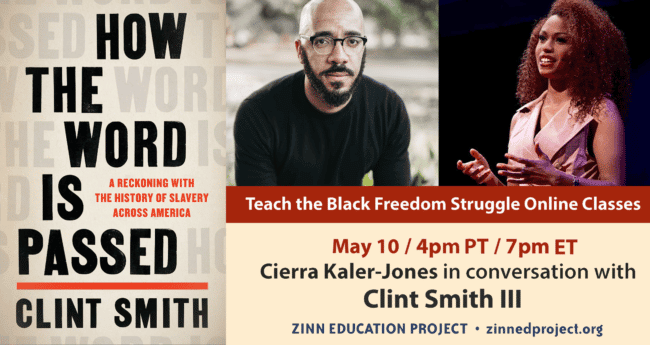

Author and educator Clint Smith joined the Zinn Education Project on May 10, 2021 for a conversation about his new book, How the Word Is Passed, an examination of how monuments and landmarks represent — and misrepresent — the central role of slavery in U.S. history and its legacy today. Smith is a poet, staff writer at The Atlantic, and teaches writing and literature in the D.C. Central Detention Facility. Cierra Kaler-Jones interviewed Smith and led a conversation about slavery, memory, and how white supremacy distorts our environment.

This online history class is part of the Teach the Black Freedom Struggle campaign. The Zinn Education Project is developing lessons to bring How the Word Is Passed, an essential book, to the classroom.

Here are a few reactions from the participants:

We are teaching historical truth, not “incorporating Black history.”

It was very powerful and helpful to be reminded that we are teaching a more truthful version of history by talking about race, racism, and slavery.

The Freedom Bank story — amazing and so revealing of the way Black people (and other POC) are taken advantage, related to way we can easily feel we are the reason for our victimization… which then lessens our resistance to that victimization. Yes!

There is more to history that effected Black generational wealth besides redlining. Our state standards need to be updated to include requirements for teaching the history of racism in U.S.

There were a plethora of free Black communities in New Jersey since the time of the American Revolution. I teach and live in New Jersey and did not know this.

Find highlights of the session, a video recording of the class (except breakout room segment), recommended resources, and more participant feedback.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

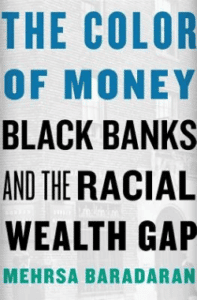

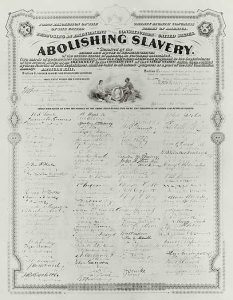

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion. Cierra Kaler-Jones: We are so lucky to be joined by Clint Smith, and I’m so honored to be able to facilitate and host this conversation. Dr. Clint Smith is a teacher, a poet, a journalist, a father, and I hear that he’s also a soccer fan, and author of How the Word Is Passed, which will be released on June 1 [2021]. I highly, highly, highly suggest that you all pre-order this book at your local independent bookstore. Clint, as we get started, I first want to just start by saying thank you. As I read through the passages in your book, I was transported to so many places beside you, and you do a fabulous job of just carefully weaving together history and the present, providing a roadmap for how we can have critical conversations and make connections to how we grapple with enslavement. So to begin, you shared in a teacher workshop that you began writing this book as a series of poems, and I would love it if you would open up our conversation this evening with your poem about growing up surrounded by the iconography of the Confederacy. Clint Smith: Growing up, the iconography of the Confederacy was an ever present fixture of my daily life. Every day on the way to school, I passed a statue of P. G. T. Beauregard riding on horseback, his Confederate uniform slung over his shoulder and his military cap pulled far down over his eyes. As a child, I did not know who P. G. T. Beauregard was. I did not know he was the man who ordered the first attack that opened the Civil War. I did not know he was one of the architects who designed the Confederate battle flag. I did not know he led an army predicated on maintaining the institution of slavery. What I knew is that he looked like so many of the other statues that ornamented the edges of the city. These copper garlands of a passed that saw truth as something that should be buried underground and silenced by the soil. After the war, the Sons and Daughters of the Confederacy reshaped the contours of treason into something they could name as honorable. They called it the Lost Cause, and it crept its way into textbooks that attempted to cover up a crime that was still unfolding. They told us that Robert E. Lee was an honorable man, guilty of nothing but fighting for the state and the people that loved, that the southern flag was about heritage and remembering those slain fighting to preserve their way of life. But, the thing about the Lost Cause is that it’s only lost if you’re not actually looking. The thing about heritage is that it’s a word that also means I’m ignoring what we did to you. I was taught the Civil War wasn’t about slavery, but I was never taught how the declarations of Confederate secession had the promise of human bondage carved into stone. I was taught the war was about economics, but I was never taught that in 1860, the four million enslaved Black people were worth more than every bank, factory, and railroad combined. I was taught the Civil War was about states’ rights, but I was never taught how the fugitive slave who couldn’t care less about a border spelled Georgia and Massachusetts the exact same way. It’s easy to look at a flag and call it heritage when you don’t see the Black bodies buried behind it. It’s easy to look at a statue and call it history when you ignore the laws written in its wake. I come from a city abounding with statues of white men on pedestals and Black children playing beneath them. When we play trumpets and trombones to drown out the Dixie song that’s still whistled in the wind. In New Orleans, there are over one hundred schools, roads, and buildings named for Confederates and slaveholders. Every day, Black children walk into buildings named after people who never wanted them to be there. Every time I return home, I drive on streets named for those who would have wanted me in chains. Go straight for two miles on Robert E. Lee; take a left on Jefferson Davis; make the first right on Claiborne and go straight for two miles on the general who slaughtered hundreds of Black soldiers who were trying to surrender; take a left on the president of the Confederacy who made the torture of Black bodies the cornerstone of his new nation; make the first right on the man who permitted the heads of rebelling slaves to be put on stakes and spread across the city in order to prevent the others from getting any ideas. What name is there for this sort of violence? What do you call it when the road you walk on is named for those who imagined you under a noose? What do you call it when the roof over your head is named after people who would have wanted the bricks to crush you? Kaler-Jones: Thank you, thank you, thank you for sharing that with us. I want to just highlight too that I saw that an excerpt of your chapter on Blanford Cemetery about the Lost Cause is on the cover of The Atlantic that came out today. So we’ll post a link in the chat box so that everyone has an opportunity to have access to that as well. In that poem I love how you talk about monuments and statues and streets as visual literacy, the narratives, the stories that we tell. So, speaking of narratives, can you tell our audience about one of the chapters in the book and how it compares to what young people learn or don’t learn in textbooks? Particularly, I know that chapter on New York was eye-opening for me growing up in New Jersey, since it’s not a place that is usually included in lessons on enslavement. Smith: I mean, certainly part of what I wanted to do was, one, most of the places that are documented in the book are in the South, because of the oversaturation of slavery in the South throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. But I also wanted to ensure that I wasn’t writing a book that was singularly in the South, as if to depict slavery as something that singularly happened in southern states. As we know, New York City was the second largest labor port in the country for a long time, after Charleston, South Carolina. So the history, part of what I wanted to do in going to a place like New York City, in going to a place like Dakar, Senegal, and going to a place like Galveston, Texas — where so much of what we hear about Texas is tied historically to cowboys and westerns, but it’s fascinating for me to think about all these westerns and to consider who wasn’t in them — and I was like, “Well, who helped construct and build and lay the great infrastructural groundwork for so much of what we saw in these films?” So, I mean, New York City is an example. I remember, as I was working on the book, one thing that I realized that I didn’t know — that I certainly hadn’t been taught in school — was the Statue of Liberty’s relationship to slavery. In the sense that the Statue of Liberty — I was always taught about it in conjunction and in relationship with Ellis Island and it being this massive symbol meant to, one, demonstrate the relationship between America and France and that sign of friendship, and two, how it came to symbolize the promise of American democracy and welcoming, that it was right next to Ellis Island, welcoming new immigrants into this experiment in democracy that never existed in the way that it did in the new world. But [Edouard de] Laboulaye, who was a Frenchman who conceptualized the Statue of Liberty, was the leader of the French anti-slavery society. Many historians believe that the Statue of Liberty was intended as a gift to celebrate the abolition of slavery following the end of the Civil War. But, over time, the meaning of the statue changed, and even the design of the statue changed. The original design of the statue, instead of having a book in Lady Liberty’s hand, was actually shackles that were being broken apart to symbolize the abolition of slavery, to symbolize emancipation, and they were moved to be in a more inconspicuous place, to be hidden beneath the robe around her foot in a way that I remark in the book that you can’t even see them unless you’re in a helicopter or a plane flying overhead. That was striking to me because it almost is a microcosm for the way that this country’s history attempts to rewrite itself in order to push slavery to the periphery. I think all the time about my my friend and mentor Ta-Nehisi Coates, who said that slavery was not a bump in the road, it was the road itself. That we tried to make slavery seem as if it was this thing that was peripheral to the American experience, as if it was something that were an accident, something that we did along the way, but everything else was great. When, in fact, what we know, like in 1860, that historian David Blight writes, as I mentioned in the poem, the four million enslaved Black people were worth more than every bank, factory, and railroad combined. Worth more than all of the manufacturing that existed in 1860 were the bodies of enslaved people. So the reason the United States exists as a global economic superpower is obviously and statistically intrinsically linked to the history of enslavement and the labor that was extracted from that. So, I thought that the Statue of Liberty was a really fascinating symbol, a microcosm for a much larger phenomenon that happens in American history. But it wasn’t even just in New York. I mean, part of what animated this book was thinking about all the things that I hadn’t been taught in my own elementary school. So, with my own K–12 education, and I write about this in the book, I think I’ve talked about this in the Galveston chapter, but for so much of my childhood I felt a sort of psychological, emotional, and intellectual paralysis, in which people were telling me all of these things about what was wrong with Black people, explicitly or implicitly. I grew up in New Orleans and New Orleans was called the murder capital of the nation, it was called the place that incarcerated more people per capita than China and Iran and Russia and all these authoritarian governments. The message meant — so many of the messages both, again, implicit and explicit, around this majority Black city and the Black people in it — was suggesting that the reason these communities look the way that they did is because of something Black people have done themselves, or failed to do themselves. I grew up not having the language, or the toolkit, with which to name and identify and understand the reason our contemporary landscape of inequality looks the way that it does today. It’s not because of the people in these communities, but it’s because of what has been done to these communities, generation after generation after generation. I think often of this James Baldwin quote, in his essay “A Talk to Teachers,” which is a speech that he gave in 1963 to a group of New York City educators. He says a lot in that essay, but one of the things that he says that really stood out for me was that as educators, our job is to teach the Black child that although the world tells them that they are criminal, it is our duty to help them understand that it’s not the child who’s criminal, but it is, in fact, the society that created the conditions that that child grew up in that is actually the criminal. It is the history, it is the socio-political landscape, it is everything that came before that made it so that that child grew up in a social and economic context in which their hard work isn’t allowed to manifest itself in the same way that somebody who grows up surrounded by all the resources and things they don’t need. So, when I’m writing about growing up around these statues in New Orleans, I’m thinking about how in eighth grade Louisiana history class nobody ever told me who P. G. T. Beauregard was, that he was the man who basically ordered the shot that opened the Civil War. Nobody ever told me about Robert E. Lee as an enslaver, that he had his slaves beaten and filled their wounds with brine after they ran away. All I knew was that he was this man on a 60 foot pedestal in this traffic circle that I drove past every day on the way to school. I was just thinking about all the things, the landscape, that I grew up around both symbolically and politically, and I wanted to write something that tried to fill in those gaps, that I wish I had growing up. As you all know, you all educators who are deeply committed to this work, part of the insidiousness of white supremacy is that it takes something like the Confederacy, a treasonous army predicated on maintaining and expanding the institution of slavery, and it turns it, it makes it seem as if it’s an ideological statement rather than an empirical one, rather than one that is actually grounded in primary source documents, rather than one that is actually grounded in the evidence of what they said for themselves. I think, for me, it was really important to consider how the things that I wish I had been taught would have given me were not political, were not ideological. They were holistic, they were honest, and they were providing me with a wider range of information with which to more effectively make sense of everything that I was seeing. So, that’s a long way of saying every chapter had something that either ran counter to what I had been taught growing up or filled in a gap. And sometimes you find gaps that you didn’t even know were there, gaps you didn’t even know existed. Kaler-Jones: That’s actually a perfect segue into my next question. In your chapter on Monticello, Teresa, one of the tour guides said, “We’re not changing history, we’re telling the full history by telling the full story, more of the story of everyone who lived here, not just certain people who are able to tell their stories.” You also talk more about how the history of enslavement is the history of the United States, and you referenced what Ta-Nehisi Coates said, so what are you making of the current wave of attacks on teaching the truth about history, the very history that your book is shining a light on? Smith: It is very clear that there is one political party in this country who is devoid of ideas, who is devoid of, in many ways, compassion and empathy. They predicate the entire basis and platform of their political party on a culture of fear, on a culture of lies, on a culture of misrepresentation, and in creating social and cultural battles that are going to evoke and elicit fear from the base of the party, because that is the only currency that they have. It’s not ideas, it’s not things that will make the country better. It is at this moment predicated on lighting fires of cultural battles that are meant to — whether it be in the context of transgender children, whether it be in the context of teaching slavery, whether it be in the context of misrepresenting different elements of history — to scare people into thinking that the world that they have known is changing in a way that they should be frightened of. It’s unfortunate because you want two parties that are operating in good faith, and what you want are people who are trying to figure out the policies that they genuinely believe will best help people, the American people and people across the world. It is indicative of absolute cravenness and cowardice, and I think that our job is to push back against it. Again, the insidiousness of this is that it turns these empirical statements into ideological ones. It’s not to say that we all don’t bring our own politics into the classroom, we don’t bring our political dispositions and sensibilities. But it is not to teach the history of slavery, to teach the history of Jim Crow apartheid, to teach the history of Indigenous removal, to teach the history of Japanese American internment, to teach the history of persecution that LGBTQ folks have experienced. It is not an ideological endeavor. It is one that is honest about what this country has been and what this country has done so that we can more effectively repair the harm that has been done against these communities, to build a more just and equitable society. What we need to do is continue to push back against it, continue to reject it, and continue to reject the lie that’s propagated by even thoughtful people, whether they be administrators or what have you, that teaching this history with rigor and centering this history in our classrooms, and using critical pedagogy in our classrooms, is somehow at odds with intellectual rigor. That’s not even coming from the right, that’s part of the lie that we’re told even from those who are empathetic to the things that we’re thinking about. It’s this idea of ‘this is great, but we don’t want to compromise the academic or scholarly rigor and depth of the work,’ or ‘is this aligned with common core or not?’ As I’ve argued in an essay before, I think it is far more rigorous, if you’re teaching about Thomas Jefferson, to demand that a student hold the complicated truths of Jefferson at once, instead of pretending that Jefferson is the sort of mythic figure that he has often been presented to us as, and certainly that he was presented to me as in my K–12 education. I think that part of what we need to do is consider what does it mean that Jefferson was very smart and also very racist? What does it mean that he wrote in one document that all men are created equal and wrote in another document, Notes on the State of Virginia, that enslaved Black people are “inherently inferior to whites in both endowments in body and mind?” What does it mean that he wrote one of the most important documents in the history of the Western world, the Declaration of Independence, and also owned and enslaved over 600 people over the course of his lifetime, including four of his own children? To ask our students to hold that complexity and to wrestle with that, and to sit with that and to see that complexity as a personification of the complexity and distant cognitive dissonance of this country — a country that has provided millions and millions of people across generations opportunities that they could have never imagined for upward mobility and wealth, and has done so at the direct expense of millions and millions of other people — and that both of those things are American, that both of those things are this country in the same way that all of those different things are Jefferson. So, I think we have to recognize these attacks for what they are, and to not be . . . . They are attempting to instill a culture of fear in people who they hope will be scared and thus push back against it, also in the teachers who are working to teach a more honest history to their students, and it won’t work. Kaler-Jones: I appreciate that call to action and how powerful — as educators, as community organizers, as loved ones and family members, and librarians, and young people — how powerful it is to be the truth tellers and to pass the word down. We’re actually inviting teachers to pledge to teach the truth. In fact, a growing number of states, of course, with GOP bills to prohibit teaching history, and pushing back against that. The link is in the chat box, and the pledges today are really inspiring. So, we definitely ask folks to check it out and add their signature. We also have a campaign on Teaching Reconstruction, one of the most important yet least taught eras in United States history. We would love to hear your favorite encounter with Reconstruction, from your research or new insights that you had while working on the book. Smith: I mean, it’s sort of a macro phenomenon. But, I think one that’s important for students is even the language. I was always taught that Reconstruction failed, and implicit within that is a message that was propagated from the film Birth of a Nation, which depicts formerly enslaved Black people in government as being lazy, just engaging in all of the tropes and stereotypes of Black people in the 19th century, in order to suggest that the reason Reconstruction did not succeed was because Black people were incapable of governance, they were incapable of being part of the political infrastructure. They were lazy, they were dumb, they were unmotivated. So, even if somebody doesn’t say it as explicitly as that, when you say something failed and don’t use it in the passive voice, it suggests a failure of people; rather than using the active voice and saying that Reconstruction was actually violently overthrown. It was violently overthrown state by state after the end of the Civil War by people who recognized what Black people in states throughout the south were doing — gaining political freedom. I mean, you see the numbers of people who were registered to vote in states like Mississippi and South Carolina, the amount of Black people who were in the state legislature of South Carolina in the years following slavery, and it becomes very clear that white people were deeply fearful of the idea that these people who they had enslaved only so many years before were now in some of these places representing the greater population and were thus able to put more representatives into office and thus create policies that would lift those communities up. And there was a recognition that that was unacceptable. With the emergence of the 19th century iteration of the klan, led by Nathan Bedford Forrest, the former Confederate General who is notorious for the battle at Fort Pillow during the Civil War in which he slaughtered hundreds of Black soldiers who were attempting to surrender. Through the klan, through the informal infrastructure of night riders and people who engaged in white domestic terrorism in towns throughout the south, we have these numbers in the thousands. I think over four thousand people were lynched during those years after [the Reconstruction]. But those are just the numbers we know, those are just the names that we know. Even just that simple act of framing it as something that was violently overthrown, something that was taken, something that was destroyed, rather than something that failed, because, again — whether it’s implicit or implicitly suggested or explicitly stated — because of Black people’s inability to self-govern. I think that’s one of the most important things we can do in beginning these lessons. Then, also, one other thing, I learned it from the Color of Money by Mehrsa Baradaran. Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap, excellent book, highly recommended. There’s a line in here that I remember reading that just struck me so much. It’d be very cool if I flip to the page and automatically had it. But, in essence, it is the Freedmen’s Bank, which was created right after Emancipation and was part of the larger infrastructure. The Freedmen’s Bureau was created and Black people were told to put their money in this bank. Whatever meager savings Black people had, put this money in the bank and it will gain interest and accrue and you will have more money that you can transfer to you and you can take it out later. You have more money, you can transfer it to your descendants, to your children, your grandchildren. So tens of thousands of Black people put their money in this bank, and by 1874, less than a decade after, the bank had collapsed and half of the wealth of Black people in the United States in 1874 disappeared overnight. Half of the wealth of the Black people in this country disappeared overnight because of the failure of the people running this bank and the speculative way that they invested the money, and the irresponsible way the money was invested. That’s not even central to the story here. But do you think about half of Black wealth disappearing overnight in 1874, from people who had little to no money to begin with, when we think about what we know very clearly about how intergenerational wealth accumulates is that you have to have wealth to build wealth. If the wealth of people who were enslaved just nine years ago was erased, and half the Black wealth in that country was gone, I mean, I guess that’s my factoid. That was so shocking to me. I never learned that, and it was, again, reflective of what has been done to Black people in myriad ways. We know the big things, we know slavery, and we know redlining, but there’s so many small things like that, right? There’s so many small things across generations that had huge, enormous implications for the wealth that Black people would be able to create. Also, just teaching that Reconstruction, as with slavery, wasn’t that long ago. My grandfather’s grandfather was enslaved. The woman who opened the museum with the Obama family in 2015, who opened the National Museum of African American History and Culture, who rang the bell to signal the opening, her father was an enslaved person. The last Civil War widow died just, I think, last year. This history was not a long time ago. If there is a central operating feature to my historical writing, that’s it. None of this was that long ago. The idea that it would have nothing to do with what the contemporary landscape of inequality looks like is intellectually and morally disingenuous. Kaler-Jones: Yeah, especially in the epilogue when you interview your grandparents, and your grandmother says, “I lived it, I lived it, I lived it,” just bringing us back to the ties between history and today. I want to just highlight, as I move into the next question, how you’re talking about passive voice and active voice and the power of language to construct public discourse, which leads to either the perpetuation of or the dismantling of the status quo and oppression. In thinking about language, the topic of last month’s online class was the prison industrial complex and two of our guests responded with pre-recorded responses since they are incarcerated. Jesse Hagopian, one of my colleagues, asked abolitionist and organizer Stevie Wilson, “What should teachers and students know about prisons and the people inside them?” Wilson began his answer, “I want teachers and students to know that there are people, human beings, in prison.” You not only wrote about incarceration in your book, in the very chilling chapter on Angola, but you also work with incarcerated youth. So, from your visit to Angola and your work with incarcerated youth, can you talk a little bit about why Stevie Wilson really felt the need to emphasize that we should all know that there are people in prison, really highlighting the humanity and how that’s tied in deeply with language? Smith: Yeah, it’s deeply essential. I mean, part of the social function and political function of prison is to render people abstractions, to make us forget them. It is to make us forget that they are for three dimensional complex human beings who are sons and brothers and mothers and sisters and daughters, and people who are loved and who have loved and who do love others. For me, I’ve been working in carceral settings for the last seven years or so. I started my first year of graduate school, in part, because I felt what was happening to me was that I was sitting around in the library reading Foucault all day. Shout out to Discipline and Punish. Theory is helpful in helping make sense of what exists, but if you only exist and only operate in the realm of theory and don’t . . . I can only speak for myself, but I very quickly can lose touch with the stakes, the human stakes, of what is happening — that there are millions, tens of millions, of people entrapped in this cycle that moves them in and out of the carceral system. I mean, we use the number 2.3 million people in prison all the time, [but] it’s closer to 2 million now. Two point three million people in prison and jail. But I think a more accurate number that I wish we used is that there are 11 million people who move in and out of jail every year. Those numbers might be lower now. I’d be interested to see what they are at the end of this year, given the pandemic and given the efforts, at least early in the pandemic, to remove people from jail who didn’t need to be there — because, as a reminder, 70 percent of people in prison, 60 to 70 percent depending on where you are, have not been charged with any crime. They’re there for pretrial detention context. So, for me, teaching in prison reminds me that these are people, and they are people who oftentimes have made poor decisions, and sometimes people who have committed real harm against other people. It is not to absolve people of what they have done. But part of why I think the work that you all do as history educators, as historians, as librarians, as people committed to teaching a fuller and more honest history, is that. I think all the time about this moment. I was having a conversation with one of my students at the D.C. jail about Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law, and he had read The Color of Law, and he was like, “Why didn’t anybody ever teach me this?” Because what was happening was that he was seeing what Richard Rothstein was writing about was how his community came to look the way that it does today. When he’s writing about housing segregation and how the history of housing segregation came to manifest itself in the 20th century, that young man is getting a deeper sense of an understanding about why his community has come to look the way that it does. And what happens with that is that you then recognize that you are not singularly responsible for what has happened to you. Again, it is not to absolve someone of what they’ve done, and it’s not to say people don’t have agency. It’s not to say that people don’t have free will. But it is to say that we have to contextualize the decisions that people make and the social and political and historical context in which they are living and operating. The decisions that one young 17 year old can make, and the decision that another 17 year old can make who was given all of the safety, the feeling of safety, the feeling of resources. I mean, we don’t have two hours, but people forget that these kids are scared. If you grow up in a community that is saturated with violence and saturated with poverty, so many of the decisions that you make are animated by fear. You are scared of what will happen to you and your body every single day. So you can’t talk about gangs without talking about the reason that young men tend to join gangs, being primarily associated with trying to find a community of people who will protect them — who will protect them, who will affirm them, who will make them feel safer than they would by themselves. And I think that that is intrinsically linked to the reason that so many people get tied up in the carceral system, because it begins with them making decisions that are grounded in fear, and grounded in desperation. How different might it all look if we provided people with the social infrastructure of housing and health care and jobs that pay a living wage? Even now, people are like, “Why are people going back to work?” And it’s like, who wants to go back to work for $2.13 plus tips, right? Who wants to go back to work for $7.50 an hour? I think that we have to create . . . and that’s when people are talking about prison abolition, it’s not only destroying or getting rid of prisons, what it is is actually a project that is meant to build and create the infrastructure that makes it so that prisons and the carceral state becomes increasingly obsolete, in the words of the great scholar Angela Davis. You create the world that makes it so that we don’t need prisons to the extent that we do, and we keep moving and building toward that world. Those words are important because the people in prison are people and they’re people, nine times out of ten, who have been born into circumstances that many, many Americans, but for the arbitrary nature of birth and circumstance . . . I would very easily be behind bars instead of talking to you all on Zoom, but I was born into a family and into a set of circumstances where I felt safe, where I was given opportunities and resources that put my life on a different trajectory. But it’s not because there’s something inherently good or talented about me. It’s because I was born into a set of circumstances that allow for my life to be on a certain trajectory, whereas so many of the young men that I work with are born in a set of circumstances that would put most people on a trajectory that entangled them in the carceral system. Kaler-Jones: As we move into our final couple of questions for the evening, one of the things that I wanted to ask you, because I saw your tweet about the number of pages and words that didn’t actually make it into the book, and so what are the stories that didn’t make it into the book? What was the hardest story to cut? Smith: There were a lot of words, tens of thousands of words, that did not make it into the book. One of the hardest to cut was a part of the Whitney Plantation chapter that had a sort of break in it, because part of what’s fascinating about the Whitney — for those who aren’t familiar with the plantation, it’s the only plantation in Louisiana that it exclusively centers the lives of enslaved people in it’s sort of curatorial experience, and it’s one of the only ones in the country, honestly, that does it — it is surrounded by a larger constellation of plantations where people hold weddings and use the the slave cabins as bridal suites and take pictures and selfies in front of the home of enslavers. Part of why the work of the Whitney is so important is because it exists as a fundamental rejection of the idea that a plantation museum should be anything other than a memorial to a torture site. It was a site of intergenerational chattel slavery and torture, and a plantation museum should recognize that and lift up the humanity of the enslaved people who were there. So, part of what I wanted to do in that chapter was talk about the way that, growing up in Louisiana, I experienced plantations. I had this extended section on the first time I went to a plantation. I can remember it was an interview with my mom, who was a chaperone on the field trip, and it was a conversation with her about what it meant to go to this plantation. And for her to try to navigate not wanting to be the trope of the angry Black woman or the disrespectful Black woman, but also having this woman talk about this plantation and not at all discuss slavery, to talk about them as servants, to talk about them as being well taken care of. It is the delicate balancing act that so many Black people, especially Black women, have to navigate in terms of wanting to correct the record, but also fearing that you will be stereotyped and put into the box of the disrespectful, angry, disgruntled Black woman, which then prevents people from actually speaking their truth. And so she was thinking about that. I also went to another plantation in Louisiana, in Baton Rouge, that does kind of the opposite of the Whitney. Also, it’s a place where people have weddings. I’m kind of just meditating on what does it mean for somebody to want to celebrate one of the happiest days of their lives on this piece of land that I can understand as being nothing but a sight of, again, torture for my ancestors? What is it that brings people to experience the same piece of land in fundamentally different ways? How does that happen? So I liked it a lot. Then we had to cut it just because the Whitney Plantation chapter was getting too long. It was a part that wasn’t actually about the Whitney, it was like 5,000 words about this other place, and my editor was like, “This is great. But this is not working in the way that it works.” But, I will say BuzzFeed is going to publish a part of that right after the book is published, they’re going to publish this piece on the phenomenon of plantation weddings. I interviewed a bunch of wedding planners, specifically Black wedding planners in the south, thinking about how people wanting this sort of misguided nostalgia and wanting that to be a part of their experience, their romantic marriage experience. What leads to that? How do you, as a person who’s trying to make money in the south as a wedding planner, do you do it? Do you not do it? Do you need to make money? Do you do it with conditions? Do you? So, again, I think it was all Black women, with the exception of maybe one. It’s like, well, how do you make these decisions? How do you decide, too, because you can make the sort of moral decision of not doing it, that also means that you’re going to lose money, right? You can try to have conversations with your potential clientele about, like, maybe you don’t want to get married to that place; let’s look at this place, and then they go work with somebody else because they think that you’re trying to be too pushy, or, again, thinking about the ways that the fear of being labeled and made into a trope animates the decisions that people make and don’t make all the time. So yeah, that’s the part of the book that I missed. I want to get to the other questions, because we have a limited time. But yeah, that’s one that I wish had been able to stay in the book. But, it’ll be in Buzzfeed. So look out for that. Kaler-Jones: I’m so glad to hear that. I even see in the chat box too, so many words of affirmation, of saying “give us all the words.” Yes, we will. We’re excited to receive them. So thank you. As we think about the theme of this series being Teach the Black Freedom Struggle, can you highlight for us some of the stories in the book that shed light on how enslaved Africans resisted enslavement? Thinking about the theme of the book and places that we remember and places that get forgotten, parts of history that we remember, parts of history that we forget. How do we continue to tap into that ancestral knowledge of resistance, in thinking about your book, the places that shed light on how enslaved Africans resisted enslavement? Smith: Part of what I tried to do, and I do this a little bit in the Whitney [chapter], is to problematize the conception of rebellion and problematize and complicate the very idea of resistance. Because we are taught often . . . part of what I write about is how growing up the only enslaved people I feel like I really learned about were Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, and maybe, if you’re lucky, Harry Jacobs and the characters in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novels. The thing about that is that you are taught about all of these folks who ran away and who escaped to freedom, or who, in the case of Douglass, fought their enslaver and physically overwhelmed him to the point where the enslaver coward away and never beat him again. These stories are deeply important. I’ve read every word Frederick Douglass has written. My favorite biography about Douglass is by David Blight, it’s just stunning, probably the best biography I’ve ever read — just a tour de force, incredible, worthy of every award that it won. I think he won the Pulitzer in 2018 or 2019. The problem is that if you only ever study Douglass and Tubman and Jacobs then you are getting a deeply skewed sense of who enslaved people were. Because there were millions of enslaved people, the vast, vast majority of whom never escaped to freedom, who never had physical altercations with their enslavers, but who resisted in ways that look different but are no less important, are no less valuable, no less consequential. It could be as simple as the resistance people have when they slow down the speed at which they worked, because that had real economic implications for the enslavers. Like, if you work slower, you are taking money from that person. The ways that they would . . . even pretending to be sick, anything that slowed down the economic and financial infrastructure in place that relied on their incessant labor. Then, also, sometimes like when people say, “I think sometimes joy is a form of resistance,” I think it is legitimate. Anything can become overwrought to the point that it is misused. One of the things that I love, I spent a lot of time, I wrote a big Atlantic piece about this a few months ago, was the Federal Writers’ Project narratives, which, if people aren’t familiar, was the New Deal project between 1936 and 1938, where over 2,300 narratives of formerly enslaved people who had largely been children during slavery and emancipation, where they were interviewed in the late 1930s and talked about their experience with enslavement. It’s this really valuable treasure trove of information, not without its issues and limitations, but every primary source document around slavery has its own limitations. But one of the things that I love most about it is that it just captures the simple acts of — I would classify it as resistance — just Black people being people, people reminiscing about how on Saturdays, after the workday was done, people got together in the barn and danced all night. The way that two people who were falling in love would sneak away from the field and find a small tree to hide behind or bushes to sit behind where they could hold one another’s hand and kiss one another, out of the sight of the overseer. Or the way that enslaved children would make fishing poles out of sticks and skip rocks, out of sight of those who attempted to make decisions about what their bodies should or shouldn’t be doing. All of those small things, all of those moments of people being fully human, of being full three dimensional individuals, not simply chattel; rejecting the idea that they were just chattel, rejecting the idea that they were just property, rejecting the idea that they were just something that was meant to be owned and used, and leaning into their personhood, even when it had potentially huge implications. And that’s the thing: it is resistance, because every action that an enslaved person did that moved beyond what their enslavers wanted them to do was punishable and potentially fatal. So, I think making sure that we tell the sort of quotidian, everyday stories of enslaved people pushing back against this system in ways big and small is important. It’s important to teach about the major slave rebellions. It’s important to teach about people falling in love. It’s important to teach about kids playing with marbles. It’s important to teach about people just being people and having families and trying to make a life for themselves in the context of circumstances that just are unfathomable for so many of us to even imagine. Kaler-Jones: Yes, and as you talk about everyday people and everyday stories, I’ll move us into our final question of the evening. In the epilogue, you write, “My grandparents’ stories are my inheritance. Each one is an heirloom. I carry each one as a monument to an era that still courses through my grandfather’s veins. Each story is a memorial that still sits in my grandmother’s bones.” As we think about everyday people and the everyday history that’s all around us, can you talk more about the different ways that we can learn history that are often not lifted up in textbooks, but are rather all around us and that live within our own lineage? Smith: There are so many ways, and one of the things that I wanted to do in this book was lift up the story of the public historians who are doing remarkable, remarkable work. The people who are not academically trained necessarily, don’t have PhDs from fancy universities, but they are people who know as much if not more about this history than anyone. I think that their knowledge is so crucial. Because one hundred thousand people before the pandemic, one hundred thousand people a year were going to the Whitney. I mean, the best selling book about slavery isn’t read by a hundred thousand people, so they are encountering more people than most of these academic texts that are, again, deeply important. It’s not to say that these texts don’t matter, because in many ways the public historians rely on the work that these academic historians who are spending time in the archives are doing. When I go to Monticello and speak with Niya Bates, for example, who was until recently the public historian at Monticello, her desk is full of the books that cover the historiography of slavery. So she needs the Leslie Harris’s, she needs the Annette Gordon-Reed’s, she needs the Daina Ramey Berry’s, and the David Blight’s. And they also need her — it’s a relationship in which each person is building off of the work that the other is doing. So I want to lift up the stories of public historians doing this incredible work at these sites across the country. And also, as I write in the last chapter, I’ve kind of just become obsessed with oral histories. I think just to the extent that people can interview their elders, I mean, it’s such a good project for students. I mean, it took me 32 years to do it, but when I sat down and interviewed my grandparents, I just learned so much, because you’re with your family and you’re with your parents or your grandparents, and if you’re like me you see them at Thanksgiving and you’re with your kids and it’s like, “I love you,” and you give them a kiss. You’re eating dinner and you’re trying to get your two year old not to throw macaroni at her brother’s face, and so you can’t say, “Tell me about what it was like growing up in 1930 Jim Crow Mississippi.” You could, but your four year old would start singing “Everybody Dance Now” and be like, “Why can’t we have a dance party?” So, you’ve got to be intentional about it and you’ve got to be thoughtful about it. Interviewing them was a huge blessing and I’m so glad I did it. I need to do more of it, honestly. But I am very grateful, and I think that if you can get students to ask their elders, if they’re around, parents, grandparents, to have them interview them, and just be intentional about asking them questions about what the world they grew up in looked like provides an invaluable perspective, I think, for our students and for us. What I write in the book is that it took me a while to realize that sometimes the best primary sources are right next to you, and that you don’t have to go into the archives, you don’t have to read a 900 page book. Sometimes you just have to look to your left, or call grandma or call grandpa, call your mom, call your dad. So I think that’s one of the most important things we can do. Kaler-Jones: Thank you so, so much. The power and the beauty and the brilliance of leaning into the sources that are all around us, that live with us, that live in our communities, the stories of everyday people and everyday courage and the everyday resistance that doesn’t make it into the textbooks. You have highlighted that by traveling to geopolitical spaces and sharing the stories of how the word is passed, and how enslavement is remembered in some places and forgotten, the true full history is forgotten in other places. Continue to resist, continue to teach the truth, because we are truth tellers and we have the responsibility of passing the word and passing a fuller, deeper, more nuanced, accurate depiction of history. Smith: Thank you all so much. Kaler-Jones: Thank you so much. We appreciate you. While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Transcript

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Additional Resources

Here are many of the resources recommended by the presenters and also by participants.

Participant Reflections

Here are some of the responses by participants from the session evaluation.

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

Students can deal with multiple complicated ideas at one time.

What Clint Smith said about history not being “political and ideological,” but rather “holistic and honest.”

“Give students the full complexity of a person to wrestle with” and also the importance of teaching about Reconstruction (I NEED TO LEARN MORE ABOUT IT MYSELF!!!) and also all the extra resources shared in the chat.

To teach the history of “fill in the blank” (Reconstruction, Jim Crow segregation, housing policies that elevate white people’s wealth, etc.) is not an ideological endeavor. It’s a way to repair.

I really appreciated learning about the Freedmen’s Bank and the significance of using the active voice when discussing the legacy of Reconstruction.

There is more to history that effected Black generational wealth besides redlining. Our state standards need to be updated to include requirements for teaching the history of racism in U.S.

The most important thing I learned today is to always tell the true story to my students. I also learned that I need to take time to research beyond what is given to me.

It was very powerful and helpful to be reminded that we are teaching a more truthful version of history by talking about race, racism, and slavery.

Teaching the history of human enslavement as the road, not the bump in the road.

I think I’m just inspired to read more, to deep more deeply, to continue pushing myself as a learner to uncover the histories in my community and world.

That the children need to know that it’s the social system that is sick, not them!

The role of memory, and the tension between ideology and empirical evidence.

In the chat, someone mentioned there were a plethora of free Black communities in New Jersey since the time of the American Revolution. I teach and live in NJ and did not know this.

The discussion concerning how our physical landscape of memorials alters historical narratives.

The Freedom Bank story — amazing and so revealing of the way Black (and other POC) are taken advantage, related to way we can easily feel we are the reason for our victimization… which then lessens our resistance to that victimization. Yes!

Most of us educators are passing along a skewed history of the Black struggle, even to our Black children.

The loss of Black wealth from failure of Freedman’s Bank.

How to fill the gaps that we do not know we have. I have heard of the Freedman’s Bank, but did not know that it collapsed, losing half of the wealth of Blacks over night.

From Clint Smith, valuable stories that highlight the complexity not only of slavery, but also of the process folks are going through today as they are confronted with, and struggle with that truth about the United States of America. From my peers? Valuable resources I cannot wait to get my hands on and a recharge for my teaching batteries that have been drained this year like no other year before. From Cierra Kaler-Jones? Brilliant and insightful questions that make me even more eager to read Smith’s book.

The everyday nature of the resistance of the many enslaved Africans whom we never learn about, who are not celebrated in history books but who confirmed their humanity despite the oppression. I was particularly moved by the example of those even who worked more slowly and in this act alone, had an impact on the economy. Also the image of those who would find a way and a private place to express feelings of love to and for each other. These acts of resistance are often overlooked even as we confront oppressive forces today.

Smith’s entire perspective of slavery, jail, and gang affiliation was given. I appreciate the thoroughness of his explanation about why kids join gangs, and the feelings that Black people have in America about seeing streets and schools named after men that have torn up Black lives and communities.

What will you do with what you learned?

With students and colleagues, talk more about what history is and how teaching about racism is NOT taking away anything but telling the fuller story.

I’m drawn to the idea to have the fact sheets about what the monuments in the book represent, have students design a monument, and then have them actually learn about the monuments in the book and read excerpts from the chapter about how people respond to the monuments.

I am going to rewrite some of my teaching materials focusing on changing from passive to active voice.

Looking at redesigning curriculum to allow more time and space to accurately and adequately teach Reconstruction instead of leaving it to a rush at the end of the year.

I have a few new ideas about lessons/activities with students-possibly incorporating interviews into my course as well as thinking about how I might highlight racial history in Nebraska (where I live and work) as a “tour” — something that came up in my breakout room.

I am currently writing curriculum for US history for 8th graders from the lead up to the Revolution through the Civil War. I will be including NJ’s free Black communities and their history in the curriculum.

Encourage teachers to teach place-based history and to use oral histories with students. Encourage teachers to include stories of resistance in ways both big and small.

As a college student studying to become a high school history teacher, I will take what I learned and discover ways to incorporate this knowledge in my college education classes.

I am creating a lesson plan that entails local history. I will have students look up monuments, names of streets and buildings, and schools to research the people and events behind the names. I want to have them create a virtual tour of our city that can be shared with their classmates and families.

Gonna be teaching using some of Clint’s poetry and other writing next week! We’re finishing a unit on slavery, the Civil War and Reconstruction with a project in which students design a monument honoring a person, event, etc of this time, so Clint’s work is so so helpful in framing for students the relevance of this project.

What did you think of the format?

Everything! I loved the time in breakout groups and the chance to come back and hear more from Clint!

Loved and needed breakout group — when you have such a coherent and clear and deep-thinking speaker, I am salivating over the poetic expression of these ideas (as ugly as the historical events are) — But Clint Smith is so authentic — THANK YOU!

Yeah! Deaf-friendly breakout room #1!

I loved the combination of Smith answering questions and then the break out rooms. The resources/ideas mentioned in the chat were phenomenal.

I really appreciate this format. I’m a historian which perhaps doesn’t always add “new” information, but it is helpful to focus on issues or be around those who study in areas that I also do. I typically don’t end up in the most engaging breakout rooms. But I have been able to listen to others’ first encounter with these topics, which is helpful.

I loved listening to Clint speak and Dr. Sierra Kaler-Jones asked such remarkable questions and hosted so well. It was such a treat to push my own thinking and vocabulary and deepened my understanding in so many ways. I wish we had more time to process, because I need to process such big ideas and changes.

I really enjoyed the breakout room sessions as a chance to debrief with others, and I appreciated that there was a facilitator to help guide conversation. This was honestly such a smooth and well put together seminar. Thank you for all the thought and energy you put into hosting it!

I could have listened to Clint Smith talk for hours, but I really enjoyed engaging with people from around the country to discuss and reflect. And then it was great to get back to more Clint!

The breakout group was really productive today. It felt like a space teachers were sharing pedagogically

Additional Comments

Thank you for all you do to make these sessions happen. They always are life-giving for me and help me to feel hope about our country and what it could be.

I would like a letter to write to my school board for the case of Africans in American history. If the letter — to the board — can make a case for the purpose of African history in America does not mean excluding others history. That the history of Africans are vital to the foundation of American history.

This was such a powerful presentation and more importantly, Dr. Clint Smith reinforced the importance of educators engaging in culturally responsive teaching and commit to being “myth busters” in regards to teaching U.S. history.

I so look forward to this learning community. I am no longer in a formal classroom teaching. And I teach lots outside. It’s so great so that I can hear what’s up in the world of formal published ideas by some of our great thinkers and teachers.

I loved ‘the landscape of inequality,” a great metaphor for understanding what happened. The flip side of the myth of meritocracy is the myth of blaming individuals for their own circumstances. I had never had heard of Whitney Plantation.

I loved being in a space full of educators, it’s so so powerful to see people who want to do the work you do.

Thank you for providing the ASL interpreters.

Thank you, thank you, thank you this series continues to inspire me, gives me events to look forward to and so much amazing follow up material. Not only is the content making me a better history teacher, but the invigoration of being able to talk with other passionate educators helps me keep bringing my A-game to class every day during this unprecedented year.

Miigwetch Zinn Education Project!

I so appreciate ZEP and other organizations, speakers, and authors who push me to new heights!

The format and content of each session I have attended leave me full of admiration for the work of Teaching for Change. This course confirms for me that there can be no serous anti-racist work without a people’s historical approach. Without history, the work is short-lived. With history we know we are in for the long haul! Keep up the good work, Teaching for change and Rethinking Schools!

Presenters

Clint Smith‘s essays, poems, and scholarly writing have been published in The Atlantic, The New Yorker, The New Republic, The Paris Review, the Harvard Educational Review and elsewhere. His 2016 book Counting Descent, won the 2017 Literary Award for Best Poetry Book from the Black Caucus of the American Library Association, was a finalist for an NAACP Image Award, and was selected as the 2017 ‘One Book One New Orleans’ book selection. Smith is a teacher, and he previously taught English in Prince George’s County, Maryland and currently teaches writing and literature in the D.C. Central Detention Facility.

Cierra Kaler-Jones is a staff member at Education Anew and a Zinn Education Project team member. Her research focuses on how Black girls use arts-based practices (such as movement and music) as forms of expression, resistance, and identity development.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn