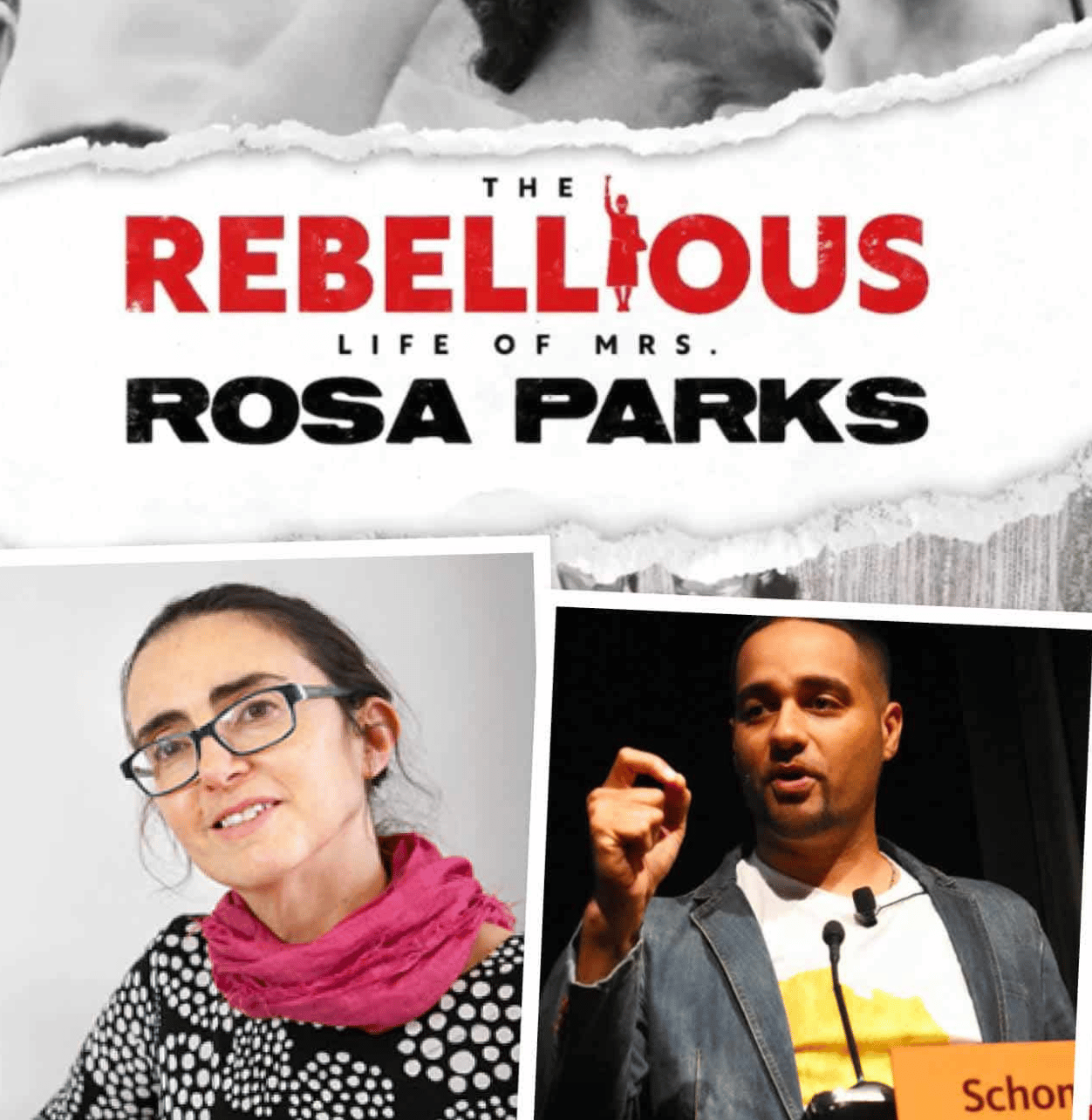

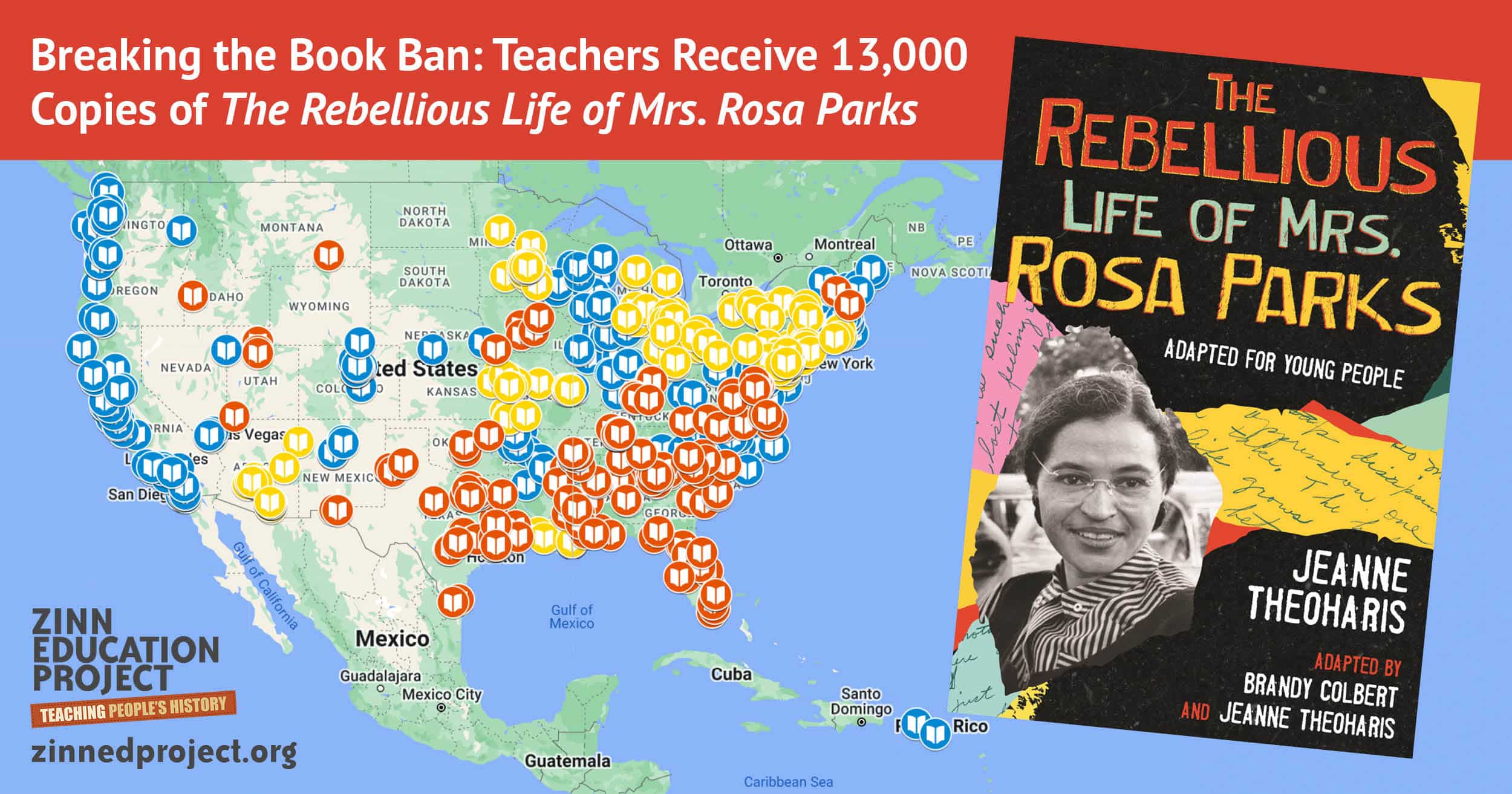

On February 6, 2023, historian Jeanne Theoharis joined Jesse Hagopian to share and discuss clips from the new documentary The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, based on the book of the same name by Theoharis.

The documentary is available to view on Peacock, and teachers and teacher educators can request a free license to stream the film for their classes through March 31, 2023.

The documentary is available to view on Peacock, and teachers and teacher educators can request a free license to stream the film for their classes through March 31, 2023.

This session — held on the first day of Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action 2023 and co-sponsored by AFT Share My Lesson — was part of our monthly Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online class series. Don’t miss the 2023 lineup — register now.

Participants shared what they learned and additional reflections on the session:

There are many sides to Rosa Parks — more than just refusing to give up her seat on the bus!

Rosa Parks was much more radical than people teach.

I think one of the most important things I learned was how long she was in this work and how as a woman she faced even more challenges, but that she kept going. I also learned how much Rosa liked young people and wanted them to lead, as well. Having her support as a young educator is inspiring.

Rosa Parks and other women like her were powerhouses. Her story is so much bigger than the moment that is shared in most books we share with students. If we want to raise students who will change the world, we need to see the ground swell and the hardships and the risks.

Dr. Theoharis’ reminder that Rosa Parks is an avenue to teach many elements of the freedom struggle. In particular, the idea that teaching about the Detroit uprising can be a way to lead into teaching about movements in our city and modern activists.

Freedom is a slow, long, agonizing group effort!

I learned about some fantastic resources that I will share with staff and was reminded about the important roles that Rosa Parks played in the Civil Rights Movement. I was not aware of the economic sacrifice that Rosa Parks made and can only imagine the toll that took on her life. My two takeaway questions are: 1. How did patriarchy impact the outcomes of the Civil Rights Movement? 2. How does misogyny impact social movements?

I’m very excited to watch the video and show it to my 100 11th graders so they can learn more about Rosa Parks. While the standards for my course do not explicitly cover Mrs. Parks, her story is one that needs to be heard!

The Rosa Parks story was greatly whitewashed for the capitalist narrative even more than I even thought. I consider myself highly educated on the subject, and I still learned multiple things that haven’t even come up in my classes on activism.

I learned about the importance of a whole life perspective instead of standalone clips or misleading characterizations, as has been done with Rosa Parks.

The importance of teaching about the person and the multiple roles in which activists such as Rosa Parks contributed to the Civil Rights Movement. A person’s contributions should not be defined by one event and/or action in time. There is more to a person behind the story, which history tends to distort.

The idea that the swift flattening of Rosa Park’s story and the whole bus boycott is the type of oversimplification that is happening with historical events now, and it’s up to us to recognize and push back against this type of erasure.

Thank you for bringing together educators and students in such a meaningful format!

Event Recording

Recording of the full session, except for the breakout rooms and clips shown from the documentary.

Video Clips Shown During Session

If you screen the documentary The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks in your classroom or learning space and want to include the clips shown during this session, here are the timestamps for navigating to those specific spots.

- Intro on master narratives of Mrs. Parks — 0:00–4:00

- Activism around sexual violence (Recy Taylor and Joan Little) — 24:15–31:07

- Bus Boycott (the bus boycott organizing begins, to Kings speech at Holt) — 46:28–48:57

- Rosa Parks’ suffering and the difficulties that ensue for her family — 56:30–1:02:17

- March on Washington (and sexism of the movement) — 1:04:23–1:07:07

- Detroit Uprising and People’s Tribunal — 1:09:20–1:12:58

- Conclusion (and understanding this history for today) — 1:31:51–1:35:52

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: Well, welcome everybody. Thank you for being here. I want to begin by just saying happy Black History Month, and happy Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action. What a great day to be having this session, and what a great day for you all to choose to be with us. On behalf of the Zinn Education Project, we would like to welcome everybody to our class with Jeanne Theoharis on the documentary film about Rosa Parks.

Some of you have joined us today for the first time. If so, special welcome to you, and we hope you come back. But many of you have also participated since we launched this series. It’s really a gift to be able to share this time and build this virtual community with so many incredible educators, organizers, community members, students, and parents. Today’s class is hosted by the Zinn Education Project, which is coordinated by Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change as part of our Teaching for Black Lives Campaign. We have members with us this evening who are here from the Teaching for Black Lives study group. So, if you’re in one of those study groups, please put T4BL after your name, we’d appreciate that.

I wanted to make sure everybody knows that the Zinn Education Project offers free downloadable people’s history lessons. Many of you have used these lessons for middle and high school classrooms. You can just go to the Zinn Education Project website to get these lessons, including some lessons directly relevant to tonight’s session, such as a teaching guide on The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, [and] both the film and the book. I was honored to join Jeanne and an incredible group of educators to help create some of the lessons there and I can highly recommend them. We’ll talk more about the lessons throughout this evening’s program.

I want to be sure to emphasize that tonight’s session is being held during Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action, in support of this week of action. It’s also co-sponsored by AFT Share My Lesson. We’re really happy that the American Federation of Teachers is supporting this event. The AFT will hold a screening of the full documentary and is offering books and a sweepstakes. We’ll share the links to that in our follow up email to you all. I also want to give special thanks to the ASL interpreters who are with us this evening — our interpreters are Krystal Butler and Kaylee Teixeira. Thank you for being with us and making this event accessible.

Before we begin our conversation, we wanted to find out who is in the room, and go through our plans for our time together. So, we are going to put a poll up now so we can find out how many teachers are in the house, how many educators, librarians, teacher educators, historians, parents, students, and all the rest of you who are with us. Some of you have multiple roles, so if that’s the case, just pick your primary one. We will do a short evaluation at the end, and in about a week we will share the full recording from the session and all the resources that were shared in the chat box. We hope that as this session goes on, you all will tweet what you’re learning and let other people know they should learn about these monthly online classes, these Teach the Black Freedom Struggle classes. It looks like the results of the poll have come in: We have 50% K–12 teachers (my comrades!); we have 2% K–12 students (glad you’re with us); we have 3% family members to a student; we have 15% teacher educators; 6% historians; 2% librarians; and 22% the rest of y’all. All right, I’m glad everybody is here with us this evening.

I also want to let people know that a special feature of these Teach the Black Freedom Struggle conversations is that we will actually break in 25 minutes, and pause the dialogue, so that you all can meet each other and talk in small groups to share your thoughts with one another. I think this is really valuable time for folks to think about how they’re going to teach this in their classrooms and share ideas about what you’ve learned.

So now, I am very happy to welcome Jeanne Theoharis, the author or co-author of 11 books and numerous articles on the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements, and the contemporary politics of race in the United States, including the award winning titles, The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, and a book that I would highly recommend that you all order as well, A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History. So welcome, Jeanne. Thank you for being with us.

Jeanne Theoharis: Thanks for being here. This is so fun. I’m so excited!

Hagopian: It does blow my mind to think about when you first contacted me about the YA edition of this book. And we were like, “Oh, what an amazing idea!” And then to see this film get made on top of it

Theoharis: I know! And to get to share it with everyone tonight. And we’ve got to build all these lessons about it. It just feels like it just grows and grows and grows. When we started this series, there was no film, there was not even the possibility for the film when we started this series. Jesse and I did the first one of this series together about Rosa Parks before there was even a possibility of a documentary film.

Hagopian: That’s right. And now we have lesson plans and a documentary. I just want to say congratulations to you — you’ve put your life’s work into this, and it really shows. It’s such a magnificent film and book. I just get so excited thinking about the impact it’s going to have. So thank you.

I’ll let everyone know that throughout the session, we will be showing clips from the brand new film, and teachers can access a streaming license to show the film in their classroom. We’ll drop the form to that in the chat that you can fill out. I highly recommend everyone show this in their classroom.

We’re going to begin with the opening clip of this film. So sit back, relax, and enjoy the show.

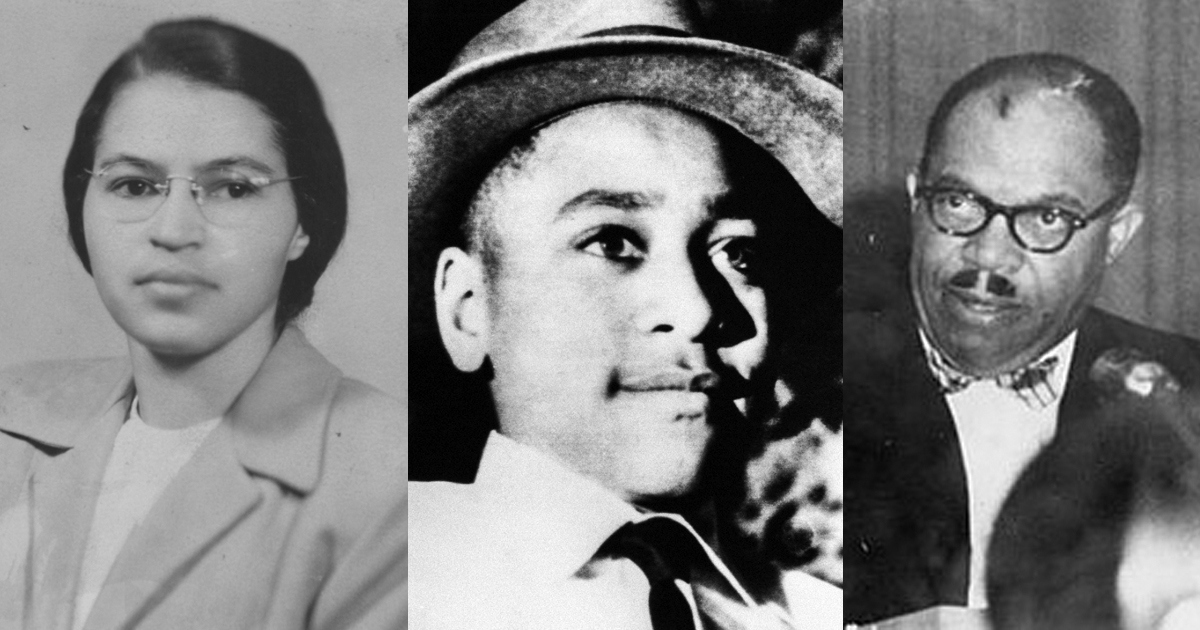

Yeah, that’s how it gets launched. I love the opening to this film. That moment where he says, “Will the real Rosa Parks please stand up?” I just feel like it’s so symbolic, really. It says a lot about what people don’t know. And so I was hoping you could talk more about that. Why is it that so few people know the real Mrs. Parks, and when they learn who the real Mrs. Parks is, how will they see her and see our nation differently?

Theoharis: I mean, I was so glad that they used it. I discovered that clip when I was working on the book and I always had this fantasy that we would use it in a film or a theater production, because it’s like watching a train wreck. It’s like Rosa Parks cosplay for one. You have all these different stereotypes of Black women. Obviously, the person who’s playing the middle class Black woman with pearls is who wins, right? Who gets the most votes. So, you have that idea of Rosa Parks wins. And for people, this game show, you won money based on being able to fool the judges. That was the whole shtick of this show. It says a lot about our idea of who she is versus who she is. There’s the real Rosa Parks — and if we got to watch the full clip of this, Nipsey Russell and her are having this whole detailed conversation and the other judges still don’t even notice, and they still vote for the middle person. Then there’s the horribleness of people being like, “Any of you could have done this,” right?

I think that gets to another myth about the way we talk about her, which is this sort of — you kind of stumble into history on one day — this sort of American myth. I think there are ways that we are often taught and learn about Rosa Parks, and we’re going to talk about this a lot tonight, that miss the kind of work, the kind of sacrifice, the kind of longevity it takes to actually change history.

On the one hand, Rosa Parks does show the power of all of us. And on the other hand, she’s tremendously extraordinary. Almost none of us could have done what she did. So, you have all of those panelists and judges being like, “Oh, yeah, any of you could have done it.” It’s such, to me, a way into really the kind of harmfulness of the ways that we’ve talked about her. I could never document this, but I think she goes on the show because she also needs money and is willing to go on the show. The show is in 1980.

I think one of the places we wanted to start tonight was, I think one of your and my favorite ways of teaching her is that it really opens up an opportunity for critical thinking. As you started off by saying, Jesse, we built a set of lessons around the film and around the Young Adult book. One of the lessons that you built was a lesson thinking about the master narratives we get about Rosa Parks. I think part of the opening kind of does it in a playful way to get us to have a conversation with students about the ways you’ve learned or the information you’ve received about Rosa Parks. And then what is it going to mean to change that?

To change that, I think students really are ready for that conversation. To change Rosa Parks means changing how we understand how social change happens; how we understand movements — not individuals; how we understand the sacrifice it takes; how we understand the whole variety of injustice that people were fighting for. I think sometimes the Civil Rights Movement gets trapped in this little box, like bus segregation. So, we’re going to get to hear her tonight, and in the full movie, and in the book, all of the different issues that they’re working on in the bus is sort of a symbolic space, because it’s a very palpable space of segregation. But she’s very clear that it’s never just about a seat on the bus, or about sitting next to a white person.

What we’re going to do tonight, we’re going to drop some of these links to the lessons in the chat, and then of course they will be sent out afterwards so people can play with them, and again, use them in your classes. But what we’re going to do is we’re going to basically just talk a little bit, as we’ve just done, and now we’re going to show another clip.

Hagopian: Well, you were just about to explain it, so we can have you live explaining it. But I’ll just quickly preface it by saying, I’m curious what Recy Taylor’s case tells us about who Rosa Parks was, and about Black women’s experience in the U.S. more broadly. Both the way white supremacy is specifically wielded against Black women, but also how Black women have organized against that white power. And, how does Recy Taylor’s case reverberate throughout history in terms of what you saw with Joan Little or even Marissa Alexander in 2017?

Theoharis: Thank you. I think the first thing is to sort of see the Recy Taylor case, and her work on it, as a microcosm of all of this work she’s doing in the 40s and 50s. And I think there’s two sides, and it’s a lot around what we would call criminal justice issues. There’s sort of two sides of that coin. One, is the wrongful incarceration of Black people, in particular Black men. Then the reverse side of that coin is the lack of protection for Black people, and particularly Black women, from white violence. Over and over, in this decade before Rosa Parks’ bus stand, she — alongside a small group of activists in Montgomery — will press for justice in many of these cases.

Here we got to see a little bit of one of those cases, which is the case of Ms. Recy Taylor. I think it shows both the breadth, as you you put it Jesse, of what the Black Freedom Struggle is about. I think we often focus on buses, lunch counters, and voting, and in fact, there was a whole range of issues that people are fighting on. Again, particularly issues we would call criminal justice issues. I think the second point that you are highlighting is the ways that people are attending to both racial and gender oppression, and the ways that we might call it intersectional oppression.

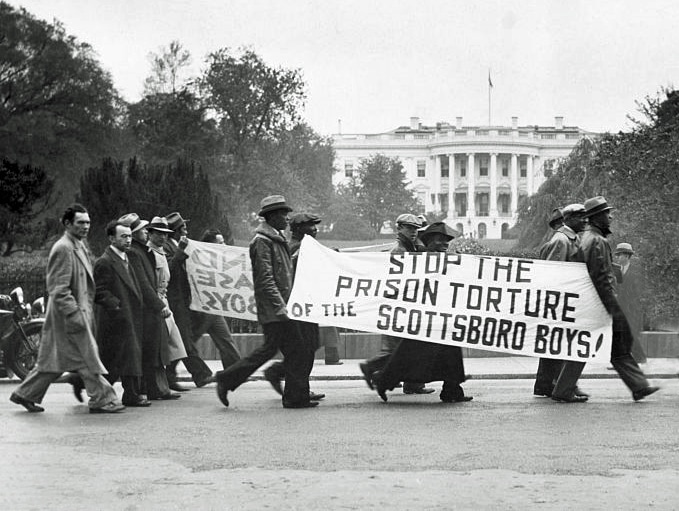

Racism is working differently towards and on Black women than it is on Black men. So we see people, and that this is not just a modern way of understanding this; people like Rosa Parks understood that as well. Part of that, again, was both fighting around cases like Scottsboro [Nine], where Black men were being wrongfully accused of sexual violence, and then the lack of protection for Black women. Fighting on that, and understanding that this [is a] long struggle. So, part of what I also think we get from this clip, and what we take to our students, is really working against the ways this is often taught, which is how many things they’re fighting on, how much they’re losing, and yet they keep fighting. I think part of what we learn about social change from a longer, bigger history of Rosa Parks is that you have to fight and you have to lay down a line, even when you can’t see that it’s going to do what you want it to do. And I think that’s a very profound lesson.

I think somebody had put in the chat, “Do you like some of these children’s books about her?” And I do not like them. The fundamental reason why I do not like them is because they do not show, and I think you can tell a kindergartener or first grader, I think you don’t have to give all the detail, but you can say, “She tried to fight this, she tried to fight this, she tried to fight this, they tried to fight this, they tried to fight this.” A first grader can understand that idea that you try things and it’s not working, keep trying them, and they’re not working. Until we start to teach that version of Rosa Parks, and that version of the Civil Rights Movement, we aren’t telling a truthful story.

We’re actually going to show one more clip before we go to break out rooms, and that is a clip that gets us to the story we’re most familiar with, which is the [Montgomery] Bus Boycott. But I think it shows the bus boycott a little bit differently than the way we’re usually given it. So, maybe we want to see that clip.

Hagopian: Jeanne, Mrs. Parks is most known for refusing to stand for the bus driver, James F. Blake, when he ordered that she relinquish her seat in the colored section to a white passenger after the whites only section was filled on December 1 1955, in Montgomery. And many of us learn this moment, everybody learns about that moment. But what is often mis-taught or left out about the Montgomery Bus Boycott is that Mrs. Parks’ long resistance, long history of resisting, helped lead to this moment. I’m also especially interested in the leading role that Black women played in organizing the boycott. Even though Martin Luther King’s career was really launched as an icon of the Civil Rights Movement, a lot of the Black women were organizing it. So hopefully you can tell us more about that.

Theoharis: I mean, this is the most familiar, this is the story we all know. Except it’s not the story we all know. And again, we have a lesson for this and I just put it in the chat. Part of what we tried to get at in the lesson is that part of how we often tell and teach the Montgomery Bus Boycott story is as a story of two people. It’s a story of Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, and somehow that turns into a boycott. I think what we can see here — and we only saw a couple minutes. The boycott section is actually about 15 minutes and we get to see a lot of different characters and how it took so many different people to both turn this act into even a one day boycott — because we want to remember it’s a one day boycott they call for, the Women’s Political Council, which is a Black women’s group in Montgomery that had been organizing.

We get to see more of that in the documentary, if you watch the full thing, they had been organizing before this, and they leap into action that night after she’s arrested. Jo Ann Robinson, who’s the head of the Women’s Political Council, runs off 35,000 leaflets that say, “There’s another woman who has been arrested on the bus.” It doesn’t say Rosa Parks has been arrested on the bus, it says another woman. And that’s because what we’re seeing is the accumulation of outrage. Claudette Colvin had been arrested in March, Mary Louise Smith had been arrested in October, and even before that there had been a trickle of people, including a trickle of women. So we have the role that women are playing in terms of bus resistance themselves. We have the Women’s Political Council, who calls that one day boycott.

I think another lesson in this is the ways that action begets a change in vision. So, it’s that night, when people feel the power of that day, that they change this one day boycott into an ongoing boycott. And I think that, again, is a really important thing for students to understand is that idea that, in some sense, being in motion changes what you can imagine is possible.

I think the last part of the Montgomery Bus Boycott story that needs to be taught is the ways that it is about an organized Black community. How they keep up a year-long boycott — and we get to see this, if you watch more of the film — is through this incredible carpool system they build, where they set up 40 pick-up stations across Montgomery, and they’re giving like 10,000 to 15,000 rides a day, and people are coordinating this and driving for it. I think that it’s this community. And Black women are fundraising to keep them [running], because this obviously requires a lot of funds and requires dispatchers. There’s all of this organization, and yet the way we tend to be taught the boycott is “just somehow it happens, and then the buses are desegregated.” And it’s just like, “No, no, no.”

So the work of it, but also the pivotal roles all these different women play in it, and yet the ways that in many ways, the only people we learn about are Parks and King — and even Parks and King are put in these very narrow boxes.

Hagopian: Yeah. And the way it’s just discussed as spontaneous, as if the Women’s Political Council didn’t run off 1000s of memos, and hadn’t been working on these issues for a long time. So, thank you for putting that in context.

Thanks for picking that clip, Jeanne. We often don’t think about the real lives of the people who have been canonized and exalted. We don’t think about their day-to-day life struggles. Only the moments that they’re famous for. And Mrs. Parks had some serious life challenges, struggling to make ends meet. So, why is it important that we learn about Mrs. Parks’ class position? And why — even after all she did to launch the Civil Rights Movement — was she not taken better care of and better supported by her comrades?

Theoharis: Again, I think if we go back to some of the master narratives, or the myths we started at the beginning of our conversation, one of the other problems with that myth of “She sits down, people rise up, things are changed,” is that it misses the person of Rosa Parks and the kind of sacrifice it really entails for her and her family.

As we saw here, she gets fired from her job five weeks in, her husband loses his job, [and] they never find steady work again in Montgomery. They leave for Detroit, and then, really, the suffering continues for many years. So, it’s a decade of suffering. And I think having to see that also helps us see, again, the length and breadth of what it takes in this sort of struggle

I think at the end of the film, Patrisse Cullors will say, “In some ways, the way we take the master narrative of Rosa Parks and the Civil Rights Movement makes it seem like fixing racism is easy.” I think that misses both the longness of the struggle, but also the personal sacrifice. And I think part of this is because she’s a woman. The kind of suffering that she is enduring, they sort of assume it’s her husband that needs to fix this. I think in some ways, it has to do with tensions between groups at that time. I think there’s lots of reasons why she kind of . . . And then she’s really proud. Telling this part of the history was really hard because she wants to get passed this period of her life, she doesn’t like to talk about it. If anybody’s read her Young Adult autobiography, it’s really not in there. So again, part of this is also [that] she doesn’t like to talk about this.

I saw someone in the chat talking about Robert Williams, and I feel like we need to clarify that. So, there is a little bit in the film about Robert Williams and about her links to Black Power. I think the way to think about Mrs. Parks and Robert Williams is a couple of things. One, is what they’re doing in Montgomery and the way they transform Montgomery’s NAACP into a more activist group is a little bit what Williams will do a decade later.

We should also just say, we skipped over this, but the Parks family are part of a long tradition of Black self-defense. They always believed in self-defense, she believed in self-defense, Raymond believed in self-defense. During the Scottsboro organizing, I mean, he was carrying. Then, fast forward to Detroit, where she actually meets Robert Williams when he comes back to the United States after he’s been in exile. And she’s part of the movement to prevent his extradition.

Interestingly, one of the things I learned when I was doing interviews was how, as he’s speaking when he comes back into the United States, and he comes back to Michigan, the Williams’ settle in Michigan, and he’s also kind of mad that people don’t recognize who she is. So his wife, Mabel Williams, told me that in a lot of speeches when they first get back to the United States, he’s saying, “People need to be recognizing Rosa Parks.” So she’s both looking out for him and raising money, and doing all these petitions around not extraditing him to North Carolina, where he’s facing charges. But also, he really sees her as this kind of hero.

I think the story people tend to tell is that she gives a eulogy at his funeral, but I think it misses all of this history they have much before then. And again, there’s some of that in the film, and some of her ties to Black Power in the film. Unfortunately, the film is only an hour and forty minutes, so there were so many things that we couldn’t fit in.

Hagopian: They’ve got to read the book, too.

Theoharis: They do have to, exactly.

Hagopian: Got to do both. Absolutely. Well, we have another clip for them, right?

Theoharis: We have another clip. I think we are having a clip on going to Detroit.

Hagopian: I think the next one is more about women. . .

Theoharis: Women, right, and the ways that women are marginalized. Yes.

Hagopian: Awesome. I love that quote from Rev. JoAnn Watson, when she says, “When you go back and check the record, those who have been labeled presidents, directors, leaders, and grand poobahs have largely been men, while the women do the work.” And then she says, “And Mother Parks did the work.” So, talk about the exclusion of women, the March on Washington, and the role of women in the Civil Rights Movement. Not just the organizing that they definitely did, but also the strategizing and the theorizing of Black women, and Mrs. Parks’ contributions to that.

Theoharis: Well, I mean, one of the ironies about the exclusion of women at the March on Washington is how much of the leadership and strategizing women are doing, even in terms of organizing the March on Washington. I think the other thing we want to be clear about is that women at the time recognized this problem. So, there are women like Anna Arnold Henchmen, like Dorothy Height, like Pauli Murray, who are protesting to [A. Philip] Randolph to [Bayard] Rustin that this is tokenism, this is unfair, that this is treating women like Black people are being treated. They’re making these criticisms at the time, and Mrs. Parks is making this criticism. She talks to one of the other women on the dais that day with her, Daisy Bates. She says to Daisy Bates, they’re talking about how they hope a change is coming. That is, all of this leadership that women have shown, and yet women are really marginalized at the March on Washington. No woman gets to speak. We get to hear the voice of Gloria Richardson in that clip. Gloria Richardson and Lena Horne kind of go off script and are taking Rosa Parks around to some international news stations. And Richardson believes this is why they get sent home. Before King even speaks, they get put in a cab and sent back to the hotel. And Richardson believes that it’s because they were going off script, because they were taking Parks around. So that’s interesting.

Gloria Richardson again, most of us, we don’t tend to learn about Richardson until college at first. Yet if we had been living in 1963, she was a household name. The movement she helped to organize in Cambridge, Maryland, it’s front page news. She’s negotiating with the Kennedy’s. Part of the irony of the erasure of women is both that it’s happening at the time, but also that some of the historical erasures really distort how important these women were in the moment. And I think, again, this gets back to what we were talking about before in terms of her suffering — that some of the suffering is also related to these gender ideas. Part of why we’re not so familiar with Rosa Parks’ ideas, is that gendered idea of who does the work and who gets used, who sits at the pulpit or on the podium.

I think we have time for one more clip, right? We’re going to look at the Detroit Uprising and think about . . . And similarly, we did a lesson that looks at the uprising, teaching racism and the movement in the north. Because one of the things, Jesse and I have been talking about this for years, but Rosa Parks really allows you to teach a whole variety of issues that aren’t necessarily in the textbook. For instance, how do you teach about the Black Freedom Struggle where you are based? Because it tends to be Montgomery, maybe Little Rock, maybe Selma. But what if you’re teaching in Portland? Or what if you’re teaching in Milwaukee? Or what if you’re teaching in Pittsburgh? And so I think, I mean, this is a specific lesson that focuses on Parks in Detroit, but I think it’s also a way into thinking about all of the movements that are happening all over the country, because racism and segregation are not just a southern problem, but a national problem.

Hagopian: What a great clip. Like we were talking about before, the way that you can teach about the Black Power movement — something that can be difficult to teach about in today’s political climate — but you can enter it through a discussion of Rosa Parks’ support for it. I love that idea. But I love the clip of Dan Aldridge saying that he was a young militant helping to organize this People’s Tribunal for the police officers who murdered those youth, and he thought that putting police on trial by the community was going to be too radical for Mrs. Parks. And then he asked her and she says, “Certainly, I’m glad you asked.” That, to me, sums up the lessons I’ve learned from you, Jeanne, about who Rosa Parks really was — just always ready to take the next step in the freedom struggle. So, talk about these Detroit Uprisings and Mrs. Parks’ reaction, and the Black Power movement.

Theoharis: I think part of what I also love about that clip from Dan Aldridge is the ways that she also really loved young people, and really loved the militancy of young people, and was willing to let young people lead. I think that’s a moment we see in the film where she’s like, “Yeah, I’m coming. I’m glad you asked.” And, you know, when I interviewed him, he said she was like, “If I can be useful, I’ll come.” This was sort of her philosophy, not that she had to tell young people what to do, but that she would come and support what they were trying to do.

It feels very modern. It feels very much like where we are today. I think it’s very useful in terms of showing our students because I think sometimes Rosa Parks is just put in this distant past. She would joke, and not joke, that people would often ask her if she knew Harriet Tubman. But I think sometimes for our students the way that the Black History Month posters of post-reification, of Black heroes, so somehow it’s just like they’re all and like black and white and in the distant past. Then you see something like this, and you’re like, “Wait a minute. These are issues we’re dealing with today.” She’s sitting on a tribunal because the police murdered three Black teenagers, and there’s no indictment and the newspapers stopped following up. And that feels very, very current. Very current.

And so, using her as a way to talk about these issues today, using all of this activism to talk about the struggles wherever we are teaching. And again, there’s lots of good resources now on so many cities. So certainly, in future discussions, if people have those questions, you can let us know and we can recommend more resources. But this has been such a fun one, right.

Hagopian: It really has, and what a great format. What a wonderful group that gathered today.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Audiogram

Historian Jeanne Theoharis discusses the organizing behind the Montgomery Bus Boycott and how that changed the trajectory of the greater Civil Rights Movement.

Resources

Many of the lessons, books, and articles recommended by the presenters and participants.

Lessons

|

The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks Teaching Guide (includes 8 lessons on Rosa Parks’ lifetime of activism) |

Books

|

In addition to Jeanne Theoharis’s The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks (Beacon Press), the following books were referenced. A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History by Jeanne Theoharis (Beacon Press) At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance — A New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power by Danielle L. McGuire (Knopf) Let It Shine: Stories of Black Women Freedom Fighters by Andrea Davis Pinkney (Harcourt) The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks: Young Readers Edition by Jeanne Theoharis and Brandy Colbert (Beacon Press) She Would Not Be Moved: How We Tell the Story of Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott by Herbert Kohl (The New Press) The Strange Careers of the Jim Crow North: Segregation and Struggle Outside of the South edited by Brian Purnell and Jeanne Theoharis with Komozi Woodard (NY Press) |

Articles and Films

|

How History Got the Rosa Parks Story Wrong by Jeanne Theoharis (The Washington Post) The Politics of Children’s Literature: What’s Wrong with the Rosa Parks Myth by Herbert Kohl (Rethinking Schools) The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks directed by Johanna Hamilton and Yoruba Richen, produced by Soledad O’Brien (film) Teaching About the Montgomery Bus Boycott by Teaching for Change (film) |

This Day In History

|

March 25, 1931: Scottsboro Nine Aug. 1, 1952: Sarah Keys Refused to Give Up Her Seat on a Bus March 2, 1955: Claudette Colvin Refuses to Give Up Her Bus Seat Nov. 27, 1955: Rosa Parks Attends Meeting About Emmett Till Dec. 1, 1955: Rosa Parks Refuses to Give Up Her Seat Dec. 5, 1955: Montgomery Bus Boycott Began Dec. 20, 1956: Montgomery Bus Boycott Prevails Aug. 30, 1967: People’s Tribunal in Detroit March 14, 1968: King Speaks About the “Other America” in the North March 10, 1972: National Black Political Convention Aug. 15, 1975: Joan Little Acquitted |

Participant Reflections

With more than 250 attendees, polls showed 50% were K–12 teachers and 15% were teacher educators. Here are more comments that participants shared in their end-of-session evaluation.

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

The significant role Black women played, yet they remained in the margins of history.

Just how multidimensional Rosa Parks was, just the fight in her for women’s rights.

Mrs. Parks was so much more than a tired lady on a bus.

To teach children that to make real change and progress, failure will happen. Specifically, when we teach about people like Rosa Parks, we need to focus on how they would try certain things and not always succeed. Progress takes time and failure.

The most interesting thing for me was Rosa’s work with women who were sexually attacked.

How other presidents, grand poobah’s, etc. took the credit for the work that women did. Just as with the military, Black people have been victims of white violence for far too long. Our bodies are not even our own in the eyes of the white male elite/white males. The way they have a voice and greed in what happens with our body is cringy and inexcusable.

What stood out during this session was the fact that Rosa Parks was involved in the first landmark case of Joan Little, the first Black woman to be acquitted after killing her assailant.

The connection to current day Greta Thunberg’s dedication to climate destruction and the same dedication Rosa Parks had to the Black Power Movement.

Reiterating the idea of the master narrative and how much of the Civil Rights Movement has been mythologized, which is so important to break those myths.

The story of Recy Taylor and the breadth and depth of Mrs. Parks’ involvement in so many elements of the freedom struggle.

How we can encourage everyone that resistance is persistence — not just one moment that makes or breaks it.

What will you do with what you learned?

This just further demonstrates the need for these materials to be in the hands of every person in the United States. The only way to battle ignorance is through education.

I would like to spend more time talking about Rosa Parks, beyond her bus moment. I see applications to many other lessons after learning about what a fighter she was throughout her life.

As a kindergarten teacher, this was a Zinn Education Project teach-in that I really felt kindergarten students could focus on. There is such a great lesson for all aspects of life in what Dr. Theoharis said about how Rosa tried x, y, and z and kept trying to fix things.

Educating myself around Black history allows me to create a space in my classroom where students of color feel seen and heard.

I am looking forward to sharing this book in my classroom, as well as the film, to re-teach Rosa Parks and the multiple ways she contributed to the Civil Rights Movement. Changing the understanding of the narrative of her work is vital to understanding her life and legacy.

I was saddened to hear that Jeanne Theoharis did not recommend any children’s books, but she explained why and it makes total sense. So as a librarian I may not be able to find quality picture books on the life of Rosa Parks. The youth edition of her book is already in our school library. One idea I had was creating short, quick facts about Rosa Parks and others and having them laminated and displayed on top of our bookshelves (which are only three feet high).

I teach a social change class at my high school, so I will bring the film as part of our exploration of the Black Freedom Struggle strategies and tactics.

I teach 5th grade and we have an advocacy unit for reading. Rosa Parks is a perfect example of a person who advocated for what she believed in and persisted for a lifetime.

I plan to watch the movie and read the book mentioned so that I can teach my 5th graders her true history during our lessons in March for Women’s History Month.

As a union leader I will share with my membership and the Racial & Social Justice Team in our district.

I feel that this film and book will fit in nicely with the curriculum I teach students about the Civil Rights Movement.

Plan a movie screening with our Women’s Empowerment Group, students, and mentors. I will follow up with a Zinn Education Project lesson and end with some personal narratives.

I’m currently on a school board. I want to share this with my fellow members, as well as the faculty at our school. Our educators need to know the truth to be able to #TeachTruth.

Presenters

Jeanne Theoharis is a distinguished professor at Brooklyn College. She is the author or co-author of nine books and numerous articles on the Civil Rights and Black Power movements and the politics of race and education. Her books include the award-winning titles The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks and A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing, and on the staff of the Zinn Education Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn