On March 24, Rethinking Schools editor Jesse Hagopian spoke to historian Jeanne Theoharis about her latest book, King of the North: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Life of Struggle Outside the South.

This talk marks the fifth anniversary of the Zinn Education Project’s Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online class series, which Theoharis co-founded. Watch our 60 previous Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online classes and register for upcoming classes here.

In the excerpt below, Theoharis describes the relevance of King’s radicalism today and what we lose by the continued misuse of his legacy.

I added more resources to my teaching tool chest. One of the most meaningful pieces I will take away was the interaction between Johnnie Tillmon and Martin Luther King Jr. The ability to admit you don’t know something, and the openness to gaining more knowledge, is a profound thing.

That Coretta Scott King was a force to be reckoned with way before Martin.

Today reinforced and deepened my understanding of how Martin Luther King Jr. is used as a cudgel to attack present day activists and movements, which is deeply damaging to our students and their organizing and direct action tactics. As King said, “If our direct action tactics alienate our friends, they were never really our friends.”

I’m reflecting on the idea of King as a listener who traveled “Jim Crow America,” stayed in people’s homes, and evolved his positions based on what he learned from real people. Stories that will stick with me include King protesting the police murder of Ronald Stokes, King working with gang leaders, Jeff Fort describing King as a listener, and how Chicago thwarted school integration.

Keep on keeping on. . . this is the refreshing clean water we need to wash away all the hatred and evil that is roaming around this country!

Thank you for doing this amazing work. You are a lifesaver in a sea of misery.

Event Recording

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: I want to highlight that tonight’s event falls on the fifth anniversary of the launch of the Teach the Black Freedom Struggle series. On March 27, 2020, a project that Jeanne Theoharis conceived of and co-founded and has collaborated with to bring essential but often overlooked histories into the public conversation. I’m deeply grateful to Jeanne for reaching out to me and to the Zinn Education Project for this series, and our thanks to everybody who has helped to make this series such a wild success and helped us on this journey. We want to thank all the scholars who have participated over the years, all the educators who have participated, all the interpreters and the breakout group facilitators, everybody who has made this warm and loving and radical community possible to continue this fight for antiracist education, sometimes under very difficult circumstances. We really appreciate you all.

I also just want to say, before we begin this conversation, that Jeanne comes from a long line of people’s historians that are dedicated to shining a light on hidden histories. She recently published a powerful essay about her great grandfather, who bore witness to the 1909 Adana massacre, one of the precursors to the Armenian genocide. It was just an extraordinary story that she tells, this act of resistance from her great grandfather, known as Charles, who wrote a poem documenting the horrors he saw, inscribing Turkish words in Armenian letters. And against all odds that poem has survived to this day, passed down through the generations as a testament to memory and resilience. As someone who also has ancestors who survived the Armenian genocide, this history is deeply important to me. The struggle against historical erasure is a fight for the dignity of those stories and those whose stories have been buried or distorted. So I think that Jeanne’s work really embodies this same kind of commitment that her great grandfather began.

And her hot off the presses new book drops tomorrow, King of the North: Martin Luther King’s Life of Struggle Outside the South, and it challenges us to confront the ways that Dr. King’s radical legacy has been reshaped and misrepresented in the service of maintaining the status quo. So welcome, Jeanne, and thanks so much for being with us on this fifth anniversary.

Jeanne Theoharis: Wow. I’m feeling very moved tonight. I mean five years, and just to be together, to have this night that I launched the book, but also that we were celebrating having done this. We were talking before the call started about how people are now having questions about how do you make a freedom school, and you’re like, “We’ve got it. We know how to do it.” It’s beautiful. And it’s really both. It’s very meaningful to be together for five years. I saw people in the chat talking about how many of you have been with us for much of that, so that just feels like, wow. And then to have my book tonight, on the five year anniversary, what a blessing.

Hagopian: It’s so fitting. With that, we should jump into the new book, because it’s so great, and there are so many things I want to ask you about it. But I thought we could start with just the misuse of Dr. King’s legacy. In your book you critique how Dr. King’s radical critiques of Northern racism have largely been erased, allowing his legacy, really, to be weaponized against our movements today. You write that King is now “America’s Black friend held up and mythologized to punish activists who pushed too hard against the status quo, the ultimate gaslight.” I love that sentence. And King himself warned, “if our direct action tactics alienate our friends, they were never really our friends.” So how do you see this selective memory of King’s work being used today to suppress activism and antiracist education, and why do you think the dominant narrative continues to resist this reckoning with King’s radical legacy?

Theoharis: First, I love that quote too. I fantasize about having that quote on a shirt, because I do think, and one of the motivations of this book was the ways that King is rolled out against, I mean, we saw it from the beginning of Black Lives Matter in 2020. We’ve seen King rolled out again around the Palestine protest, this notion that he was acceptable and respectable and he did things the right way. And I think one of the crazy things is that so many of the criticisms of young people today are criticisms of King. In particular, I think one of the things that turning our gaze out of the South does is see that many of the Northern liberals who come to support the movement in the South at the same time are resisting and gaslighting movements much closer to home.

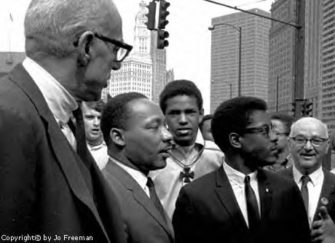

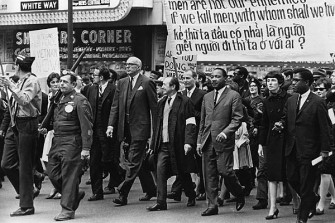

So one of the things I think we talk about often on King Day is the ways that King is misused and stripped. But I think one of the things looking at him outside of the South shows us is he’s being misused in his lifetime. There’s this kind of thing that’s happening where people will want to take pictures with him, and by 1963, 1964 these same people, when he says, “Well, let’s talk about police brutality in New York. Let’s talk about school segregation in New York.” Then they say, “You don’t belong here.” They say you are an outside agitator. They say, “You don’t know. Who are you to say this?” They say, “I’m a friend. Look, I’ve been a friend of the Southern movement.” The deflection, like all these things are happening as Dr. King is alive. And I think that looking at the North and seeing that our story of King in the North starts so much earlier than I think most of us, I think, come to this conversation, knowing some things about the radical King, right? We know that he ultimately took on the war in Vietnam. We know at the end of his life that he is working on the Poor People’s Campaign. But I think what turning our attention to the North does is to see those lines and links so much earlier, really from the beginning of his adult life. Because I think the dominant narrative is both that he turns North after 1965 but also that he gets radical at the end of his life. And again, I think when we look at him outside the South, when we see all the things that he’s doing, the movements he’s supporting, the things that they’re thinking about, both him and Coretta, we see a person who is both critiquing the limits of liberalism at home, critiquing an America that is kind of riven with segregation. Not that segregation is a regional problem, but a national problem. He’s critiquing both sides-ism and so many of the things we live with today.

Hagopian: Yes, I love that framing. And the research you did to really dig deep into it is amazing. You write that despite the avalanche of King biographies, many have failed to connect the dots with his work on the North. And you point out that most writers only begin to consider King’s involvement in the North after the Watts uprising. So what do you see as the most significant new contributions your book makes to understanding Martin Luther King Jr.? And in the process of researching and writing, what discoveries surprised you the most?

Theoharis: Well, let me start where I actually started. Where I began this project is actually almost 20 years ago in LA, and I’m working on and researching the Civil Rights Movement in LA before 1965, before the August 1965 Watts Uprising, in the decade before. And I keep finding King, and I’m just like, “Wait, wait, wait. That’s not the story. The story is that he discovers the North with Watts.” But here he is in 1962 protesting the police killing of Ron Stokes and saying, “There can be no compromise on the issue of police brutality.” This is King in LA in 1962. In 1963, he’s in LA comparing the segregation of LA to Birmingham’s at the same moment that they’re having the campaign in Birmingham. In 1964, California had a horrible proposition on the ballot. They had managed to pass a kind of modest Fair Housing Act at the end of 1963, after years of activist work. It would not have even applied to most single family homes. But still, it was a step forward. White people go crazy. White Californians go crazy and they get Proposition 14 on the ballot. King flew back and forth to California multiple times over 1964, calling this a vote for ghettos. He’s calling this one of the greatest tragedies of the 20th century. The New York Times just refers to it as a speaking tour. They just ignore it altogether. The LA Times comes out in favor of Prop 14. So this story of LA is really where this book begins, because it forces us to see these long standing movements in these cities.

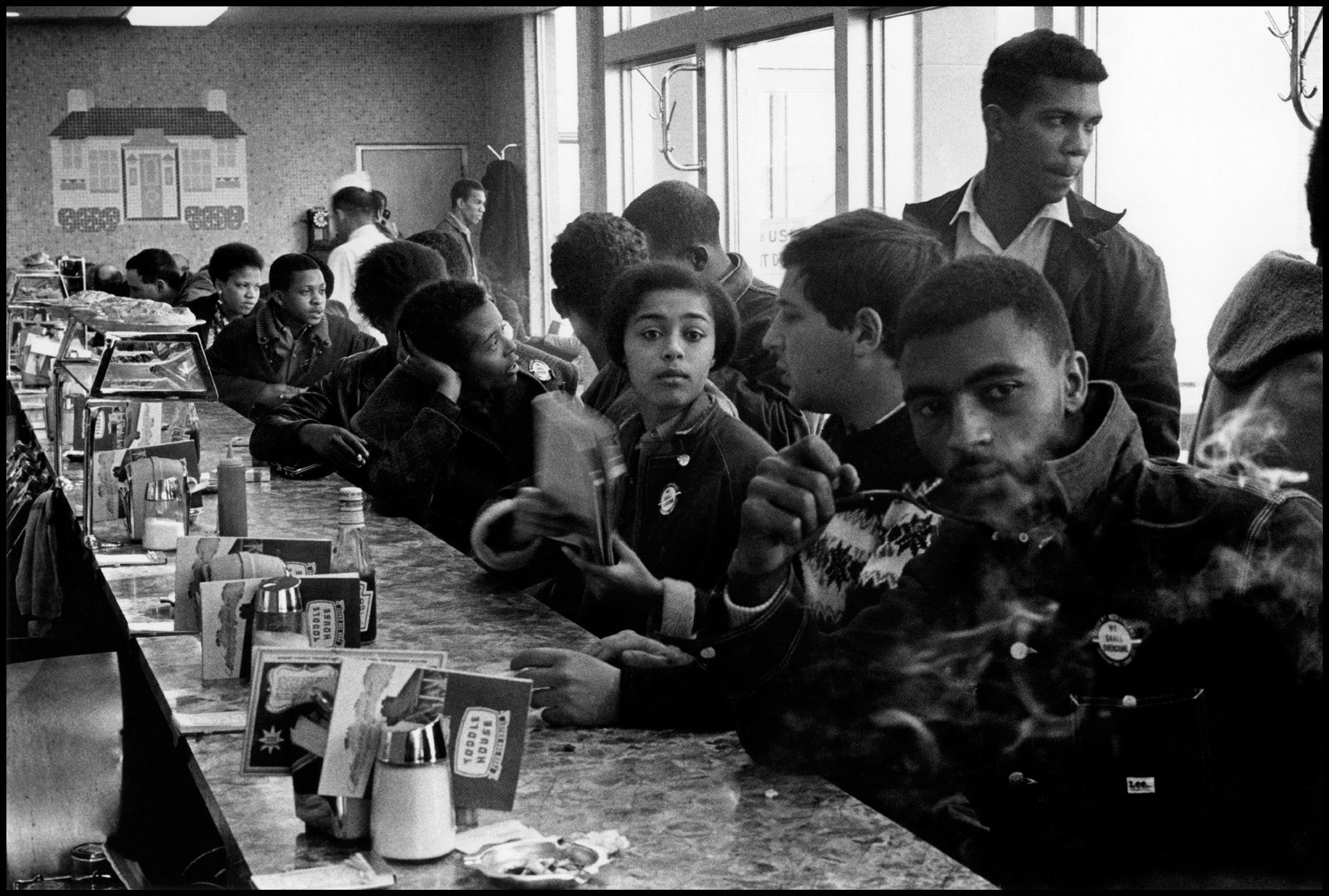

I think one of the greatest myths about the civil rights era is that Northern Black people did not go for nonviolence. And you know who it was that did not go for nonviolence? Northern white people. In terms of Northern Black people, there are massive nonviolent movements in the North, and the book really tries to chronicle some of them. Because, in part, what King is doing in these years, between 1958 and 1964, 1965, is he’s flying around, showing up for other people’s struggles — from Local 1199 strikes in 1959 in New York City, to school segregation marches in Chicago, to Prop 14’s defeat. When we look at him, we can see a kind of tapestry of struggle in this period. And yet the way that we often teach the Civil Rights Movement is still in the South. And obviously we have been doing a lot over these five years to bring scholars who are getting us out of the South, who are helping us to see the Black Freedom Struggle in many places.

But I think one of the things that King allows us to see, because he goes to so many places, because he’s a figure we’re used to teaching, because he’s a figure that’s acceptable to teach, is by seeing him in all these places we also get to see movements all around the country. But those movements are being challenged. They’re being gaslit. They’re being demonized. They’re being called communist. To talk about police brutality in the North is to be a communist. To talk about housing desegregation in the North is to be a communist. King is being picketed as a communist for talking about those things. So I think it very much changes the arc of the way we talk about the Black Freedom Struggle, but also kind of who the good guys are, right? And in some ways, and we’ve talked about this a lot over the past five years with many scholars, is this kind of easy narrative, or maybe not easy, but comfortable — that’s the word I’m looking for — this comfortable narrative that we have been given in many of the books that many of us have to teach. Which is: We go from Brown and then we have the Montgomery Bus Boycott and then we have SCLC and SNCC and their struggle, and it’s hard, but then we get the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act. It’s just a beautiful arc right now. If we take that narrative and we actually get ourselves out of the South, that narrative gets a lot less beautiful. It gets a lot less triumphant, yes, but I think it also says so much more for how we struggle today.

Hagopian: I think that brings us to understanding the widespread misconception that segregation was solely a Southern issue. You began to talk about if we look more broadly at the Civil Rights Movement, and we look at the North as well, we see that it was entrenched in the North as well. And you wrote this quote: “What if the 1964 Civil Rights Act had actually been enforced against Northern school districts and then King’s work against school segregation and housing discrimination.” Economic inequality in the North, particularly in Chicago, has often been overlooked or it’s been dismissed as a failure, but you highlight how he faced violent white resistance and how the media downplayed his Northern activism compared to the South. So can you speak about how the Northern segregation was maintained, how the resistance was organized against King when he was fighting it in Chicago and beyond, and then how the public and media perception of his activism in the North differed from those in the South?

Theoharis: We have to start with the media. And, in fact, going back to the question you asked before, there are many books on Dr. King and I think one of the things that most surprised me was how much there was to find. But, in part, that required also reading against the national media. Basically, this is the national media story of the time. I think if we were to talk about Malcolm X tonight we would know that we would have to look at the national media as a potentially hostile source around how they would be covering Malcolm X, and if, when we talked about that, we’ve had people to talk about the Black Panther Party, similarly, but with King there has been a tendency in many books to take the national media as a trusted source. In part because by the early 1960s, we do see some of those national media outlets being willing to do a different kind of reporting in terms of the South, and we do see some very courageous reporters go down, and they are not taking Southern leaders’, political leaders’, words at face value. They are doing much more extensive stories about the movement that is emerging in the South at the same time.

The ways they’re covering the North is not that it’s a movement, it’s these individual disruptive protests. It’s not a noble movement, and we don’t see the same questioning of Northern public officials. So when you have a Northern public official say, “We’re not segregating,” then the New York Times says they’re not segregating, and they tend to take a much more . . . We’ve talked about this when we had Brian Jones talking about New York, when you look at how the New York Times covers the New York City School boycott, right? We may remember this unreasonable, violent, reckless, adult encouraged truancy, dangerous, right? All these kinds of words at the same time, these are not the words that they’re covering, for instance, the Birmingham movement. One of the first tasks was to try to get out from underneath and figure out how this story had gotten constructed and why, and part of that leads to the media.

Both Martin and Coretta are critical of the ways of the media. King will talk about it like that, “We’re being bombarded by half truths.” Coretta will say, “The media never understood Martin.” There’s a story that Harry Belafonte gets super angry at a New York Times reporter at King’s funeral for [because] there he is sad at the funeral and then contributing to the climate that produced the funeral. So I think part of what the book reckons with is the ways that the media could have been doing and kind of really moved on issues of Southern segregation at the same time, not in the North. To give you another example: That question that you quoted me saying, like, what would it mean if Johnson had been willing to enforce the Civil Rights Act in the North? So, one of the things that we know about the 1964 Civil Rights Act is that it ties federal funding to school desegregation, and what that produced, even though we’re ten years after Brown, some of the first real movement around school desegregation, particularly in the South.

What we also see is we have massive movements from cities — from LA to Chicago to New York — around school desegregation. Chicago activists in particular, and we know Chicago there’s that great documentary on the 1963 school boycott in Chicago. There’s a really robust movement in Chicago challenging segregated schools, challenging the fact that Chicago schools serving Black students are so overcrowded that they’ve gone to a double session day, which means that Black students are getting a half school day because they have one group of students going in the morning and one group of students going in the afternoon. And that’s a pattern that Northern public officials have moved to in many cities, but they’re doing this in Chicago as well. So Chicago activists say, “Hey, we have a Civil Rights Act that says you can’t segregate and get federal money.” So they filed suit with the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, which is what it was called at the time. And HEW comes and they ask lots of questions of the Chicago Board of Ed. What kind of class size, teachers, etcetera. And the Chicago Board of Ed refuses to answer. So in October 1965 they announced that they are going to hold $32 million in federal funding because Chicago schools are in non-compliance. And white Chicagoans, Chicago congressmen who voted for the Civil Rights Act, they go nuts. Mayor Daley gets on a plane, confronts Johnson, and less than a week later, Johnson orders HEW to disperse the money And enforcement of the Civil Rights Act against Chicago and effectively against other Northern districts is basically over.

So we have this moment where we can see a possibility. And King says multiple times, if we’d had a movement like the movement in Chicago against Chicago segregated schools in other places in the country, we would have produced incredible change. One of the things he’s grappling with pre-1965, before they make the decision to join the Chicago campaign, SCLC does this incredibly robust movement, and then this incredible devastation in October 1965, where Johnson’s like, “No enforcement.” I think that really changes. It both shows us what’s possible — what if there were actual consequences for continuing school segregation that many of our schools live with today? And then also people that we think of as some of the allies, like Lyndon Johnson, outside the South Johnson is not going to disrupt Northern Democrats, so I think it gives us a sense of possibility, but also a more sobering, more beautiful, and terrible history, if you will.

Hagopian: Well said, no doubt. I appreciate that framework so much. I’ve got one more question for you before we move to breakout rooms. I think I’m going to ask you about King’s politics around gender, and his leadership style, because I was really fascinated by this part of your book. I think it adds a lot to our understanding of who he was. And King’s understanding of gender and economic justice evolved over time, as you showed, particularly through his engagement with welfare rights and the welfare rights movement. That has a lot to do with the influence of Coretta Scott King. At first he shared concerns that welfare might undermine Black men’s dignity. Then you show how activists like [Johnnie] Tillmon changed him. You quote him, I love this, you quote Tillmon telling him, “Dr. King, if you don’t know, you should say you don’t know.” If you don’t know, you should just say it, right? And rather than dismissing this critique, I found this fascinating. Rather than just dismissing this critique, King actually admitted he had to learn. And over time, he came to see welfare as a right and really central to his work for economic justice. So, we have to talk about King’s gender politics, and also, what does his willingness to listen and learn from Tillmon and from Coretta Scott King tell us about his leadership style and his capacity for growth?

Theoharis: One of Dr. King’s greatest gifts is his ability to grow and listen. It is also a place of tremendous personal pain. Coretta Scott King will talk about that. There is no one harder on Dr. King than Dr. King himself. He constantly questions himself. He takes criticisms into himself. It can be, in some moments, very devastating personally, but it also produces his ability to keep taking . . . Well, just to step back for a sec, part of what Dr. King is doing, he travels six million miles across the United States, going all these different places, and he’s learning from people. One of the things that we want to remember is that this is not just a Jim Crow South, it’s Jim Crow America. Which means that Dr. King, like most hotels don’t serve Black people in the North as well as in the South. So he’s staying with people, he’s learning, he’s changing, people are pushing him.

Like you’re saying with welfare, like many issues, he learns, he takes that politics into him, into the ways that they’re organizing, and then adds to it. We see welfare being one of the issues that the Chicago movement was pushing for in 1966, and then we see that as part of the Poor People’s Campaign. Just to give you another example, as I mentioned, in 1959, he started working with Union 1199. People on the call may know 1199 as the health and hospital workers union. They were organizing the poorest hospital workers. At this point, it’s an interracial union, but they’re really a model. They’re King’s favorite union. It’s the only union Malcolm speaks to, in part because of this radical interracialism. And through this work, supporting this strike of the lowest paid hospital workers — which are Black women and Puerto Rican women who are orderlies, who are doing split shifts at these hospitals, coming in the morning, coming in at night. King says the wages are so low you can’t even call them wages. But similar to Rosa Parks., Dr. King is not super sassy.

Anyways, in the process of doing this work, he comes to see . . . because in New York you see the connections between the ways Puerto Ricans are being treated and African Americans. So we see Dr. King start to see the importance of incorporating Puerto Ricans into and thinking about Puerto Ricans. One of the things I never knew until doing this research is that they recruited Puerto Rican organizers that they knew through 1199. An organizer, for instance, by the name of Gilberto Gerena Valentín, to come down to Atlanta to help them organize for the March on Washington. So thousands, if not tens of thousands, of Puerto Ricans actually attend the March on Washington. Again, that gets us to the media. It’s front page news in El Diario, which is the biggest Spanish language newspaper at the time. But again, it’s completely really missed in the ways that we imagine. At the March on Washington, people are carrying Puerto Rican flags, and they’re singing the Puerto Rican anthem. King is taking in through these experiences, both expanding his politics and then also I think his other gift is the double down. He doubles down and doubles down. And that means his politics are getting even more fierce. That’s, I think, when we see the way he’s adding economic welfare rights and economic justice. But again, for King, this is not moving from race to class. It’s all of it, right? And so it’s more and more and more.

Hagopian: Yeah, there’s so much there. I had no idea about this Puerto Rican history part of it.

Theoharis?: I know! Then I was looking, wondering if other people wrote about this. Then I go to Will Jones’s great book March on Washington, and I’m like, wait.

Hagopian: Well, thank you for doing this research and just giving us such a much better understanding of who he was and how he developed his politics. It’s such a brilliant book. Everybody needs to get it to effectively teach about him.

[breakout rooms]

Hagopian: Alright, welcome back, everyone. I want to jump right into some of my favorite stuff in the book. I was learning about Coretta Scott King, who has been far too obscured in the shadow of King. But you correct that in some really important ways. Throughout the book, you highlight Coretta Scott King not just as Dr. King’s partner but as a formidable activist in her own right. You write that, “Coretta understood as well the urgency of tackling the triple evils of poverty, racism and war and contributed much to shaping MLK’s understanding of issues like welfare rights and deepening his critique of capitalism.” So in what ways did Coretta shape King’s political evolution and how does the book push back against the tendency to sideline her in the movement, like is so often done with Black women in general? How do you think Coretta shaped his political development?

Theoharis: Well, one of my favorite quotes from Coretta Scott King is she says, “I’m made to sound like an attachment to a vacuum cleaner, right? First the wife of Martin, then the widow.” And she says, “You know, I was happy to be those things, but not only those things.” So I think where we need to begin with her is who she is. Even before they meet, she is more of a political activist when they meet. Coretta Scott King grew up in Alabama to a very proud political family. Her family owns their land. Her dad delivers lumber. Those things draw the anger of white people in their community. Their house is bombed, and so part of what she learns growing up is . . . people will talk about Coretta Scott King as being beyond steel and just this ability to move in the midst of frightening situations. She and her sister become some of the first Black students to go to Antioch in decades. Antioch is probably one of the most liberal colleges in the nation at this point. It’s in Ohio. At Antioch, it’s both an incredible opening for Coretta Scott King, she gets involved in all sorts of political work, both around racial inequality in the United States but also anti-Cold War.

She becomes involved with the Progressive Party. The Progressive Party in 1948 was running a third party challenge to Truman on issues both of segregation at home and Cold War militarism abroad. So Coretta Scott King becomes a student delegate for the Progressive Party. One of 150 Black people that went to the Progressive Party convention in 1948, she met Paul Robeson through this work, she met Bayard Rustin. She had heard Bayard Rustin actually in high school. Just to pause with that, before she meets Martin Luther King, she’s met Paul Robeson, and Paul Robeson is her hero. Coretta Scott King majors in music and education at Antioch. But Antioch is also an experience like Martin will have in graduate school in the North of deep disillusionment with both Northern segregation and the limits of Northern liberalism. Because, as we all know, when you’re an education major, you have to student teach, except that Yellow Springs, Ohio, which is where Antioch is located, won’t let her student teach. Antioch sides with Yellow Springs and says to her, “You should go student teach over in this Black town, Xenia.” And Coretta Scott King says, “No, I didn’t pay for that.” She’s fierce from the jump. She tries to get those very radical students at Antioch, classmates, to join her in this protest, and they refuse because they’re worried about their own placement. So I think we have this experience, and Martin will have a similar experience when he’s at Crozier. He’s thrown out of a bar in New Jersey with friends at gunpoint. The bar owner throws him out at gunpoint, but when they think about filing an anti-discrimination suit, three white students who had also witnessed the segregation of the bar refused to testify. So both of them have these experiences of both Northern segregation but also of allies disappearing under pressure.

She then moves to Boston to attend the New England Conservatory of Music. She is introduced to Martin Luther King through a friend. They talk about racism and capitalism on their first date. He is wowed. He has never, I think, met a woman like her. At the end of their first date, he’s like, “You have everything I want in a woman. You’re beautiful, you’re smart.” All these things. She’s like, “You don’t know me.” One of the funny things about their courtship is the ways she’s not letting him get away with it. I think some of the charm that other people might have let him get away with, she calls it “intellectual jive”. I love that phrase. So he’s having to really bring his A game. And I think one of the things they find in each other is this determination to fight injustice in the world, but also a faith.

One of the other interesting things I discovered is that she’s having to do live-in domestic work to be able to afford to go to New England Conservatory. She’s not going to church. She’s living in Beacon Hill. If anybody knows Boston and Beacon Hill in the 1950s, there are no Black people. So she’s not going to church. Her friend tells King she’s not going to church. He doesn’t care. He doesn’t want a fundamentalist. But interestingly, she brings a lived faith that I think Dr. King — we haven’t talked about this — but when he goes to college at Morehouse he doesn’t want to be a minister. His dad’s version of a Baptist ministry is too emotional; it’s not grounded in the world enough. It’s not fighting injustice in the world enough. And through some of his mentors at Morehouse and then at Crozier he comes to see a much more politically engaged ministry. But I think the final thing is really meeting Coretta Scott King and seeing the ways that to her being a Christian is what you do in the world, period. I think that also what they find in each other is that . . . So, I mean the Progressive Party, racism, poverty, militarism. I mean, she’s got that. I mean, I’m not saying she doesn’t change, they don’t grow, but those are ideas that she brings to their partnership.

She also will become the family leader on peace and anti-colonialism. She went to Geneva in 1962 to press the United States and the USSR with the Women Strike for Peace around nuclear disarmament. In 1963 she marched on the UN around nuclear disarmament and what she sees as their responsibility when Martin gets the Nobel Prize is that they need to come out against Vietnam. And she does so. In 1965 she was doing all sorts of work around the country. She is the only woman to speak at a big rally at Madison Square Garden in June 1965. A reporter asked King, “Did you educate her?” And he says, “She educated me.” So I think it also flips it to understand that in many ways, Coretta Scott King, and both of them, talk about how she’s the family leader, or she’s the person doing the work around peace and global justice, and he’s following her lead. Many people are influencing Dr. King, but I think perhaps his most influential advisor is Coretta Scott King, and I think we’ve really missed that.

Hagopian: Oh yes, absolutely. I have just a whole new appreciation for who King was. We just have a minute. So maybe in a minute, could you sum up some final thoughts, including, I think one part I really loved is you challenging the way he’s used to respectability politics, and you point out that he actually worked with gang members and learned from them, and that this is another side of King that’s hidden, and anything else you want to just highlight about him before we go? I think we really need part two of this conversation. We could think about doing that next year based on this book. And I bet a lot of you in the audience would love that. Wouldn’t you love to hear part two of this discussion?

Theoharis: One of the things that I discovered in doing this work is what Jesse just alluded to, which is that King does all of this work in Chicago with gang members. I think if you knew that he worked with gang members, the way that we’ve been given is some combination of pull your pants up, say no to violence, sort of respectability politics. And when you actually listen to what those gang members and gang leaders say. I mean, he saw them as leaders, and he looked to them as leaders. He looked to them as people who understood what their communities were facing. He’s engaging them in serious conversation.

One of the things I also think we don’t really understand, is that King was also a listener. Probably my favorite description of King as a listener comes from the head of the Black P. Stone Nation, Jeff Fort. Fort talks about how King never interrupted you, and that people would talk way too fast around King because they’d be so nervous. If he asks you a question you would rush and then he’d be like, “It’s okay, we have time, slow down.” And he would call all these young men “Doc,” which, as many of you know, is often a way that ministers, particularly Baptist ministers, talk to each other. So he would use this affectionate term with these young men. And they came to protect him, and they were part of the open housing marches in Chicago. In the summer of 1966 they went to the James Meredith march in Mississippi, in 1966 they went to the Poor People’s Campaign. So this politicization, some of which we often associate with Fred Hampton’s Rainbow Coalition, actually begins, and Hampton talks about this with some of the work that King had started in 1966, both with Puerto Ricans in Chicago and also with various gangs.

Hagopian: Wow. I can’t thank you enough for all the research you did and helping us better understand the Black Freedom Struggle and King’s contribution to it. What a wonderful conversation tonight. Thank you all for being here.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect, please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

Here are many of the lessons, books, and other resources recommended by the presenters and participants:

Lessons and Curriculum

|

A Revolution of Values by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Hidden in Plain Sight: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Radical Vision by Craig Gordon, Urban Dreams, and the Martin Luther King Jr. Papers Project COINTELPRO: Teaching the FBI’s War on the Black Freedom Movement by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca Stepping into Selma: Voting Rights History and Legacy Today by Teaching for Change ‘We Had Set Ourselves Free’: Lessons on the Civil Rights Movement by Doug Sherman Teaching A People’s History of the March on Washington by Jessica Lovaas and Adam Sanchez The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks Teaching Guide by the Zinn Education Project “Intolerable Conditions”: Teaching About Northern Racism Through Rosa Parks’s Detroit by Say Burgin, Jeanne Theoharis, and Ursula Wolfe-Rocca The Rebellious Lives of Mrs. Rosa Parks by Bill Bigelow Teaching SNCC: The Organization at the Heart of the Civil Rights Revolution by Adam Sanchez |

Books

Articles

|

Learning From the Courage of the Civil Rights Movement by Jeanne Theoharis (Jacobin) MLK in the North: The Civil Rights Leader Understood That Racism and Segregation Were National Problems by Jeanne Theoharis (Teen Vogue) W. E. B. Du Bois to Coretta Scott King: The Untold History of the Movement to Ban the Bomb by Vincent Intondi (an If We Knew Our History article) Challenging Ourselves: Martin Luther King, the Movement, and Its Lessons for Today by Charles E. Cobb |

Additional Resources

|

People’s Historians Online: Rethinking Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. a 2020 Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online class with Jeanne Theoharis and Jesse Hagopian Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.: “Beyond Vietnam” film clip from Voices of a People’s History |

This Day In History

The dates below come from our This Day in People’s History collection, which contains hundreds of entries all searchable by date, state, theme, and keywords.

|

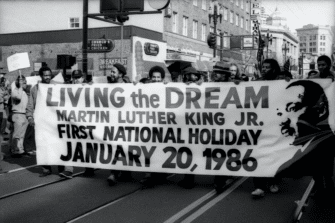

April 14, 1909: Adana Massacre March 26, 1964: Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X March 25, 1965: Last Selma March June 11, 1965: Chicago School Boycott April 4, 1967: Martin Luther King Jr. Delivers “Beyond Vietnam” Speech April 30, 1967: “Why I Am Opposed to the War in Vietnam” Speech Feb. 12, 1968: Sanitation Workers Strike in Memphis March 14, 1968: King Speaks About the “Other America” in the North March 22, 1968: March for Justice and Jobs April 4, 1968: Martin Luther King Jr. Assassinated May 12, 1968: The Poor People’s Campaign Began Jan. 20, 1986: First National Martin Luther King Jr. Holiday |

Participant Reflections

With nearly 160 attendees present, the conversation and chat was lively, engaging, and full of history, teaching ideas, and more. Polls showed participants included 40 percent K–12 teachers, 21 percent teacher educators, 7 percent historians, and more.

Here are more comments that participants shared in their end-of-session evaluation:

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

I think one of the most important things that I learned today was the degree of organizing that Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. did in the North, years before he was recognized for it. Also, his organizing with gangs and the relationship of protection that they gave to Dr. King was eye-opening.

The role of Coretta Scott King in the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. and the Civil Rights Movement.

The idea I liked most today was Dr. King’s sentiment that if our friends are alienated by our direct action tactics, then maybe they aren’t our friends.

Coretta Scott King met Bayard Rustin and Paul Robeson before she met King. Also that King was in alliance with Puerto Ricans to organize the March on Washington.

The limits of Northern liberalism.

That the mainstream media doesn’t seem to have changed much from the 1960s to today.

There are so many stories that have not been shared about Dr. King. I especially appreciate learning more about Coretta Scott King’s activism and her influence on Dr. King. I also appreciated hearing about Dr. King’s inclusion of Puerto Rican healthcare workers as he championed the rights of healthcare workers to form unions.

The North is truly an example of how the U.S. learned how to hide or handle its racism: just pretend it’s not happening by making sure you never explicitly say you’re segregating, and never report on your violence. If you do these things, clearly you’re not racist and the South remains the bad guy.

That we have to hit the streets and demand our human rights.

What will you do with what you learned?

I was quite struck by the phrase, “We see Dr. Kind as ‘acceptable’ to teach” — which in my mind provides us with an (under the radar) opportunity to teach his life and his work more deeply, to provide students with deeper analyses of how our northern cities (where I work) were not, and are still not as desegregated, equitable, and inclusive as we are taught to believe. Students can see this in our own community and connecting Dr. King’s work for economic justice, education and access in our own community would be very powerful.

I’m so excited to teach Martin Luther King Jr. in so much more depth to my second grade students, sharing a more well-rounded picture of who he was and what he stood for.

I will incorporate the book into my classroom library and use these resources to influence my summer school English curriculum. I’d like to incorporate this book by having students read and discuss.

I would love to find ways to bring the true history of King in the North, as well as Jim Crow America (rather than Jim Crow South) into elementary classrooms. . . . I bet almost every elementary teacher in the North does read-alouds in January or February about civil rights, MLK, and Rosa Parks. We need to get elementary teachers to also think critically about the books they use (and the narrow and inaccurate narrative they tell), to share lesson plans with each other, etc.

I write curriculum for adult English language learners and the more I know, the more clearly I can create materials that address the Black Freedom Struggle. These sessions are incredibly helpful to me in making sure I am staying on top of factual information about American history from the Black perspective, centering Black voices and the vast role played by Black Americans in U.S. history.

I would like to bring in more materials to show how King was radical and perhaps ways that his views aligned with those of Malcolm X.

I want to continue to learn more and gain insight from multiple perspectives. What we learned in school about Dr. King’s life and his impact on the world is narrow and one-dimensional. His activism in the areas of healthcare, poverty, and anti-war efforts have had a greater impact on our modern society than I initially understood. If nothing else, I want to model lifelong learning, provide students with access to multiple perspectives, promote empathy and understanding of our common humanity, and empower students to contribute to the greater good and become agents of positive change.

How was the format for the class?

Great all around.

This is the only Zoom workshop I’ve ever been in where I like the breakout rooms. Please, keep that up.

Loved the format, especially the breakout room. I got to virtually meet Judy Richardson!

All was very high-quality and I deeply appreciated such an extremely valuable discussion and learning opportunity — thank you so much!

Presenters

Jeanne Theoharis is a distinguished professor at Brooklyn College. She is the author or co-author of numerous books and articles on the Civil Rights and Black Power movements and the politics of race and education. Her books include the award-winning titles The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks and A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History. Theoharis co-founded the Teach the Black Freedom Struggle class series with the Zinn Education Project and invited our staff to collaborate on a teaching guide for The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks book and film. She recently wrote a piece with Robert Artinian on her family history, “God cried”: Charles’ “destan” on the 110th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, in Armenian Weekly.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing, author of Teach Truth: The Struggle for Antiracist Education, and serves on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn