The following essay was presented at the Howard Zinn Read-In held at Purdue University on November 5, 2013. This is a condensed version of a chapter on Zinn in a forthcoming book, On Doing History from the Bottom Up, published by Haymarket Books in 2014.

The following essay was presented at the Howard Zinn Read-In held at Purdue University on November 5, 2013. This is a condensed version of a chapter on Zinn in a forthcoming book, On Doing History from the Bottom Up, published by Haymarket Books in 2014.

____________________________________

If you are like me, and I think you are, you may be expecting something like one of the old Wobbly free speech fights. I will say, “We hold these truths to be self-evident,” after which I will be arrested. One of you will take my place and declare, “That all men and women are created equal,” after which the gendarmes will come for you as well. And so on, page after page of the People’s History, until the West Lafayette municipality decides it is too expensive to keep us all in jail.

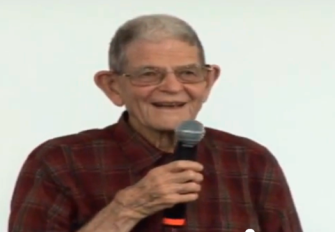

Just in case there is some delay in this anticipated rerun of ancient events, I offer a few comments about the life of our departed colleague and comrade.

Howard was born in 1922, and what we might consider the first part of his life included service as a bombardier in the United States Air Force. The GI Bill, together with working the 4 p.m. to midnight shift in a Manhattan warehouse, made it possible for Howard to earn master’s and PhD degrees at Columbia University.

A second period of Howard’s life began with the Zinns’ arrival at Spelman College, a college in Atlanta for African American women, in August 1956. During this part of his life, Howard taught history, began his years of service as an adult advisor to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and wrote a book about overcoming racism.

Finally, there is the long time from June 1963 to Howard’s death in January 2010. In these years Howard and his family lived in a Boston suburb, he taught in the political science department at Boston University, and he wrote Vietnam: The Logic of Withdrawal, The Politics of History, and his best-selling People’s History of the United States. He also took part in innumerable demonstrations, wrote countless articles, and endlessly gave talks in his inimitably communicative manner.

The Repentant Bombardier

The Howard Zinn who chronicled SNCC’s striving to overcome racism, who wrote A People’s History and shepherded it through several editions, was a steadfast advocate for an unchanging point of view.

But the first segment of Howard’s life exhibited an equally dramatic reversal of perspectives. During World War II, Howard was so eager to get into combat that he gave up a shipyard job that would have kept him safe until the end of the war. Then he arranged with his draft board to “volunteer for induction,” even requesting and receiving permission to mail his induction notice to himself in order to be sure it would arrive. During flight training, Howard was anxious to go into action and “traded with other bombardiers to get on the short list for overseas.”

But by the time he was discharged, Howard was beginning to be not so sure about the description of his service as “honorable.” He put into a folder some photos, old navigation logs, and other momentos, his Air Medal and ribbons with two battle stars. Then, without thinking, he wrote on the folder: “Never again.”

Howard Zinn had become an early example of today’s troubled combatants in the United States military who volunteer for wartime service but then find it more and more difficult to take part in conduct they perceive to be “war crimes.” A serviceman or woman so situated will find it enormously difficult to be considered a “conscientious objector.” Under present law and regulations, to be recognized as a “conscientious objector” the applicant must oppose “war in any form” on the basis of “religious training and belief.” This definition of conscientious objection (CO), negotiated before World War II by several small Protestant sects and the federal government, is an example of what Herbert Marcuse called “repressive tolerance.” There will never be enough members of the Amish, the Brethren, the Hutterites, or the Quakers to constitute a serious obstacle to warmaking by the United States. The government can point to those whose youthful church attendance and tender consciences qualify them to be recognized by the law as COs. The far larger number who do not meet these requirements register their objection by suicide, alcoholism, bursts of inexplicable sadism, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Howard Zinn had become an early example of today’s troubled combatants in the United States military who volunteer for wartime service but then find it more and more difficult to take part in conduct they perceive to be “war crimes.” A serviceman or woman so situated will find it enormously difficult to be considered a “conscientious objector.” Under present law and regulations, to be recognized as a “conscientious objector” the applicant must oppose “war in any form” on the basis of “religious training and belief.” This definition of conscientious objection (CO), negotiated before World War II by several small Protestant sects and the federal government, is an example of what Herbert Marcuse called “repressive tolerance.” There will never be enough members of the Amish, the Brethren, the Hutterites, or the Quakers to constitute a serious obstacle to warmaking by the United States. The government can point to those whose youthful church attendance and tender consciences qualify them to be recognized by the law as COs. The far larger number who do not meet these requirements register their objection by suicide, alcoholism, bursts of inexplicable sadism, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

In his autobiography, Howard offers some important clues as to why his outlook on war began to change during his service as a bombardier.

Howard had made friends with a gunner in another crew, who, like himself, read books and was interested in politics. One day his friend said, “You know, this is not a war against fascism. It’s an imperialist war.” Startled, Howard responded, “Then why are you here?” and his friend replied, “To talk to guys like you.” Two weeks later his friend’s plane was shot down and the whole crew killed.

Then when the war was almost over, the briefing officer said that they were going to bomb a French town named Royan. A few thousand German soldiers had retreated to Royan. They weren’t fighting, just waiting for the war to end. The planes in Howard’s squadron were not going to carry their usual load but, instead, 30 one-hundred pound canisters of “jellied gasoline.” The town of Royan was decimated, the many victims French as well as German. Only long after the war did Howard recognize that this was an early use of napalm.

Howard Zinn’s last public speech was titled “Three Holy Wars.” It was delivered at Boston University on November 11 (the day that in my childhood we called “Armistice Day”), 2009. The three “holy wars” were the American Revolution, the Civil War, and World War II.

Howard asked whether the American Revolution was necessary. “How about Canada?” he said. “They are independent of England. They did not fight a bloody war. It took longer. Sometimes it takes longer if you don’t want to kill.”

A kind of electric shock went through me as I read those words. I recalled how in the 1960s Howard had been so careful to distinguish his views from what he called the “absolutism” of pacifists. He seemed to be espousing in the last weeks of his life a sort of de facto pacifism, a position that amounted to pacifism even if you used different words.

A kind of electric shock went through me as I read those words. I recalled how in the 1960s Howard had been so careful to distinguish his views from what he called the “absolutism” of pacifists. He seemed to be espousing in the last weeks of his life a sort of de facto pacifism, a position that amounted to pacifism even if you used different words.

Proceeding to the Civil War, Howard asked essentially the same thing. Yes, slavery had been abolished, but did that require the deaths of 600,000 Union and Confederate soldiers? (Since Howard’s death, a new survey based on the number of “missing males” in census data has raised the estimated number of Civil War fatalities to 750,000.) Everywhere else in the Western Hemisphere, Howard insisted, slavery had been abolished without a bloody civil war.

He went on to his own war, World War II. Howard’s essential message was that when you bomb from 30,000 feet,

this is modern warfare, you do things from a distance, it’s very impersonal. You just press a button and somebody dies. You don’t see them. . . . I didn’t see any human beings. I didn’t see what was happening below. I didn’t see children screaming, I didn’t see arms being ripped off people. No. You just drop bombs. You see little flashes of light down below as the bombs hit. That’s it. And you don’t think

Was this history? Repentance? Prophetic denunciation? All of the foregoing? This vignette by a participant in saturation bombing by Allied warplanes is indeed history from below (as well as from high above). Perhaps Howard Zinn exemplified thereby something just as powerful and memorable as the unforgettable words he wrote about persons he had never known, like Christopher Columbus.

Overcoming Racism

Howard Zinn and I were colleagues at Spelman College in the academic years 1961-62 and 1962-63. Our families lived on campus, around the corner from each other in the same building.

It strikes me as strange that so-called “whiteness theory,” while no doubt a form of history from the bottom up, seems wholly preoccupied with why some white workers become racists and devotes almost no attention to how racism can be overcome. It was otherwise in Atlanta in the early 1960s. During those years the inevitable subject of conversation was how a society so saturated with racism as the southern United States might free itself from that miasma. The Spelman College campus was roiled by conflict arising when the young ladies enrolled there went downtown to attempt to use segregated public libraries, to picket local restaurants and department stores, or to sit in the “whites only” gallery at the state legislature.

In a typical incident illustrative of the crisis atmosphere, I was awakened one night by a phone call to the effect that a friend who taught at Atlanta University, his wife, and their two young daughters, had all been arrested while peacefully picketing. Morris and Fannie were in the city jail downtown. Would I go to the juvenile detention facility on the city outskirts and bail out the two girls?

Howard explored the American dilemma of racism in a book largely forgotten today, The Southern Mystique.

Howard explored the American dilemma of racism in a book largely forgotten today, The Southern Mystique.

The book’s central argument is made clear in a journal Howard kept (now in the Zinn Papers at New York University) while drafting this book. He was simultaneously beginning to do oral histories for his next book, SNCC: The New Abolitionists. Thus the entry on January 10, 1963, reports: “Ran into Ruby Doris Smith — she finishes school this semester, will do fieldwork for SNCC thereafter. Told her want to tape her experiences.”

On that same date Howard described a town hall meeting in which he took part together with Eugene Patterson, editor of the leading Atlanta newspaper; Macon mayor Ed Wilson; and Sam Williams, a black professor. Howard wrote in his journal, “Both Sam and Patterson said at different points that [we] must change Southern white behavior before [we can] change his mind — squares exactly with what I’ve been writing about.”

The next day, January 11, the journal reports the visit of a Princeton sociologist named Berger. On January 19, after interviewing Julian Bond at the Zinns’ apartment and “concentrated talk with Negroes in all sorts of situations,” Professor Berger “came over for a last chat before departure.” Howard and his guest “disputed a little about the future,” Howard records.

He sees, after legal desegregation, a plateau, no real improvement, with whites continu[ing] to be prejudiced and no indication of change. . . . My argument: Yes, it seems strong, and it is at the moment, but it can change quickly — with contact. When housing and jobs become open, when white salesmen begin to have lunch — thru business necessity — with Negroes and stay at the same hotel with them, and so on — I cited my warehouse experience.

What did Howard mean by his “warehouse experience”? After the Air Force, Howard used the GI Bill to earn degrees at NYU and Columbia, and while doing so worked the 4 to 12 shift at a Manhattan warehouse, “loading heavy cartons of clothing onto trailer trucks.” In his autobiography, Howard explains the relevance of this experience to the theme of his conversation with Professor Berger. The warehouse crew included, along with several whites, a black man and a Honduran immigrant. Working together, they came to respect one another as equals.

In Howard’s view “equal-status contact” over a period of time, as among members of the warehouse crew, was what would cause racial attitudes to change. The Southern Mystique presents a sophisticated rationale for this approach. Persons inclined to dismiss Howard Zinn as a shallow popularizer should take a look at the “Bibliographical Notes” to his book. Here one finds works of history, like Stanley Elkins’ Slavery; The Strange Career of Jim Crow by C. Vann Woodward; W. E. B. Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folk; From Slavery to Freedom by John Hope Franklin; and W. J. Cash, The Mind of the South. Howard also cites sociologists Ross, Cooley, Mannheim, Merton, and Franklin Frazier, and psychologists Harry Stack Sullivan, Kurt Lewin, and Gardner Murphy.

Howard’s logic goes as follows. Everyone has a hierarchy of values. For many persons, racism may be one such value but it is unlikely to be the thing that anyone cares about most. Change the external requirements of daily life so that whites must engage in equal-status contact with blacks in order to achieve their highest priorities, and over time, racist attitudes will change in response.

In his autobiography, Howard tells us how this idea first occurred to him. After he joined the Air Force and finished training, Howard found himself on a luxury liner headed for Europe. There were 16,000 troops on board. The 4,000 who were black “slept in the depths of the ship near the engine room” and ate last, in, so he comments in A People’s History, “a bizarre reminder of the slave voyages of old.”

On the fifth day at sea there was a mix-up. The last shift poured into the dining room before the previous shift had finished eating, filling in wherever white men had left. A white sergeant, sitting next to a black man, called out to Howard (who was by then a second lieutenant), “Get him out of here until I finish.” Howard refused and the sergeant, apparently caring more about his food than about who sat next to him, finished his meal.

Howard’s entry for March 3, 1963, offers the journal’s most extended explanation of this strategy for overcoming racism. The YWCA had brought 80 Negro and white college students from all over the South to a conference in Gatlinburg, Tennessee. Howard was invited as a presenter. Regardless of “all the nonsense associated with Y conferences,” he commented in his journal, it was a “revolutionary act, really a marvelous thing to see. . . . Two days of living together are worth two decades of reading or talking about ‘good race relations.’” The young women didn’t need to “talk about these things, just live them.”

Working Class Self-Activity

As in the title of his best-known book, Howard Zinn often invoked “the people.” Indeed, he appears to have set up the contrast of the wealthy 1 percent with the rest of us 10 years before the Occupy movement made the comparison famous, after Howard’s death.

But the core of Howard’s personal experience of the power of the people was a series of immersions in specifically working-class collective action. I believe that a lifelong commitment to working class self-activity is at the heart of Howard Zinn’s radicalism. In contrast to the diffuse mutual aid of “the people,” or temporary coalitions of soldiers and prisoners against repression, the solidarity of persons who work together remains the core of resistance to capitalism and prefigures a better society.

But the core of Howard’s personal experience of the power of the people was a series of immersions in specifically working-class collective action. I believe that a lifelong commitment to working class self-activity is at the heart of Howard Zinn’s radicalism. In contrast to the diffuse mutual aid of “the people,” or temporary coalitions of soldiers and prisoners against repression, the solidarity of persons who work together remains the core of resistance to capitalism and prefigures a better society.

One can follow this thread from beginning to end of Howard’s experience.

Hard labor as an apprentice shipfitter for three years during World War II was Howard’s “introduction to the world of heavy industry,” he tells us. “What made the job bearable was the steady pay and the accompanying dignity of being a workingman, like my father.” But “most important” for Howard was that he found among his workmates “a small group of friends, fellow apprentices — some of them shipfitters like myself, others shipwrights, machinists, pipe fitters, sheet metal workers — who were young radicals, determined to do something to change the world.”

What they decided to do, since they were excluded from the craft unions of the skilled workers, was “to organize the apprentices into a union, an association.” Three hundred young workers joined. Howard says that this was his “introduction to actual participation in a labor movement.” He and his co-workers, Howard writes, were doing “what working people had done through the centuries, creating little spaces of culture and friendship to make up for the dreariness of the work itself.”

Howard and three others were elected to be officers of the apprentices’ association. “We met one evening a week to read books on politics and economics and socialism, and talk about world affairs.”

After the war, at the warehouse, Howard shared the following experience with the other truck loaders.

We were all members of the union (District 65), which had a reputation of being “left-wing.” But we, the truck loaders, were more left than the union, which seemed hesitant to interfere with the loading operation of this warehouse.

We were angry about our working conditions, having to load outside on the sidewalk in bad weather with no rain or snow gear available to us. We kept asking the company for gear, with no results. One night, late, the rain began pelting down. We stopped work, said we would not continue unless we had a binding promise of rain gear.

The supervisor was beside himself. That truck had to get out that night to meet the schedule, he told us. He had no authority to promise anything. We said, “Tough shit. We’re not getting drenched for the damn schedule.” He got on the phone, nervously calling a company executive at his home, interrupting a dinner party. He came back from the phone. “Okay, you’ll get your gear.” The next workday we arrived at the warehouse and found a line of shiny new raincoats and rain hats.

These personal experiences stood by Howard when, in A People’s History, he came to the worker self-activity of the 1930s. Howard did not agree with typical liberal celebration of the creation of the CIO by John L. Lewis. He insists that “it was rank-and-file insurgencies that pushed the union leadership, AFL and CIO, into action.” He offers a detailed and affectionate description of the first sit-down strikes and how the tactic spread. Then he writes:

The sit-downs were especially dangerous to the system because they were not controlled by the regular union leadership. . . . Unions were not wanted by employers, but they were more controllable — more stabilizing for the system than the wildcat strikes, the factory occupations of the rank and file. In the spring of 1937, a New York Times article carried the headline “Unauthorized Sit-Downs Fought by CIO Unions.” The story read: “Strict orders have been issued to all organizers and representatives that they will be dismissed if they authorize any stoppages of work without the consent of the international officers. . . .” The Times quoted John L. Lewis, dynamic leader of the CIO: “A CIO contract is adequate protection against sit-downs, lie-downs, or any other kind of strike.”

Summing up, Howard described the National Labor Relations Act, and the structure and practice of the new CIO trade unions, as “two sophisticated ways of controlling direct labor action.” The CIO might be “a militant and aggressive union,” yet it would “channel the workers’ insurrectionary energy into contracts, negotiations, union meetings, and try to minimize strikes, in order to build large, influential, even respectable organizations.” Accordingly, Howard concluded that the history of the 1930s seemed to support the analysis of Richard Cloward and Frances Fox Piven, who argued in their book Poor People’s Movements “that labor won most during its spontaneous uprisings, before the unions were recognized or well organized.”

Once again as a professor at Boston University, Howard confronted personally issues arising from the efforts of workers to organize themselves. To begin with, teachers like Howard pursued the right to organize. In addition, responding to the arrogant administration of President John Silber, campus workers of all kinds, such as clerical workers, librarians, and staff at the nursing school, also insisted on their rights under the National Labor Relations Act. Howard consistently advocated not only aggressive self-activity by teachers but also solidarity with other groups of less prestigious workers at the university.

Once again as a professor at Boston University, Howard confronted personally issues arising from the efforts of workers to organize themselves. To begin with, teachers like Howard pursued the right to organize. In addition, responding to the arrogant administration of President John Silber, campus workers of all kinds, such as clerical workers, librarians, and staff at the nursing school, also insisted on their rights under the National Labor Relations Act. Howard consistently advocated not only aggressive self-activity by teachers but also solidarity with other groups of less prestigious workers at the university.

On one occasion, in 1979, all of the campus groups that had organized unions went on strike. The issue for faculty was that after a contract was agreed to, the university had reneged.

Anyone who has experienced such a situation knows how hard it is to rekindle the collective will to take risky action after a dispute has apparently been resolved. At the annual meeting of the Organization of American Historians after Howard’s death, one of his colleagues described a meeting of faculty activists the evening they learned of the administration’s double cross. Howard, one of the co-chairs of the faculty’s strike committee, was not present when the meeting began. The mood was glum. Then Howard appeared, laden with poster board and magic markers. A strike went forward. Howard’s responsibility, so he says, was “to organize the picket lines at the entrance to every university building, to establish a rotation system among the hundreds of picketers.” After nine days of picketing and endless meetings, the university gave in.

Then a second issue presented itself. While teachers were out on strike and walking picket lines, secretaries also struck. For a time “we all walked the picket lines together, a rare event in the academic world.” Even after the teachers had signed a contract that banned sympathy strikes, Howard and a few other faculty members urged that teachers should refuse to go back to work until the administration agreed to a contract with the secretaries. Teachers as a group could not be persuaded. Howard and four others proceeded to hold their classes out of doors. President Silber threatened them with discharge but after a storm of protest, backed down.

Howard ended his last class early, then led those in attendance to a picket line in front of the school of nursing.

This deep sense of solidarity with the refusal to quit on the part of struggling families like that in which he grew up is one reason that persons who knew Howard, either personally or through his books, feel such affection for him. The text that, more than any other, elicits such solidarity and affection for Howard Zinn on my part, is the final scene in the first version of his play about Emma Goldman, titled “Emma.”

This deep sense of solidarity with the refusal to quit on the part of struggling families like that in which he grew up is one reason that persons who knew Howard, either personally or through his books, feel such affection for him. The text that, more than any other, elicits such solidarity and affection for Howard Zinn on my part, is the final scene in the first version of his play about Emma Goldman, titled “Emma.”

Let me paraphrase. A group of aged anarchists have gathered at their favorite Lower East Side cafe in New York City. Something has stirred the embers. They are actually going to do something: They are going to distribute a leaflet early the next morning.

A man enters the café dressed in a shabby overcoat. Is it possible? Yes! It is Alexander Berkman, released from federal prison after many years of confinement for his attempt to assassinate Henry Clay Frick of U.S. Steel during the Homestead strike.

His comrades crowd around him. But Berkman asks: What were you talking about when I came in? They respond: It doesn’t matter! This is your first taste of freedom, Sasha! Relax! Be happy!

No, Berkman persists, I want to know. His colleagues answer: Well, if you must know, we are planning a leaflet distribution tomorrow morning. Berkman says: And do you have someone to distribute leaflets at every location where you plan to pass them out? Reluctantly, they admit: For every location except one; we’re still looking for someone for Broome Street.

Berkman says: I’ll take Broome Street. And the curtain falls.

Howard Zinn, presente.

__________________________________________________________

Watch the full event below. To watch Staughton Lynd’s presentation, forward to 1 hour, 44 minute mark or click here.

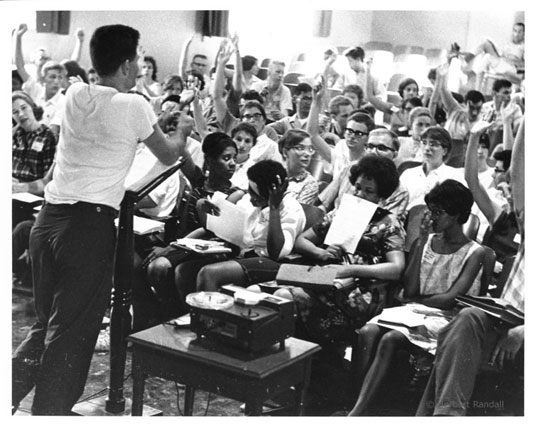

Staughton Lynd speaks with Freedom School teachers in Oxford, Ohio, 1964.

Staughton Lynd taught history at Spelman College and Yale in the 1960s and coordinated the hugely successful Freedom Schools during the Mississippi Summer Project of 1964. After moving to New Haven, Lynd became a spokesperson for opponents of the Vietnam War. As a result of these activities, Lynd was denied work as a university professor and he and his wife became lawyers. Since 1976 they have lived in Youngstown, Ohio, working with and representing local victims of deindustrialization, and prisoners confined at Ohio’s first super-maximum security prison. Read more in From Here to There: The Staughton Lynd Reader.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn