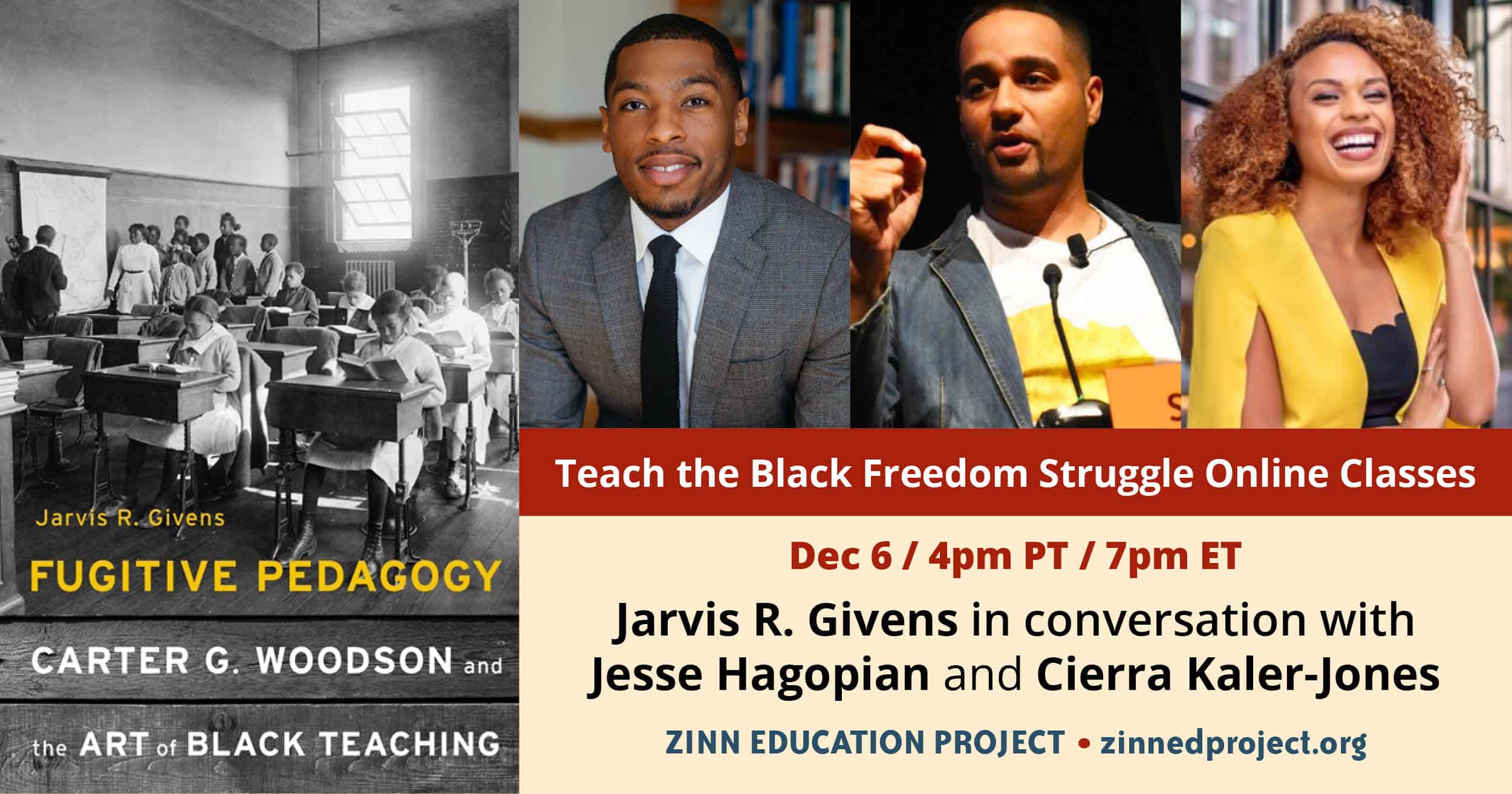

On December 6, we hosted Jarvis Givens, author of Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching, in conversation with Jesse Hagopian and Cierra Kaler-Jones. Givens’ work details the long assault on Black education that occurred from the period of enslavement through the life of one of the founders of the Black studies tradition, Carter G. Woodson.

Here are a few reactions from the participants:

Tonight was a pleasure. The depth and breadth of knowledge that Dr. Givens as well as Jesse Hagopian and Cierra Kaler-Jones had was impressive and inspiring. Thank you!

I learned so much. I think that Tessie McGee’s story really influenced me to look more into it. And the fact that people were being fired for teaching the truth. We must teach the truth.

The ideas were so powerful! That everyone had a teacher, everyone who we associate with movements had a teacher somewhere. And the love for teachers! So powerful!

I love this. I feel like this will help me to solidify my understanding of the loss of historical truth by our society because they have shut out BIPOC communities. Thank you.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion. Jesse Hagopian: We are very lucky tonight to start this conversation with Dr. Jarvis Givens, assistant professor of Education and African and African American Studies at Harvard University, and the author of one of my favorite books, Fugitive Pedagogy. He runs the Black Teacher Archive in partnership with another one of our favorite professors, Imani Perry. So thank you for being with us here today, Dr. Givens. Jarvis Givens: It’s my pleasure. Thanks for having me. Hagopian: No doubt. I’m going to turn it over to Cierra to start off the conversation. Cierra Kaler-Jones: Thanks, Jessie, let’s kick it off. We are just so excited and want to first start by offering some more roses to you, Dr. Givens, for this incredible history, but also the ways in which you see your knowledge and use this history and share it in so many ways, shapes, and forms through public scholarship. So, in addition to your book, Fugitive Pedagogy, you also wrote a very powerful article for the Atlantic about what’s missing from conversations about antiracist teaching. You write, and I quote, “We have yet to fully account for the tools African American teachers of the past left behind for us to pick up, reconfigure and do battle with in our time.” So, can you tell us more about what is missing from conversations on antiracist teaching, and what are some of the tools that Black educators have left us? Givens: Well, first of all, thank you for that question. And thanks, again, for being here to be conversation partners with me tonight. I’m super grateful for all the folks that are present on this Monday evening, to engage in this conversation. Many of us are educators, so we’re at the tail end of the semester and I really, really appreciate the fact that folks are willing to engage in this kind of learning, in this community, at this time of year. I appreciate that question because it allows me to talk about the fact that some of the translation work that I’ve been having to do about the book — because I didn’t anticipate that we would be living in a moment where we have these kinds of legislative campaigns to restrict how we teach about race and the history of racial inequality in the context of schools — I wasn’t aware that when I was developing this book, over the course of like ten years, that it would come out at a moment when the language of antiracist teaching would be so popular in public discourse. But, that’s what happened, the book came out at a moment when the language of antiracism has been taken up in ways that are opening up important conversations. But then other times, I felt like there was some superficial engagement with that idea, and particularly a lot of ahistorical conversations that I felt did a disservice to all folks involved who are actually trying to engage in meaningful work when we are reproducing the kinds of erasure of Black educators that have always been engaging in the work of challenging racism in the context of schools because that was a part of their political project as educators from the jump really. So for me, one of the key things that was missing from the language of antiracist teaching was a meaningful engagement with a very long history of Black teachers, working as intellectuals and political organizers as a part of their professional roles, and particularly over the course of the long Black Freedom Struggle. There’s no way for us to make sense of the long history of Black folks engaging in antiracist struggle without thinking about the central role that Black teachers played in that process. So, I was trying to introduce the book in the current moment, to say that this is actually a story where I’m talking about Carter G. Woodson and this world of teachers that he was a part of, that helps us think in more rigorous ways about what we’re actually engaging in when we’re trying to name the dynamics of race and power in the context of schools, both as it pertains to curriculum, but also as it pertains to other kinds of structural dynamics in schools that limit how folks can actually engage in this work. We have the legacy of Black teachers to look to to see how they have been working to navigate that experience, before the 20th century, but absolutely up and through the Jim Crow era. So, that’s one of the things that I felt that was missing. Especially, Jesse mentioned the project that I have taken up with Imani Perry, and that is working to uncover and preserve the records of Colored Teachers Associations, which were these important institutional bases that Black teachers created that allowed them to do the kind of advocacy work that they weren’t able to always do individually in their classrooms but that they were able to do as a professional group because of the fact that they were organized, and a networked body of educators, both striving to teach students based on their content areas, but also understanding that there was a political project that always exceeded any particular area of study — whether it be a math teacher or a history teacher or an English teacher — there was a political clarity about the work of what education was supposed to be doing, and the lives of the students and communities that they served, and that political clarity informed how they moved, the organizations and institutions they built, and the curriculum struggles that they engaged in over the course of generations. Kaler-Jones: Yes, I just appreciate you engaging in the historical context. I know from previous conversations that Jesse and I have had with other Black educators that your work reminds us to lean into historical memory, that there is resistance in our DNA, and we see ourselves as part of a long historical continuum. So, thank you. Hagopian: Yeah, and I love the way you just stated the fact that we can’t understand antiracist pedagogy without understanding Black teachers. It seems obvious, and yet people haven’t dug into that. Then also the way we can’t understand the Black Freedom Movement without understanding Black teachers — like Martin Luther King had a teacher, Rosa Parks had a teacher — and so many of these figures had teachers that influenced them. Givens: We’re taught to think of these folks as though they just grew out of nowhere, and that they had these kind of visions of justice. Perhaps sometimes we’ll think about the role of the Black church in the development of many of these leaders, but post-Emancipation Black teachers were just as central in terms of the first cohorts of leaders of the free people. And that continued to be the case up and through the Jim Crow era. Black teachers were one of the largest groups of Black professionals that really helped sustain so many of the organizations and institutions that were important meeting grounds for shaping this kind of counter public sphere for Black organizing. And it’s important that we think about that. But, absolutely, folks like John Lewis, Martin Luther King Jr., Angela Davis, these folks actually write very explicitly about how formative their educational experiences were in the context of Jim Crow schools under the tutelage and leadership of Black educators. bell hooks, before the language of antiracism became super popular in the contemporary moment, bell hooks is writing in 1992 and she says in Teaching to Transgress, “For Black folks, teaching up, education was always political because it was rooted in antiracist struggle.” That’s a direct quote from Teaching to Transgress. When she’s writing about that, she immediately starts to talk about her Black teachers at the Booker T. Washington school in Hopkinsville, Kentucky. She’s talking about the Black teacher she had before she went and desegregated one of the local high schools. So we have all of these important intellectuals, all of these important scholars and political figures, who have actually identified the important role that Black teachers played. But for whatever reason we’ve become this narrative about Black education prior to Brown being a story of separate and unequal, and nothing else has really dominated the way that we tell that story, in the way that we recall the past, even though we have all of this evidence. Anywhere that we look, to suggest that the story of material neglect, lack of resources, dilapidated school buildings, that’s part of the story — but that cannot be taken up as a totalizing narrative, right? It’s very important cultural, political, and intellectual work that has always been done in the context of Black schools and in Black communities with teachers and students. It’s important for us to be able to think at the intersection of those things and to think across those tensions. Hagopian: Yeah, what a powerful reframe for looking at Jim Crow schools. I think that’s going to lead to a lot more questions. But I wanted to follow up by just saying that your concept of fugitive pedagogy as a lens for analyzing schooling and the struggle for antiracist education, to me, was like a key unlocking the truth, especially in light of all these bills that have been passing to ban the teaching of structural racism. In Fugitive Pedagogy, you wrote, quote, “Black education was a fugitive project from its inception, outlawed and defined as a criminal act regarding the slave population in the southern states, and at times to an object of suspicion and violent resistance in the north.” So, I was hoping you could talk about the concept of fugitive pedagogy more, and some of the many ways and times that Black education has come under attack. Givens: Thanks for that question, and for engaging with the text directly as well. I appreciate that. The idea of Fugitive Pedagogy came to me, as I was writing this and I was trying to make sense of how do I name a relationship that was very clear to me in my mind, between the subversive work that Black teachers were doing in the context of Jim Crow. So the book opens with the story of Tessie McGee, who was a teacher in Webster Parish, Louisiana, and she’s secretly reading from a Carter G. Woodson textbook in the 1932 school year. We only know that this happened because one of her former students — and I appreciate you talking about your former high school teacher and the things that you likely remember from things that she did and the class that you had — but I’m able to access the narrative of Tessie McGee because of one of her former students recalling what she did at the Webster Parish Training School and secretly reading from Carter G. Woodson’s textbook. And if people came into her classroom, she would begin reading from the required curriculum. Then he says, when the door closed, her eyes went back to the book in her lap. I know that we are doing similar things today, but it’s really, really important for us to take seriously the violence of Jim Crow and why that level of vigilance was so important for Black teachers who were fired for doing much less during this period. So it’s really important to take seriously the violent surveillance that structured the experiences of Black people during Jim Crow. But why that story was important for me was because that was a moment where I got a glimpse of how Black teachers navigated power in real time. In a sense, that kind of an instructional move, if you will, was about more than just that one moment, but about the political clarity that this teacher had, likely that the students also understood and also had, because they understood what the teacher was negotiating in that context. But that’s also part of a much longer and expansive set of Black educational politics that I wanted to name. So when I was reading that, for me, in my mind, there was a clear relationship between that story and the story of people climbing into pits in the woods in the middle of the night during the period of enslavement to learn to read and write. Or the story of Bill Parker, who was an enslaved boy in Virginia in the antebellum period, who recalled how he would keep a copy of the Blue Back Webster Speller on his head concealed underneath a hat. With that he would travel and go to find someplace to actually try to learn and to teach himself how to read and write. There was a very clear relationship between those things to me, and I wanted to talk about that. The language of fugitive pedagogy helped me draw a narrative line from the way that Black folks during the period of enslavement worked to subvert the restrictions imposed on their lives. We know things like anti-literacy laws existed during the period of enslavement. The first anti-literacy law was passed in 1740 in South Carolina, in response to a slave revolt. In responding to the Stono Rebellion in 1739, they created this comprehensive slave code. One of the things that’s included to enforce the surveillance of enslaved people is that literacy becomes criminalized, because it was believed that the enslaved people that organized this revolt might have used the written word to coordinate their rebellion. That long narrative of criminalizing Black education — and where we see these laws proliferating, leading up to the Civil War — created a structural dynamic where Black education is criminalized, and where Black people are having to navigate these constraints in order to seek out meaningful learning and meaningful education. Even before that Stono Rebellion, I was just writing recently about a slave revolt in New York in response to the slave revolt that happened in 1712. In New York, it’s believed that a Black school might have helped to incite this rebellion, so this school became the target of violence, and it became this effort to censor and restrict Black people’s access to literacy, even in the context of New York. We have plenty of these cases across regional boundaries, so it’s not just the southern narrative. What I’m writing about in terms of the restrictions imposed on Black education during slavery and post-Emancipation was a part of the national culture. And Black people — even after it became legal, technically, for them to engage in learning freely after the Civil War — there continued to be violence that they met. Between 1866 and 1876, more than 600 Black schools were burned down in the South. This suggests that even as Black education becomes legal — in the period where Tessie McGee will be educated — there was still violent restriction. So Black people continued to have to pursue meaningful parts of their education in secret. That’s what the language of fugitive pedagogy is trying to get at, to say that there’s this narrative line that we have to make sure that we hold up that takes seriously the criminalization and the persecution of Black education, but also the constant straining against that confinement. And fugitive pedagogy is a language that helps us understand that. It’s rooted in the story and the legacy of fugitive slaves and fugitive literacy practices during enslavement. The language of fugitive pedagogy in that era reminds us that the basis of a Black educational tradition, in the context of the new world or the Americas, emerges from those enslaved people who were stealing away to pursue literacy. The very first literature of Black people, that is the basis of a Black educational tradition, are the freedom narratives of fugitive slaves who ran away. The language of fugitive pedagogy is indexing that longer history and saying that we have to make sure that we understand those educational politics on a continuum. Structural things develop and change, but there are these ways that Black folks are negotiating constraint. And the violent resistance against their education is a consistent narrative. So too is their resistance to that, and it shaped the very nature and the very form that Black education took on. Kaler-Jones: Wow. I’ve been listening and taking notes, and also following in the chat all of the folks that are also with me [in having their] minds blown at this history. To think about the Tessie McGee story that you tell is one of my favorite stories, and I love how you also mentioned the negotiation, and also the disruption, the clear disruption of power, in that particular story. I’m thinking about all of the educators who, in the face of legislative attacks, in the face of having their names printed, and in the face of being fired for teaching the truth about history, are still standing and resisting and saying that we are going to continue because we must teach the truth. I also love that you talked about the slave revolts and the North, that this is national, and the narrative that we often hear in corporate textbooks that it’s in the South, that it’s out there, that it’s not us. This “not us” mentality leads us to continuing to perpetuate it. It makes me think about so many of the other Teaching the Black Freedom Struggle courses: I’m making so many connections in my mind about Jeanne Theoharis talking about Rosa Parks and the work in the north, about the class that we had with Clint Smith and How the Word Is Passed. He talks about slavery in the north, and then Jeanne also talks about how Martin Luther King warned of the northern white liberal. We see this very clear theme in the long Black Freedom Struggle of also making sure that the narrative discusses what is happening in the north, that this is a national effort. I’m moving into my next question. Earlier, you mentioned how all of these figures that we often learn about in Black history were, of course, shaped by teachers. You talk about Carter G. Woodson’s teachers. So, can you share with us the embodiment of fugitive pedagogy in Carter G. Woodson’s life and experiences? Then, for the educators that are part of this class today, what should educators teach about Woodson’s life and legacy? Givens: Yeah, thanks for that question. It became very useful to use Woodson’s life as a lens to explore this kind of meta narrative of Black education as fugitive pedagogy, both because he wrote about it in extreme lucidly in his own textbooks — his first published book was The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861, where he talks explicitly about Black people stealing away to learn. In that first book that he wrote, but also in his textbook that he published for Black students, in his first textbook that was published in 1922, he talks about Black people during the period of slavery, engaging and learning as a means of escape. He talks about this tradition of the escape practices that Black folks engaged in through learning and pursuing meaningful education. But his life, the biographical details of Woodson’s own life, became very useful for me to pick apart. Some of the details that I thought were important. For instance, Woodson is both the child and the student of formerly enslaved people, so he’s a part of this first generation of Black folks born after Emancipation. But one of the things that’s important is that his first teachers are his formerly enslaved uncles, who were not able to learn to read and write openly until they were able to attend the Freedmen Schools in Virginia. But, for me, it also became important to talk about the family history of these teachers. And his own parents became early scripts in Woodson’s own education, more than just the reading, writing, and arithmetic that his first teachers passed on to him. Their own lived history also became very instructive for the lessons that he would take up and enact when he became a teacher himself. The fact that these first teachers of his were his formerly enslaved uncles who are teaching, trying to prepare the next generation to try to imagine a more expansive vision of what freedom could mean, we have to understand that as being contextualized by the very lived history that they themselves had. Woodson talks explicitly about stories that formerly enslaved people passed on to him when he was a child. That will become important armor when he got to a place like Harvard, that told him that Black people had no history, or at least none worthy of respect. For him, having worked with illiterate Civil War veterans in the coal mines — who paid him to read to them in the evenings after work so that they can interact with the written word, so that they can participate in literary culture — and they’re bearing witness to things that they recall from the Civil War. They’re bearing witness to their own lived experiences. So, Woodson has a very firm understanding that these people are also repositories of knowledge, are carriers of history, and that he will continue to draw on that when he pursues his own educational training to become a historian, but also when he becomes a teacher. One other thing that’s important is that Woodson would go on — he started high school at the age of 20 in Huntington, West Virginia, where his first cousin was the principal of the high school. He would witness his cousin be fired from the high school because of the fact that he ran an independent Black newspaper, where he was trying to run an independent slate of Black candidates for local political office. Woodson saw very early on the kind of constraint and surveillance that Black teachers had to navigate. These pieces of Woodson’s life really reflect the broad range of experiences in Black education, from being educated in a one room schoolhouse and his connection to the narrative of enslaved people and their pursuit of education and literacy, to the fact that he becomes a school teacher himself, gets multiple Masters degrees, gets a PhD in history from Harvard while he’s a public school teacher. He’s thinking of these ideas and building these organizations to try to develop a new system of knowledge to serve as a foundation for what a meaningful and liberatory Black education could look and feel like. That’s really what he’s doing, trying to rewrite literally the scripts of knowledge that we see when he founds the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, when he founds these journals, and using his small salary as a teacher in order to do this stuff. He would get to Howard University and be a professor for one year, but he would leave Howard University because, again, this surveillance of the white leadership of Howard University that restricted what Black professors could and could not do there. So his life runs the gamut of Black education, up and through the Jim Crow period. I think that he is the very embodiment of so many of these important things — the rich intellectual tradition, the organizing and the institution building, the subversive efforts and labor to navigate the constraints of education — but also the imagination that Black teachers had to try to create alternative options, alternative curriculum, in order to meet the needs of their students. I think there are all these things that are so central to Woodson’s story. And many people just think of him as the father of Black history because he was a historian. I would say no, we have to emphasize the fact that he was a public school teacher for nearly 30 years. And that was central to so many of the intellectual questions that he asked. And so central to the political project that he took up in building the organization that would create Negro History Week, which we all now celebrate as Black History Month. Black History Month is an outgrowth of the intellectual organizing and the political organizing of Black teachers, and we have to recognize it as such. We rarely ever think of it that way. We just think of Black history. I don’t know how people think of Black History Month these days, to be honest. I’m often confused about how many people celebrate it, but I think that’s a perfect way to think about the centrality of Black teachers to the Black Freedom Struggle. They’re hiding in plain sight, their contributions, and so I think Woodson is a very important figure that helps us reassess the role that Black teachers played and what they’ve gifted us. Hagopian: Yeah, no doubt. Thank you for that. In a few of your answers now you’ve been talking about this concept of intellectual surveillance and I wanted to drill down on that a little bit more, especially because I’m working on a book right now about the teach truth movement that’s pushing back against these anti-CRT laws. I’ve been researching a lot about the McCarthy era recently, and how much intellectual surveillance there was during the anti-communist Red Scare of the 1940s and 50s. But I think this concept is so crucial to understanding Black education, the idea that there’s an acceptable range of knowledge that Black folks have to fall into, and when they go outside of that they’re punished and criminalized. I’m thinking of things like the anti-CRT bills today, but even the way standardized testing is used. I’m hoping you could say more about this idea of intellectual surveillance. Givens: That was central to so much of what Carter G. Woodson was bumping up against. But also, intellectual surveillance has manifested in that story of Tessie McGee as well. The fact that she has a curriculum, that’s the required curriculum that says just one of . . . I was able to go and look at the public school records to get a sense of what the required curriculum Tessie McGee would have been required to teach from, based on Louisiana’s adopted curriculum. Or it was based on a textbook called Modern Times and the Living Past. I’ll share a quick reference just because I have it handy here, but in this required curriculum, what Tessie McGee was supposed to be teaching from, it says, “Not only are almost all the civilized nations of today of the white race, but throughout all the historic ages, this race has taken the lead and has been foremost in the world’s progress.” The author then goes on to say, “Almost the entire book will be devoted to the doings of the caucasian race, or at least nine tenths of the book must be given to an account of the Indo-European branch of the race, as the Indo-Europeans have dominated the world for the past 2,500 years.” So, the intellectual surveillance and curricular violence is deeply embedded in the curricular foundations of the American school, and the fact that these teachers were required to teach this information as a part of that narrative. So the story of intellectual surveillance is central to the story of Tessie McGee, and to make sense of that narrative. But also, it becomes very important when we start to talk about capital and funding, white capital in particular. White northern corporate elites who are funding educational development and intellectual scholarship by Black scholars. Oftentimes we have this very complex dance between people like Woodson, people like Du Bois, people like Zora Neale Hurston, who are having to negotiate white funders deciding what’s worthy of being funded and what is not worthy of being funded. And this is something that is a struggle for Carter G. Woodson very early on because he was very vocal about some of the aspects of white paternalism that he felt undermined the work of Black teachers and Black education. By the 1930s, Woodson wouldn’t be able to attract any support from any major white philanthropist by that point because of the fact that he was very outspoken against a number of things. For instance, some of their efforts to control missionary education in Sub-Saharan Africa, their efforts to block certain African Americans from going to places like South Africa, for instance, is a story about a teacher named Max Yergan, who was blocked by a group of white philanthropists from going to work for the YMCA because they felt that he would radicalize the natives. Woodson was very public in his critiques of these philanthropists. Then you have a situation, for instance, in 1932, where the Phelps-Stokes Fund, they get together a group of scholars and they say, “We want to create this encyclopedia on the Negro. But on one condition, W. E. B. Du Bois and Carter G. Woodson cannot be a part of it.” So they get together these groups of scholars, and all the Black scholars that came, they said, “Wait, we can’t do an encyclopedia on the Negro and not have the first and second Black PhDs in history that are alive, and leaders in the field, would not be a part of it.” So then they say, “Okay, well then we’ll invite them.” So then they extended the invitation to Woodson and Du Bois. Du Bois accepts the invitation; Woodson refuses because their intentions are very clear, based on these kinds of restrictions that they impose to begin with. So that negotiation about the role of private capital and dictating the intellectual work, the development of Black education, this is a part of what people think of as the Du Bois – Washington debate. I always say, that’s actually a problem, we need to stop saying that this is Du Bois and Washington, when in reality it’s white philanthropists facilitating this dysfunction that gives individual people like Booker T. Washington an outsized influence over what should and should not be the direction that Black education goes. Using these people as a figurehead when, in reality, it’s really about the people who are pulling the purse strings. This story about race and private capital and the manipulation and under-development of Black education, that’s a part of this. And Woodson is very vocal about it, about what white publishers won’t print. Which is why you see the people creating these institutions to publish their scholarship, because they can’t get published in mainstream academic journals. Zora Neale Hurston also has an article called “What White Publishers Won’t Print”. This is a very big conversation, this idea of intellectual surveillance, and then when you add the anti-communism part in there. There’s a scholar named Charisse Burden-Stelly who’s doing excellent work looking at the intersection of anti-Blackness and anti-communism, and the ways that people — even Woodson, who is pegged as radical and potentially communist leaning, even if they publicly say that they’re not — there’s a way in which radical critiques from a Black context are oftentimes automatically read as having these communist leanings. There’s an intimacy between anti-communism and the suppression of Black intellectuals during that time period. That’s really important to tease out, and that’s the scholarship I just mentioned. Charisse Burden-Stelly is a person who’s doing excellent work uncovering that. Hagopian: That would be so useful for me. Thank you for that. It also just makes me think about the way Bill Gates has entered education today and funded the Common Core as another kind of modern example of white philanthropy engaged in intellectual surveillance. But, thank you for that history. Kaler-Jones: Yes. Oh, my gosh, wow. I’m sitting with all of that and just thinking about how philanthropy is a made up sector, and in that, how funding and just like you said, Dr. Givens, that capital contributes so deeply to what is allowed to be published and the policing infrastructure, so not only thinking about intellectual policing, but the intersections with physical policing, with emotional policing, psychological policing, and how all of these in totality lead to young Black and brown folks growing up and experiencing curriculum that in Stephanie Jones’s words is “violent” and Bettina Love’s words is “spirit murdering.” Who they are and how they show up in the world by not actually having their communities represented accurately and authentically. Oh yes, the slides. Givens: There’s one slide, really quickly, because when you mentioned it I was thinking this is like another example. So, this is a newspaper clipping from Muskogee, Oklahoma in 1925 when the local white school board, which was heavily influenced by the Ku Klux Klan. There’s this collusion between the local Klan chapter and the white school board here in Muskogee, Oklahoma. But they learned that Carter G. Woodson’s textbook is being used in the local Black high school, and they confiscate the textbooks, they reprimand the teachers. A Black man, who was the principal of the school, was threatened and forced to resign. So this question about what does intellectual surveillance look like? These are the kinds of cases we have. Other examples of people, someone like John W. Davidson in Georgia. He’s not fired for teaching African American history, he’s fired because he’s insisting on teaching Latin at the school that he created. Latin, a classical liberal arts model of education, was seen as an educational model that was inconsistent with white philanthropists. You have folks like George Peabody and the Rockefellers who were part of the board and essentially fired him from a school that he founded because he’s not abiding by the industrial model of education, because he seems to be teaching this liberal arts model of education. This idea of the intellectual surveillance that these teachers were operating under, it’s about teaching about race and history, but it’s really a conversation about control and the ideological orientation of how Black people are expected to fit into the social order. In this instance, it has to do with them being an exploitable group of laborers in the agricultural south, which is why you have that kind of tug of war. William Watkins’s book, The White Architects of Black Education, is a foundational text to think about the relationship between white funders and the manipulation of Black education up and through the first few decades of the 20th century, where you have these private white philanthropists and industrial capitalists who have near unchecked control over the direction that Black education would take through an education board they create in the South in the first decade of the 20th century. So, by World War I, they had near complete control over the direction that Black education could take, structurally. We know that Black folks were doing different things on the ground, but the structural dynamics has to do with that story of private white capital manipulating the development of Black education. Then we have Black folks like Tessie McGee, like Du Bois, like these teachers that I just shared, who are trying to negotiate those structural constraints in the context of Jim Crow schools. Kaler-Jones: Wow. It’s making me think, too, about the McGraw Hill textbook that has the image of what is now the United States, and it calls enslaved people “workers.” Just to pull that thread to the present day, I’m seeing in the chat box many people commenting that this is happening in Texas, this is happening in this state, this is happening in this state. There are actually states that are not only banning critical conversations about racism and oppression, but are also saying that young people, students cannot get credit for engaging in advocacy, engaging in lobbying, engaging in organizing. It said that that is not allowed to be part of the curriculum, either. We see, also, as you’re mentioning, that policing of not only the content but also the action, those actionable pieces. As we’re talking about textbooks, I have one last question before we move into breakout rooms. You discuss this — and this just blows my mind and fills me with so much joy and wonder — you discuss how the first textbooks written by Black Americans were authored by fugitive enslaved people. You also write that every textbook written by Black school teachers between the late 19th century and Woodson’s first textbook in 1922 included expansive coverage of maroons, fugitive slaves, and slave insurrections. So, can you talk about the textbooks that fugitive enslaved people and Black educators created? And these texts centered resistance, so could you share some more of the stories they uplift that we would not see in white-centric textbooks? Givens: Thank you for that question. I should say, that part didn’t actually click in my mind until I was in the second round of revisions for the books — I shared it with a friend, because the first Black authored textbooks were actually written literally by fugitive slaves. This was when I was trying to justify why I’m relying on this language of fugitive pedagogy. And she was like, “Wait a minute, is that in the book, the fact that the first Black authored textbooks were written by fugitive slaves?” I was like, “No, it’s not in the book because I’m focusing on the textbooks by Black teachers,” and she was like, “No, I think that you need to help people to understand and make that connection in terms of why the language that you’re offering helps us to hold in place, and to recall, this kind of intellectual lineage and this political heritage at the center of Black education that you’re trying to name.” But, you know, James W. C. Pennington was an escaped slave from Maryland who learned to read and write while he was a fugitive slave, and he would go on to write a textbook. A textbook on the origins and history of the colored people that he wrote in 1841. Then William Wells Brown also wrote a textbook in the 1860s. And these folks, I should say, also wrote some version of a slave narrative as well, where resistance and their pursuit of freedom is also a central part of the narrative. So, of course, that script of resistance is central to the narrative that they’re trying to create about what it means to take Black life seriously in the context of the modern world. James W. C. Pennington, he comes up, he offers this idea of the chattel principle, he talks about the chattel principle, which is essentially the fundamental idea that shapes contracts and the fact that you can have property in a person. He’s saying, actually, that that very fundamental concept is central to the dehumanization of Black people. It’s not the spectacular scenes of violence of Black people being whipped at the whipping post, it’s what he calls the chattel principle that actually justified and legitimized these kinds of violence that were imposed on Black bodies. This is a fugitive slave literally theorizing different ways of understanding and knowing his condition as a fugitive slave, as someone who’s deemed property. So, it was very important for me to hold this in place. This intellectual work is very much so bound up in the struggles that fugitive slaves and Black folks writing during the period of slavery are trying to make sense of. But then, even after that, when we get to the textbooks by people like Leila Amos Pendleton in 1912, or Edward Johnson in 1890, or Carter G. Woodson in 1922, or John Cromwell in 1916, their textbooks are filled with these kinds of narratives. These are just some images taken from Carter G. Woodson’s book, where we see the Haitian Revolution and Toussaint Louverture being a very important and prominent figure. Even though these are supposed to be textbooks about the Negro in the context of the United States history, but we see them drawing on the Haitian Revolution as not the only example. They’re writing about maroon communities in Suriname, in Jamaica, and Woodson’ textbook, and also Leila Pendleton’s, they’re talking about quilombos in Brazil. It’s kind of this diasporic consciousness that’s informing the way that they’re conceptualizing Black history. And it’s fundamentally a history of resistance that we see through these images, but also through the narratives. So again, this is why the language of fugitive pedagogy and the archetype of the fugitive slave became so important. Because it seems to me that the fugitive slave started to become this cultural symbol, this folk hero, in the curriculum that Black teachers developed, in the way that they appeared again and again in these texts, in their annual celebrations of Negro History Week, and all these sorts of things. So, the language is trying to hold in place that story of resistance, that’s tucked in Black teachers’ curricular imaginations, because it’s a core part of the political project that’s at the heart of Black education, and it’s a part of the origin story of Black education as well. Kaler-Jones: Now that we are back from the break and folks have had an opportunity to just be in conversation and to engage with one another, Dr. Givens, what would you like educators to know and to teach about the history of Black education? Givens: Thanks for that question. Certainly, I think that a lot of corrective work needs to be done in terms of how we reframe that Du Bois – Washington narrative that I think we hear all the time. I felt when I was first writing this book, when I was just thinking about Woodson, before I even got to the stuff about fugitive pedagogy, but I was just thinking about Woodson and his textbooks, even among academics and scholars and people who are historians of education, I kept getting questions about whether or not Woodson was more of a Washingtonian or more of a Du Bois type of educational philosopher, or educational practitioner. For a number of years, I was trying to figure out how to answer that question because I received that question so often. But then I realized that that binary kind of framing is actually a flawed way of thinking about the range of Black intellectual thought when it comes to education in general, especially when we know the fact that there was never this kind of rigid binary, even in Du Bois’s own thinking. Even folks like Du Bois and other scholars recognized the importance of practical education, but they were challenging the idea that there should be any single model of education just for Black people because they recognized the way that industrial education was being used to exploit Black people as a vulnerable group of laborers in the post-Emancipation period, where they’re still being exploited in the context of the South. Then we think about the labor dynamics under the agricultural economy there. So, I would say that that’s absolutely one of the important things to reframe. I would also say that we have to be intentional to think against the grain of the narrative that grows out of the litigation strategy of the lawyers in the courtroom for Brown v. Board. We’ve taken a litigation strategy and used it as a totalizing narrative of what Black education was prior to Brown v. Board and the promise of Brown and desegregation. It is a very narrow perspective about what constituted Black education prior to Brown, and we do ourselves a disservice, and students that we’re teaching a disservice, by not thinking beyond that, and saying that the story of Black education is not just a story of separate and unequal. It’s not saying that desegregation of Brown was not an important piece of legislation. We have to be more nuanced and more nimble in our thinking to be able to contend with both the consequences of Brown that were not the intended consequences of the Black folks that advocated for it. But there were consequences, there were costs associated with the way that desegregation was rolled out, there were things that were lost, that were undermined, that we need to be able to wrestle with. Even as we can take seriously the significance and the importance of Brown, we also have to be able, on the other side of that, to take seriously the very rich political and cultural history that was so central to the story of Black education. And we have to be able to talk about both of those things: We have to be able to talk about the persecution and the resistance, and it’s not one or the other. The realities of Black life have always been lived in that particular tension. There are all sorts of narratives, beautiful narratives that we should also be thinking about, and taking up and thinking with as well as not just the story of Black students being shouted at while they’re trying to desegregate Central High School in Little Rock. There are all sorts of other important and beautiful narratives that we also need to engage with to expand how we think about the heritage of Black education. This is one of the reasons why, in some ways, I understand why the language of antiracist teaching is important. But the reason that I personally find the language to be limiting is because it is a kind of negation, it’s a vision of education that’s about refusing something. And I think that when we take that as the total frame of what a liberatory educational model is, there has to be some kind of positive project. Black education has not only been about responding to whiteness and white supremacy. Black people have also done work to bring students into the classroom and to try and shut out the world around them and also engage in things that are not about responding to external influences. I think that the language of anti anything is one that’s rooted in negation. There has to be a positive project for us to be thinking about what constitutes liberatory education, and I think that these Black teachers, they were doing that, they were both having to engage in the resistance, but they were also doing things that had to do with trying to imagine and to partner with student to engage in the process of imagining things that did not exist in their immediate surroundings. I think that it’s important for us to reclaim that and to think about that, which is why I love these stories of enslaved people stealing away into the woods and pursuing something that’s not about just responding to the violent external realities around them, but pursuing something else and working to enact something that you see as a higher vision of what it means to be human right, and to imagine new ways of being in relationship with one another, that, I think, is important for us to think about. That’s kind of all over the place. But I just think that there’s so many wonderful stories and so much rich history when it comes to Black education, and we have a very impoverished perspective in terms of how we remember the Black educational paths. It’s unfortunate because I think that it’s inspiring for students to learn about this history, it’s inspiring for teachers to learn about this history, because it allows you to say this is a different standard of what it means to be a teacher. This is a different way for me to lean into my vocation of what it means to be an educator that’s set apart from the technocratic approaches to teaching and the current state of education where all teachers are constantly being, de-professionalized and alienated from their work, and especially educators of color. All teachers to be honest, especially educators of color. We have this very rich history for all teachers to look at and see and say, “This is a body of educators who recognize the way that these structures undermine what their work actually was and decided to set their own professional standards about what constitutes meaningful teaching, and what constitutes liberatory education.” That’s something that’s important for the professional development of teachers. The same way that students need counter-narratives to think about themselves and their identities, teachers also need counter-narratives to think about their work, their professional identity, their own vocation. And teacher training programs do a terrible job of allowing teachers to think about situating themselves in an educational tradition that’s not just about compliance to the current protocols and standards. But I would say that the history of Black teachers really allows us to tap into a different model of teaching that has implications for all folks. I think it’s particular to the African American experience, but it’s a universal story about educators leaning into the higher vocations of what it means to be a teacher and what it means to teach against the grain, to teach against structures of power that all educators have to confront at some point. Hagopian: Yeah, no doubt. That’s why I’m so glad we had like over two hundred educators here tonight, hearing this history, thinking about how to implement it today. We’ve got a question from Renee Moore, who said, “You write in the book about how Black teachers created a porous relationship between scholars in higher education and K–12.” And then she says, “Could you talk more about that aspect of teachers’ work and Dr. Woodson’s role in that?” Givens: Yeah. Thank you. So, that was Renee that asked that question? That’s a good question, I appreciate that. I don’t know if that was in chapter five or in the conclusion, but some version of that statement shows up in both of those places. I was so fascinated to see the boundaries collapse between scholars in higher education and Black educators in K through 12 settings because we see, for instance, Woodson is a leading intellectual of his time and was primarily a school teacher for the majority of his professional career as an educator. We see teachers and the “Black intellectual elite” engaging in academic and intellectual struggle, and as a part of their professional work. We see study groups being formed among teachers in these colored teacher associations. There’s an example, I think I ended up having to take it out of the book, but in 1934 there’s a moment when W. E. B. Du Bois is addressing a group of teachers in New Orleans, for the New Orleans Colored Teachers Association, and he writes Black Reconstruction, and I see that on your shelf behind you, Jesse, I believe. I know that book anywhere, but that book was published in 1935. There’s a meeting in a gymnasium in New Orleans, where W. E. B. Du Bois is talking to a group of teachers for Negro History Week, and he’s talking about this book that he’s working on, about to publish, and he’s talking about the politics of the fugitive slaves that paved the way for the past that will be enacted during the Reconstruction period. You see these teachers engaging in conversation with him in this space where he’s talking about the seminal text that will come out. Then we would see something like the following year in November, when Woodson is coming into town to meet with the delegate of teachers, they’re talking about how they’re preparing this new unit on Black leaders during Reconstruction, during this year that they’re going to implement in their schools. They’re going to have a Mardi Gras float around the Negro and Reconstruction. Then the following year, you see a teacher training school called the Linda C. Jones School, where, after the book is published, a pre-service teacher writes a review of Black Reconstruction after it comes out and publishes it in their magazine for this normal school in New Orleans where teachers are being trained to become educators in the local Black schools. So, just for me to be able to trace that idea and the circulation of it around this important text, but to also see these teachers engaging in this very vibrant, intellectual community was so important for me, because what it suggested is that what we have today, when we think about Black Studies, African American Studies, Africana Studies, whichever name of our particular kind of brand, we only have that tradition because it passed through Black teachers. Black teachers sustained that intellectual tradition and their teacher organizations. Many of the foundational texts that will be reclaimed in the late 1960s, in the 1970s, were either written by Black teachers or were written by scholars who were trained by Black teachers. Many of the students demanding Black studies were the former students of Black educators during the Jim Crow period. So in order to even make sense of the intellect, the academic enterprise of Black studies that became formalized in the American university, we have to think about this much longer rich history about the intellectual work that was sustained by Black teachers. That porous relationship is something that I saw in the historical record that I think raises a set of questions about the rigid boundaries that currently exist between scholars in higher education and teachers in the K through 12 schools. Also the fact that K through 12 teachers are rarely thought of as intellectuals, right? The language of the practitioner, I think, is a limiting language, which is why I write in the book about these teachers as scholars of the practice, because we so often just think about teachers as doers and not thinkers, and we don’t think about pedagogy as an intellectual exercise. Knowledge is being created through the pedagogical process, and teachers’ work is always fundamentally an intellectual task. I don’t necessarily know that that aspect of what it means to be a teacher is really celebrated or encouraged and developed when we think about the kinds of professional development seminars, or even what’s privileged in the context of formal teacher training programs. Kaler-Jones: Scholars of the practice, we’re going to have to lift that up just one more time, because that is such a moving way to think about moving beyond the silos or the hierarchies of knowledge, right? It makes me think about what you were talking about earlier, in the policing of knowledge or in that intellectual surveillance, by not saying that educators have a body of knowledge and expertise is another way that this policing shows up again and again. So, we have another audience question here from Pamela Jones. Pamela says, “Dr. Givens, how do you or would you relate to Dr. Tina Campt’s framing of fugitivity as a quotidian practice of refusal to the Black teacher moves documented in your work? I see their subversion and pursuits as powerful examples of creative practices of refusal?” “And thank you for your work” is what Pamela wants to tell you, as well. Givens: Yeah, thank you for that question about Tina Campt’s work, where she’s theorizing fugitivity. But that politics of refusal is what we see Tessie McGee refusing the required curriculum and refusing to concede the fact that the work that’s before her has to be only in alignment with the required scripts that she’s offered, when she understands that very script as being a part of that very set of curriculum as being central to the very structures of knowledge and systems of schooling that are hostile to her very existence, the existence of our students, or to borrow language from Sylvia Wynter, this is Tessie McGee refusing a curriculum that narratively condemns Black life. That politics of refusal is embedded in James W. C. Pennington refusing the chattel principle and stealing his body and stealing his mind. The pursuit of literacy is about the refusal of the chattel principle as James W. C. Pennington writes about it in saying that they are thinking, feeling, rational beings and Black folks’ pursuit of literacy is not just literacy for the purposes of reading the Bible or writing a pass, but it also is about insisting that they are fully human, that they have an interior life too that they’re not just, to borrow from Frederick Douglass’s phrase when he says that “they were expected to be hands without a head.” So, insisting that they were not just hands without a head, but that they were thinking, rational beings, which, fundamentally, those who are trying to oppose slavery insisted that they did not have these things. That politics of refusal is fundamental to the language of futility. I would say Tina Campt is a part of a tradition of Black studies scholars who writes about this, as early as Nate Mackey in the early 1990s. He’s writing about Zora Neale Hurston’s scholarship, but this is really one of the early theorizations of fugitivity, it is in his essay called “From Noun to Verb.” He’s writing about the folklore and these folk heroes in Zora Neale Hurston’s literature where we see the briar rabbit narratives and the Hi John the Conqueror narratives, these Black folklores that are about resistance and Black people refusing the white gaze and refusing restrictions imposed on their lives. Zora Neale Hurston has a quote, she says, “The white man might read my writing, but he can’t read my mind.” That’s from Zora Neale Hurston. But then you also have enslaved people saying things like “Got one mind for me, another for the master to see.” The language of fugitivity is about this politics of subversion, that and the way that Black folks are navigating power in their cultural practices and their political practices. Tina Campt is writing and taking up that language and theorizing it in her own work. But, a number of Black scholars — whether they use the language of fugitivity or not — have been writing about that for a very long period of time, Carter G. Woodson included. The fugitive slaves that publish these textbooks are part of that fugitive tradition of Black life. Hagopian: Yeah, that reminds me of a poem that we have in our book Teaching for Black Lives by M. K. Asante called ‘Two Sets of Notes’. I don’t know if you’ve seen that poem, but you’ll love it, about how you’ve got to take one set of notes to pass the test, and then the other set of notes, that’s the truth. What an amazing evening we’ve had. If you don’t yet have this book, you have to go out and buy it. Clearly, you need this book. And you’ve got to dig into it and do study groups with folks at your school, and figure out how to bring this in. To help facilitate that process, Cierra and I are going to be doing another workshop with educators to think about how we create activities, lesson plans, and pedagogy around some of the main concepts in this book. We hope to develop lessons that eventually get up on the Zinn Education Project website so people can learn about the role of Black teachers in the Black Freedom Movement and in shaping pedagogy throughout history. So, thank you for that inspiration and for sharing the documents that will be the primary sources, and for everything this evening. We, unfortunately, are out of time. We have so many other great questions that came in tonight that we can’t get to this evening, but folks should come back to our next session about creating curriculum around this book. So thank you very much, Jarvis. Givens: Thanks for the excellent questions and for inviting me to join this beautiful space. Kaler-Jones: As we close, Jesse and I wanted to share one of our favorite quotes from the book. This is one of the quotes that we could not stop talking about. We both highlighted the same passage in the book. You say, Dr. Givens and I quote, “For so long, Black teachers carried the tradition of Black study forward. Along with preachers, they were the dream keepers and the first leaders of freed people. Their teaching conjured a world that has never been yet, and yet must be.” While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Transcript

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms, as well as an audiogram from the session below.

Resources

Here are many of the lessons, books, articles, videos, and more recommended by the presenters and also by participants.

Lessons and Curricula

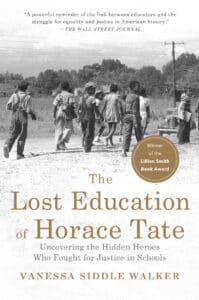

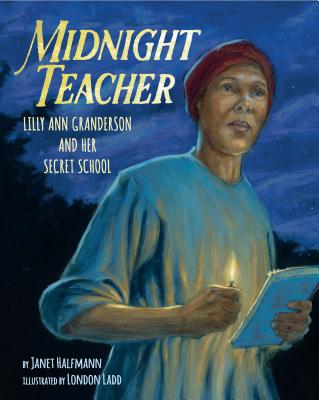

|

|

“A School Year Like No Other”: Eyes on the Prize: “Fighting Back: 1957-1962” Teaching Activity by Bill Bigelow, Rethinking Schools Perspectives on School Segregation Reading, Writing, and Rising Up: Teaching About Social Justice and the Power of the Written Word Teaching Guide by Linda Christensen, Rethinking Schools Stepping into Selma: Voting Rights History and Legacy Today Teaching Activity by Teaching for Change Teaching for Black Lives Teaching Guide, edited by Dyan Watson, Jesse Hagopian, Wayne Au. Discussion Guide created by Cierra Kaler-Jones and Jesse Hagopian The Fight for Educational Equity What Is Fugitive Pedagogy? by Elizabeth Moore and Dan Krutka |

Related Books and Articles

Videos

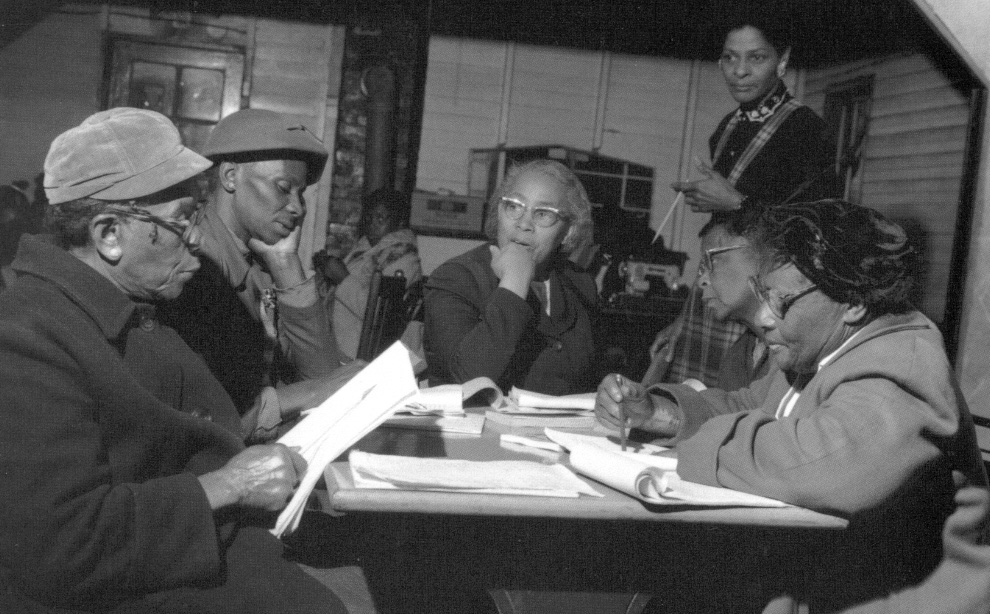

|

National Education Association and American Teachers Association |

This Day In History

Participant Reflections

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

The TRUE impact that Dr. Carter G. Woodson had on education!!!

Fugitive Pedagogy was a new term for me today. It was nice to hear from Dr. Givens about what it means and then apply it to what I’ve learned, or perhaps have not learned, throughout my education. These are topics and ideas that deserve attention in the classroom.

The story of McGee needing to switch between the prescribed curriculum and what needed to be taught.

The specifics about history that allows me to understand today. The role of fugitive slaves in curriculum. Thanks also for the mention of the “communism” references: today’s “socialism” labels. Reframing the Du Bois and Washington debate.

The concept of exercising fugitive pedagogy — simultaneously infuriating that history has been erased from “mainstream” classrooms AND invigorating that there’s a strong, vibrant history of resistance and subversion.

Fugitive pedagogy and how it impacted Black teachers. I am amazed by Dr. Carter G. Woodson’s story and how he was a trailblazer. The history of Black educators and how they went through to ensure that they are educated are very important. Their history needs to be told, and the truth needs to be shared with people. I learned a new term: intellectual surveillance.

Private capital and intellectual surveillance being a part of the same struggle. As well as the beautiful historical lineage of Black teachers who engaged in a process of ‘imagining’ with their students (ours is not only a history of resistance or countering white supremacy).

I think that something that struck me and made me think about my teaching was when Dr. Givens talked about the narrative around desegregation of schools and centering the white schools, while not recognizing the amazing contributions of teachers at Black schools. I need to center my narrative around that idea and talk more about the success of Black schools in segregated times.

The limitations of the focus on antiracist pedagogy. And the fact that the previously enslaved wrote text books. I did not know. The concept itself of fugitively and as applied to the practices of Black educators.

Black literacy becoming criminalized. Hearing Dr. Givens speak the history and connect Dr. Woodson’s teachers to the project of teaching for liberation today, stemming from the rich history of Black teachers! So much fire this evening.

What will you do with what you learned?

I am going to be able to apply many of the concepts I learned today to my Ethnic Studies teaching, which is focused on histories of schooling. Also I teach History of the Americas and that brief bit on maroon societies across the Americas sparked a way for me to talk about resistance outside of Haiti and the U.S.

It will influence the framing of professional development sessions with my history team and lesson planning.

I will read Dr. Givens‘ book, and make sure to explore it with my students next semester. I needed to reframe my considerations of Woodson outside the BHM narrative. This was so helpful in giving me the inspiration to dig deeper — thank you!

Keep reading, keep learning more. I will also bring this knowledge back to my team tomorrow. I plan to propose “Fugitive Pedagogy” as our next team book study.

I am currently working on a model curriculum for 5th Grade the MA Dept of Education. Unit 5.5 of the Frameworks focuses on Black History from Reconstruction to the the Present. Dr. Jarvis’ work will be instrumental as I shape these lessons which will be open source for all educators in Massachusetts.

Teach about Freedom Schools and make comparisons to the banning of CRT today.

As a pre-service teacher, I am looking forward to challenging dominant narratives found in the state of Texas’ curriculum. I am still preparing ideas for how this can be done, but I really want to focus in on students identities in my classroom and have them work as co-creators of the classroom curriculum. I have faith that their minds and hearts will fuel the creativity needed to teach the truth, and challenge dominant biased narratives.

I plan to read the Carter G. Woodson picture book tomorrow, and then use that as a catalyst for moving forward with conversations about his work, the pushback that he received, why they think that was, and then move on to whatever our conversations make most logical. I work with first through fifth-grade students, so the conversations and next steps may vary by group. I am awaiting my copy of Fugitive Pedagogy & I know that this will continue to impact my practice. I’m looking forward to sharing about tonight with my T4BL study group members.

University teacher: I got so many resources from the chat and specific examples and framing from Dr. Givens. I already texted a few of my colleague co conspirators about ideas for refusing some of what we are asked to do in teacher education.

I hope to share this information formally and informally with younger teachers, especially Black teachers, to encourage them to remain in the profession.

Additional Comments

This is making me have hope about returning to teaching — about what I might still be able to do.

Thank you so much for these opportunities for on-going professional development.

Great hosts and knowledge as usual….#ScholarsOfThePractice

Presenters

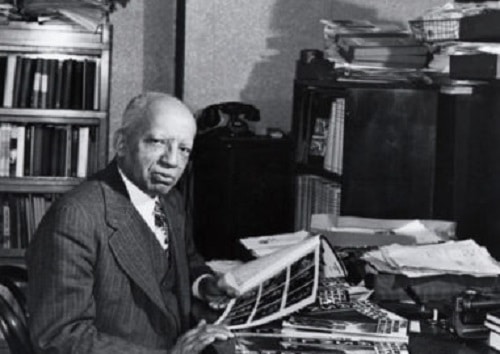

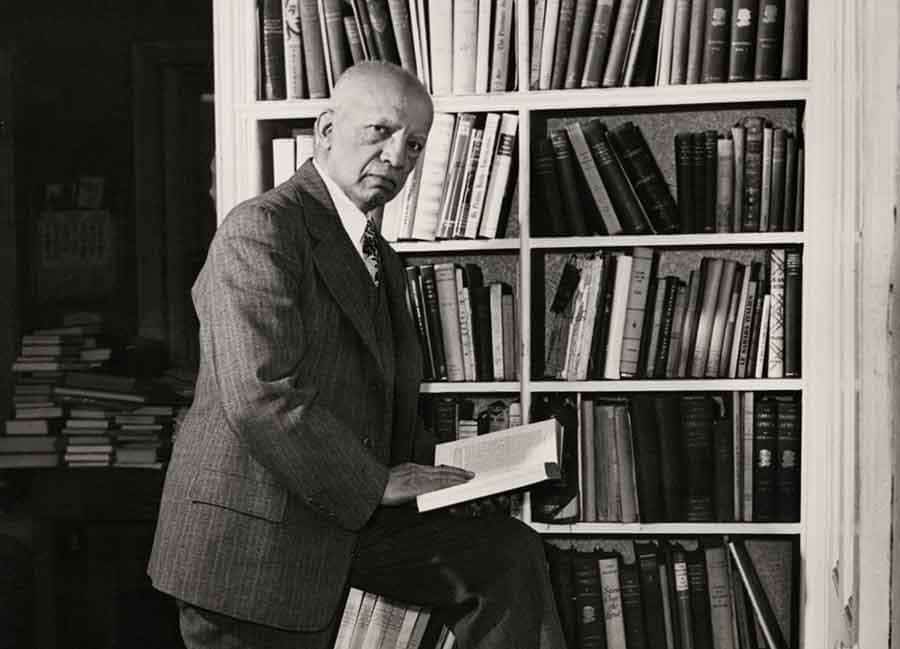

Jarvis Givens is an assistant professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and a faculty affiliate in the university’s department of African & African American Studies. He studies the history of American education, African American history, and the relationship between race and power in schools.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, and editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing.

Cierra Kaler-Jones is a social justice educator, writer, and researcher based in Washington, D.C. Her research explores how Black girls use arts-based practices as mechanisms for identity construction and resistance. She is the director of storytelling at the Communities for Just Schools Fund.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn