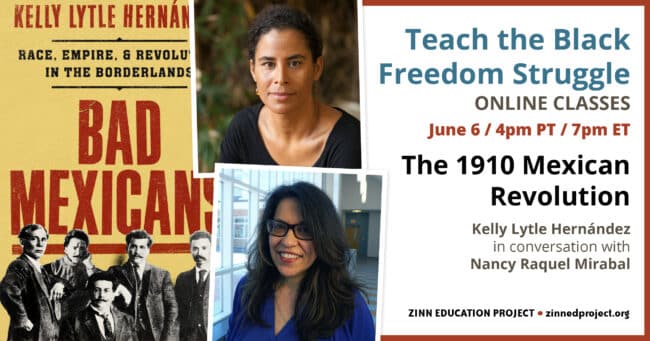

On June 6, the Zinn Education Project hosted author Kelly Lytle Hernández in conversation with historian Nancy Raquel Mirabal to talk about the magonistas, a group of insurgents who challenged Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz and U.S. imperialism in the early 20th century.

Followers of Mexican anarchist and activist Ricardo Flores Magón, the magonistas and their revolutionary actions play a significant part not only in the Mexican Revolution, but also in the creation of the present-day U.S. police state and corresponding immigration and incarceration policies. Lytle Hernández and Mirabal held a lively conversation connecting these daring Mexican rebels to the labor struggle and the Black Freedom Struggle in the United States.

Event Recording

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: On behalf of the Zinn Education Project, we would like to welcome everybody to our class this evening with Kelly Lytle Hernández on the 1910 Mexican Revolution. Some of you are joining us for the first time, welcome, and some of you have participated since we launched this series and have been to many, many sessions with us. It really is a gift to be able to share this time together, and I want to thank you for being in virtual community with us — especially right now, especially after this long, hard school year. I think it’s especially important for us to come together right now and support each other in a time when we are dealing with the collective trauma of the white supremacist massacre in Buffalo and the school shooting in Uvalde, Texas.

I think in times like this, we really have to practice hope. As the great abolitionist author and organizer Miriame Kaba reminds us, she said, “Hope doesn’t preclude feeling sadness, or frustration, or anger, or any other emotion that makes total sense. Hope is a discipline. And we have to practice it every single day.” And I feel like this course helps us practice that discipline of hope, month after month, through so many injustices that we have endured. But being with you all, and hearing about how you are persevering — pushing back on these anti-history laws, and teaching your kids the truth — is so uplifting for me. It’s helped propel this movement forward. We are really excited about the fact that the teach truth movement is hosting its second annual weekend of action, June 11 and 12. All across the country, in dozens of cities from Alaska to Florida, educators are going to be taking to the streets, holding rallies at sites in their community that reveal something about the Black Freedom Struggle, about struggles against oppression and sexism and homophobia and racism, and sites that we couldn’t even talk about if these bills pass. So I’m looking forward to seeing you all in the streets.

I wanted to let everybody know that today’s course is hosted by the Zinn Education Project, which is coordinated by Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change as part of our Teaching for Black Lives Campaign. We offer free downloadable people’s history lessons that I hope many of you have already used. If you’re new to the Zinn Education Project, you should check that website out for sure. We have all these lesson plans to help challenge master narratives and introduce counternarratives for middle school and high school classrooms. And we are also very fortunate this evening to have with us ASL interpretation — we greatly appreciate you being here this evening, Krystal Butler and Tyriibah Royal.

Before we begin our conversation, we want to find out who’s in the room and go through our plans for this evening together. So we’re going to post a quick poll to find out how many teachers are in the house, how many librarians, teacher educators, historians, parents, students, educators of all kinds are with us. And many of you have multiple roles, so just pick one of your primary roles.

All right. Yes, the numbers are coming in. I’ll let folks know who’s in the house with us very shortly. But, we also have members from our Teaching for Black Lives study groups with us this evening. If you’re in one of those study groups, please add T4BL after your name. We appreciate that. Also, throughout the session we want you to use the chat box to post questions and comments and resources and ideas, and we’ll do a short evaluation at the end. In about a week we will share the full list of the recording of this session and also all of the resources that were shared in the chat box. We also want to encourage you to tweet about what you are learning during this session today. Then, after about 25 minutes of this conversation, we’ll pause so that you can meet each other, talk in small groups, and share your thoughts with one another. Then everyone will come back and you will get to hear from Dr. Hernández again and have any questions answered from your small groups.

Before I welcome our host today, I want to just reveal who’s with us today. We have 41% of us are K–12 teachers; we have 1% students with us; 5% family members to a student; we’ve got 16% teacher educators; we have 9% historians; and 1% librarians. So, welcome everybody, so glad to have you with us. Now I would like to welcome Nancy Raquel Mirabal, a board member of Teaching for Change, one of the two groups that’s coordinating the Zinn Education Project. Nancy is going to conduct the interview with Kelly Lytle Hernández today, the author of Bad Mexicans: Race, Empire, and Revolution in the Borderlands. I’m so excited for this conversation.

Nancy Raquel Mirabal: Well, welcome everyone. This is such a treat. I am so honored to be here to conduct the interview. First of all, Dr. Lytle Hernández, I want to congratulate you on your book, Bad Mexicans: Race, Empire and Revolution in the Borderlands. It is truly beautifully written, and you did such a brilliant job of fleshing out the different historical figures and providing us such an intimate reading of events. It really felt like you were right there in the rooms, reading the newspapers, just having these intimate conversations.

You also detail the hardships and the toll political organizing and revolution took on the activists and their families, and it’s just so well done. As I was reading your book, I was reminded of why the Mexican Revolution is so important to not only Mexican history, but also the history of the United States. So, for my first question: the Mexican Revolution begins in 1910 and it ends around 1917, but your book focuses on the period before the revolution. So my first question is, why did you choose to focus on the period before the revolution?

Kelly Lytle Hernández: Sure, and that’s a great question. First, let me thank the Zinn Education Project and you, Nancy, and Teaching for Black Lives for the chance to be here in conversation and community with you all.

So, why did I focus on the pre-revolution period, or the storm before the storm, as some say? Well, this book is about a particular group of instigators, of rebels, of insurgents who were active between roughly 1900 and 1910, and their primary role was not to go on and lead the armed struggle, or the political struggle of the formal revolution, but rather to sow the seedbed of insurgency, to open up the radical possibilities. And that group is journalists and miners and cotton pickers and farmworkers who come from Mexico to the United States, as well as a group of Mexican Americans who are led by someone named Ricardo Flores Magón. Led is probably too strong of a word — they are a collective. They’re often known as magonistas. And what’s so important about them is that before the revolution gets into its armed struggle, and before people begin to battle over what can actually be applied immediately, they want to think about the radical possibilities. I think in some ways, we could imagine our abolition movement today as being the ally to their movement in the past — that they want to think beyond what structures are currently in place and what is possible for workers, for the dispossessed, for the historically marginalized and aggrieved, especially racially aggrieved communities — what’s really possible so that we can have full, whole, healthy, vibrant lives.

Mirabal: Wow, yes. It also looks at activism and organizing that takes place in U.S.-Mexico. One of the things that this book does so beautifully, so well, is that it shows that the organizing is taking place in the United States. St. Louis, Missouri, for instance, becomes the center of this kind of organizing. And there’s Texas and Montreal, and all over the U.S. We know that the Partido Liberal Mexicano [PLM] is even founded in St. Louis, Missouri, as you tell us. In the newspaper [illegible], he moves from Mexico to the U.S. and that Ricardo Flores Magón is traveling through most of the United States, giving speeches, and he’s in conversation with other activists. So given the importance of this revolution, and the United States’ role in it, why do you think the Mexican Revolution should be taught more as part of U.S. history, and what can young people learn from the Mexican Revolution?

Lytle Hernández: I think this story about Ricardo Flores Magón and the magonistas and the Mexican Revolution should be a part of the canon of the so-called American or U.S. history story. Why is that? Well, first and foremost, during the Mexican Revolution, 1910 to 1917 roughly, about a million Mexicans migrated to the United States in search of sanctuary, as refugees and as labor migrants. And that mass migration really is the foundation of the birth of the large Mexican American population that we see today.

So, if you want to talk about major moments that transformed who we are as a people here in the United States, the Mexican Revolution is certainly a part of that story. For that reason alone we should be thinking about the Mexican Revolution within the U.S. history canon. In addition to that, why I really liked this particular group of rebels who are active before the revolution gets started, who helped incite it, is they really bring to the table the most radical sets of possibilities and questions that become a little squashed as you move toward developing the constitution and implementing the constitution. But, if you want to think about non-white immigrant roots, and what kind of radical possibilities and thinking and politics that they bring to the United States, the magonistas are at the center of that story. I think that’s really important for us today. A lot of people are talking about the so-called Hispanic Republican, and whether or not this new voting body will be Democratic or Republican. And the magonistas really explode all of that and say, “No, we actually want to be anti-capitalist. In many cases, we want to be anti-racist. And the sense of solutions that are being offered to us by the leading parties aren’t what we’re about. We’re imagining outside of that. We’re working outside of that.” So I think that’s also important — that there’s a legacy here for radical Latinx organizing.

There’s a lot of stories here also. For example, there’s major things that have happened in U.S. history that Mexicans and Mexican Americans have been written out of, and really ignored. Let me give you one example. There are few institutions as significant or as well-known, as iconic as the Federal Bureau of Investigations, the FBI. Typically when we hear the story about the FBI, if you know much about it, maybe it’s [J. Edgar] Hoover was at the beginning of the FBI, or maybe the Red Scare and the efforts to arrest Emma Goldman and others. Well, if you keep peeling back the layers, you go back to the very beginning of the FBI in the summer of 1908, which is when they’re established. They’re established just a couple of days after this group of Mexican rebels, the PLM, launched their most lethal raids against the dictatorship in Mexico. They launch those raids from Texas. Right as the FBI is getting started in the summer of 1908, those raids happen. So the U.S. Department of Justice, and no one less than Teddy Roosevelt, pickets the beginning of the FBI, and they make sure that one of the FBI’s first big cases is hunting down the magonistas and trying to suppress the outbreak of the 1910 Mexican Revolution. So, this is another example of how telling this radical story helps us to understand that Mexico, and Mexican immigrants, and Mexican Americans are really at the center of so many so-called American stories, but we’ve been ignoring it today when we have got to begin expanding our understanding of U.S. history.

Mirabal: There’s so many examples of that throughout the book, and I just thought that that was so brilliant. Now, one of the things that I thought that you did so, so well is that the leader of the PLM, Ricardo Flores Magón, is a very complicated figure, and you capture his nervous energy, his persistence, his really fierce intelligence and almost perfectionism throughout the book. But he’s also a man of his time, right? He’s got some issues and he can be very complicated. So, how did you navigate those contradictions, and why did you think it was important to have this kind of portrait of Magón?

Lytle Hernández: Thank you. So much of the writing that’s been done on Ricardo Flores Magón, not all, but much of it sets him up as an icon, as an unproblematic icon, as someone who was brilliant and daring at a time when nobody else would name the dictatorship, at a time when nobody else would really speak truth to power when it came to the United States government. He was doing all of that, absolutely. But the man who had the brilliance and the courage to really lash out at the dictatorship was also the man who would lash out at his friends and his comrades. So one of the greatest weaknesses of his leadership, I would argue, is that he wasn’t able to build a strong political community around him because of some personality issues. I think it’s really important to give the full story of who we are as movement participants. In this case as a movement leader, he was an imperfect person, but he went on to really challenge the United States government and the Mexican government.

So, I think it’s really important to tell the whole story. I have to also say that this is my quarantine book — I wrote this while we were all in shutdown. But it’s also my uprising book — the uprising for Black life that was unfolding in summer 2020, in particular. As I was writing about Ricardo Flores Magón, I’m quite active in the movement to end mass incarceration, and in many ways I was watching some dynamics play out on the ground that I was seeing in the archive, and I felt like I could understand him a little bit better after 2020 than I had prior to that. I love him in many ways, but also understand the limitations of his leadership. For him in particular, it was around gender and sexuality that he would excise people from the movement if he felt that way. If they didn’t agree with him politically, he would then out people around issues of gender and sexuality. So I just felt like it was really important to tell his full story.

Mirabal: I have to say, I was familiar with Magón, but I felt like I didn’t know him until I read your book. And then I was like, “Oh, this is a much more different reading of Magón.” And I thank you for that, because the portrayals have been sometimes almost lionized, as you mentioned. Toward the end of the book, as we move closer to revolution, I just had to mention this: you begin chapter 25 with a brilliant sentence. I have to say, it’s one of my favorite sentences in the entire book, which is, “Revolutions are hard to schedule.” I think that really brings to light the energy and the chaos, and I really enjoyed that. But it’s the conclusion, Always a Rebel, that I really found moving. You end the book with Ricardo Flores Magón, he’s sick, he’s living in Edendale, on the eastside of Los Angeles — and I’m from Huntington Park, so I know that area well. You see, he has a very powerful statement, which is we have all paid a price for overlooking Latino history. And I wanted to know why, at that chapter, with his story, that you then talk about what it is that we’re missing in not including the history of the Latino community and in the U.S.?

Lytle Hernández: Well, I think this is why I’m so excited to talk to this group, in particular, is because this book is a smuggling operation, really — and I hope you all join me in this smuggling operation. What I’ve done is tried to tell a story that is really riveting, it’s got tyrants and spies and deportations and assassins and all that. It’s got all the components of a riveting, cinematic tale. But within it, you can smuggle in key moments in Mexican American history. When does mass migration begin, and more importantly, why? And the answer is U.S. imperialism in Mexico.

I can smuggle in the early history of this new form of racial inequity that’s developing in the United States following the U.S. Mexico War, and that is called Juan Crow. What was it that these Mexican migrants confronted when they arrived in the United States? They confronted racial segregation in housing, in education, and in jobs, they confronted racial violence. We talk about the history of anti-Mexican lynchings across the southwest United States: more than 500 Mexicans and Mexican Americans were lynched between the 1870s and the 1920s. That’s a part of the story. In fact, this book about starting a revolution in Mexico begins with a lynching of a Mexican by a white mob in Texas.

And there’s so many more stories. So, what this book is trying to do is give you something, give the general reading audience something dynamic to read. But along the way you’re going to learn a lot about Mexican and Mexican American history, and hopefully say to yourself, for the folks who don’t know these stories, “If I don’t know this about how Mexicans and Mexico and Latin Americans have been central to the American story, what else do I not know? What book do I need to go read next? What young student do I need to support so they can help to tell these new stories?”

So I guess the point of this book, in many ways, is to expand and amplify our understanding of power in the United States and racial inequality in the United States, the ways in which policing and the carceral state have been expansive and elastic to impact non-white immigrant communities. All of that is here. And when we haven’t told Mexican and Mexican American histories we’ve been cut off from understanding, really, a large segment of our population today and their positionality within the United States. So, I think that’s a couple of the reasons why it’s absolutely critical that we broaden the canon of U.S. history to truly include Mexican and Mexican American history. And there’s a lot more work to do on that — the magonistas are just the beginning of that story.

Mirabal: One of the things that I didn’t know that your book highlighted was the efforts by the magonistas to give land back to the African Americans and the Indigenous, and literally to kill white people and to dispossess white people. They had a theory around settler colonialism, and I didn’t know that history, and I had actually studied the Mexican Revolution. I found that to be fascinating. Could you speak a little bit about that particular part of the history? Because it seemed that that was what was most threatening to the U.S. too.

You also do a really beautiful job of showing how U.S. capitalists are really terrified of the revolution, and terrified of what could happen not only in the U.S. but to their investments in Mexico. So there’s this almost conflation between property, whiteness, and the magonistas’ understanding that and acting accordingly.

Lytle Hernández: That’s right. I’m so glad you asked that question. I’m going to take a little bit of a step back to answer that. What happens during the 19th century, we all know, is that the United States government marches across the North American continent laying claim to Indigenous lands in what was then claimed as Mexico in the spirit of Manifest Destiny, creating new lands for white settler citizens, in particular, to occupy. With the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1876, major U.S. industrialists from the railroads to everything else looked out and said, “What’s next?” And they find Mexico and they begin to build the railroads into Mexico, to go down to Mexico to buy up land on the cheap and they begin to stitch together the rise of U.S. imperialism. It really takes its first steps in Mexico. And U.S. imperialism, of course, is a white supremacist form of imperialism. So, even in Mexico, Anglo Americans are imported in to become managers, to have the high wage jobs, and Mexicans and Indigenous folks are really relegated to low wage, dangerous labor that’s often done at the end of a whip, in the sense that the Mexican police — known as federales— are enforcing the will of foreign and domestic investors and employers. It’s the rise of what W. E. B. Du Bois would call “the global color line” that helps to define the U.S.-Mexican relationship in the early 20th century. It’s that challenge to the global color line that the magonistas are bringing. That’s important to note, because as the magonistas are challenging a white supremacist form of U.S. imperialism, African Americans are watching very closely. Gerald Horne is one person, at least, who has done this work to talk about the way in which Black folks are watching what’s happening in Mexico and hoping that Mexican revolutionaries can really snap the spine of the global color line and create possibilities for all of us to find sanctuary in Mexico.

One of the things you see happening throughout the magonista story is that African Americans do pop up from time to time. The archive is thin, but we have to be able to imagine what is going on behind the archive. That when Ricardo Flores Magón is on the run and he’s living as a fugitive, one of the places he comes to is Los Angeles, and he finds a hideout at the edge of town that his life partner Maria finds for him by contacting an African American real estate broker. So, he finds sanctuary within a home provided by a Black real estate broker here in Los Angeles. As the magonistas gear up into the revolution they occupy Baja California in 1911 for several months, and Black folks go down to join the occupation with the idea that if the magonistas, the radical possibilities of revolution, can triumph, can win, what might that mean for Black life, and the possibilities of Black life in Mexico? Now, of course, all of this is built upon a longer history and trajectory of Black freedom-seeking in Mexico that stretches all the way back to the period of enslavement, where, for many of us, it wasn’t a Northern Star, it was a Southern Star — that if we could get to Mexico, that would be the place that we could find a sanctuary. So, there’s a long history between Black folks and Mexico and Mexican rebels that this story of the magonistas is certainly a part of.

Mirabal: One of the questions that I wanted to ask was about the title of the book, why you decided to title the book Bad Mexicans and all the multiple meanings of bad Mexicans with the book.

Lytle Hernández: Okay, great. Thanks for the chance to talk about this. It’s certainly a provocative title. So, this group of Mexican dissidents that I’m talking about, Ricardo Flores Magón and his colleagues, began organizing against the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz in Mexico by starting up a newspaper called Regeneración. On the pages of that newspaper, they would call Porfirio Díaz a dictator and say that he had made Mexicans the so-called servants of foreigners by inviting so many foreign investors into Mexico to buy up land and dominate industries. And for these activities, for challenging his regime, Porfirio Díaz and his regime labeled these rebels malos mexicanos, or bad Mexicans, for not being compliant to the dictatorship.

Once they come to the United States — really flee suppression in Mexico — in 1904, they were able to relaunch their newspaper in Texas. They began in Laredo, then go to San Antonio, and then St. Louis and begin living on the run. They restart their newspaper Regeneración, they establish that political party, the PLM, and they establish this army. And for challenging Porfirio Díaz’s rule in Mexico, but also for agitating among Mexican migrant laborers in the United States. Powerbrokers in the United States — white folks in Texas and elsewhere — thought that Mexicans should be docile and compliant and just be laborers who come and go with the seasons and are quiet and silent within society. By stirring up all this political organizing among Mexican laborers, white folks across the borderlands also disparaged the magonistas as malos mexicanos, or bad Mexicans. Because a good Mexican is a quiet worker, right? A bad Mexican was politically engaged and organized and challenging those regimes and those rules. So that’s why I titled this book Bad Mexicans, because it was a term that was utilized by the United States governments to try to disparage the organizers.

But also, of course, because we recently had a president here in the United States who tried to disparage Mexican migrants as so-called “bad hombres.” So I’m playing with that. That was very dangerous rhetoric, to cast an entire group of people as “bad hombres.” But it’s also stirring up this history of racial violence against Mexicans and Mexican Americans, or non-white immigrants coming from south of the border more specifically. I wanted to call out the danger of that kind of rhetoric that’s even being used today. To do that, I wanted to use this kind of mirrored language that was happening in the early 20th century, as opposed to what’s happening today in the 21st century. Really the reason why I call the book Bad Mexicans is that there’s so many different ways, so many different angles, that this group of politically engaged Mexicanos are being disparaged.

But, in the end, there’s this wonderful speech that one of the rebels gives when he was put on trial in Mexico for leaving the revolution. His name is Juan Sarabia, and the speech is known as his “Menace to Authority” speech, where he is charged with insurrection against the Mexican state. Rather than saying, “Oh, I didn’t do it” or “you got the wrong guy,” he says, “Hell yeah, I did it. Let me tell you why I did it. And you’re going to call me a bad Mexican for doing it, and I own that. Yeah, I’m not compliant.” It’s also a part of claiming the pride of revolution, or claiming the pride of insurrection, and they did that. As magonistas, as rebels, they didn’t ever shy away from the fact that they were challenging the regime, and they never bit their tongues or curbed their words or their politics. They were very confrontational and oppositional.

Hagopian: Thank you for that. We’re also getting some great questions in the chat that we’re going to move to soon. So, thank you for dropping those in the chat and keep them coming. There’s a lot of love coming in the chat, as well. Wendy says, “Thanks room 15.” Tyrone says, “Dr. Hernández lit that fire.” And Keisha said, “Thank you, Nicole, Suzanne, Shane, Laura, and Esther for such a great conversation.” So it sounds like there were some great conversations happening in the breakout rooms. Mark says, “Thanks to Barbara for stepping up.” Then Martha says, “Thanks, Tamara, for your energy and enthusiasm facilitating the room. 18 This is awesome. I think there’s sparked a lot of ideas already for lesson plans that can transform our classrooms.” I just had one question I wanted to come in with before I turn it over to Nancy. In the first session, you talked about Juan Crow and the racial violence against Mexicans and Mexican immigrants. I would love it if you could talk more about the connection between Juan Crow and Jim Crow.

Lytle Hernández: Another great question which is particularly relevant for K through 12 teachers in how do we get this story into the curriculum. So, I always approach U.S. history with the presumption and the knowledge that the United States is a white settler state. And what does that mean? That it’s predicated upon the occupation of Indigenous lands and the theft of African Black labor. That is the baseline of the U.S. story, and of U.S. history. Emerging from that, in post-emancipation as we have an ongoing occupation. As Indigenous scholars and Patrick Wolfe have taught us, invasion is not an event — it’s a structure that continues to this day. The occupation continues to this day.

So, following enslavement with ongoing occupation, we have the rise of something called Jim Crow. I think many folks are very familiar with it. How do you manage and control and extract Black labor? Prevalent, of course, in the U.S. South, but across the United States wherever Black folks are, we have never been imagined as being fully incorporated citizens of this white settler state, but rather as bodies and beings from which labor is extracted — and if not, then temporary. That’s the definition of racism, [which] according to Ruth Wilson Gilmore and others is the preeminent short death [actual quote is “Racism, specifically, is the state-sanctioned or extralegal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death.” From Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California].

When we’re not getting profit extracted from us, we’re on our way toward death or extinction. When you begin U.S. history with that presumption, then it’s easier to understand what happens to non-white immigrants as they begin to arrive in the United States in the late 19th century, whether that be Chinese immigrants or Mexican immigrants. The particular form of racial and social control that targets Mexican immigrants in the U.S.- Mexico borderlands, or those border states where they first have large populations, is an echo of what’s happening across the United States with Black folks, where anti-Blackness is the basis of everything.

From that you have the growth of Juan Crow. It’s not exactly the same. I would say that it’s not as regimented, where you have significant exceptions that are made for white-presenting Mexicans or white Mexicans in particular, and wealthy Mexican Americans — there’s a considerable number of them — that the forms of Juan Crow and its most violent manifestations certainly target brown skinned Indigenous Mexicans who are crossing the border who are being told where they can live and where they can’t live, where they can go to school, where they can’t go to school, what kind of jobs they can have, and who are being targeted for lynching campaigns. So, that’s what I would say is Juan Crow. It’s derivative of the white settler state, as is Jim Crow. It has its own specificity in the borderlands. In particular, I would say that it’s not as singular — with the one one drop rule really impacting all Black folks in a shared way — you don’t have that happening in Juan Crow. With that said, one of the distinctions that’s happening in Juan Crow is the beginning of this new federal system called immigration control that impacts non-white immigrants, Chinese immigrants, Mexican immigrants, and others. It began to take shape in the early 20th century and is a new regime or settler institution that targets non-white immigrants.

Mirabal: We have a question from the chat that we’re going to go ahead and ask. Could you talk about the relationship between the Mexican revolutionaries and the early 20th century labor movements in the southwest, particularly in the mining regions of Arizona and New Mexico?

Lytle Hernández: Thank you for asking that question; it’s a great one. These revolutionaries, the magonistas, organized in border communities across the U.S.-Mexico border, and some of their strongest polings were in southern Arizona, in these mining towns where Mexican migrant laborers would come over and become miners. And the conditions were horrendous. So there’s a very close connection between the labor movement that Mexican Americans are playing a significant role in the minds of southern Arizona, and the rise of the magonistas.

There is an attempted raid that happens from southern Arizona in 1906, where miners are joining the PLM army left and right out of southern Arizona. It ends up getting thwarted by the U.S. Immigration Department and others, but the southern Arizona mines are a hotbed of radical organizing activity. It’s important to note that they’re connecting with the PLM, but they’re also connecting with the Socialist Party in the United States. In time, we’re going to connect with the Wobblies, the I.W.W. Mexicans, Mexican Americans, and a large number of Indigenous Mexicans — as the work of Devra Weber has pointed out — play a significant role in the I.W.W. across the western United States that historians haven’t talked about very much.

So yes, that’s all here, the connections between the two. One of the really interesting things that the magonistas are able to do, they’re able to tell U.S. labor organizers, particularly the Anglo Americans who are trying to figure out why do we care about a revolution in Mexico? Well, they tell them, “Look, if you think that the Guggenheims and the Rockefellers and the Dohenys and all these folks have too much money, ask yourself where they got all that money. They got it out of the United States, but they also got it out of Mexico. When Porfirio Díaz was giving them all this land and all these tax rebates and all that, they’re either making or multiplying their millions in Mexico. So, if you want to take them on, if you want to really cut them off at the knees and really go after their purse that makes it possible for them to hire spies and Pinkertons and whatnot to shut down the labor movement here in the United States, you have to address what’s happening in Mexico.”

And that pivot is really important because a large number of U.S. socialists, Eugene Debs, Mother Jones, and others all get on board with the magonistas movement and see it as critical to strengthening and supporting the U.S. labor movement.

Hagopian: That’s so wonderful. That is history that I feel like I really need to dig into right now, knowing something about the socialist movement at that time, but not knowing the connections to the Mexican struggle. I feel like I have some homework myself, so thank you for that. There’s more great questions in the chat. There were a couple of people that just asked what’s the name of the magonista who gave that moving speech? Then there is a question that says, “From your study, which types of activism were most or least successful in carrying the message of economic and political reform during the revolt against the Díaz?”

Lytle Hernández: Okay, so the first question was “Who was the magonista who gave the ‘menace to authority’ speech,” and his name was Juan Sarabia. Actually, if you read Spanish, his biography is freely available online. It was published quite some time ago. But you can check that out. The title is Juan Sarabia: A Martyr for the Revolution.

Then the second question was “What were the tactics I think were most successful?” I think they were all successful to a certain degree. I’m an all hands on deck kind of organizer, so we need intellectuals, we need fighters, we need teachers, we need everything. So the newspaper that they ran, Regeneración, played a significant role in opening up the world of ideas and helping people to build the political community across space. When the magonistas in Regeneración would say “Look at this incident of sexual violence that happened in this small town in Mexico,” and then they’d spread that story in that newspaper across Mexico, people will start to say, “Well, wait a minute, we had a similar incident of sexual violence here in our community.” Or, “wait a minute, we had a similar experience of sexual violence in our community.” And when I say sexual violence, the importance here is that the Porfirio Díaz regime has this localized system of governance and he would allow the chefes, or the mayors, extraordinary levels of local power. They would tax people to really fill up their coffers, but they also subjected largely women and girls to high levels of sexual violence. It’s when people start to pull these stories together — “It’s not just me, it’s not just my town. This is systemic and endemic.” — that’s how you start to build a revolution, as people share those stories. So that was really important work.

Building the PLM Army was really important work in the sense that when they raided Mexico four times from Texas from 1906 to 1908, and they were able to rattle that cage of the Díaz regime to show people maybe he’s not that powerful after all. You got ordinary people here — miners, cotton pickers, people who have been dispossessed — who were willing to go in and challenge the arms of the dictatorship. That was important. There’s so many other things that people are doing. I think that it’s all significant.

I would say that one shortcoming of Ricardo Flores Magón is that he was a brilliant intellectual, but he found his role to be solely intellectual. While he is encouraging people to go to Mexico to fight, he never returned to Mexico to actually join the fight, or at least even be an intellectual in Mexico as the fighting begins. I think that that was a shortcoming in terms of tactics among leaders, that if you don’t go to the front lines with everybody else . . . well the leadership began, from my perspective, to crumble at that moment.

And with that, I want to say and lift up the name of one other revolutionary who took prominence when Ricardo Flores Magón was incarcerated for three years here in the United States. That was a man named Práxedis Guerrero, and he was an unlikely revolutionary. He was born into extraordinary wealth in Guanajuato, in a hacienda. He went to school with private tutors, taking equestrian lessons, and writing poetry. But as a young man, as a late teenager, he decided he was ready to renounce his family’s wealth and travel to the United States and live as a migrant laborer, as so many other Mexicans were beginning to do. When he was working as a miner — we go back to those Southern Arizona mines, he was working as a miner in southern Arizona — he met up with Manuel Sarabia, a member of the PLM, and he joined the PLM. What’s so important about Práxedis Guerrero is that he had the power of both the pen and the sword — he would write these extraordinary pieces, quips really, that helped people understand what was happening. I’m going to get the phrase not quite right, but “if you can’t get to freedom by walking, then run.” And people would share these clips like wildfire. One of his more famous quotes was, “It’s better to die on your feet than to live on your knees.” Everybody’s heard that phrase from the Mexican Revolution? Práxedis Guerrero helps bring that to Emiliano Zapata and the Mexican Revolution. So, Práxedis Guerrero is a writer, but he’s got the quips that can be used in oral culture, oral traditions that we move. So, books are important, but storytelling is probably more important. And I’ll say that as a writer.

But he also is willing to fight. He goes down into Mexico several times and he leads several of the raids. He’s actually killed in a raid in 1910, in the early phases of the Mexican Revolution. Tactically, my editor always said, “I think you’re in love with Práxedis Guerrero.” And I said, “I think you might be right. I think you’re totally right.” I loved his blend of both writer and fighter, of action and ideas. For me, we can bring all those tactics together, that’s where the power is.

Mirabal: Oh, yes, we fall in love with our subjects, don’t we? What role do you think the U.S. Mexico War played in this, and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo? In many ways, the magonistas are almost fighting against those events that take place. And how the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo gives a third of what we know is the United States — not gives, but takes, seizes — those territories, then the question of land rights and so forth. It just seems that in many ways the Mexican Revolution is still dealing, still reckoning with what had taken place during that time.

Lytle Hernández: Sure. Again, when we talk about the United States being a white settler society, the U.S. Mexico War is certainly a part of that story, and the ongoing occupation of all these lands through war and broken treaties. I would say that not only is Mexico still reckoning with that, but here in the United States we are still reckoning with that. I think one of the areas where we could strengthen some of our social movements, racial justice movements, environmental movements, whatnot, is in bringing to the fore the idea that we are living in the Age of Occupation, we are living in the Age of Conquest. That didn’t happen back then, it is happening right now in front of all of us, around all of us, inside of all of us. I would say it’s not just important for Mexico, it’s important for us to take up these questions of land and occupation, and indigeneity, and how they structure or at least impact questions of racial justice in the United States as well.

Hagopian: Yeah, no doubt. I know after I teach the Mexican American War, I usually show an image from one of the immigrant rights rallies with someone holding a sign that says “The border crossed us, we didn’t cross the border” and asked the kids to discuss the validity of that step, that message. It’s just a lot of hypocrisy to talk about illegals when you look at how illegal that war was to begin with. So thank you for that. Nancy, did you have a question about La Migra!?

Mirabal: Yeah, there’s a great question about women in the movement and the role of Benito Juarez there. So, I want to give some time for that as well. But yes, I don’t know if people know this, but you’ve written other monographs, really award-winning monographs, City of Inmates, Migra!. Can you expand upon your research and your work on immigration with this book that you have just written?

Lytle Hernández: I’m a historian and I work largely on immigration, race, and this thing we know as mass incarceration now, or the carceral state. My first book was this book called Migra!: A History of the U.S. Border Patrol, looking at the border patrol as one of the largest police forces in the United States, and how they grew to be so large, and in particular, to target their resources against one population — which at that time was Mexican immigrants. It’s increasingly Central American and other non-white immigrants coming across the southern border.

We can pick up from our earlier conversation the U.S. Mexico War as being a war of conquest, of white settler conquest. We know that, at the end of that war, the United States could have taken all of Mexico. We were positioned to seize all of Mexico — we had occupied Mexico City and could have taken everything. But the United States negotiators decided that we didn’t want all of Mexico because we didn’t want Mexicans. We didn’t want that non-white population, Indigenous folks, Black folks. You have to remember, at this time people are conceptualizing Mexicans as being a so-called mongrel mixed breed of African, Indigenous, and Spanish. That African piece is huge in the minds of people in the 19th century. We’ve forgotten that now, but it’s huge in the minds of people at that point. So, the idea of having another Black population, non-white population, incorporated into the United States was anathema to the white settlers at this time period. They strategized to draw the U.S.-Mexico border in a place where they could get as much land as possible, with as few people as possible. So the U.S.-Mexico border is a racial border, it is imagined as being the divide between so-called white settler America and non-white Mexico.

My first book, Migra!, then goes on to tell the story of the establishment of the U.S. border, which was the police force that’s supposed to guard the line between so-called mongrel Mexico and white America. And that does a lot to help explain the rise of the U.S. Border Patrol and how it marshals all the resources — U.S. immigration, law enforcement — which could have been going to so many different things. I’m not saying they would have been good things, but could have done so many different things.

Going to hospitals to arrest immigrants who had become public charges. They could have done that, right? They could have targeted Chinese immigrants, in particular, who were living under the conditions of Chinese exclusion up until after World War II. They could have done a lot of things. But really the border patrol in its beginning, most of the border patrol officers were white men from the border region, mostly working class white men, who took that power of federal immigration law enforcement and said “No, we’re going to enforce this racial divide that comes between us in our communities here.” And they targeted Mexicans in particular.

It’s almost ironic, because up until that point there really were no rules being implemented against Mexican migrants. The border patrol started that story in 1924. Prior to that, people got a wink and a nod, Mexican immigrants largely coming across the border.

That’s my first book, Migra!. It tells a story of the rise of the U.S. border patrol and that form of racialized policing. I wrote that book because I grew up on the border in San Diego, California. I grew up watching the border patrol police our communities in the 1980s, before Operation Hold the Line. They’d come into our schools, our buses, our transit stations, and they’d snatch people up and take them away. I’m not from an immigrant family, but that terrified me, watching that happen. As I grew up I experienced, as a Black child, the War on Drugs, when they were coming into our schools and sitting us on curbs, arresting people after 10 p.m. I saw a lot of similarities to what was happening to Mexican immigrants and what was happening to us Black youth, and nobody was talking about what the intersections might be. So, I’ve really spent the last 30 years trying to figure out what are the origins and intersections of anti-Blackness and anti-immigrant activity in the United States. Migra! was my first investigation into all of that — how is it that the boys in blue could come for us and the boys in green went for them, and what is the relationship between all of that?

Then I went on to write a book called City of Inmates, which is about the rise of mass incarceration in Los Angeles. That really tracks the rise of this form of human caging from the origins of European conquest in Los Angeles of Indigenous lands — really its Native peoples in what is now known as LA who were the first people to be targeted for criminalization and policing and incarceration. When you tell the story of mass incarceration from that moment of occupation, of the criminalization of Indigenous communities, all of a sudden this regime that has grown looks like yes, it’s about labor control, absolutely. It’s about racial capitalism, absolutely. But it’s also about the stories of conquest and elimination that as the United States comes in, tries to remove Indigenous populations to literally eliminate them from the landscape.

Policing and incarceration are part of that story of elimination, and all non-white populations who come in to LA after that — LA is known as the Aryan city of the sun, the ideal white settler society in the late 19th century, early 20th century — all stories of incarceration following that are part of this cauldron of elimination. And why this is so important for Black folks, I will say this again and again, the history of Black folks in the American West is the canary in the coal mine for Black life in the United States. What happens when Black people, when we, have pushed ourselves into a region where there is no imagination for life whatsoever, and also no dependence upon our labor? The answer is elimination.

And that’s what we’ve seen with the rise of mass incarceration in Los Angeles and across the American West: Tthe answer for the impossibility of Black life in this white settler society is the rise of the carceral state to remove us from the streets, to remove us from our communities, to remove us from life. That’s what City of Inmates is about. It’s about a lot of things, but it’s about finding the intersections of Indigenous — what we now call BIPOC, Indigenous, people of color, Black folks — histories around the carceral state and how, at least in LA and across the America West, that begins with Indigenous removal. And now we have the story about Bad Mexicans, which is about this incredible group of rebels who challenged all of this.

I will say that many of the magonistas, when we talked about their fallibility earlier and see what are the other pieces or areas where they had a limited imagination, were around Asian immigrants, and Chinese immigrants in particular. During this time period, the magonistas would rail against capitalism and rail against multiple forms of racial inequality, but would target Chinese immigrants for exclusion and remove them.

But beyond all that, you have this incredible group of rebels who were more grappling with the issues of the day and trying to imagine something radically different. As someone who grew up in the borderlands, I was never told about them — I was never told about the radical history of Mexican immigrants and what that might mean for us young Black youth trying to organize with them. These were the stories that I wanted to hear, that I needed to know. That’s part of the very personal reasons why I write some of these stories.

Hagopian: That’s fascinating. Thank you for sharing that. There was a great question in the chat I thought I would just ask. And then Nancy, if you have a last one that you want to ask as well, that’d be cool. Someone asked if you’ve sold the film rights yet, and if we’re going to get to see this book on the big screen. Then we have another question, “I am attending this class from the city of Limerick, Ireland, birthplace of John or Juan [illegible] who was supposed to have fought and organized alongside Magón in global solidarity and action, in a time before the internet.” So, I just wanted to share that with you and thought that was awesome to hear, too. Did you have another question?

Mirabal: Yeah, I just wanted to circle back and give Kelly an opportunity to talk about the women in the magonistas, or women revolutionaries. So, anything that you’d like to discuss?

Lytle Hernández: Sure. Often when the magonistas are written about, Ricardo Flores Magón and the men are at the center of the story. I didn’t want to do that. I absolutely spent time thinking about it, doing the work to amplify and highlight the role of women. At minimum, and this is truly at minimum, when Ricardo Flores Magón is incarcerated — the so-called leader of La Junta, right? — it is women who hold the movement together. How do they do that? Well, they smuggle this rebel correspondence to him back and forth in jail. So, Ricardo Flores Magón is arrested in Los Angeles in August 1907, in this dramatic raid on a hideout at the edge of town, and he’s put into solitary confinement in the LA City and County jail.

From solitary confinement people expect him and the revolution to die — you take out the head of the revolution, the revolution is going to die, right? Not at all. How? Well Ricardo’s life partner, a woman named María Talavera Broussé, would come to the jail and say, “Oh, you know, I’m just his wife. I’m just a woman, and what I want to do is come in and wash his clothes for him. He’s got dirty clothes. I have to take care of my man.” Right? Well, she would pick up those dirty clothes, take them home, and then sew rebel correspondence into the seams of his pants and his underwear, and then send those clothes back into the jail. So that’s how she kept the rebel correspondence moving back and forth.

In June of 1908 — right before those big raids that trigger the response from the FBI — she also goes and visits Ricardo Flores Magón in the LA County Jail, and they’re talking in the visitors room, and Ricardo drops something and María sweeps her giant skirt around this note and puts it into her purse and runs out of the jail and smuggles what were effectively battle plans for the 1908 raids out of the LA County Jail and hands them to Práxedis Guerrero, the great fighter, who takes them and fights. María is just one of the examples. She did a whole lot more before Ricardo was incarcerated as well.

I want to tell you about one more woman who’s highlighted in this book and her name is Juana Belén Gutiérrez de Mendoza. Someone could put that in the chat for the folks: Juana Belén Gutiérrez de Mendoza. She is a brilliant autodidact, a queer woman from the mountains of Durango, who begins her rabble rousing as an advocate for miners in Mexico. She said they’re getting paid too little and they’re working too hard and she’s an advocate, and she’s arrested so many times in Mexico that she decides rather than signing her name on her jail slips — where it says you’re supposed to put your name — she starts to put “Sedition and Rebellion.” I love it. She starts to sign her name is “Sedition and Rebellion” and she joins up with Ricardo Flores Magón and others in Mexico City, and she launches an anarchist feminist newspaper called Vesper.

When they all have to flee and come to the United States, she comes with everybody and she continues to organize. When Ricardo Flores Magón begins to grow in power, and some people say that he should be the president following Porfirio Díaz, it’s Juana who says “No, we’re not here for any individual to replace Porfirio Díaz. We’re here for a set of principles.” She fights for those principles, and she and Ricardo really go toe-to-toe on this when nobody else is really willing to challenge Ricardo yet. She ends up leaving the magonistas because she and Ricardo go their separate ways. You know what she does next? She goes on to join Emiliano Zapata’s army, helps to ghostwrite his Plan de Ayala, and goes on for years as an advocate for women’s rights and workers’ rights in Mexico. She’s extraordinary.

Hagopian: Thank you so much. Dr. Hernández. Nancy, thank you so much for so many great questions that will help us all in the classroom to bring these stories to life with our students.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Audiogram

Here are a few reactions from participants:

What a wonderful topic! I so appreciate your connecting more necessary dots as we work to dispel harmful myths and reveal a more authentic American history.

I loved her discussion of the role of women in the movement. But also talking about: the founding of the FBI with the magonistas in 1908; the movement plans to give land to Black Americans and Indigenous communities; relating all this history to the carceral state today; referencing Du Bois’ “Global Color Line”. . . and . . . AND — she is a wonderful storyteller!!! Ain’t nothin’ better than someone who loves this history, knows this history, understands the interconnections, AND can tell it through wonderful stories. I forgot I was hungry. And that’s sayin’ a-lot!

Your expertise has fed me. The light you shine on the Mexican movement has brought me a sense of power, pride, and ganas! It is an honor to be in this space listening to your knowledge.

I will be thinking for a while about the phrase you said more than once: “When you tell the story of [a particular history] from that moment. . .” This will help me to think about what moments I am using in teaching — how can I help students better understand the subtext of U.S. history as it is told in our textbooks, as it is framed as a “story.” I wish I could take a class from you! Thank you!

Your work inspires and motivates me (and many other young scholars) to keep fighting and strive to bring to light and challenge the inequities we see in our communities.

Resources

Here are many of the lessons, books, articles, videos, and more recommended by the presenters and also by participants.

Lessons and Curricula

|

U.S. Mexico War: “We Take Nothing by Conquest, Thank God” by Bill Bigelow (lesson) Deportations on Trial: Mexican Americans During the Great Depression by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (lesson) The Line Between Us: Teaching About the Border and Mexican Immigration by Bill Bigelow (teaching guide) |

Related Books

|

In addition to Kelly Lytle Hernández’s Bad Mexicans: Race, Empire, and Revolution in the Borderlands, the following books were referenced: Still Dreaming / Seguimos soñando by Claudia Guadalupe Martínez, illustrated by Magdalena Mora, and translated by Luis Humberto Crosthwaite (Children’s Book Press) An African American and Latinx History of the United States by Paul Ortiz (Beacon Press) City of Inmates: Conquest, Rebellion, and the Rise of Human Caging in Los Angeles by Kelly Lytle Hernández (University of North Carolina Press) Harvest of Empire: A History of Latinos in America by Juan Gonzalez (Penguin Group) Migra!: A History of the U.S. Border Patrol by Kelly Lytle Hernández (University of California Press) “Revolutionary Women of Texas and Mexico: Portraits of Soldaderas, Saints, and Subversives” edited by Kathy Sosa, Ellen Riojas Clark and Jennifer Speed (Maverick Books) |

Related Articles and Podcast

|

““The Díaz Administration Is a Den of Thieves.” Political Activism in Turn-of-the-Century Mexico” by Kelly Lytle Hernández (Literary Hub) “Downplaying Deportations: How Textbooks Hide the Mass Expulsion of Mexican Americans During the Great Depression” by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (Zinn Education Project) “The Legacy of “Juan Crow” Lynching In Texas” by Énoa Gibson (Truth Be Told) “Katha Pollitt on How to Protect Abortion Rights and Kelly Lytle Hernandez on Bad Mexicans” from The Nation podcast Start Making Sense |

This Day In History

|

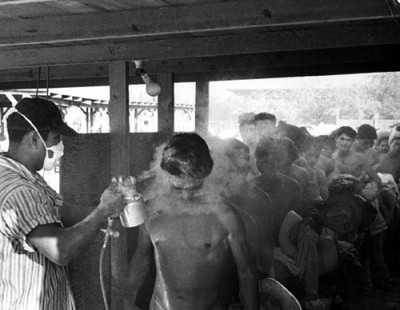

May 5: Rethinking Cinco de Mayo Sept. 14, 1911: El Primer Congreso Mexicanista Convenes in Laredo Jan. 28, 1917: The Bath Riots July 12, 1917: The Bisbee Deportation Jan. 28, 1918: Porvenir Massacre Feb. 26, 1931: La Placita Raid Jan. 31, 1938: Emma Tenayuca Leads Pecan Sheller Strike |

Listen to an interview with Lytle Hernández about Bad Mexicans: Race, Empire, and Revolution in the Borderlands on Democracy Now!

Participant Reflections

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

Another example of people — magonistas — not just lying down and allowing abuse. There are thousands of stories of rebellion. They have to be taught. I also love the inclusion of women in these stories. It is important that everyone sees themselves in stories of resistance against oppressive systems.

So many historical and political connections! Such passion! This turned out to be one of my favorite sessions. Prof. Hernandez is an amazing person — historian, teacher, speaker, organizer, inspiration. Her creative and clear analysis — ‘white settler state,’ Juan Crow, etc. — and wonderful stories at the end about women in the movement. Terrific.

Although I know about the Mexican Revolution, the magonistas were completely new to me and it reminded me that there is always a precursor to a revolution/rebellion and needs to be studied.

The minimization of Mexican American history and the deep connection between movements against white supremacy.

Learning about Ricardo Flores Magón and Juana Belén Gutiérrez de Mendoza, and about the IWW in the Southwest.

That Black Americans often followed international revolutionary movements — since these movements provided different frameworks that could be used in their fight for freedom.

The link between Black Americans and Mexicans/Mexican Americans looking to each other as inspiration; Juan Crow which is not covered in U.S. history textbooks as it should be.

How this history IS also American History and deserves to be taught as part of the “canon.”

How badass Juana Belén Gutiérrez de Mendoza was!!! And also sitting with a lot of gratitude for revolutionaries of all times and experiences. The threads that Dr. Lytle Hernández’s conversation sparked particularly for me and the parallels of the Haitian Revolution is inspiring.

The connection between the labor movements in the U.S. and in Mexico. The power of a shared story to spark a revolution.

The history of rebellion and resistance is American history, especially as it relates to white settler colonialism in the American west. Additionally, how mass incarceration and State and Federal law enforcement (the FBI) was shaped by the magonistas.

What will you do with what you learned?

I can use it in my high school American History classes. It compares to the current (and radical) Liberation Theology Movement in Mexico, Central, and South America, which seems to be on the same continuum of redistributing land, money, and resources to IP and other marginalized peoples.

Bad Mexicans will be a choice for book clubs in my Modern U.S. History class.

I’m completely rethinking my unit on the Mexican Revolution! My course is two-year, and I will begin by drawing connections/parallels between Jim and Juan Crow.

Incorporate it into my new Black & Latino Studies course I’ll be teaching in the Fall!

[I will] include more stories of cross-racial solidarity in my teaching.

To focus on the organizations; the putting on the pedestal of leaders is always a poor tactic as through the prism of today they appeared flawed. However the organizations and the solidarity are real lessons about what our students can do today.

At a school of 60% Latinx and 35% Black American students, I see this as an opportunity to share the significance of their stories as being overlapped and integral to each other.

I intend to encourage my middle school cohort to make a play about Juana Belén Gutiérrez de Mendoza!

Include the “rebel history” of those that impact American history and challenge the white manifest destiny narrative.

Presenters

Kelly Lytle Hernández holds the Thomas E. Lifka Endowed Chair in History and directs the Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies at UCLA. A 2019 MacArthur fellow, she is the author of Bad Mexicans: Race, Empire, and Revolution in the Borderlands, Migra!: A History of the U.S. Border Patrol and City of Inmates: Conquest, Rebellion, and the Rise of Human Caging in Los Angeles.

Nancy Raquel Mirabal is associate professor of American Studies and the Director of the U.S. Latina/o Studies Program at the University of Maryland, College Park and a board member of Teaching for Change. Mirabal is the author of Suspect Freedoms: The Racial and Sexual Politics of Cubanidad in New York, 1823-1957; first editor of Technofuturos: Critical Interventions in Latina/o Studies and co-editor of Keywords for Latina/o Studies.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn