On March 4, 2024, musicologist and music historian Guthrie P. Ramsey Jr. joined Rethinking Schools editor and high school teacher Jesse Hagopian to discuss his book, Who Hears Here?: On Black Music, Pasts and Present.

On March 4, 2024, musicologist and music historian Guthrie P. Ramsey Jr. joined Rethinking Schools editor and high school teacher Jesse Hagopian to discuss his book, Who Hears Here?: On Black Music, Pasts and Present.

This session was the latest in our monthly Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online class series. Don’t miss the rest of the spring lineup — register now.

Participants shared what they learned and the impact of the session:

I was reminded about the power of music to motivate, communicate, influence, share stories, and tell history. There are just so many ways that music helps connect the dots of the world.

Thank you so much for tonight. I’d had a tough couple of weeks and nearly changed my mind about attending due to flat-out mental exhaustion, but I am so glad I decided to be here. This whole experience fed my soul in a very needed way.

Music does cultural work but without words.

That enslaved people used music to communicate and build community, and sometimes they used coded messages with or without words to communicate in ways that the owners wouldn’t understand. I’m very interested in the community that was created in this way and how protest music did the same.

Music can serve as a connector between people, history, and culture in very subtle ways.

I was taken back to the history of music in my own family. I can use the understanding of how they channeled their pain through that music and teach that to young people today.

This was one of the best Teach the Black Freedom Struggle classes I’ve been to! Very engaging and I learned a great deal.

Video Clips

Select clips from the class.

Black women as primary drivers of Black music, exemplified by Alice Coltrane:

Music making as an avenue of resistance and community building for enslaved people:

Jazz and Black music columns in the Jim Crow era:

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Alright everybody, welcome. A supreme love to you all, and to our special guest this evening. I’m so excited for our workshop this evening. Happy women’s history month everybody. On behalf of the Zinn Education Project, we would like to welcome everybody to our class with Guthrie P. Ramsey Jr.. My name is Jesse Hagopian, or when I’m on stage playing with my blues band, J. D. Lenoir. I work with the Zinn Education Project, and I’m an editor with Rethinking Schools magazine.

We hope that you all have dropped in the chat where you’re Zooming in from and why you’re joining us for the class this evening. We would love to get to know who’s in the room. Some of you are joining us for the first time. Welcome to you all. And many of you have participated ever since we first launched this series. It’s really a gift, it’s a love supreme, to get to have this time together. So thank you for being in virtual community with us.

Today’s class is hosted by the Zinn Education Project, which is coordinated by Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change. It’s part of our Teaching for Black Lives campaign. We have members here from our Teaching for Black Lives study groups, so if you’re in one of those groups, please add T4BL after your name on your Zoom screen. And folks should know that we offer free, downloadable people’s history lessons that many of you have used for middle and high school classrooms at the Zinn Education Project website.

Before we jump into this conversation, we want to find out who’s in the room and go through our plans together. So we’ll post a quick poll to find out who’s with us this evening — teachers, educators, librarians, teacher educators, historians, parents, students, others in the room with us. So let us know. And if you have multiple roles, just pick your primary role. Just a few quick notes about our format. Today we are blessed to have ASL interpretation provided by Kara Colbert and Krystal Butler. I’m not sure if it’s also Kara Colbert this evening. Maybe we’re also joined by Rodney Lebron. Krystal and Rodney, thank you so much.

At the end of the session we ask for your feedback. We read every word. We also ask that if you need PD credit, you can request that with the feedback form. The resources listed in the chat will be sent to you all in about a week. So please drop any resources that you all have that connect with tonight’s theme. Halfway through our discussion this evening we’re going to pause so you can meet each other and talk in small groups and share your thoughts with what you’ve learned in the discussion, and how you might apply it to your own classroom. Then we’ll return back with our speaker. Please share what you’re learning this evening on social media. You can tag the Zinn Ed Project at @ZinnEdProject. After about 25 minutes we’ll pause so that you can meet each other and talk in small groups and let us know what you’ve learned.

So, let’s look at the results of the poll. We have almost 40% K–12 teachers in the house. Welcome. We have 4% K–12 students. We have 3% family members to students. We have 27% teacher educators, 2% historians, and 2% librarians. So great to have you all with us for this important conversation.

I am happy now to welcome award-winning musicologist and music historian Guthrie P. Ramsey Jr. to discuss his book, Who Hears Here?: On Black Music, Pasts and Present. Y’all need to pick this up. Welcome, thanks for joining us.

Guthrie P. Ramsey Jr.: Thank you very much. I’m so happy to be here. As a former public school teacher myself, before the days of the professor gig, I remember well teaching K through 12 students in the Lawndale district of Chicago, which was per capita, at that time, the poorest neighborhood in the United States. Listen, this was in the mid eighties, and I’ll never forget this moment where a sixth grader came into one of my classes (because they changed out every period) and she had one of those Right On! magazines. You know, the fan magazines from that point. And Salt-N-Pepa were on the cover. She sat down in the seat and said, “Mr. Ramsey, Salt-N-Pepa are perfect.”

Hagopian: I love it!

Ramsey: Out of the blue, right before going to graduate school for music history and musicology.

Hagopian: Well, I want to dive into the book. Brilliant work that I really appreciate and learn so much from. You write that, quote, “Black music has been intrinsically linked to our understanding of Blackness writ large as a knowable, learnable, and teachable face of social reality and identity.” So, why has Black identity been so closely associated with Black musical traditions?

Ramsey: Well, the thing about Black music in the United States is that it has had basically two lives. The first is that it has grown from the relationship of Black people, displaced Africans, to their new social environment. It became perhaps the first expressive cultural practice that all of these people from different areas of and different tribal groups, and groups became one people. It was through this emerging system of musical traditions that we became one people. But at the same time, ever since the Middle Passage, this music has also been one of the most profound sites of interracial interaction. So, from the very beginning, it’s been a group American project. But because of African Americans’ unique relationship to that, we think about it as socially tied to the history of African Americans.

Hagopian: Thank you for that. I might have a lot to process and work through as I push back. Oh, I like that. I like that. I think it’s absolutely right that we . . . and I don’t think it gets framed like that that often. But I think you’re right. It’s fascinating. You also write about the lack of Black scholars in the academic musical disciplines and how that shapes our understanding of music. So, I was hoping we could disturb that silence today and talk about what’s missing from the literature on Black music, because Black writers and theorists’ voices have too often been muted in the investigation and significance of Black music.

Ramsey: Well, I’d like the participants to understand that this is not a typical monograph that you have in your hands. This is a group of essays that were written between 1996 and 2019. Whenever you are looking at one of the essays, it’s very important to look at when I wrote it, because those essays are about the moment that I was writing them. So that particular essay that you’re referencing was about a time in music studies where a lot about social identities were being talked about as part of the analytic process. This is in the 1990s. And what I noticed, as a music historian and musicologist, is that while all of this identity work was being done, there were very few African Americans participating in the discourse. So, while I believe that music history is an open field where music can absorb any connotation that you want to ascribe to it, because it’s an abstract arc, it goes beyond the truth claim of the lyric. It’s something that signifies meaning to people, and they always interpret that meaning from the social position that they have. And that’s perfectly fine. But if you have an entire group of people left out of that equation, what you’re missing are the perspectives that they may bring to the conversation that will enlarge all of our ideas about what this music means, particularly if the thing that’s driving your analysis is this idea of understanding social identities vis-a-vis these musical practices.

Hagopian: Yeah, no doubt. Well, one of the things I’m excited about is actually getting to play some music, and having us all listen to it and reflect on it and get your thoughts. So we’ll do that in just a second. But, our session was called The History of Black Music — A Love Supreme. So I definitely wanted to reference John Coltrane, but also understand that his wife, Alice Coltrane, was also one of the most significant musicians who explored the connection between music, spirituality, and jazz. I think that we often hear a lot less about Alice Coltrane, so I think it’d be great for us to take a minute and listen to some of her music. So, we have a clip from her harp solo at the Jazz Jamboree in 1987, and then we’ll talk on the other side of it.

Ramsey: Well, let’s start first with the latter question, because it should be made clear that Black women have been the primary drivers of Black music making, Black music study, and Black music criticism for a very long time. I have traced some of this history from the nineteenth century, where, if we just start with the period right after emancipation, you had the Hyers sisters who were from California, who created and helped to create the first Black musical that will ever happen in the United States. In the 1870s in Boston it was called Out of Bondage. It was a meditation on the slave era. From the slave era up to freedom you had a time in the late 19th century where it was very much in vogue to have these Black operatic divas, these women who did concerts singing western art music. It was a vogue that happened in the late 19th century.

One of the greatest ones was Sissieretta Jones, who traveled throughout South America and the Caribbean in the 1880s and 1890s as a very young woman. She did that until about age 29, and she started touring about age 18. She did not do anything close to minstrelsy, which was the prevailing popular music culture at that time. She didn’t do anything with that until she said, “Well, I’ve got to make some money because the Black prima donna thing is waning.” And she went and made some money. This has been a long thing, and not to mention all of the women who were music critics and music teachers and music activists and educators. So women have been a major driver of this story for many years now.

What happens to that scenario, when you marry one of the most famous jazz musicians that we know. In fact, Alice Coltrane was a full blown bebop pianist when she met John Coltrane. Because of her background in the church, she could do gospel music. She could do bebop. She was a phenomenal musician in and of herself, but she got together with John Coltrane and she just decided that she would support his musical aspirations, including being a major force behind the spirituality that he embraced near the end of his life. And, of course, she continued that work on her own.

Hagopian: What a fascinating figure, and in so many ways — from her just musical genius to her spiritual beliefs — I can imagine some incredible lessons developed around John Coltrane and Alice Coltrane from some of the educators with us in this room today. So I hope we see some of those developed because there’s so much good music to share with students on that.

Ramsey: One of the things I think it would be important to talk about in that context is the fact that she’s playing a harp. You could start with your students thinking about why or how the harp fits into the history of jazz. There are not a lot of harp players in the history of jazz. So the question becomes, what does it mean to play as a kind of outsider? What does it mean to have an individualized voice that you’re trying to fit into a tradition that may or not may not be open to your presence as a woman? And then you’re a woman bringing a harp into the sound, too. So this could be a really marvelous lesson about resistance, about how to be an individual, and how to find one’s voice in a tradition that may not be used to your voice. I can see a lot of great lessons coming out of that.

Hagopian: I love all those ideas. Thank you. I think you sparked some new lessons. Thank you for that. I wanted to get into the section of your book called Slavery, Culture, and the Black Atlantic, where you write that “despite the developments of laws and social practices designed to keep Black slaves subservient, they nonetheless asserted their aspirations, their senses of beauty and the sublime, their frustrations, pain, and humanity, through sound organization.” Can you tell us more about how making music became an avenue of resistance and community-building for enslaved people in the United States?

Ramsey: One of the first things to think about is that when the enslaved were brought to the shores they had with them memories of musical practices, myths, rituals, and ways of being that were part of who they were. It was part of the materiality of their existence. But they immediately met another cultural norm that was enforced and sometimes enforced through violence. So it was always going to be a negotiation, one in which you had to be savvy, one in which you had to create in a context that was not hospitable sometimes to your humanity, to your idea about who you believe you were in the world. The thing about early Black music making in the enslaved communities is that some of the ways in which it was presented to the outside was completely benign. It was just entertainment, because it was entertainment for everybody involved, for the enslavers as well as the enslaved.

But the music was used too, sometimes to give messages that could not be spoken out loud. It was used to, most importantly, create social bonds with one another so that in the practice of making sound together people began to think about themselves as one people. Music could do this cultural work without words sometimes, and sometimes without words that were not to be taking efforts at face value. So there was a lot of subversive messages going on, not only in the text, in the lyrics that were being sung, but also in the fact that they were making sounds that had not been heard before in this context. So this idea of putting all your life force into sound organization and having it be not only a space for creating a social bond with your compatriots, but also a way to be misinterpreted by people who don’t have your best interests at heart. It was performing a lot of functions in that environment.

Hagopian: Yeah, no doubt. I love the thought of subversive lyrics with double meanings being sung and played in front of enslavers who didn’t know that they were being mocked or ridiculed. I also find it fascinating that drumming was often outlawed by enslavers, even though they wanted some forms of music to flourish, to entertain themselves, or just to help enslaved people pass the time.

Ramsey: Well, here’s what we can remember about the sounds that were being heard in that context. There was some parts of the, let’s call it the “contraband music,” because the first people who were freed were from South Carolina’s Sea Islands because of the capture of the fort. I’m losing the name of the fort, the place where the Union army captured as a strategic move. Thank you so much, Fort Sumter. It became a place where all of these Northerners came down, because this is a way they can finally get to educate and learn. Then they heard this music. Like, “Oh my God, the singing is beautiful.” The things that they were singing, the melodies. Some of the fervor was accepted, but when they started all of the drumming, and then the rhythms and the dancing and the bodily aspects of it, sometimes those were like, “Oh, wait, wait, wait! This is a little too much!” Then, what was not necessarily in that context, but in other contexts where people were still under the law, what people gravitated to and praised was the things that sounded most like western music. What was tried, what was suppressed and written about as barbaric or heathenish was the rhythms, the dancing, and things like that. So it was. What you experience was checkered, lost here, lost there, just like the loss that created slavery. It was just not one thing, it was a lot of different things at different moments that created the situation.

Hagopian: No doubt. Then, the period after the Civil War is fascinating, and we have a campaign at the Zinn Education Project devoted to teaching about Reconstruction. It’s full of stories that show us how formerly enslaved people really expanded the meaning of freedom in this country in so many ways. That includes about how Black communities poured themselves into education and creative pursuits, including music You’ve studied ensembles like the Jubilee Singers of Fisk University, an HBCU in Tennessee. You’ve written about that music from scholars like James Monroe Trotter, who published Music and Some Highly Musical People in 1878. Could you talk to us about the surge of Black music during the Reconstruction period and the significance of that?

Ramsey: This was really fascinating about that moment. I love the late 19th century because those people were just amazing. They were able to create. What I’ve been thinking about recently is how, during Reconstruction, or during and after Reconstruction, the most popular music of the United States was Blackface. That was pop music. That was the thing that people wanted to hear, circulating the sheet music. As soon as recordings came into play in the last decade of the 19th century. They call them coon songs, and songs from the minstrelsy tradition were selling like hotcakes. So what are you doing? What are you going to do if you’re a Black musician. Whether you had some formal training in classical music, or whether you were someone enjoying the tent show at age 14, and started touring based on your raw talent, you always had to deal with minstrelsy. If you wanted to make some money you had to sing one of those songs. If you wanted to make some money you had to Blacken up. It was like auto tune. If you want to make a hit record, put some auto tune on. [Then it’s] Black enough. You heard it here first, folks.

But what I mean is, it was like the common practice, it was the thing that when you heard it you knew was about pop music. Now, the counter balance to that was that while particularly the musicians who were in Black musical theater, that first decade of Black musical theater — which was the main way that you could be in show business — you had to write a show, choreograph the show, put dancing Cake Walkers in it. You had to flirt a little bit with minstrelsy so people would want to pay to buy the ticket.

But they began to change the story in the 1890s, and throughout the early 1900s. By the time you get to the 1920s, you can have a Broadway show like shuffle Along with Blake and Sissle. They gradually got out of the minstrel thing. Here’s what I think is very important for educators looking back to this moment is that you cannot bring your 21st century sensibilities and judge people about what they were doing back then. You can’t come in and just start criticizing the use of minstrel songs and coon songs because it actually opened doors for people to be able to establish careers, where they then could work from inside of the industry to change it. If you were not engaging in some of the things that we particularly would today find offensive, you would not have had a career. You would’ve been shining shoes rather than touring around.

Another thing that you could really hang your hat on is that Black women were in the forefront of this thing, those Black musicals were popular, because you had these people doing these popular dances like the Buck and Wing and the Cake Walk. Those finales and those shows were so overwhelmingly beautiful during Reconstruction, that right after Reconstruction someone like Ziegfeld would see one of those shows and say, “I want to buy that finale out of the show. I need that. I need that in my show.” And he bought it, bought the rights to it, put it in the Ziegfeld follies of 1914 and never gave them back.

Hagopian: It’s just a really fascinating history, and especially how Black people navigated Minstrelsy, and used parts and sometimes appropriated parts, and then changed it themselves. So I appreciate you diving into that. Maybe we’ll take one more quick question before we head to breakout rooms. Then we’re going to play some music when we get back from the breakout rooms.

Looking at the Jim Crow era, you write about how the development and the heightened interest in jazz as an artistic pursuit posed a serious challenge to one of the central tenants of the American caste system, [that of] racial inferiority. You cite a Chicago Defender editorial called “Jazzing Away Prejudice,” which argued that jazz music could serve as an engine for the cause of racial equality. But you also know that this sort of open support for jazz was rare in the Black press at the time. So I was hoping you could tell us more about the significance of “Jazzing Away Prejudice” and how the Chicago Defender differed from some of the other Black publications in their approach to music commentary in that period. It’d just be great to get a better sense of some of the topics that Black music columnists focused on at the time.

Ramsey: The Black press was so important in not only documenting what was going on in Black communities, but also in the dissemination of this information so that people around the country could think about themselves as being one nation within a nation. That’s one way to think about it. And to think about the Black press is to think about what was the purpose of many of the people who were the founders of these publications. They often were people who believed in this uplift idea that you had to kind of perform a certain way in public or else you’re not being a credit to the race. There was that pressure. So, consequently, many, many of the people who could become music critics because of their educational background also promoted this idea that Black people participating in western art, music, or classical music was a higher calling than participating in jazz and things like that.

Now, I can’t remember what that writer was writing about. It could possibly have been the James Reese Europe band, which had just returned from an overseas stint and returned to the United States to great acclaim. The difference was the artists who were doing jazz put pressure on what you might call the elites, because when the music became so popular you had to, and the people and the public loved these artists. You had to give it up to them, even if you wanted to only cover what was going on in the classical world — meaning Black people who were playing classical recitals and things like that, and composers, which was primarily what was covered in the Black press — it was only in maybe the 1930s and 1940s, and certainly in the 1950s, where jazz, R&B, and rock began to supersede what was going on in the classical world.

Again, it’s about who’s doing the writing. What are their values? You can’t really just save the Black press. You have to say, “Okay, well, who is this critic? Who’s this by? Who does this byline belong to? What is their background? What agenda are they pushing? What organizations do they belong to?” You read some of those commentaries and they’re covering every recital that happened on Sunday afternoon at 3:30, and nobody played a bad note.

Hagopian: Right on. Thank you so much for this conversation.

[breakout rooms]

I hope everybody had a great conversation in your breakout rooms. We did. I just got a history of dance. I was lucky enough to be in Cierra’s breakout room, who just broke down the history of Black dance and modern dancing. That was phenomenal. I hope yours was as well. Welcome back! We’d love to hear what you discussed, so share in the chat. You can shout out your group and share highlights of your discussion. We’d love to know what you all came up with and what you thought of the discussion and how you might use this in your classroom.

Professor Ramsey, I want to jump back into the conversation, and I’m excited to share some music with the group. You write about how the period between the 1940s and 1960s was a watershed moment for Black politics and culture, which included the decolonization in Africa, the gradual desegregation of the music industry, the Civil Rights Movement, and really so much more. One of the most dramatic developments in music was when musicians began to literally play the blues. As a blues musician, a harmonica player, hearing Little Walter, or hearing Sonny Boy Williamson, electrify the blues harmonica like that, to me that sound is just sublime. It transformed music.

So, we want to play a couple of performances for you to comment on by a couple of iconic artists. Sister Rosetta Tharpe performing “This Little Light of Mine.” Then we’re going to hear Muddy Waters in 1965 performing “You Can’t Lose What You Ain’t Never Had.” Oh, I love that. Talk to us more about the electrification of the blues, including some of the pioneers like Sister Rosetta Tharpe, the trajectory of this music, and maybe also about how the desegregation of the music industry began.

The first, “This Little Light of Mine, I Want to Let it Shine” comes out of the spiritual tradition. The other piece, “You Can’t Lose What You Never Had,” is a traditional, I would call that maybe even not quite jump blues. It’s a style of blues [called] urban blues. Now those pieces, although they use the electric guitar as the emotional focal point in each piece, they actually belong to two separate genres. One was like a spiritual song done in a blues pattern, and one is an early rock [piece]. This was at a moment where things were really in flux, and you could have a lot of tributaries running through the music industry, through a piece of music that the music industry hadn’t yet cordoned off into a sellable piece, something that is contained so that you can separate people from their money, if you name it something right and put it into a category.

Now let’s think about gender and sexuality in these pieces. When the blues became electric and those artists like Muddy Waters, Blue Water, and all of these people, I began to play it. It was seen in the music industry as the mark of male virility and sexuality, in particular Black male virility and sexuality. That this was it became a key symbol that would quickly be adapted by the Mod crew in Great Britain and served back as a form of [illegible]. That was actually a derivative of what had been going on in the United States, but that was a very, very important turning point — the electrification of the blues — because it actually created a separate genre than the previous one — just by plugging in. Then that big, I don’t want to use the word [as] I’m being recorded, so I’ll use this. It became a sign of virility, let’s put it that way. So you got a big phallic symbol in your hand and you’re waving it around and you’re playing, you’re bending these notes, and it’s louder and it’s emphatic and it’s pounding. Some of those songs are about braggadocio. It became symbolic of Black male virility.

Now let’s see what’s happening with Rosetta Tharpe in terms of gender, sexuality, and race in the church. She’s a musician that was trained in a sacred environment in the tenth circuit, and travels with her mother, who, I believe, was a preacher. She’s actually a precursor to what the men were doing with the guitar. So she was the pioneer, but it became usurped by the male artists. As I said earlier, music is able to absorb whatever connotation you wish to give it. So it became in the industry a symbol of Black male virility based on innovations that I want to have done. Then you add to that fact that I believe she had a woman as a live-in partner. So what does that mean to have a woman who is a lesbian playing a phallic symbol in a more virtuosic fashion? If you compare both of their techniques, she’s actually playing more notes per measure than he was. He was playing it slower, kind of bending, a lot more bent notes. So, I mean, that’s a point of comparison that you can run your students through.

Hagopian: Fascinating! I just love Sister Rosetta Tharpe. I mean, the things that she’s doing on the guitar are innovating blues, developing rock and roll music. It’s just incredible to think about when you see how little she’s known as a progenitor of rock and roll. So thank you for sharing all that. I want to dive just a little deeper on the blues, because I recently finished LeRoi Jones’s (Amiri Baraka’s) book called Blues People and that is an incredible book, too. You write about how it was the first book length study by a Black author to theorize extensively about the relationship between Black music’s development and the historical trajectory of African American social progress. You note that one writer called Blues People quote “the founding document of contemporary cultural studies in America.” I think you also had some divergent opinions from it as well. I’m really curious about your analysis of Baraka’s argument about why Black people are blues people.

Ramsey: Well, I’ll start with what I disagree with. First of all, full disclosure, Amiri Baraka was my father-in-law. I should say that before I start talking about it. I think the thing that I was troubled with when I wrote that piece earlier in my career. . . That’s another thing about this book, if you read the essays straight through, at the beginning of my career I was talking straight to my colleagues, then by the 1990s, by the time you get to 2019, I think about myself as writing for a larger audience. So that’s something to take into account as you read the essays. The thing that I disagree with him [Baraka] on was his points about commercialism and his points about the relationship of Black people to the Black church. I thought that at the point that he was making that argument in the early 1960s, there were some points that he was trying to make about social class, about religious repression, and things like that. So he had to make those kinds of arguments. But, from the point of view that I have today, I don’t upgrade musicians for trying to make a living playing music. I don’t care what period I’m looking at, because I don’t think people have to make the art that I want them to make. You could you buy it or not, you teach it or not, and that’s how it goes.

The thing about the Black church is, even if you think about the world that he was traveling in at that time, it would have been not important to talk about the Black church as a modern entity. But today, we understand it is being the bedrock of so much that we think about as Black and male today. And when I call it the founding document of cultural studies, cultural studies is this idea of understanding what historical actors have been doing. What are their motivations and what are the repercussions of what it is that they did? Meaning, how did it really resonate out? And this is what Amiri Baraka did with Blues People, he took in the entire history of Black sound and let us see that by understanding the music we can understand the history of the people.

Hagopian: I would recommend people check it out. I think there’s some rich content in there that could be used to develop lessons in the classroom. Also Blues Legacies and Black Feminism by Angela Davis is one I just started getting into. I’m really excited about that as well. But I think we have time for one last question before we move to the evaluation, and I was hoping you could speak to the tradition of Black protest music, as exemplified in a couple of clips I want to share with you. The first one is by an artist from the mid-20th century, and his family was enslaved on the same plantation as my family. My dad recently discovered this through a lot of his genealogy and research, and I actually wrote a song [see the third video below] that maybe we’ll share at the very end if we have time while people are doing the evaluations. I wrote the song as a tribute to him, J. B. Lenoir, and my ancestors on that plantation. Then the the second clip that we’re going to show is a recent rendition of a freedom song from the Civil Rights Movement. I’d love to hear your thoughts on those.

Hagopian: Yeah, it was. It was actually a Swedish couple in Chicago that found him, and they were trying to get him on a Swedish TV program. So they recorded that and I think that it never actually aired on Swedish TV. But they found the footage.

Ramsey: And by what do you mean, they found him?

Hagopian: They were going to clubs in Chicago, the Swedish couple, and he was already playing. He had played with “Big Mama” Thornton and toured Europe, and he had played quite a bit. But they were really excited by his playing when they saw it, and they said we should get you on TV in Sweden.

Ramsey: Whenever you’re teaching some of these clips, it’s very important to tell your students the context of the clip that you’re watching so that you don’t naturalize this idea, and this is so important today because students are always encountering random visual things from around the world instantly, so as we use this media in our classrooms, one of the ways to distinguish their everyday experience with media — which is through their phones and constantly scrolling, 30 second clips or 1 minute clips — that we make our experience a little different, so that they can know that they’re in a different realm instead of just not taking things in. But without critique, without understanding the original context — because it’s real easy to teach the blues as this timeless marker of Blackness, when actually the last four clips are all blues, but all four are quite different. The context is quite different. And that’s what educators can do: We can show people that context matters. And particularly, it’s important.

I love the use of language he has found, because there is this idea that people are still quote unquote “discovering things” that people know about already. But they don’t know about it, so it becomes discoverable. I think that kind of language, I love when people use it because it opens up a conversation. If they don’t use it, I can’t open up the conversation. It just looks like I have these in my bonnet, you know what I mean?

There was a question in the chat that I think really is urgent. That was, how do I feel about white people teaching Black music? And I really want to address that because in most cases the music that we teach are commodified objects, they’re objects that the musicians themselves put in the marketplace to be sold and marketed, purchased and consumed. And the more people do that the better. I ended my teaching career about three years ago, but when I stopped the term ‘cultural appropriation’ was on everybody’s mind. I mean it was almost an epidemic. And this idea of people being concerned about cultural appropriation? What I’d like to submit is that when you talk about anything, that cultural appropriation talk, this idea that, “Well, how I began my talk, this thing called Black music has been part of the American context since the Middle Passage.” Just because they just dropped a country western [illegible] two weeks ago, the process of cross-cultural dialogue has been going on since the boats came over with Black people on them. I stand on this conviction that you can’t put things in the world and call it the greatest thing ever, and then try to police who engages [with it]. What you can do, though, is demand that the people who created it are getting the equal money that everybody else is getting, meaning you can’t have uneven power relationships within the consumption of it. But you can have cultural sharing, which is why it’s put in the world anyway. I don’t know one musician who says I just dropped this album and I only want xyz people to purchase it. “You can’t pay $175 to come into my concert because you’re the wrong type of person.” No, you can’t. I don’t understand how you hold those two ideas.

Hagopian: I greatly appreciate that perspective. I think it’s one that we need to have more and more dialogue with our students about, like equal payment and treatment and coverage, but also the music has always been about sharing and mixing and coming up with new experiments from different cultures. So thank you. I can’t thank you enough for all that I’ve learned this evening, and all that you’ve shared with us. It’s been a remarkable conversation. We have to cut it there, because people need time to fill out the evaluation form, but maybe everybody could unmute and give your thank you to Professor Ramsey.

Ramsey: And to our ASL interpreters and everybody!

Hagopian: Yeah. And Professor Ramsey has another book coming out next year, so we’re excited for that. Thank you, everybody. I hope you have a wonderful evening, and we’ll see you at the next class.

Ramsey: Thank you.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audiogram

In this audiogram, Guthrie P. Ramsey Jr. discusses Black women as primary drivers of Black music, exemplified by jazz harpist and pianist Alice Coltrane.

Resources

Many of the lessons, books, and other resources recommended by the presenters and participants.

Books and Articles

| In addition to Who Hears Here?: On Black Music, Pasts and Present, the following books and articles were referenced.

Black AF History: The Un-Whitewashed Story of America by Michael Harriot (Dey Street Books) Blues People by Amiri Baraka (aka Leroi Jones) (Harper Perennial) Hip Hop Speaks to Children: A Celebration of Poetry with a Beat edited by Nikki Giovanni When the Beat Was Born: DJ Kool Herc and the Creation of Hip Hop by Laban Carrick Hill Music and Some Highly Musical People by James Monroe Trotter (Createspace Independent Publishing Platform) “Black Artistry is Woven into the Fabric of Country Music. It Belongs to Everyone” by Rhiannon Giddens (The Guardian) “School Days: Hail, Hail, Rock ‘n’ Roll!” by Rick Mitchell (Rethinking Schools)

|

Videos

Curricula

|

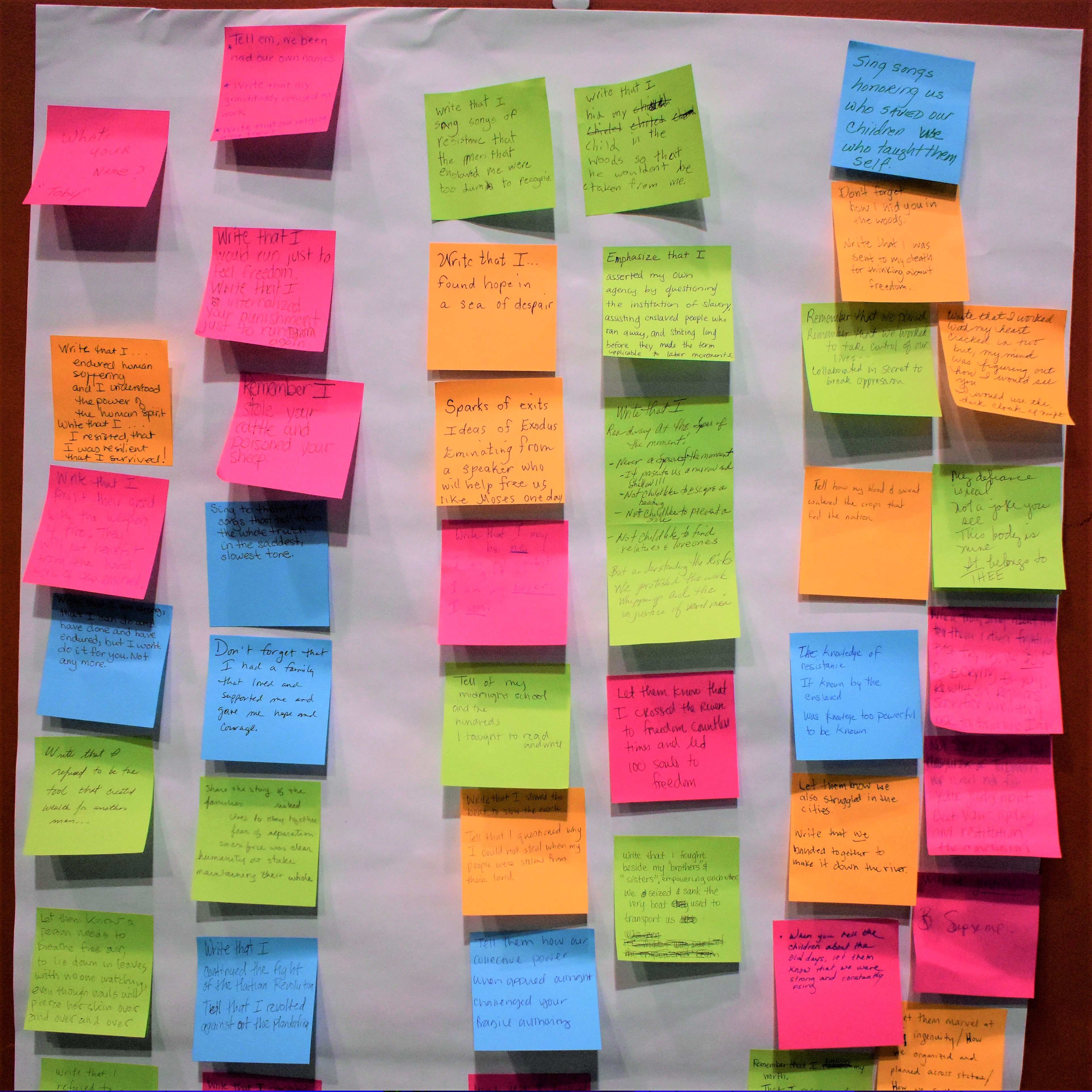

Poetry of Defiance: How the Enslaved Resisted lesson by Adam Sanchez Sun City: Artists United Against Apartheid teaching guide by Bill Bigelow Teach Reconstruction Campaign, a collection of lessons, books and films, student projects, and a national report on teaching Reconstruction |

Additional Resources

|

The Story Of ‘A Love Supreme’, (from NPR’s All Things Considered) Alice Coltrane, a comprehensive website of the life of Alice Coltrane |

This Day In History

The dates below come from our This Day in People’s History collection, which contains hundreds of entries all searchable by date, state, theme, and keywords.

|

April 9, 1898: Paul Robeson Born Feb. 12, 1900: “Lift Every Voice and Sing” Was First Publicly Performed May 5, 1905: Chicago Defender Founded April 7, 1915: Billie Holiday Born Sept. 23, 1926: John Coltrane Born Aug. 11, 1973: Hip Hop Born |

Participant Reflections

With more than 170 attendees present, the conversation and chat was lively, engaging, and full of history, teaching ideas, and more. Polls showed participants included 38% K–12 teachers and 27% teacher educators, with students, historians, librarians, and more also present.

See below for more comments that participants shared in their end-of-session evaluation.

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

I really liked the way music and video clips were interspersed throughout the session without disrupting the flow of the conversation. As someone who grew up listening to my parents’ album collection (especially Motown), I appreciated how Professor Ramsey explained at the beginning of his talk that not only is Black music a unique cultural force in its own right, it has served as a bridge across cultures.

The coded and subversive nature of Black music was very interesting to think about.

The impact of Black women in music in the social justice movement. Something I should have been taught in school and will address as an educator.

The reach music has beyond its time/space to touch us in ways that other types of storytelling don’t have.

Listening to the many ways to utilize music in the classroom and just being reminded where the many types/ genres of music started and how they continue to evolve.

That music can create social bonds, especially in the establishment of African American culture where it was said that if you practice sounds together you can see yourselves as one people.

It was great! Loved the music snippets.

I loved the timing and feel I have a great jumping off point for more resources and research!

What will you do with what you learned?

Alice Coltrane playing the harp almost took me out! I can’t wait to share this with my students. I love to add women who do things that are not the norm, but instead do things that are not expected by Black women. I teach at an all girls school, so it is important that I share these women with my students.

Help students learn the cultural pulse of a time period through music.

As an English teacher, I can link periodic music to political and social movements alluded to in our literature.

I will be doing more research on Black female musicians for our jazz unit this year!

I hope to be more interdisciplinary and help students practice listening with historical musical selections.

Find ways to incorporate music more regularly in the classroom.

I will expand on the idea of music as community building in a social-emotional unit. I will also be intentional in teaching music history and connecting it to Black history.

I will share these resources with other teachers to enrich and enhance their lessons.

My 7th grade and I will be doing a unit on the Harlem Renaissance, but I am thinking I could go a bit further back in time, and maybe have the students study the historical contexts.

Sharing with students the power of music and how it has been used as a form of resistance.

Presenters

Guthrie P. Ramsey Jr. is a music historian, pianist, composer, a Professor Emeritus of Music at the University of Pennsylvania. A widely-published writer, he’s the author, co-author, or editor of four music history books and many essays and articles, including Who Hears Here? On Black Music, Pasts and Present. As a producer, label head, and leader of the band Dr. Guy’s Musiqology, Ramsey has released five recording projects and has performed at venues worldwide. Ramsey hosted the Musiqology Podcast, and Musiqology Rx is his community arts initiative that provides quality arts programming to under-served communities. He has written for and consulted with museums and galleries, and was co-curator of Ain’t Nothing Like the Real Thing: How the Apollo Theater Shaped American Entertainment for the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing, and on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project. He is also a blues musician; his band is The Blue Tide.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn