits to living in a society that treats everybody equitably.

Kerry Green 35:38

And I would echo that, just the that, you know, Texas, just in the last couple years passed the law that we’re required to talk about the Holocaust and genocide. And so here, they’re asking us to talk about the Holocaust and genocide, and essentially the systemic racism, and ethnic biases against people of the Jewish faith and Jewish ethnicity. And yet, we’re not supposed to be talking about race, that hypocrisy ultimately knows no bounds. And I would argue that it’s incredibly naïve. The point of these laws is to terrify teachers, it’s not really to control what’s being exposed to the kids. Because if you have students that have Netflix, that have TikTok, that have friends, they’re being exposed to content. But what they’re intentionally trying to do is control teachers so that we can’t give them the context and the tools with which they can understand this material. And you’re absolutely right, they’re actually making the problem worse, by denying that kind of educational laboratory where students can look at these ideas and evaluate them and begin to make sense of them within their own paradigms.

Signe Fourmy 37:04

I teach African American History at UT. And one of the things that I find in the survey course, the students that are in this class are self selecting, right? They sign up to take this class instead of know, maybe the regular survey class or in addition to a survey class, because they want to find out what they’ve not been taught. And it never fails, that they come to me or they email me and they say, Why haven’t I been taught this? And some of them are outright angry about it, right? Like, they start to question. And one of the things that I really tried to hit home with them, because I taught in the public school system for 11 years. So I try to hit home with them that what they’re being taught in public schools is controlled by somebody else. And they need to start questioning what they’ve been taught and what they’re not being taught. And for the most part, you know, they get it, they want to know this history. And I think it’s incredibly important that it not be an elective. And I know that’s a big straightforward in Texas, creating the high school elective that allows African American history to be taught. But I think it’s also problematic, because you’re allowing the differences to be reinforced, they have to opt in to get this history instead of being standard.

Kerry Green 38:18

I’m working on a doctorate in educational leadership and policy studies. And there is no logic to it. There’s a disconnect between those who care about the education of students and those who are making the policies that shape the education of students, and the people making the policies have an agenda that’s based on something else entirely.

Signe Fourmy 38:38

Absolutely. And even if you look at the TEKS, for the African American elective, they all focus on larger issues like sharecropping, or concepts like violence, which are extremely important. But a lot of times, they’re looking at these bigger concepts, miss the forest for the trees. One of the things that Zinn does really well, and one of the things that last scene tries to do is to think about the everyday experience of what this history was like for those who have lived through these moments. I think, and I kind of alluded to this earlier, we need to approach reconstruction in a different way we can approach from top down thinking about political economic things being taught, but we also need to look at formerly enslaved people. And this is a different kind of reconstruction for them. They are literally pursuing the reconstruction of their families of their communities. They’re trying to put their lives back together. More importantly, for me, at least is thinking about what that actual experience was and getting students to understand that it’s a lived experience, and getting them to look at the records and to look at the primary sources. I think you can teach this history without necessarily saying, you know, critical race theory in the classroom by teaching them the documents focusing on the primary source.

Kerry Green 40:01

Yeah, that’s how you do that. And I think the powerful message of Reconstruction is literally the grassroots, whether it’s reconstructing your family or gaining access to local politics or getting a state senator, the grassroots movement is incredibly powerful. But I think that’s the part that scares the powers that be if we really start talking about people on the ground, saying, This is what I want to reconstruct, this is what I want to make, I want my government to be in my image. And if we start doing that, we start challenging the narrative. To me, that’s the power of Reconstruction.

Signe Fourmy 40:44

Absolutely, when they start pushing back, and then when people start to realize I have the right to vote, and I should be able to exercise that without fear of reprisal. When I have the right to choose my job, or to move from one employer to another, these are really important things that a lot of people take for granted. And if you don’t show that sharecropping contract with your students, they have no idea. If you put it before them, they understand they’ll get it, they’ll make the connection.

Kerry Green 41:15

And if nothing else, you lay out the cognitive dissonance, you say, yes, these are the documents, what do you think about the documents? And yeah, you might have some students that it just flies over their head, and they don’t understand it, but you still expose them to it. And you don’t know when they’re gonna have that moment.

Jesse Hagopian 41:33

You know, one of the lessons that I’ve used a lot, gets the students to ask the major questions that formerly enslaved people were asking during Reconstruction. So one of the key questions was, who would control the land, and what would be done with that land? And so this lesson at the Zinn Education Project, asked students to be a delegation to Washington, DC during Reconstruction to make some demands of the government, and they get to decide what those demands are going to be. But they have to be based on the real questions that were being debated at the time. So who will control the land? Would you be willing to promise northern politicians that if they gave you land, that you would continue to grow cotton? And so they research that issue and see, what did Black people organize and demand for at that time? And what do you think you should call for? Or we asked them about what should happen to the Confederate leaders who led this treasonous assault that killed hundreds of 1,000s of Americans? What is your delegation thinks should happen to those people?

They research what some of the different positions were. They research the question who should be allowed to vote in the New South, everyone, only former slaves those who were loyal to the United States during the war. What about women who were also fighting for their right to vote, and they look at the various positions that were held at that time. These are the questions that we need to grapple with.

Today, we need students to be able to understand how those social movements were built during Reconstruction that made demands of power, because we desperately need students to be able to think critically to build a more equitable society today and employ the lessons of the past and helping them move forward.

Kerry Green 43:32

I have used Zinn Education Project in my classroom. And I find it very helpful. I praise the Zinn Education Project and it is one of my bookmarks I go to pretty frequently.

Jesse Hagopian 43:44

That’s wonderful to hear.

Michelle Manning-Scott 43:46

We’re running out of time here. But before we go, I wanted to give everyone the opportunity to throw out some contact information. For any listeners who might want to get in touch. Want more information, especially in regards to the Zinn Education Project. So whoever would like to go first,

Jesse Hagopian 44:06

People can access the Zinn Education Project, free downloadable lesson plans at zinnedproject.org or on Twitter, at Zinnedproject and on Instagram.

Signe Fourmy 44:23

Last Seen, we’re also working like Zinn [Ed Project] to develop curriculum around this period. And we have a number of lesson plans and document sets that we have posted to our website, informationwanted.org. And we’d look forward hopefully to maybe working with Zinn [Ed Project] to develop new lesson sets. We’re also trying to work with teachers we’re trying to put together teacher conferences and staff development that we can get into the classroom and put our documents in teachers hands so they can get to students hands.

Michelle Manning-Scott 44:57

Wonderful. Well this has been a really engrossing conversation. And again, I want to thank all three of you for joining us to talk about all this.

Bob Dailey 45:06

I want to add my thanks to this was really informative.

Jesse Hagopian 45:10

Thank you all so much. Appreciate it.

Signe Fourmy 45:13

Thank you.

Kerry Green 45:14

Thank you for including me.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn