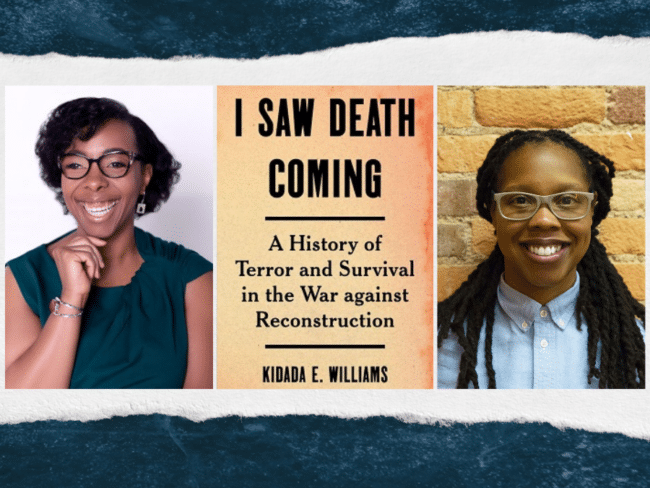

On March 20, 2023, historian Kidada Williams joined Prentiss Charney Fellow Jessica Rucker to discuss her latest book, I Saw Death Coming: A History of Terror and Survival in the War Against Reconstruction, a breakthrough account of the era that transports readers into the daily existence of formerly enslaved people and the white supremacist terror they faced after emancipation.

Audiogram

In this audiogram, historian Kidada Williams discusses the significance of bearing witness to the injustice and violence of white supremacy during the Reconstruction era.

Participants shared what they learned and additional reflections on the session:

We covered so much that I need time to process, but what immediately stands out is how important it is to research our own ancestry, collect stories of our elders, and document and leave our own stories and records!

Bearing witness to the violence was critical to African-American sense of dignity and self; Black folks have documented their experiences and we need to have a nuanced and complex understanding of violence so that we can understand resistance.

“Imprecision is an act of erasure.” I appreciated learning about the testimonies that highlight the heart of the freedom movement and “who failed to do what,” underscoring the importance of teaching the truth.

The story of Eliza Lyons was very powerful. Also the idea that this evidence of trauma from Reconstruction has been sitting in the sources, but it takes an open mind and a new lens of studying history to be able to look at the evidence and frame it in a way that makes sense to a modern audience with a modern lens of studying the effects of trauma.

The need for historians to connect with K–12 teachers, to not simply write and produce historical accounts but to partner with teachers to share those stories. Our group discussed teaching from the primary sources based on Dr. Williams’ talk. Also the idea that Black education has not always happened in the classroom and we need to understand that and support both alternative learning spaces like the home/community and the classroom.

Whew, everything was quotable! I was struck by the talking points related to white supremacy and what violence seeks to achieve. Also, how they have taken sides with teaching white supremacist lies — we will not be distracted!

Today’s event was passionate, informative, and empowering. I am honored to have had the chance to listen in, get some insight into Dr. Williams’ methodologies, and thoughts about what and how to position our teaching and learning.

So much gratitude for you all, this programming, and to be part of this learning community.

Event Recording

Recording of the full session, except for the breakout rooms.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: We have a wonderful conversation that I don’t want to delay us getting into, so I will jump right in with a welcome to everybody. On behalf of the Zinn Education Project, we are very excited for this discussion with Dr. Kidada Williams. My name is Jesse Hagopian, I work with the Zinn Education Project, and I’m an editor for Rethinking Schools. Some of you are joining us here for the first time, and some of you have participated since we launched this series. I really think it’s a gift to be with you all this evening, to share this time, and I thank you for being in virtual community with us. We have members here from Teaching for Black Lives study groups — if you’re in one of those groups, please add T4BL after your name. That will be great.

Also, I wanted to let everyone know that today’s class is hosted by the Zinn Education Project, which is coordinated by Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change as part of the Teaching for Black Lives Campaign. And the Zinn Education Project offers free downloadable people’s history lessons. I bet a lot of you have used them; they got me through teaching a lot of different subjects, and it’s been a really important resource for my own classroom and I bet for many of you in middle school and high school. We have free downloadable lessons at the Zinn Education Project, including lessons and a report on Reconstruction that I’d highly recommend you all check out. We are fortunate this evening to have ASL interpretation provided by Krystal Butler and Kenya Colbert.

Thank you both for being with us this evening. Before we begin this conversation, we want to find out who you all are, and go through our plans for our time together. So, we’re posting a quick poll to find out how many teachers, educators, librarians, teacher educators, historians, parents, students, and others are with us in the room. So, there’s the poll that just popped up. Many of you might have multiple roles. If that’s the case, just pick a primary one. We’ll do a short evaluation at the end of the whole session, and in about a week we will share the full recording of this session and all the resources that you dropped in the chat. So, keep those resources coming to help us all better teach the Reconstruction era and the Black Freedom Struggle.

You can also tweet about what you’re learning as you go and invite others to learn about this incredible monthly series that we’ve developed. So looks like our results are in from the poll, we have 48% K–12 teachers. We don’t have any students yet; I hope some students drop in with us this evening. We have 8% family members, 11% teacher educators, 8% historians, 1% librarians, 25% of the rest of you all thanks for being with us this evening. So after about 25 minutes we are going to pause the conversation between Jessica Rucker and Kidada Williams, and at that point you all will get a chance to meet each other in small groups and share your thoughts about the discussion so far, and how you might apply it to your own classroom.

With that, I’m happy to welcome Jessica A. Rucker to conduct today’s conversation. Jessica is a former high school teacher in D.C., a graduate student in the Department of American Studies at the University of Maryland, College Park, and she is a Prentice Charney fellow, and just a dope all around person that I love to collaborate with. We had a chance to write some of the curriculum together for the Rosa Parks documentary and that was a special experience. So I’m really glad that you’re getting to conduct this conversation this evening, Jessica. I’m also happy to welcome back to our series, once again, the great Kidada E. Williams, author of I Saw Death Coming: A History of Terror and Survival in the War Against Reconstruction and also the book They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonies of Racial Violence From Emancipation to World War I. She is also the producer and host of the amazing podcast Seizing Freedom. If y’all haven’t listened to that yet, you’re really missing out on a great tool to educate yourself and your students. So welcome both of you, thanks for being with us.

Jessica Rucker: Yes, Jesse, thank you so much, I’m so grateful to be here. But first, before we get into this conversation for the evening, I also want to welcome the benevolent ancestors, because they are definitely here, and all through these pages. And I wanted to acknowledge that my family is here, like literally family of origin, friends are here, my grandmother is also here with us.

Let’s go ahead and get started. I was excited to see that of the warriors that are here, 48% are teachers. I’m going to use the language of warriors because, believe it or not, your war has been declared on us. Not only has war been waged on our histories and our freedoms, but now there’s a war on how and when, or whether or not we get a chance to teach the history of our freedoms. So Dr. Williams, in your experience, tell us a little bit about how the era of Reconstruction is either represented or depicted in K–12 curriculum or post-secondary curriculum. Then I would love to hear a little bit about how your book intervenes.

Kidada Williams: Okay, first, I want to thank everyone, all of the organizers for the work you did bringing us together and everyone for being here. I’m so delighted to be in conversation with Jessica and all of you.

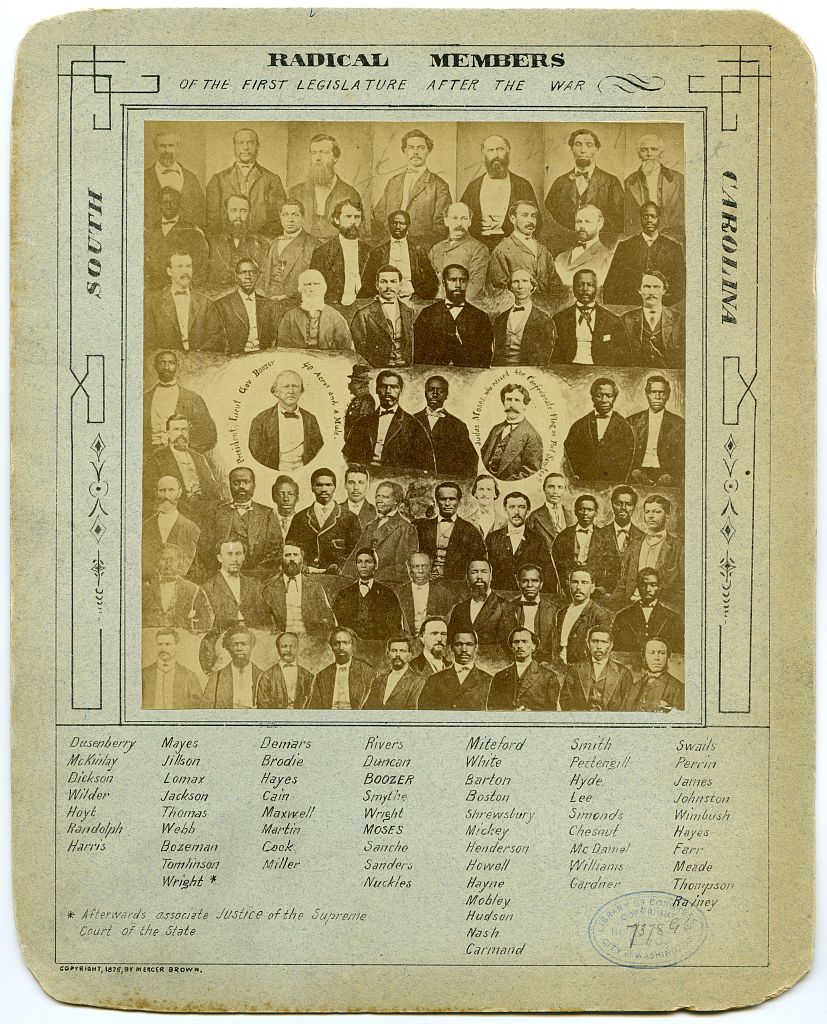

So, what I’ll say about Reconstruction is that it’s either not talked about at all, or it’s given really short shrift in comparison to, say, the American Revolution, the Civil War, or the Second World War. And so when teachers cover it, they often focus on this top down history. It’s only about what’s happening in Washington D.C., the fights between the President and Congress. Then what they do is, they sort of wrap it in this nice, neat bow of Reconstruction just failing. Now, they rarely say who failed to do what and why and how. And then that’s like the end of it, and then they move on because there’s all this other history to cover. So what I wanted to do with I Saw Death Coming was to slow that narrative down, and to really focus our attention on African Americans who were at the center of this freedom movement. I wanted to do that, because a lot of what happens in Reconstruction and emancipation, the heart of it isn’t happening in Washington D.C., it’s actually happening in like these little villages, like Desotoville, Alabama, these sorts of communities, miles outside of Spartanburg, South Carolina. That’s where this freedom movement takes place and that’s also where the war that’s waged on freedom occurs. So I wanted to center African American survivors in that story, because when we understand Reconstruction from their perspectives we have a much better sense of what actually happened and why. I think that it’s another puzzle piece that brings what happened into view in a way that has been missed in the stories that we’ve been told and in a lot of the scholarship.

Rucker: I agree. I love this analogy of a puzzle piece, because literally trying to piece together history without seeing the full picture has been very challenging for me both as a student of history. A former history co-teacher, one of my good friends, Barry, who’s on the line actually, [with him] was one of the first times I remember in a public school setting really teaching students about Reconstruction. But what I’m curious about in terms of those puzzle pieces, how did you use primary sources to write this book? Like how are those the pieces of the puzzle that needed to be put together? Then, in addition to telling us about the sources, I would love you to share something about how you read the sources, because reading as a historian is very, very important. Then say a little bit about why these sources are important to our understanding of Reconstruction, which you started to talk about — the power of Reconstruction from the perspective of the people who lived it, not the people who were pontificating about it down the street from where I live.

Williams: So, I use African Americans affidavits to Freedmen’s Bureau agents, their testimonies before Congress, letters and correspondence they wrote other officials, reports they gave to newspapers, and even some of their testimonies before Congress at some of the Southern klan trials. And lastly, I used the WPA Freedom Narratives. Now what those stories do, or what those accounts, those specific sources, give us, is an understanding of what was happening on the front lines of freedom. Again, not in a comfortable spaces, in Washington D.C., not necessarily those places in the north, but on the ground where this war against freedom was being waged. So these are the sources. I won’t purport to have discovered some new sources, these sources have been available for 150 years, they’ve been right there.

Historians are well aware of these sources, and they’ve been using them, but using them in a very select, or I would say narrow way. Historians go in looking for the election violence and that’s essentially all they really talk about. But when you go into the sources, and you read them more closely, what you see is that there’s a lot more than election violence going on. What witnesses are also saying is that losing the vote is the least of what happened to them. That’s not to say that losing the vote doesn’t matter, but what they’re also articulating is that the loss of loved ones — the loss of kin, of children, of husbands and wives — to this violence mattered more than the vote. And I think that that’s a story that often gets missed in the ways that we’ve been examining these records.

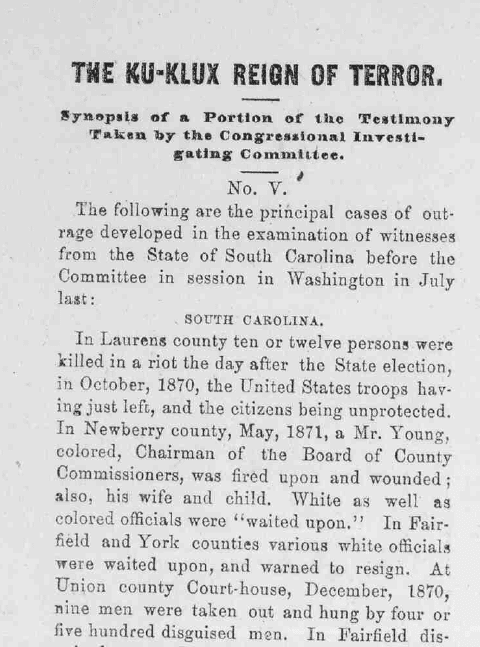

So what I tried to do was to first do a close textual reading of other sources to try to figure out and look for the testimonies. I think it’s important to understand what’s happening. African Americans are testifying before Congress. It’s not as though they’re just writing a letter and they can say whatever they want to say; they’re getting peppered with questions. What’s interesting in their accounts is how they are trying to stand their ground, if you will, to retain control of the narrative to try to make sure that lawmakers understand exactly what happened to them. They’re pushing back against efforts to trivialize what happened to them. They’re pushing back against distortions, accusations that they started it — that if Black people just behaved there wouldn’t be violence, or there wasn’t any violence at all — they come forward to say the names of their slain kin. They do all of these things. The records are so full of that.

They’re also really full of what I think is the sort of nitty gritty detail of freedom making. You can see all of the things African Americans managed to accomplish in that short five or six years from emancipation until the time they were attacked, or when they testified about what happened to them. The last thing I did, in terms of interpreting the sources, was try to use the frame of trauma, and trauma studies — all of this sort of rich research that we now have that give us a better understanding of traumatic injury — to try to read for survivors’ articulations of the impact of this violence on their bodies, their minds, and their spirits. And I think that matters, because even though they didn’t have the language of trauma that we have today, they understood that they were completely changed, that they and people in their family were completely changed by what happened. I think that’s why you see this sort of reframe: I’ll never get over it, she’ll never get over it, we’ll never be over this. And again, these are parts of the story of Reconstruction that I think have been missed, and I wanted to sit with them and encourage readers to sit with them, too.

Rucker: Yeah, and I really want to express gratitude for your interpretation, because you said a few very compelling things just now, but also in the text — which is that these are archives, these are historical records that have existed. What’s different are our frames and our lenses. It’s almost like reading your book. It’s like going to a historical optometrist and now I can see my own cultural ancestors very differently. So for this, I found your book very compelling, and one of the reasons is the way in which you censored the voices of survivors. I want to talk about that because you also are very precise with your language when you name it the war against freedom, the war against Reconstruction. So let’s talk a little bit about those who courageously and strategically testified and told their stories. I’m really interested if you don’t mind zeroing in, for example, on Eliza Lyons’ story, or maybe even a story connected to the Exoduster Movement, because I was like what! I could hear Bob Marley’s “movement of jah people.” I didn’t know there was an Exoduster Movement; so give us a story.

Williams: I’ll go with the Eliza Lyons story. Eliza and her husband, Abe Lyons, they sprint into freedom. So they’re lined up on the starting blocks, right there ready to go. They’ve been thinking about freedom for all of their remembered lives, and by 1870 they are making the most of it. They’re living on their own homestead, they’re in Choctaw County. Abe is a blacksmith; Eliza keeps house, she has retreated from plantation work. She only works on the plantation as necessary when they want to earn a little bit of extra money. They’ve got a horde of hogs, they have saved $600, all of their children are in school. So they are making the most of freedom.

And in 1871, they’re attacked by vigilantes who are part of this larger freedom-denying movement that was unfolding in these white southern efforts to overthrow Reconstruction. In this attack on their home — these are like home invasions — they’re surrounded, they rush in, they gab Abe and drag him out, and they take him away up to a hill and they kill him. Then they come back to the house and Eliza was pretty sure they were going to try to kill her, so she managed to gather the children — but her son has fled, probably to go get help. So she’s in this sort of paralyzed position, like she can’t really leave without knowing where he is, but if she stays she and her two younger daughters are going to be in danger. So they flee into the woods and the men destroy their home.

Afterward, Eliza bravely testifies, bravely reports it to local authorities. So she is afraid, but she’s ready to report it and to go through the process of what she hopes will be a trial. We don’t know what spooks her, but she flees Choctaw County, her and the children with only the things that they can carry. She makes it to Demopolis, where she thinks they might be safe and where she testifies. Her testimony reveals just how truly devastating this violence was. The family, they picked themselves up from slavery, they did everything they were supposed to do, they were making the most of it, they beat all the odds — and that’s probably why they were targeted.

And I think a story like hers, including the bravery of her testimony and coming forward and saying, “We lost everything. Abe was part of our everything. But we lost our home, we lost our property, we lost our cash, we lost the means to support ourselves, we lost everything. They left us with nothing.” I think a story like hers cuts through the story that the nation has told itself, the story the nation has told about Reconstruction just failing without clarifying who failed to do what. And that failure narrative also plays into the Lost Cause theory, which is that Black people fail to make the most of freedom. So, when we’re not clear on who failed to do what, then people are often filling in those gaps with those racist assumptions about Black people not doing what they’re supposed to do. When you look at their testimonies — when you understand that they are going there, they’re reporting to federal officials with the hope that they’ll get justice, with the hope that federal officials will intervene in the violence so that they can be safe, and so they can fulfill their visions for their family’s futures. When you understand that, that’s what they want, and that’s what they don’t get, it cuts through a lot of the stories of American exceptionalism and of unending progress.

Rucker: Wow, you are really like slashing through some of the core myths and symbols of what it means to be in the United States. Something you’re saying that I want to make sure I stamp it so if I were still in the classroom teaching my introduction to African American History and Culture course, I want to make sure I heard you correctly. So, Eliza Lyons and her family see freedom, they make the transition from shadow slavery, from being owned as property to owning property. Their children are enrolled in school, they’re making the most of their freedom as espoused by the United States — these particular ways that we define freedom. But then they are confronted with freedom-denying white vigilantes and an apathetic U.S. government. Essentially, the story we are told is, they needed to pull up their trousers — we might say jeans or pants today — but really they did everything we were supposed to do, so to speak. But it sounds like you’re saying that’s exactly why they were targeted. And the reason why we know that is because then they were courageous enough, when they didn’t know if any help was going to come beyond the help that they were provided within the community. If they would get any kind of recourse. Is that what you’re saying?

Williams: That’s exactly what I’m saying, and that’s what the records reveal. They’ve been sitting there all along.

Rucker: Wow. Let’s dive into this a little bit, because I want to ask about testimony. But, if you don’t mind inserting your point of view as a historian, why do you think the records that have existed haven’t been interpreted in the way that you’re offering us? I mean, I have some ideas, but I’m just curious.

Williams: I think there are a couple of things. One, I think that first pass never gets it right. I think what a lot of people were doing was authenticating, verifying, the fact of election violence. They’re like, “We understand there was some violence,” so they’re going into the records and they’re like, “Yes, there’s a lot of violence, there’s election violence.” That became the story that they were willing to tell. I also think that — and you’re at the University of Maryland, Elsa Barkley Brown. When I was a graduate student, I was trying to look for models to do the kind of history that you see in the book and I was coming up short. Elsa laughed and she said, “That’s because you’re looking at U.S. historians are doing.” She says, “They don’t know how to study this violence. You need to look elsewhere.” She said, “You need to look at conflict violence and what will become postcolonial studies (what will later become critical trauma studies). They have an understanding of what violence does to people, and you need to look to them for models.” And so I did.

So, when I was able to look to those models, look to that scholarship, I came back to the archives, or to the sources, in a very different way — with a new lens. And I was able to see things that I hadn’t been able to see, and see things that I think other historians hadn’t been able to see either. And that’s what you see reflected in the book. I also think that for some historians there is the refusal to believe Black people, the refusal to recognize when they say they’ve been harmed. There are some historians who are more interested in Black armed self resistance, and they don’t want to see or acknowledge people being hurt by the realities of racist violence. They don’t want to see a story like AIDS, which I didn’t discuss before, but he experienced paralytic fright, not because he was a coward, but because he probably had a prior trauma in his life. And so he completely froze. What we assume are the automatic flight and fight responses, he did not have those options with his brain shut down, and Eliza’s testimony about what happened to him reveals that. So I think historians have missed some of those details. I also think historians are really uncomfortable with trauma, generally, and really uncomfortable with Black trauma from white violence. So there’s a discomfort, there’s a refusal, there’s a resistance, there’s a denial going on there, that we as a field, I think, have to come to terms with.

Rucker: I agree, and in my experience in K–12, there was a lot that we needed to come to terms with in terms of the intersections of trauma and instruction in culturally sustaining pedagogy. I wanted to stay here with the archive, because as I was transitioning out of the classroom as a teacher, and now as a student, there was this movement across my friends, where folks were like, “Yeah, I’m being asked to teach from this cookie cutter curriculum.” So it’s almost like the archive in a sense, like these are the documents, these are the curriculum, the materials we’re being asked to use. But what I’m hearing you say is even there you heard the voices that were speaking to you. Even as classroom teachers, we have that agency and autonomy. Some of us more than others, I should say.

But I want to stick with testimony. You say some very powerful things through the sources that you interpret about Black people using testimonies, serving as witnesses of freedom constructing and survival strategies throughout the history of the United States. So, I’ve come to understand that this is really true in the era of Reconstruction. Dive a little bit deeper into how you see the dynamic of testimony and witness in Black people’s experiences of terror through the era of Reconstruction. For example, how might an educator or librarian help students use testimonials to really, fully flesh out this experience of Reconstruction?

Williams: I think they might do it by understanding that bearing witness to the violence was critical to African Americans’ sense of dignity and self-regard. The injustice of these attacks on people who had done nothing but what they were supposed to do, what they have been instructed to do, what they wanted to do. This injustice of being attacked empowered a lot of people to step forward at great risk to themselves, and they needed to say the names of their slain kin, to identify their attackers, to challenge efforts to trivialize what happened to them, and hopefully to inspire federal officials and their fellow citizens to help end the violence. Their actions do work to a degree — some of the violence is tamped down on, but not nearly enough. And it’s not because Black people didn’t want it to, but because there wasn’t a collective will in order to end this violence.

But, I think in the process what African Americans do is they create their own register of Reconstruction. It’s a counter narrative that has stood on the record books for 150 years that revealed the true story about what happened. So it’s been there. I think one of the most powerful acts or examples of testimony is the fact that they all come together from different communities to do this work because that’s how important they recognize it is for them to produce records, for them to document, for them to account, for them to report what was happening to them. I think in many ways it serves as a kind of moral ledger about the nation, about Reconstruction. I think educators going into the records and examining them can really take a look at them and try to get a sense, and help students get a sense, of what has happened to African Americans, what do they seem to want by testifying, and how does the nation respond and why? What does this tell us about the nation and what does this tell us about African Americans?

Rucker: This is powerful. As you’re sharing, I’m thinking about how often I might minimize or trivialize my own personal records, and how important it is to have my cell phone out and available. How important photographs like family photo albums are, because that is my opportunity to be a witness to my own freedom and to our communities’ collective fight for freedom. So yes, yes, yes.

Williams: I’ll just add, collecting those stories of the elders — your parents and leaving your own records — I think that’s part of the work that everyone needs to be doing.

Rucker: Thank you. And I hope my mom is on here, I’ve been trying to get her to record our oral history. I want to talk about language. And then after the break, I do want to come back because I’ve been kind of dancing around this notion of violence and trauma. After the break I want to get from you some practical strategies for how to talk through, how to teach us the realities of the war on Black freedom.

As I was reading the book I noticed that you very deliberately use words and phrases to frame Black people’s experiences during Reconstruction in the south. For example, in chapter two, The Devil Was Turned Loose — first, I just liked that the titles are also quotes from the testimonies that you gathered; I think that was a very important way to center the voices of those bearing witness — but you write, “the real business of waging war on Black people’s freedom didn’t happen on the battlefield, in the White House, or in the chambers of Congress. Rather than only attacking army posts, or fighting the politicians who made freedom and civil and political rights for Black people possible, extremest whites were calculating the work of overthrowing Black Reconstruction happen on the ground in the former slaveholding states as white conservatives got busy establishing institutions and policies that would sustain Black people’s subjugation.” You use so many different words.

So let me get to the question. Teachers are often cautioned to keep our points of view out of the curriculum, but your language is so passionate it takes sides. It doesn’t pretend, it doesn’t purport to neutrality. So your book, for me, was an invitation and a rallying cry not to be afraid to name exactly who did what and to whom, because of what those actions mean in real people’s lives. So, tell us about how and why you selected the language that you did throughout the book — even things like “survivor” or “extremist” or “terrorist,” “combatants,” “assailants,” the “shadow army” — tell us about those words.

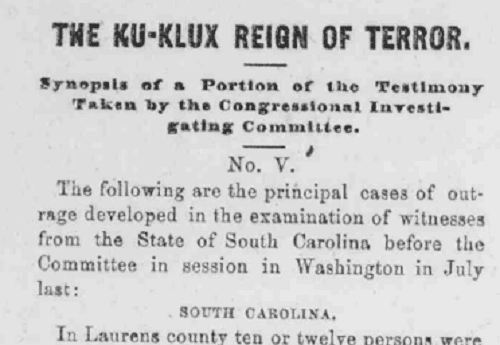

Williams: I wanted to be really precise because I think that imprecision is an act of erasure, and it makes it hard to see and understand who is doing what to whom and why. So, I think the more precise language the better. I also recognize the ways that the there are terms, etc., that we recognize fully today, but a lot of Americans would associate them with somewhere else. The notions of American exceptionalism, they’ll say, extremists and terrorism is something that happens elsewhere. Or, it happens to Americans; Americans don’t do this. But the archive, the Black archives in particular, and even the larger white archives, revealed what actually happened. They revealed that there is extremist violence, members of Congress use the language of terror to describe what happened during Reconstruction. There’s this language of “the reign of terror” in the language of the Klan hearings, in one of the reports. There’s this tendency of Americans to associate this kind of violence with other places and not recognize it here, and Black people know that that’s simply not true. The record reveals that that’s not true. So I wanted to use precise language because I think that’s reflected in the archive, and I also wanted to draw associations that I thought would be familiar with Americans, even if it makes them uncomfortable.

Now, for the thing about teachers, I think we need to stop pretending that teachers haven’t been taking sides in what they teach, in how they teach — including the language they use, and what they do with it — especially when it comes to Black and brown people’s histories. There is this assumption that teachers haven’t been taking sides, and they have been. I think about Donald Yacovone’s work Teaching White Supremacy. It’s more than 100 years of teachers, in particular, making very specific decisions to take sides. But the sides they were taking were with white supremacy, and that became normalized and okay. It was something that people just don’t talk about. So now, in this moment, when you’ve got a movement, you’ve got the results of movements for justice that want to get us to a better place and want to do that by teaching an accurate history, now we’ve got the language like “this language is politicized,” [and] “you’re taking sides.”

As a historian, I recognize the privileges of being a professor in the state of Michigan with tenure, but I’m on the side of justice. If some teachers aren’t on the side of justice, and they’re not going to teach their students to be on the side of justice, then we’re just not on the same team. I feel like we need to be honest about that. But more specifically, we need to be honest about and push back against this notion that teachers have not been taking sides. As a Black girl who came up through the K through 12 system — and through college and even as a professor today — I have never experienced a time where I have not known teachers or professors to be taking sides. It’s just that their sides are not necessarily like . . . it may or may not be a full on declaration of association with a political party, but teachers are taking sides. They are making choices in the language they use, in the histories they teach, et cetera.

But what has become politicized, I think today, is teaching that engages justice issues. We need to be aware of that and then figure out how to go forward from that.

Rucker: This is a rallying cry, because just like the freedom singers saying “what side are you on?” We’re about to go into breakout rooms.

All right, welcome back, everybody. I hope you had a rich discussion. We would love to hear what you discussed in your breakout session, so please continue to share in the chat and shout out your group. And please do drop questions too. But before we return to the conversation, I want to remind you that we have more wonderful sessions coming up and related lessons. So, please do join us next month for the session on Monday, April 24, with Linda Villarosa on Under the Skin: The Hidden Toll of Racism on American Lives and on the Health of Our Nation. Even if you are not a teacher there are ways to get involved. Please, y’all we need everybody. All of us are warriors who are committed to this war for freedom, get involved in your local school board, attend meetings, testify, vote if you have that enfranchisement right, run for office, join us on June 10, donate to the Zinn Education Project so that we can continue to offer these classes and offer lessons to teachers for free and defend their right to use them. So please offer your time, your talent and your treasures.

We are going to have time. I’m going to transition. That wasn’t so graceful. We are going to have time for just a few more questions, but before we do, as I stated before the break, I want to specifically talk about violence. I want to really zero in right now on our pre K through 12 educators, all educators but primarily my pre K through 12 comrades — you have been asked to grapple with how to teach the history of the United States without overwhelming our students with the horrors of genocidal and racialized terror. Many educators are also grappling with threats and policies to restrict them from teaching young people the truth. These tactics have been a throughline from Reconstruction, when white supremacists threatened teachers at Freedom Schools and literally burned down school houses to suppress equitable education and progress. So, I’m saying this in this spirit now. Dr. Williams, could you tell us more about the violence, specifically against educators during Reconstruction, and then draw a connection for us to the attacks on teachers in Black history today?

Williams: I think it’s important to recognize that attacks on education and on educators are part of a larger freedom-denying enterprise, and I think that’s where you see the similarities between what happened during Reconstruction, what happened during Jim Crow, and what’s happening in this moment right now. I think part of it is because you see people who don’t believe in liberty, freedom, and justice for everyone. I recognize that young people know the difference between right and wrong, and so if teachers share with them some of the stories of injustice, of enslavement, of denials of freedom, of rights, of bodily integrity, etc., they know that young people are going to say, “Well, that’s wrong, we shouldn’t do that anymore. We should build a better world.” And they want to make sure that that doesn’t happen. That’s why you see these attacks. That’s why you see what’s happening right now.

You see an escalation of it, especially post 2020, when you’ve got more and more people, including more and more teachers — and not just teachers, but white teachers in particular — who understand and who understand this moment, who either know the history or who’ve been digging into the history. And they want to teach the history that’s accurate, the history that helps their students understand the world that we live in right now, and to help them build a better world. The way to address that, the way to nip that in the bud, is to deliberately target teachers — if not with physical violence, although sometimes with physical violence, then denials of their right to teach accurate history in the classroom.

I think it’s curious that they are strategically targeted. You know, no one’s saying you can’t teach Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind as the gospel, although we know teachers are doing that. No one’s saying you can’t teach Dunning or D. W. Griffith as gospel, although we know teachers are doing that. So, we need to be aware of that. The one thing that I think that teachers need to think about — but also parents who may be in the room, and students who may be in the room need to think about is one teachers — they don’t have to rush to comply, or over comply, I think they just need to sit with and think about and be more strategic about the history that they’re teaching. A lot of times, they’re getting that pressure to focus on scholarly interpretation when the primary sources will essentially do the same kind of aid. A lot of people who are passing these laws don’t know enough about the primary sources to stop people from doing it. So I think that that’s one thing to think about.

I think the other thing to think about is for parents and communities to remember that Black education has never only happened in the classroom. The Black Freedom Movement, the Black education movement, wasn’t stopped by bans prohibiting people from teaching enslaved people how to read and write. The Black education movement wasn’t stopped by Jim Crow. Black parents, Black communities, Black teachers, and even some white teachers came together to make sure that the kids had the education they needed. That learning doesn’t only have to take place in school. Now, this isn’t to say we turn our backs on schools, because I don’t believe that. I think it’s a both/and, a recognition that education and history can take place in a number of spaces, and the history of Black people illuminates that. Black education happened in homes, in families, in schools and churches and on the porch, in the community room, on the playground. It happened in all of these places and we need to support the history education movement happening today, to work our way through — especially for those teachers who are under the threat of these laws and these bans that we’re seeing.

I think we just need a little more strategy. And I think we need to come together and to support each other, because they can’t fire us all. I mean, they may try, but it’ll be hard for them to work through that without undercutting the education of the nation. And they might actually do that. That’s why, as Jessica said, we have to rally, we have to do all of these things. We have to be at school board meetings, we have to be at those meetings where they’re discussing the history curriculum for the state. That’s not just at the school board, that’s at the state level, where they’re talking about the history curriculum. We need to be in all of those spaces advocating for accurate, rigorously researched history.

Rucker: Powerful stuff. What I’m hearing is some ujima, some collective work and responsibility. In fact, one of my favorite teachers is on here, who’s not a classroom teacher, but is a teacher because the world is her classroom. What I wanted to say to people who educate outside of the formal classroom space, we’ve also got to rally around those folks who don’t keep their lights on by pledging to teach the truth. We might need to come up with a meal or something, because going back to the work, we’re talking about the trauma that was literally visited upon our cultural ancestors, and then now the trauma of wanting to teach that history accurately and honestly while we are also having those same forces of trauma reenacted on us for wanting to teach the truth. So, I love this idea that our movement needs to be just as nimble, if not more than, the strategies that have been used to wage war against Black freedom.

But the thing that I really want to underscore here is that it is our responsibility, collectively, to talk about violence, because one of the most dangerous things I could have done — and I used to, I’m grateful that books like this intervene — was to teach students about Black resistance but to never give them appropriate context of what Black people were resisting. That means that I have to talk openly and honestly, very delicately and tenderly and age appropriately. But I owe that to both the benevolent ancestors and to us, as the offspring.

So, I want to ask a second question, still connected to this notion of violence. So again, violence is central to Reconstruction’s undoing, because, spoiler alert, we actually won. That’s one of the myths that you laid out earlier. So violence is central to Reconstruction’s undoing and a critical part of this history. How do you suggest educators think about or approach the question of violence when they’re building lessons and units for their students, and when delivering said lessons?

Williams: That’s a great question. I think one of the things that we have to recognize is that violence comes in a variety of forms. There’s physical violence, there’s psychological violence, there’s economic violence. As you teach about the violence, you can be strategic in what you do to try to be diverse about it. So, there’s the physical and psychological violence of enslavement, if you’re wondering, and of klan attacks; but there’s economic violence, too. Denying people the means, denying people enough to live on, denying people labor autonomy to work where they want to work, denying people a living wage — that is economic violence. We need to acknowledge that.

But I also think that as we think about the violence, we need to do more than just teach that violence is occurring, we need to help students understand what the violence is used to achieve. Klan violence, lynching, etc. is used in a very specific way in order to discourage Black people from seizing or continuing to seize their freedom. Economic violence is part of a larger extractive process, another way to steal Black people’s labor and livelihood. And theft, as we know, is violent. There is this tendency to shy away from it. I also think that when we’re teaching about violence against Black people we need to acknowledge things like slavery as state violence. Aggressive policing, Jim Crow policing that is violent. There’s a tendency to read that treatment, read the sort of the violence of racist subjugation, as something other than violent. So we need to acknowledge the complexity of the violence.

We need to acknowledge the realities of Black people resisting, so I’m not one who shies away from the resistance. But I want to make sure we make sure that we’re communicating what Black people are resisting. They are resisting having their lives taken, they are resisting having their livelihood stolen, they are resisting having their children’s futures obstructed or undermined by this violence. So we need to have a very clear understanding of that.

I am anti bringing lynching photos into the classroom for a variety of reasons. I think it’s unethical unless you can tell that person’s full story from top to bottom. But there are plenty of other sources to use and tell. There are testimonies, there are affidavits, there are all of these records. There are short stories, there’s poetry, there’s Black folklore. All of these illuminate the complexities of the violence, and they represent the kinds of sources that teachers can use to create age appropriate lesson plans to help students see the violence and what the violence is used to achieve. And, to the best of their ability, what Black people think and feel and know about the violence I think also matters.

Rucker: Dr. Williams, I just thank you so much, because it all matters and what you’re saying about the sources we use, how we interpret them, this notion of the Black archive that you talked about. The Black archive is both a physical space but also as a method, just like Black Twitter and Black Lives matter. I love what you said about really asking students to grapple with what was the function of this violence. Like, let’s look at the fact that sexual assault of Black women, of Black children, you showed me in very pornographic ways, was a big part of this. And yeah, Black children were not immune.

Anyways, there are some questions, so I want to give space to my curriculum comrades here in the chat. Before I transition, anything else on the topic? Okay, great. From Terence, “Maybe you can mention teaching and learning histories as connected to a world history in geography for accurate worldview and understanding.” I love this notion, Reconstruction in a transnational context, or just what you were saying even about having Black labor exploited, that’s violence. Racial capitalism, that’s violence.

Williams: So, I don’t have anything to add to that. I think that you can do it in a global context. I’m not opposed to global context. But I also think that sometimes you have to strike the right balance between it, because the global context, sort of zooming out, makes it harder for you to see some of the very specific things that matter. So, I think what teachers might benefit from doing is figuring out how to zoom in and zoom out, and in different contexts, to help students see this from different angles. So it’s not the same thing as a puzzle piece, but it’s being able to see the whole world, about what’s happening, but trying to figure out a way to not zoom out as a way to deflect and avoid dealing with the reality of what’s happening on the ground.

Rucker: That’s right, sometimes we’ve got to sit in that fire. But it’s so uncomfortable. The uncomfortable thing about discomfort, that’s where we actually grow, right? We grow in the truth of our discomfort as a nation.

All right, another question from the chat. Kumar said, “In this climate of woke war [that’s new to me], where folks are weaponizing words, theories, and histories they don’t understand, how do we respond to people in unchecked positions of privilege and power? For example, board members who claim that this history, like the 1619 Project, is not accurate, or that we have other high priority items to address in schools instead of hard history.”

Williams: I think part of it . . . I love Tony Morrison’s statement that racism keeps you distracted. I think part of it is, for me, my thing is to not be given the runaround, or play for the okey doke. I know exactly the games and all the rest of the stuff and so I’m not going to be distracted by that. Because that’s part of what they want, they want you distracted. They want you running around trying to define what woke means, as opposed to fighting the injustice in terms of the law, in terms of showing up at the school board. The people who want to talk about accurate history, they never do well with professional historians. I asked for receipts on history education, I asked about their qualifications to assess any kind of history. Then what you realize when you do that, people, they get in their feelings and they get defensive. That’s me, I want them defensive because I know what they’re doing. Part of what we have to do in waging this fight is to not get distracted, to realize sometimes we’re just being trolled. And also to challenge . . . you know, I think the fight over wokeness, it’s to not argue with the people who are distorting it, but to argue and to challenge the people who are enabling it. Like the media, that is playing along in the discourse. They are the ones who are playing the okey doke, and they’re the ones who are often getting played. We need to highlight their role in this, their complicity, and then to act accordingly. Sometimes that may mean canceling the newspaper or turning off the TV. Being more strategic. For me, I’m not getting distracted by white supremacist games because I know those games, I know how they’re played. So while other people are running around chasing the ball, I’m still on the frontlines. So, I invite other people to stick with me on the frontlines and do what we need to do in this justice fight, and not chase the racist ball that they’re kicking down the street.

Rucker: Dr. Williams, I’m trying to sit next to you at the cookout! I’m not getting distracted by these white supremacist games. I’m with you. We have another question in the chat from Howard, “Can you talk about why white students need this history?”

Williams: I think white students need this history because they’ve been sold a bill of goods. They’ve been lied to, too. They don’t understand the world that we live in.

Rucker: They’ve been bamboozled.

Williams: Right. So, they don’t understand the world that we live in, but many of them want to. I teach a lot of white students [and] the vast majority of students in my African American history class for the past couple of years have been white students who are curious, who want to understand the world we live in. What they come out of the course thinking and understanding and knowing is that they feel bamboozled. They feel bamboozled by their K through 12 teachers. So there’s this question of why don’t we know, why haven’t we been taught this? Why do we have to go to college in order to learn this? What about my cousin who can’t go to college, is he never going to learn this? They are asking these questions because they also want a better world.

I think a lot of white students also recognize the point that Lani Guinier made in terms of Black people being the canary in the coal mine. What has come for Black people is going to come for everyone. The toleration of the injustice and the inequality, the growing inequality, the wealth gap, all of those things will come for the larger white population, too. I also think that white students want to know this history because they believe in justice and they want a just world, too. This isn’t just the history that Black people want to know or need to know. But I also think we need to have a conversation about some Black students thinking that because they’re Black they automatically know the history. That’s a different conversation. But I think everyone benefits from this history because they understand the world we live in now.

What I can tell you is that when students come through either the the second part of the survey, they understand the world we live in right now better. The world makes sense. They can understand how we got from Reconstruction to George Floyd. Before there was a big gap coming through and having an accurate history, they [now] understand what has happened and they understand what we need to do now in this moment to stop this from happening again in the future.

Rucker: Yes, indeed, thank you. Thank you. Okay, so this is coming from Dominique, “As states are passing restrictive laws for education, what can we push Congress to pass nationwide?”

Williams: Because so much K through 12 education is at the state level, I think a lot of the work is going to be coming primarily through the states. So I think part of what needs to happen is that teachers and parents need to vote accordingly, especially at the state level. A lot of these laws are implemented at the state level because education is so grounded in what’s happened at the state level. So this is a state level fight. I think one of the biggest lies that the Democratic Party has sold over the years is that federal elections are the only elections that matter. That has never been the case and that is not now the case. Federal policy isn’t going to stop these laws from being passed. What will stop them more than likely are people voting accordingly, voting out people in office who support these laws, voting out elected members of the school board, running for school board, making sure you’re showing up at those meetings and that you’re calling people in and out. You also have to hold lawmakers accountable. If they don’t vote against the law then you need to send them packing, they should pack their bags and go. So again, I don’t think that this is something that can be handled at the federal level. This is a state issue and a local issue, primarily.

Rucker: That’s right. So unless I am missing any questions, I think, if not, I want us to wrap up. I want to read something please. Friends bear with me, but this really struck me.

But what targeted people in the warmth of freedom, like Andrew and Frankie Cathcart, Mary and Joseph Brown, and what Eliza Lyons knew and tried to communicate to anyone who would listen was that families were the cornerstones of their individual and collective freedom. Family was the glue that bound people together. Voting, office holding, and equal rights were means to a future in which Black families would be free and secure. That was why Confederates struck at the very heart of freedom when they overthrew the revolutionary experiment in multiracial democracy. Understanding Black family stories of racing into freedom and the price white right-wingers made them pay in the war against it, Americans learned that the arc of our history doesn’t always bend towards justice. The real story is essential to understanding why, more than a century and a half later, our struggling continues.

So our struggle continues, warriors, and I consider you all my thought family. My hope is that these stories don’t just stay here, but that we share them. And again, please love up on your K–12 educators because we all need each other.

So, with that said, I want to say thank you, thank you, thank you, Dr. Williams. Because I know right now, my grandma is staring at me and saying “Dr. Williams understood the assignment.” And I’m like, “Yo, you put your whole foot in this book.” So thank you so much.

Williams: Thank you so much for having me. Thank you so much for the wonderful questions. It’s been such a pleasure being in conversation with you, Jessica, and with the audience.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

Many of the lessons, books, reports, and podcasts recommended by the presenters and participants.

Lessons

|

|

Reconstructing the South: A Role Play by Bill Bigelow Reconstructing the South: What Really Happened by Mimi Eisen and Ursula Wolfe-Rocca Teaching With Seizing Freedom by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca When the Impossible Suddenly Became Possible: A Reconstruction Mixer by Adam Sanchez and Nqobile Mthethwa Who Killed Reconstruction? A Trial Role Play by Adam Sanchez Find more recommended lessons at our Teach Reconstruction campaign page. |

Books

|

In addition to Williams’ I Saw Death Coming: A History of Terror and Survival in the War Against Reconstruction, the following books were referenced. They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonies of Racial Violence from Emancipation to World War I by Kidada Williams (New York University Press) Black Reconstruction in America by W. E. B. Du Bois (Penguin Random House) Black Was the Ink by Michelle Coles (Lee & Low Books) Find more recommended books for K–12 and adults on Reconstruction at Social Justice Books. |

Reports

|

Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction (Zinn Education Project) Reconstruction in America: Racial Violence after the Civil War, 1865-1876 (Equal Justice Initiative) |

Podcasts

|

Seizing Freedom by Kidada E. Williams offers stories about how African Americans freed themselves during the Civil War and built new lives during Reconstruction. Teaching Hard History: Reconstruction 101: Progress and Backlash with Hasan Jeffries via Learning for Justice, interviewing Kate Masur and Ahmad Ward. Slate on Reconstruction with Jamelle Bouie and Rebecca Onion. Seven episodes (and a political overview) on civil rights, land ownership, self-defense, and more. Find more recommended podcasts at our Reconstruction report’s resources page. |

This Day In History

The dates below come from our This Day in History collection, which contains hundreds of entries all searchable by date, state, theme, and keyword(s).

Participant Reflections

With more than 240 attendees, polls showed attendees were 48% K–12 teachers, 11% teacher educators, 8% historians, and 8% family members of a student. Below are more comments that participants shared in their end-of-session evaluations.

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

The most important thing that I learned today is that there is an abundance of primary sources that tell the narrative of Reconstruction that have been hidden from us, and that if we read the testimony at Klan trials, documented narratives, etc., we will see the truth revealed.

Teachers need to evaluate the type of history they are teaching. Whose history? Bring in primary sources to tell the story of Reconstruction.

Choose your side, stick to your position, be assertive and don’t let the supremacist games get to you. Understand the levels and the complexities of violence. Reconstruction is not over; it is still happening. Who gets to talk about trauma, and how does trauma get talked about? Who failed, or is failing, Reconstruction? Educators need to move away from sanitized history. And finally, new technologies can make learning and teaching accurate histories — especially hard histories — more possible due to the new accessibilities that have come along with new technologies.

The importance of reading primary sources from the lens of trauma and how that informs the narrative of Black families and the erasure they have experienced.

Teachers take sides in the language they use.

The importance of precision with my words and language. When the correct language is not used it is an act of erasure.

Reconstruction didn’t fail: Who failed to do what? Stop pretending that teachers are not taking sides. What is violence used to achieve?

The most important thing I learned was how critical it is to understand that violence comes in many forms — physical, emotional, economic. And not just understanding and teaching about that violence but getting students to recognize the goals of said violence.

How the narratives can help students understand more deeply the experience of Reconstruction. Teaching it can help counter the racist idea that Black people didn’t do enough.

It’s important to record your history as you are living it. There are stories to be told. While it may seem insignificant to us now, it is our first hand account and the legacy that we leave.

What will you do with what you learned?

Use the primary sources strategically, especially those that document and center Black voices, because they tell us a lot about what was going on during Reconstruction.

I am absolutely stealing questions that Jessica brought up about the role of Black people to bear witness to the truths of what happened to them: :”What do they want by testifying? How does the nation respond and why? What does this tell us about the nation and what does this tell us about African Americans?”

I plan to utilize all of this richness in my own community in Texas and continue to have these conversations with my own children and grandchildren so that they can be best educated outside of the classroom and know what is off with the educational system.

I will use some of the reframing questions of “Who failed to do what?” and “What was the violence aiming to achieve?” in discussions around Reconstruction.

I connected with an educator and plan to volunteer and participate at the school board level.

I will be including Dr. Williams’ wonderful new book in a book event I’m running next month with undergraduate students, and this event helped to open my understanding of the book and the invaluable research — all of which I will also personally be incorporating in my future endeavors as an educator.

Absolutely share this knowledge with others and continue broadening the scope of hard history with my children.

I support educators at the district level in a capacity not directly related to curriculum and instruction. However, I collaborate with many who do. As a white educator, I am trying to build on my own knowledge base so I become grounded and can speak confidently about the true history about Reconstruction and advocate for it to be a part of our learning community at all levels.

I am a librarian and I will use this information every chance I get when I approach someone who supports the idea of removing Black history, is not woke, or is acting out as white fragility, etc.

Centering Reconstruction around the story of those making the most of freedom and how it could be taken away in an instant.

I’m a teacher of teachers in museum education. This experience helps solidify my work in encouraging museum teachers to develop programming that expands the opportunities for all visitors and participants to learn and engage with the truth of U.S. history.

I will share these resources with teachers and add to class curricula.

Continue to add the personal narratives to my high school curriculum, and keep reminding my students to ask for the stories they feel they aren’t hearing enough of, to hear the voices they know should be represented.

Presenters

Kidada E. Williams is the author of I Saw Death Coming: A History of Terror and Survival in the War Against Reconstruction and They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonies of Racial Violence from Emancipation to World War I. She teaches courses on African American and U.S. history and historical research methods at Wayne State University. Williams is also one of the co-developers of #CharlestonSyllabus, a crowd-sourced project that helped people understand the historical context surrounding the 2015 racial massacre at Charleston’s Emanuel AME Church.

Jessica Rucker is a graduate student in the Department of American Studies at the University of Maryland, College Park, and a Prentiss Charney Fellow. Prior to her graduate work, she was a high school teacher in Washington, D.C.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn