This article was written on the occasion of Staughton Lynd’s 80th birthday. He was born on November 22, 1929.

This article was written on the occasion of Staughton Lynd’s 80th birthday. He was born on November 22, 1929.

by Andy Piascik

Suddenly Staughton Lynd is all the rage. Again. In the last several years, Lynd has published two new books, a third that’s a reprint of an earlier work, plus a memoir co-authored with his wife Alice. In addition, a portrait of his life as an activist through 1970 by Carl Mirra of Adelphi University has been published, with another book about his work after 1970 by Mark Weber of Kent State University due soon.

In an epoch of imperial hubris and corporate class warfare on steroids, the release of these books could hardly have come at a better time. Soldier, coal miner, Sixties veteran, recent graduate — there’s much to be gained by one and all from a study of Lynd’s life and work. In so doing, it’s inspiring to discover how frequently he was in the right place at the right time and, more importantly, on the right side.

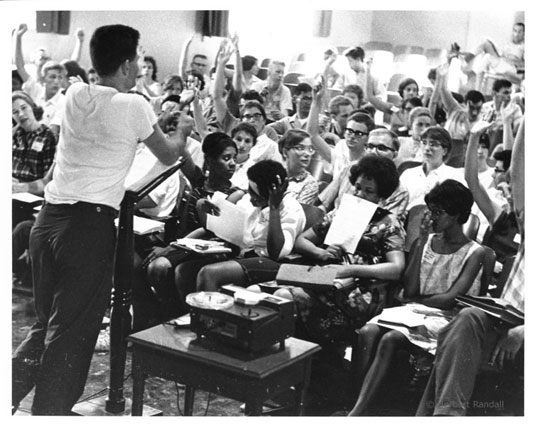

Forty-nine years ago, during the tumultuous summer of 1964, Lynd was invited to coordinate the Freedom Schools established in Mississippi by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The schools were an integral part of the Herculean effort to end apartheid in the United States and became models for alternative schools everywhere.

Staughton Lynd speaks with Freedom School teachers in Ohio. Photo: Herbert Randall

That August, Lynd stood with the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party at the Democratic Party (MFDP) convention. Led by Fannie Lou Hamer and Bob Moses, the MFDP had earned the right to represent their state with their blood and their extraordinary courage. Instead the party hierarchy supported the official, illegal delegation, a pathetic band of reactionaries who — the irony is too delicious — supported not Democrat Lyndon Johnson but his opponent, Republican Barry Goldwater, for president. This back-stabbing was carried out by liberal icons Hubert Humphrey, Walter Reuther, and Walter Mondale and endorsed, alas, by Martin Luther King.

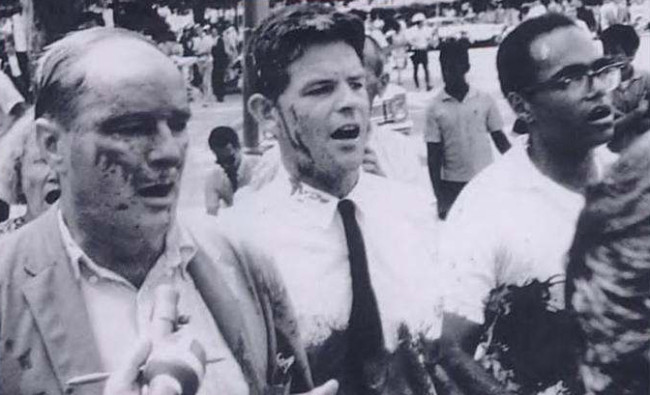

Dave Dellinger, Staughton Lynd, and Robert Moses at a protest against the Vietnam War in Washington, D.C. in August 1965. From the book Direct Action: Radical Pacifism from the Union Eight to the Chicago Seven.

In early 1965, Lynd spoke at Carnegie Hall in one of the first events organized in opposition to the U.S. invasion of Vietnam. A short time later, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) asked him to chair the first national demonstration against the war, where he was again a keynote speaker. That April 17, a crowd of 25,000 that was five times larger than even the most optimistic organizers had anticipated turned out in Washington, and what would become the largest anti-war movement in U.S. history was born.

That summer, Lynd helped organize the Assembly of Unrepresented People at which peace with the people of Vietnam was declared. It proved prophetic, for in a few shorts years, a majority of people in the U.S. had declared peace with Vietnam.

Lynd would continue as one of the seminal figures of the 1960s. He was both a tireless organizer and the author of numerous articles in important movement publications like Liberation, Radical America, and Studies on the Left. With co-author Michael Ferber, he documented the movement against the military draft in The Resistance, one of the best books about Sixties organizing. Lynd was an enthusiastic supporter of the New Left and embraced precepts like participatory democracy and decentralization.

Ex-radicals of his generation like Irving Howe, Bayard Rustin, and Michael Harrington, by contrast, spent much of the Sixties attacking SNCC and SDS. He spoke for many when he mocked their enthusiasm for Johnson and the Democrats as “coalition with the Marines.”

This, too, proved uncannily prophetic. Within a year of being elected in 1964, Johnson: 1) ordered a massive escalation in Vietnam; 2) sent an invasion force to the Dominican Republic to support military thugs who had overthrown a democratically elected government; and 3) armed and funded an incredibly violent coup in Indonesia in which over a million people were killed. The Peace Candidate indeed.

At the end of 1965, Lynd made a fateful trip to Hanoi where he witnessed the carnage inflicted by U.S. bombers. Up to that point, he was one of the most promising new scholars in the country.

Upon his return, however, his career in academia was essentially at an end. A tenure track position at Yale suddenly disappeared. Department heads at other universities enthusiastically offered teaching positions, only to be overruled by higher-ups.

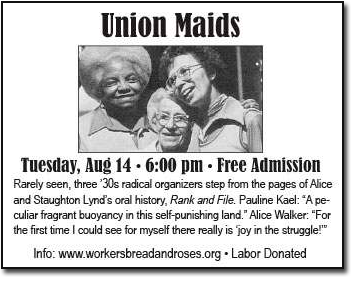

A 2012 flyer for event featuring women featured in the Lynds’ book “Rank and File” and in the film “Union Maids.” Source: International Workers of the World (IWW)

Lynd never looked back. He became an accomplished scholar outside the academy and one of the most perceptive and prolific chroniclers of “history from below,” with a special interest in working class organizing. From a series of interviews, he and Alice produced the award-winning book Rank and File, which begat the Academy Award-nominated documentary film Union Maids.

Lynd moved to Ohio in 1976, became an attorney and, when the mills in Youngstown began to close, assisted steelworkers in an unsuccessful attempt to take them over. In a book he wrote about the effort, Lynd explored the biggest little secret of all, one that people everywhere would do well to heed: We who do the work can build a better world, and we can best do it without the parasitic Super Rich who contribute nothing and weigh us down like a monstrous ball and chain.

Lynd is eighty-three now. The step is slower and his eyesight isn’t the best. Five years ago he had open heart surgery — “an affair of the heart,” he calls it. . . .

He talks of how deeply he misses dear friend Howard Zinn, who died several years ago. He talks of driving through Mississippi late at night, hopelessly lost, just days after civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Mickey Schwerner had been abducted and murdered. He talks of his remarkable life’s work with great humility and not at all wistfully, but in search of lessons it might hold, especially for the young. A teacher extraordinaire, he is guided by the principle that a teacher is also a student and all students teachers.

Lynd has seen more than his share of colleagues come and go. Some flamed out after a brief period of frantic busyness; others moved on to different lives and nice-paying gigs. Still going strong, Lynd offers long-term commitment (“long distance running,” as he calls it) and accompaniment — professionals living alongside workers and the unrepresented and contributing much-needed skills to the struggle for freedom — as alternatives. He also believes as passionately as ever that a better world is indeed possible.

—- by Andy Piascik. Piascik is a long-time activist and award-winning author who has written for Z Magazine, The Indypendent, Counterpunch and many other websites and publications. He can be reached at andypiascik@yahoo.com.

Read Staughton Lynd’s tribute to Howard Zinn presented at the Read-In held at Purdue University on Nov. 5. It is a condensed chapter from the forthcoming book Doing History from the Bottom Up: On E. P. Thompson, Howard Zinn, and Rebuilding the Labor Movement from Below.

Read the article, “Staughton Lynd: A Historian with a Place in History” by Carl Mirra discussing Lynd’s activism.

Books

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Videos

Staughton Lynd on Democracy Now!, January 4, 2011, discussing prisoner hunger strike at an Ohio supermax prison.

The film Union Maids, an oral history of three women labor activists who are featured in the book Rank and File.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn