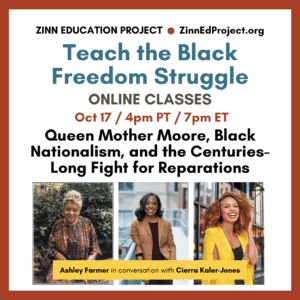

On October 17, the Zinn Education Project hosted author Ashley Farmer in conversation with Cierra Kaler-Jones about Queen Mother Audley Moore (1898–1997), one of the most influential activists and thinkers of the 20th century about Black Nationalism and reparations.

Farmer also shared stories from Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era, a comprehensive study of Black women’s intellectual production and activism in the Black Power era. Dr. Jeanne Theoharis briefly joined the conversation to discuss the decades-long relationship between Mrs. Rosa Parks and Queen Mother Moore.

Farmer also shared stories from Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era, a comprehensive study of Black women’s intellectual production and activism in the Black Power era. Dr. Jeanne Theoharis briefly joined the conversation to discuss the decades-long relationship between Mrs. Rosa Parks and Queen Mother Moore.

This class, part of our Teach the Black Freedom Struggle series, was an eye-opener for most participants. In a poll at the session opening, we found that 67% had never heard of Queen Mother Moore, while 15% had heard her name, but knew nothing about her. In another poll, we learned that only 6% of the participants had taught in-depth about reparations.

Here are a few reactions from participants who joined in from across the country:

I really loved learning about the history of Queen Mother Audley Moore and the way that she paved the way for the modern reparations movement.

I loved the stories (of course), but I also appreciated the peek into the professor’s classroom and the ways that students can change as they grow and the way they can practice new ideas of freedom.

In a breakout room, one teacher shared that at her school the teaching of Black history stops at slavery. Conversations about reparations are so important in these educational contexts. Cierra Kaler-Jones’ introduction of the power of narrative work furthered this conversation in the way that we must question “who is asking us to see history in this particular way?” I found the intersection of narrative work, critical history, and truth telling empowering.

Black women’s freedom dreams, like Queen Mother Moore’s, are often more expansive than their peers and can inspire us today. Each of us doing our part can lead to dramatic and needed changes.

The storytelling and anecdotes from Queen Mother Moore’s life were great — her childhood, the time she spent with Malcolm X, and her experiences with Marcus Garvey. The breakout room was great too — I love how the Zinn Education Project brings together educators from all over the country!

Event Recording

Check out the recording of the full session, except for the breakout rooms.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion. Some of you, many of you, I saw are joining us for the first time, and some have participated since we launched this series. It truly is a gift to be able to share this time together, and I thank you for being in virtual community with us. Today’s class is hosted by the Zinn Education Project, which is coordinated by Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change, and is hosting the session today as part of our Teaching for Black Lives Campaign. We offer free downloadable people’s history lessons that many of you have used. I’ve used many of them myself for middle and high school classrooms from the Zinn Education Project website. The ASL interpretation is provided by Krystal Butler and Shannon Morrison. I have the honor and privilege of being able to share a bit of a congratulatory note and some gratitude. So we’re going to share some slides, as I give you a little bit of a brief context. This series was launched in March of 2020, at the suggestion of people’s historian Jeanne Theoharis. She has helped us coordinate the series and has been a featured speaker [numerous times]. I can say personally that I’ve learned so much from Jeanne, not only with the content knowledge about history, but also with the way that she shows up, and the way that she shows up with so much love. Her book, The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks — I always have mine close by me — is being released as a film on Peacock on Wednesday, in just two days. So please, please join us in congratulating and thanking Jeanne for bringing this history to the people through not only a young people’s book, but now a film. We’re posting a collection of lessons developed by Jeanne and colleagues, along with other resources to bring the book and the film to the classroom. And again, thank you so much Jeanne for all that you do, and more importantly for the person that you are and all of the ways that you continue to show up and to challenge dominant narratives and really center people’s history. We’re grateful to you and for you. So before we begin the conversation, we want to find out who is in the room and go through our plans for our time together. We’re going to post a quick poll to find out how many teachers, librarians, teacher educators, historians, parents, students, and others are in the room with us. Many of you are in multiple roles, so we’ll just encourage you to pick your primary one. If for some reason you have any challenges with the poll, we’d still love for you to introduce yourself in the chat box — tell us who you are, where you’re coming from, so that we can continue the conversation. It’s looking like we have a lot of K through 12 teachers in the house — shout out to you all and solidarity for all that you are doing on a daily basis. And we also have members here from our Teaching for Black Lives study groups. If you are in one of those groups, please add T4BL after your name. And so as we continue to answer which role you most identify with throughout the session, we want you to use the chat box to post your questions, your comments, your resources, and ideas. We’ll also do a short evaluation at the end. And in about a week, we will share the full recording from the session and all of the resources shared in the chat box. We will make sure to get those resources to you. And also tweet what you are learning. So it looks like we are ready to share the results from the poll. We have 40% K through 12 teachers — yes, shouting you all out appreciating you and all that you do. We have to 2 % K through 12 students — so shout out to the students, thanks for being here. Four percent family members to students, 13% teacher educators, 9% historians, 5% librarians, and 27% others folks that are showing up and wanting to be in community and in conversation today. So tell us more about yourself, introduce yourself in the chat: we want to know where you’re coming from. Just so you know — because I know that there are many folks that are here for the first time — after about 25 minutes we’ll take a pause so that you can meet each other and talk in small groups to share your thoughts with one another, to share strategies, to share teaching ideas. So, without further ado, I’m so thrilled and so honored, please join me in welcoming Dr. Ashley Farmer, associate professor in the departments of history and African and African diaspora studies at the University of Texas at Austin. She is the author of Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era, and her upcoming book is “Queen Mother” Audley Moore: Mother of Black Nationalism. Dr. Farmer, I’m so grateful to you for being here, for being in conversation with us, and I can’t wait for all that we will learn together. So thank you, thank you, thank you. Ashley Farmer: Thank you. Thank you for having me. Kaler-Jones: Thank you. We’re going to jump right in with our first question. One thing that I love about your work — there are many things that I love about your work, but I’ll pinpoint my heart’s work — is really around storytelling for social justice, and you talk about the importance of narrative in your teaching. In your talk at the National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Institute last August, you said everything is a story, and asked students what narratives do you know? Why are textbooks this way? And, most importantly, who has invested in you learning history only this way? Who does that serve? And then also, what histories do you want to tell? I love those questions so much. So can you tell us more about what you mean? Why are narratives important, and what are narratives shaped by? Farmer: I’m going to be honest with you, I am a reality TV lover; unabashedly there is no brow too low for me. But I enter with that because I think it helps you understand that I like it because it crafts a good story — it’s riveting. I know that it’s not always true, it’s fictionalized, semi-reality, etc. But what it is is kind of a template for how we show up culturally, how we show up economically, how we show up politically, etc. And I’m fascinated by the narratives that we choose to tell culturally. And what’s really amazing about history in general is that that’s exactly what it is: a set of collective stories we tell each other about who we are, how much money we make, how we identify, who’s in power, who’s cool, who’s not cool, etc. And so I became a historian because I wanted to tell those stories. But also, I realized that just like with reality TV, a lot of those narratives are fake, or being spun in a way to make me believe a set of things — you know, when you see something on TV and then when you learn the true story. I mean, I think Jeanne [Theoharis]’s story of Rosa Parks is a really wonderful case in point of that — about the narratives that we have and why that works. So anyway, I think that it’s really valuable to think about what are we collectively invested in, who are we collectively invested in, and who benefits from that collective investment? And so if we think of history as just a set of collective investments, and stories we tell each other about the past, then we can start to think about whether or not those are the stories that really are true to what happened. And usually the truth is pretty juicy, so there’s no need to kind of paper over it. That’s what I always tell my students. But also, some narratives hurt people; and we see the real effects of that. I mean, to take my reality TV narrative or analogy a little bit further, once a certain set of people start to get stereotyped a certain way on TV, that really affects how people who look like them, act like them, live in that area, then live their lives. And history does the same thing. So I’m just really invested in thinking about how we collectively think about the past and how we can do that. I will also add that I think narratives are so ingrained — they’re such a key part of our cultural work — that we kind of start to blindly accept them. So one of the things that I think is really good about just naming them, and perhaps helping students deconstruct them, is that it also just develops their critical thinking skills. It starts to make you think everything around you isn’t a given, every story that you’re being told isn’t necessarily the truth because it’s been written in a textbook. And I feel like once they start to break those things down, you get different kind of race, class, and gender glasses, with which they see everything. And sometimes they even come back to me and tell me they see reality TV differently, so it comes full circle. Kaler-Jones: I love that so much, because one thing that you are pinpointing for us is examining power and how power shows up in the story, and who ultimately gets to share the story, who gets to distort [or] erase the stories, and really honing in on what that does to the narrative, and ultimately, how those narratives shape beliefs and values and actions, and whether or not we uphold or dismantle the status quo. So we’re going to be getting into a lot of storytelling today, because you have so many rich stories in your book, and just in your work overall. But before we get to the life of Queen Mother Audley Moore in particular, I would love to hear you tell us about your decision to focus on the lives of revolutionary Black women? Farmer: I think that one of the things that I love about the women that I study, or admire so much about the women that I study, is their political imagination. I think a lot of people look around and feel very frustrated with the way things are. But when we were talking about the narratives, sometimes you don’t know what new narrative to make, and what could be. And one of the things that I have found that the women that I studied do particularly well is offer really great ideas and understandings of freedom dreams. They have really expansive political imaginations. Why do they have them? Because they’re at the bottom of the totem pole. They’re the people that are most affected by race, class, gender, sexuality constraints, and so you have nothing to lose and everything to gain by imagining a totally kind of ending or reordering of the current systems that we live in. And so [do] some of their stories or ideas about how we should do things seem far fetched? Yes — otherwise, they wouldn’t be radical or revolutionary. But I think they offer us a compass, a way to point our intentionality, our way to move with purpose together. And while we may not always get there, when we have a compass towards where we want to go, we create a different set of choices, and we’ve created different sets of actions. So I found as a collective of historical actors, their work is just really inspirational in terms of thinking about expanding my political imagination. And so I think that’s why I’m drawn to them over and over again. Kaler-Jones: I appreciate that so much. And one of the things that I so appreciate about your work, too, is just the focusing on everyday, Black women, everyday revolutionary Black women. And as you were talking about imagination, I was thinking about some of the work of yours that I’ve read, and you’ve talked about the importance of using visual sources, like cartoons to teach some of these stories. I think that that could be really advantageous for our audience that is comprised of many educators. So can you talk about how Black women have expressed their politics through art? And how does that relate to how we can rethink what intellectual production is and looks like in the stories that we tell? Farmer: I’m certainly interested in the organizing that Black woman radicals and revolutionaries do. But I’m also really interested, like I said, in their thoughts: what they think their politics are, why their politics are this versus that, and how they tried to convince others to get on board with these kind of radical imaginings that we’re talking about. But one of the things that we have to keep in mind when talking about Black women in particular, is that the forms and formats of intellectual production — the things that we might go to most often when we think of political thought, like a speech, a treatise, a law — we weren’t able to do those things. We’re still often not able to do those things. Those are just not the forms and formats that are available to us. On the one hand, it can start to be a little bit difficult to find what we might think of as evidence of Black women’s political thought. But it also opens up our minds to different ideas of what political expression can look like. So, in the book I read about a woman named Alice Childress, who was a radical Black playwright. I read her satire about a maid who — it’s serialized, it goes in a Black newspaper — and she goes and works in a white woman’s home and goes home every day and tells her friend Marge about it. And even though it’s all fiction, through their interactions you get a sense of the politics and how Black women are moving in the world. Another example is the Black Panther Party newspaper. A lot of people don’t know that women drew a lot of those initial drawings in addition to Emory Douglas. And they often feature women more often expressing politics. If you think about what is more visually appealing, and what captures people’s imaginations really instantaneously, it is those beautiful mixed media drawings and figures that they made, that also express a form of politics by what the woman is wearing, or what the woman is doing. So, one of the things that I really tried to encourage myself to do, and others to do, is think about political expression and political imagination as being really, really expansive and found in a lot of different places. And I think that really opens up our minds to different understandings of historical sources. Kaler-Jones: Absolutely. And as you talk about being interested in thoughts and political expression, as we know, throughout history, these political expressions have been policed and surveilled. I think just recently, there was that piece that came out in the New York Times about how Aretha Franklin was surveilled by the FBI. And we have a lesson at the Zinn Education Project called Subversives: Stories from the Red Scare, written by my comrade, Ursula Wolfe-Rocca. We’ll place that in the chat box for you all. One of the figures that I had learned about as being surveilled by the FBI was Josephine Baker. We’re seeing how this political expression through art is being policed, is being surveilled, and just the resistance. So, how extensively were the women you studied tracked by the FBI, and what does that tell us about their role in history? Farmer: I love this question, because it’s kind of at the intersection of the work I’m doing, and where I’m going. I’m thinking about writing about Black women and COINTELPRO next. Through the counterintelligence program, or COINTELPRO, Black women were surveilled largely when it started in the 1950s all the way through, really, the late 70s. So under the Freedom of Information Act, I’m able to get some of the records released. They’re always heavily redacted; you never know if you got everything. But at least it offers us some record of how they were thinking about these Black women. It’s really actually an interesting subject, because I think a lot of people know about, say, the [Martin Luther] King letter, where [FBI director J. Edgar] Hoover and the agents tried to get King to kill himself. Or people are really clear about the way Malcolm X was surveilled. But we don’t talk a lot about the sustained psychological and economic and political terror that Black women endured for sometimes decades. Sometimes, like in the case of Queen Mother Moore, from like the 20s to the 80s — a long time of day-after-day surveillance. So, I think we have to ask ourselves a couple of things about that. From the activist side, women survived it, but at what cost? And how do we care for their stories and talk about their experiences with an ethic of care, but not let them get lost in the idea that state repression only happens to men? It just happens in different ways to women, and sometimes the same ways. And then also, what does it say that the government devoted so many resources to tracking these women for so long? How might that help us understand who they found to be political threats, even if they weren’t the same kind of major players and leaders in the movement that many of us know today? Kaler-Jones: Oh, this is such a critical history, and to think about the surveillance. I also appreciate the complexity and nuance that you’re bringing up of the ethic of care and being able to share these stories. So as we dive a little bit deeper into the storytelling, let’s take a deep dive into the life of Queen Mother Audley Moore. But before we do that, we’d actually like to take a quick poll [and] see how folks are thinking about this work. So the question reads: Before reading about this session, had you heard about Queen Mother Moore? And there is a second question: Have you taught about reparations? So the answers are: yes, her name sounded familiar but that’s about it; or no. And then have you taught about reparations? [The answers are] Yes, in depth; yes, but only briefly; not yet, but I have plans to; and no, but I’m curious to learn more. So once we finish up with this poll, we’ll post it. I’ll give some what’s coming up and then we’ll dive into a number of questions about Queen Mother Audley Moore. And I’ll say too, one of the things that I found interesting in reading your work, Dr. Farmer, you were talking about how she was surveilled in her 80s. So to think about this lifelong surveillance and what that means too when we think about the care and the wellness and the well being of a human who is doing this resistive work? What does that mean for history? I see people in the chat are excited for the deep dive. Farmer: Can I tell a little kind of tantalizing story about her and surveillance while we’re finishing up? Kaler-Jones: Absolutely, yes. Farmer: So, you know, none of these women are dumb. I want you to imagine a car creeping behind you every day, and you’re like, “Y’all aren’t slick.” Or, I want you to imagine somebody prank calling your house to see if you live there, right? They’re very clear about what the federal government is doing, and the FBI agents — they know all the tricks. So at some point, they say, she gets tired of them just calling up and acting a fool, so she says, “Fine, I’ll come down. And I’ll come to the FBI office for an interview.” So she’s just like, I’m not even going to hide what I’m doing, not going to try to pretend it’s not what I’m doing. And she goes in there, and then they put the transcript of her conversation in the FBI file. And she’s in there, she’s causing a ruckus, she’s asking them why they don’t have any Black agents. She’s asking them what they do around here. She’s asking them if they feel good about their lives, doing this to people. I also want to emphasize that even though this is very harmful to do to someone, there were these moments where they just kind of called it what it was and learned to coexist with it, and still didn’t back down from their politics while doing it. And people were very flustered by the fact of her coming in and just boldly proclaiming, she was like, “And what about it?” And I appreciate that about her. She’s like, “Stop calling me, stop following me. You know who I am, you know what I do.” They did not stop, but I appreciate her forthcomingness about that. Kaler-Jones: Yes, I love that so much. That is the energy we need, to just show up and be like, “What about it?” So I’m going to quickly read the poll results, and then we’ll do a deeper dive in. It says, “Before reading about this session, had you heard about Queen Mother Moore” and it looks like 67% of folks had not; 15% [said] her name sounded familiar but that’s about it; and then 18% said, yes, so very exciting to dig into this history. And then “Have you talked about reparations?” No, but I’m curious to learn more 45%. Not yet, but I have plans to 14%. Yes, but only briefly 35%. And yes, in depth 6%. So grateful for the folks that are here to do this learning, this collective learning, together. So, we just heard this incredible story. But could you please tell us about Queen Mother Audley Moore and early 20th century radical organizing? Let’s take it back a little bit and think about how she got started, and why does this matter? Farmer: What makes Queen Mother Moore’s story so great is that she lived from 1898 to 1997, so basically the entirety of the 20th century. And her last public appearance was in 1995, to give you a scope of the breadth. So, you should think of her as kind of a traveler through every major moment in Black radical or revolutionary politics. She was born in 1898 in New Iberia, Louisiana, which is a small town outside of New Orleans, about two hours away. And she was actually born to this really elite adult life; in her words that her whole family was planning on her being “a bourgeois little stinker.” She was primed to be among the Black elite. But it just so happened that both of her parents died when she was relatively young, and all of a sudden she kind of slid down the class ladder very quickly, and had to take up work to take care of her siblings. So it’s during this point — we’re talking like 1918, 1919, the early 20th century — that she meets a Jamaican sailor and he introduces her to Garveyism, to Marcus Garvey’s UNIA [the Universal Negro Improvement Association]. Then, New Orleans [was] a Garvey stronghold. And the story she tells, that kind of radicalized her on the spot, is that Garvey was coming to New Orleans, which is true, and he wanted to speak and the white police officers were like, “We’re not having it,” because having a Black Nationalist come and rouse people is never a good idea for them. So she says that Marcus Garvey comes back and the police are ready to arrest him. Everybody comes back and she’s got a gun in her boot, one in her pocketbook, and they all jump up on the benches, and they pull out their guns like this and they say “Speak Garvey, speak” in unison. And she says that the white police officers go out with their tails between their legs. Now, is this true? Possibly somewhat. But more importantly what it is is a story of her seeing Black self-defense and Black self-determination and action in relationship to Garvey. And she says she signs up for the UNIA then and there, and she really is a lifelong Garveyite after that. But she’s also emblematic of somebody that travels through the different spaces of Black radical politics in the early 20th century. So she works and organizes with the UNIA, but as you may know, Garvey’s movement dissipates when he gets deported for mail fraud. And what’s there to take its place? The Communist Party. Why is the Communist Party the go-to-place for people like Audley Moore who are dyed in the wool Black Nationalists? Well, in the late 1920s, they declared Black people are a nation in the Black Belt and have the right to self-determination. They say we share an economic condition, a cultural plight, a political condition, a shared culture, the kind of makeshift, or the definitions, of a nation. And they also defend the working class every day. When people are getting thrown out because they can’t pay, the rent the Communist Party [were] the people that put them back in. When people are being lynched, the Communist Party is out protesting against them. So she literally says, I went to this movement and they were cognizant of what Garvey was speaking of, so I thought it’d be a good vehicle to help my people. And so really, if you think about the two major movements of Black radicals from say 1920 to 1950, or even 1910, it really was the UNIA and the Communist Party. And she is somebody who found spaces in both of those movements to adhere to ideas of Black nationalism, to adhere to ideas of Black self-determination, and to just organize on a daily basis to help Black working class people. And coincidentally, when she starts to become a working member of the Communist Party she rises up in the ranks in Harlem, [and] that’s when her FBI file starts. Kaler-Jones: Yes, absolutely. And so you talked a little bit about early 20th century radical organizing. As we move forward in history just a bit, how did she keep radical politics alive when the nation really was turning towards integration in the mid 20th century? Farmer: As many of you know, by the time we get to World War II, it is not popular to critique the nation state. You kind of have to back away from some of the critiques of capitalism and move towards what we would call a popular front, or kind of a liberal/progressive organizing. She’s a big time organizer there, but still keeps focusing on two things even as she’s organizing for the war, which was self-determination and self-defense for Black people. She continually defends those who have been charged with self-defense, including Black men and women. And she tries to always move war resources, war conversations into control of communities by Black people. Eventually then we get to the 1950s, where it is obviously immensely unpopular to be a communist, because we get the start of the Red Scare. And I think she sees the writing on the wall. She was in New York when she was organizing with the Communist Party. And she goes back home to Louisiana. I think this was an effort to lay low, kind of get off the radar. But it’s also a moment where she’s working with what we would call the grassroots level, or the lower frequencies, to keep Garveyism and Black Nationalism alive. So she starts a group called the Universal Association of Ethiopian Women. And you can see the Universal Association of Ethiopian Women, the Universal Negro Improvement Association, you can see what she’s doing there. And it’s in this particular group that she argues she brings back the idea of a separate nation for Black people. And she also organizes on behalf of everyday people. And she starts the reparations movement. So I want you to think about this as being juxtaposed to the same moment that, say, the [Montgomery] bus boycott is happening, or desegregation struggles are starting. And so in a moment when probably more and more Black people are thinking integration is viable — and that’s a reasonable thing to think — and becoming more mainstream, Moore is avidly against it. She’s absolutely against the March on Washington, and she’s really still promoting not integration or entry into the American nation state, but separation and Black led and defended communities. Kaler-Jones: Wow. She is just this hardcore organizer in so many ways, shapes, and forms. And to think about her in this time period of history and the work that she’s doing. Can you tell us about what her relationship was like with some of the Black Power luminaries such as Malcolm X or Robert F. Williams, and even tell us a little bit more about some of those luminaries? Farmer: She’s organizing in the 20s, 30s, and in the 40s, 50s, early 60s, when maybe this nationalist moment goes out of style, she’s still keeping the flame alive. And then as many of us know, by the mid 60s to early 70s, Black Nationalism and Black Power are making a resurgence — in some part because of the limited gains of integration, but also because people like Moore have been advocating for it all the time. They never stopped; it wasn’t this either/or. So a lot of the folks that have been considered the leaders of this period of what we would call the Black Power movement, or the Black Power era. One is Malcolm X, who we all know. I’ve talked to many people who say that Malcolm would come and learn at her [Moore’s] feet. For a time she lived in Philadelphia, and he was organizing in Philadelphia and New York. I’ve talked to many people who say he would come by her house and learn about the organizing of the early 20th century. And she personally credits herself with helping him expand his views. She was always very critical of Elijah Muhammad, she was very critical of the Nation of Islam. And she always — with her Garvey-leanings — wanted him to think about a diaspora of Black people, not just Black people in the United States. So she would say that she in those conversations kind of pushed him along that way. I’ll say that we can kind of go back and forth, we may never know the extent of it. But I was looking at Malcolm X’s papers in the Schomburg recently, and her address in Philadelphia and her address in New Orleans are both listed in his address book. So I think that there is reason to believe that she was in communication and in conversation with him. Another great figure from this period is Robert F. Williams, who organized with the NAACP in North Carolina, and was actually kicked out for his support of self-defense. He eventually becomes as he moves into exile — he was fleeing charges of kidnapping that were not true — becomes kind of a Black Power icon. Somebody that is friendly with Fidel Castro, somebody that goes to China, and really advocates for a full-on revolution for Black people in America. We have lots of evidence of correspondence between him and Queen Mother Moore — particularly when he was in exile — talking about which way the movement should go, what people should be studying, what kind of plans they should be making for advocating for reparations, for Black separation, etc. So I bring this all up to say, at this point, if we’re talking about the 60s or 70s — remember I told you Moore was born at the end of the 19th century — she’s actually in her 60s or 70s. And this is where she gets this name of being the “Queen Mother” of the movement. She’s now an elder by the later 20th century, and younger revolutionaries and radicals are talking to her because she knows how to sustain a movement, and because she’s well-read and literate in political organizing. Kaler-Jones: This is such fascinating history. You said something at the end that I would love for you to quickly expand upon before we go into breakout rooms. Can you tell us even more about why Moore is considered the mother of the modern reparations movement? Farmer: The reparations movement as we know it — or how we think about Black people and reparations — is really a movement driven by Black working class women. Its first iteration was right after the Civil War, when a woman named Callie House from Rutherford County, Tennessee — not too far, actually, from where I grew up — started a movement to get pensions for ex-slaves. So, payment from the government for the work that they did in the past. She was caught up on mail fraud charges as the government is want to do — are you noticing a theme here? And the movement kind of died out for a while. But it was Moore in the late 50s and early 1960s who resurrected this kind of organizing, this grassroots organizing, to file a claim with the American government for reparations. So certainly there were people that were still doing it, but she was the one that kind of started a grassroots movement that took hold in sectors across the country. She says that she did not know of House, that she found a kind of religious saying that people needed to appeal to their captors within 100 years. So if you think about 1865 being the end of the Civil War, she was saying by 1965 Black people needed to make this appeal to the captors. But In reality, what really is happening here is she’s using that as the basis to get people onboard with a sense of urgency about filing a claim for such a thing. And I want to reiterate that at the time this seemed incredibly fringe. But she got people onboard with filing claims all across the country, and organizations and lawyers incorporating across the country. She would go on a tour talking about this in order to get people to think about reparations. And one of the things that I think is really great about her approach is 1) she was willing to appeal to the U.S. government — she thought money was owed. But it was not just for Black people to continue on with their lives as usual — she wanted to use that money as the basis of a separate claim for a separate community or a separate nation state. So, you see this kind of interesting strategy of simultaneously critiquing the American government, but also appealing to them for that. And most people that you talk to in the 60s, 70s, 80s — including some of these Black Power luminaries that I’m talking about — really credit Audley Moore with being the person that first kept pushing this idea before it was popular, and part of popular parlance. Kaler-Jones: Now I’d like to welcome back Dr. Farmer as well as Dr. Jeanne Theoharis, so we can collectively celebrate the documentary that’s coming out in just two days on Peacock. Jeanne is actually going to talk to Ashley about the intersections of Queen Mother Moore and Mrs. Rosa Parks. I just want to mention a couple of things — that the documentary has already been nominated for Best Biographical Documentary for the 2022 Critics Choice Documentary Awards, and today Jeanne was on Democracy Now! to talk more about the film. So excited about not only the film, but the lessons that will accompany it, and all of the ways that we can bring this learning and your work, Jeanne, to the classroom. So I’ll pass it over to you to continue the conversation. Jeanne Theoharis: Okay, now I can unmute. So first, thank you so much, Cierra. It is so nice to be together tonight, in this week that the film is coming out, because in many ways I think many of you have been with us on this journey, and with me on this journey, about Rosa Parks. Probably the thing I am most excited about is we have developed this whole curriculum suite around the film too — as Cierra and Jessie and I like to call Rosa Parks, she’s sort of a Trojan horse for teaching a lot of different things. The lessons really allow people to go in a lot of different directions. So Cierra Kaler Jones, Jesse Hagopian, Tiffany Patterson, Jessica Rucker, Ursula Wolfe-Rocca, and Say Bergen all helped with the lessons and then Deborah and Bill and [the Zinn Education Project] are really putting it out into the world. So it’s just so exciting and so beautiful. As all of you know, I can relate everything to Rosa Parks. But in fact, there is an incredible relationship, a decade’s long relationship, between Rosa Parks and Queen Mother Moore, and so we thought it would be a nice segue back to Queen Mother Moore, because it’s super interesting. When I was first researching, really unexpected for me, [was] when Queen Mother Moore starts to pop up in places in Rosa Parks’ life, and then I realized that they are friends. And people would say, “Oh, yeah, they used to sit in the front row together. They were here sitting in the front row together. They were there sitting in the front row together.” I was like, wow. And then I think Ashley knows a lot more even than I was able to figure out. So, back to you, Ashley. Farmer: There we go. I think I’ll highlight two moments that I think really encapsulate the longevity of Parks’ and Moore’s relationship. One is if you look on the Library of Congress website, and you put in Rosa Parks papers, you will find a letter from Queen Mother Moore to Rosa Parks about that organization I was telling you about, the Universal Association of Ethiopian Women. The group that was started in the late 50s, early 60s, that was advocating for reparations and separation. And she’s really interested in getting Parks onboard with supporting the organization, and in particular reparations. Which I think is really interesting because everything I have told you kind of suggests, if you believe the narratives that we talked about at the beginning of our session, is that Parks is on the integrationist path, and Queen Mother Moore is on this Black Nationalist path, and none between will meet. But as Jeanne has taught us, Parks was a far more dynamic and politically interesting and expansive figure than we’ve ever really been told. And her and Moore found lots of points of congruence. One was when they would go to the Black Power conferences together. Queen Mother Moore, again, was an elder by the 1960s. It’s a series of conferences that took place between about ‘66 and ‘68, where people were trying to think about forming separate Black political parties, separate Black nations perhaps. The stories go that if you were there, if you were in the hallway, you saw Queen Mother Moore in her regalia telling you reparations, reparations, reparations, and you would often see Parks beside her, or sitting beside her, at these events. I mentioned to you that Moore was active until the late 1990s. Her last public appearance was at the Million Man March in 1995. And Parks was there as well. There was actually this section of the program, the Mothers of the Movement, and there they had Dorothy Height, Maya Angelou, Betty Shabazz (Malcolm X’s widow), and they’ve got Parks and Queen Mother Moore. So that should tell you about how their lives are kind of intertwining, but also the ways in which they are respected figures in the movement. I often say if we want to talk and traffic in those narratives, we would think of Rosa Parks as birthing a modern Civil Rights Movement, you should think of Queen Mother Moore as kind of midwifing a modern Black Nationalist movement, in that way. Kaler-Jones: Wow, that’s so fascinating to hear the intersections. And I see Jeanne’s comment in the chat that they literally sat next to each other in so many spaces, and to see how they converge in that way, with their ideas and their orientation to the work. So you mentioned Black Nationalism. How does Moore challenge our traditional understandings of Black Nationalism? Farmer: Black Nationalism as a political philosophy, we’re talking about the idea of Black people being able to exercise community control, self determination, and self-defense. And to what end? Some of that is for an actual physical place that would constitute a nation. But more often than not, it’s kind of a metaphysical or figurative nation — this idea that Black people are bound together, even if we’re not technically making claim to some land and within a geographical boundary. But if you have heard these things being advocated for, you’ve probably heard them being advocated for by Black men, right? Whether that be Marcus Garvey, whether that be Malcolm X, whether that be Robert Williams, like I told you about. And so I think Moore really was a central architect of what we would think of as 20th century Black Nationalism, even though we only give that credit to the Garvey’s and the Malcolm’s, as I’ve explained to you. But also, she really — by taking on this persona of Queen Mother — was really able to be in a lot of the central places where Black Nationalism was being practiced and theorized. So what do I mean by that? Black Nationalism, in some ways, recapitulates very standard gender norms: Men are the heads of the nation, women are the mothers and the molders of the nation. And so that would leave Moore out of a lot of the central kind of decision making circles to which modern Black Nationalism owes its stuff to. And she’s a lot older than a lot of these folks as well, being born in the late 19th century. So by becoming a Queen Mother, all the sudden she’s an elder to be respected, and her advice is to be sought, and that makes it okay for her to be in these spaces with all-male groups all the time, when normally that would not be seen as something that was okay for a woman. And it also, I think, helps her stay relevant far past what people would be considering her organizing prime. When we think about organizing, we think of it wrongfully, but nonetheless we think of it as a young person’s game, right? And so by continuing to take on this elder position, she enables herself to stay present. So if you talk to organizers in the grassroots and especially in places like Mississippi, they’ll say Black Nationalism is the child of Malcolm X and Queen Mother Moore, the political child of Malcolm X and Queen Mother Moore, and I think that is in fact the case. Kaler-Jones: Wow. We’ve talked a little bit about Queen Mother Moore and the relationship to Malcolm X and some of the men of the movement. And I see a couple of questions in the chat box that I’ll pull together. I think that in talking about Mrs. Rosa Parks, many people were sparked about other folks, too. And so folks in the chat are wondering about Queen Mother Moore’s relationship with organizers like Angela Davis and Ella Baker and Septima Clark. Farmer: Great questions. Now, Ella Baker and her were well-known to each other and moved in and out of circles together, particularly in Harlem with political organizing. But I don’t have as much evidence about Septima Clark or Angela Davis. One of the things that is complicated about Moore is her gender politics. She was also human, and so I think that she did not — she was certainly in support of somebody like Angela Davis, and organized for her release as a political prisoner, as she did with many other political prisoners — but as I mentioned before, part of her ability to stay relevant was dependent on her being sought after by Black male leaders. And so I don’t think she forged as good of relationships with younger Black radicals, because I think she felt a little bit of a scarcity model in that sense. That also said, the young Black women did not love her because Queen Mother Moore had, like I said, some problematic gender politics, by every stretch of the matter. But she was who she was, and that included promoting polygamy as a way to counteract disparate rates between Black men and Black women, and the mass incarceration of Black men. And she bought in a lot of times to this very masculinist Black Nationalist ideal, even as she herself was flouting all of that. Like, it didn’t apply to her, but it applied to all the other women, particularly the young woman. So if you talk to younger activists, particularly those that were organizing, say in the 60s or 70s, like [Angela] Davis, they are appreciative of her struggle, think that she was had a shrewd and political acumen and organizing strategy, but found it difficult to meet with her because they felt she kind of talked down to them and tried to impose her gender politics on them. So you know, folks are human. And that was that. Kaler-Jones: That’s so fascinating, and I appreciate you just naming that, that they’re human, every day. Farmer: I mean, people can be very radical in some respects, and conservative in others. And that’s a perfect example of where she’s literally the first person to sign a declaration for a Black nation when tons of men sitting in the audience would not do it. But by that same token, she thinks that men should run that Black nation and women should fall in line. She is not part of it. But everybody else has to follow gender roles. Kaler-Jones: Wow, oh my gosh, wow. And one connection I’m making in my mind about something that I read of yours — so you talk about Moore’s reparation activism, in particular. And these are your words, “as revealing her commitment to a diverse concept of a reparations movement that offered multiple entry points for activists across the political spectrum.” So even with these problematic gender politics, can you talk more about how she did this? Farmer: We might think of reparations as symbolic in the sense that maybe it’s an apology, or maybe it’s a monument or a testament to something. We might think of reparations as a payout of either money owed from labor that was performed without funding, or as retribution for a long period of sustained racial and psychological terror. Or you might think about reparations as programs put in place — like job programs or housing programs — to redistribute or help reinforce or level the playing field between Black people and white people after years of injustice. And then you might think of reparations as just an actual paycheck that people are able to do whatever they want with. I would say that over the course of her reparations activism — which we’re talking, if she’s starting to think about this in the late 50s, and I’m telling you she’s passing away in the 90s, she’s thinking about this for almost half a century — her thinking about reparations and what it could look like evolves over time. And so if you drop down in different moments of her life you will see her advocating for different ways of reparations. Some of that, like I said, is appealing for a payout. Sometimes in pamphlets she’s talking about government programs to level the playing field. In other moments she is talking about acknowledgement from the American nation state of the wrongs done. But what that kind of diverse understanding of repayment and repair does is allow different people different entry points into advocating for this cause. I think that’s one of the things in which she was incredibly expansive and imaginative in that way. And so some folks maybe couldn’t get onboard with like, “We’re gonna take the money and form a separate nation,” but they could get onboard with government programs that leverage the playing field for jobs, or schools, or employment. Or maybe they can get onboard with saying, “If you can trace your lineage, you should get a paycheck for that unpaid labor of your ancestors.” I like to think of her as kind of a watering can sprinkling water and letting the flowers of reparations bloom in all kinds of places. So the folks in Philadelphia wanted a separate nation, the folks in LA were a bunch of lawyers that wanted the government to give a paycheck, and she was supportive, and kind of the patron saint of all of those different ways of thinking about this. Kaler-Jones: It’s interesting because it feels like she’s going about a narrative strategy where she is knowing who her audiences are, and then ultimately tailoring the message, but still staying strong to longer-term, seeing the larger picture, which I think is a really powerful blueprint for how we might think about that kind of organizing today. So, I’m going to shift my questions a little bit, because there’s a question in the chat. And I also have a couple of questions related specifically to teaching. Sydney Stewart in the chat asks, “What recommendations do you have for educators in lifting up Queen Mother Moore’s contributions, but also, as we’ve talked about the complexity and learning spaces?” Farmer: That’s a great point. I think that there’s a couple of different ways that you could approach it. One would be, as we’ve talked before, offering a couple of pages from the FBI file. It offers an opportunity for students just to see that dynamic in play, but also think about what it must be like to do this kind of work under the heavy weight of surveillance, which we don’t talk about enough. And separate from that, I think she has a wonderful pamphlet that you can get a scan from, from most libraries, that is called Why Reparations, and it details her intellectual rationale for it, and some of these programs that I’m talking about, or I’ve referenced before. So a great lesson plan would be for students to read through that and think through the reasoning of what she offers. The thing that’s really interesting about that particular pamphlet is that she references both American payouts to say those who were in Japanese internment camps, for example, but also other forms of reparations that have been paid globally. So it’s clear she has a globally conscious mindset about it. So thinking through that with students would be helpful in what reparations might look like in their communities as well. Or if these programs seem feasible, why or why not? And then, I think that there are several oral histories that have been published of hers. And the oral histories are where you really get a sense of these gender politics. They’ll ask her things like what is the role of women, and you will cringe at the responses that she gets. One of them is published in a journal called The Black Scholar, for example. In one part of the interview, she’ll be offering this wonderful assessment of reparations, or of racial terror and the American nation state, the next thing she’ll be like, husbands for five women. And so you might just ask students to read through that and say how do we understand this person. If we had to make a graph or a plot of politics at this particular moment, what things will we consider kind of reformist, radical/revolutionary, conservative? And what does that tell me, tell us, about the complexities of people as human beings? Kaler-Jones: I love that so much — the complexity of who we are as human beings. One thing that you lift up in a lot of your work is how people evolve over time, and how organizers and activists have changed their politics. And one thing that you wrote that I read, you had said we don’t wake up woke, right, we develop those politics over time. And so I just appreciate you lifting that up as a teaching strategy, to explore what that might look like in the classroom. Farmer: I think this is something that in particular, Jeanne, does very well. We kind of strip away these narratives of heroism and talk about people that we know in history as just people that looked around them and made a set of choices. And those choices had big reverberations, but nonetheless they were regular people presented with a set of choices, and they made the choice that they thought was the best at that moment. It helps us see ourselves less a little bit as people that have to be these martyrs for a movement, and just say, “Everybody has a set of choices, and we can try to just move the way that we want to see the world go.” And sometimes people have missed steps. Everybody evolves, right? I always tell my students, “I don’t know what the opposite of canceled is; I call it being rescheduled.” I know that’s not right, but I don’t have a better word. But I bet Moore would be canceled for those kinds of politics now. So, everything is also really historically specific. We need to make sure that we understand people as evolving in their politics, but also understanding that they may be reacting to different things in their different times. And instead of condemning somebody, think about what in their life should be espoused. Queen Mother Moore, when I’m talking about the gender politics and how she didn’t gel with younger activists, I mean, she’s almost 80 years older than them. It was a whole different world in which she came of age. And so that doesn’t mean that she doesn’t have to adapt, or that she should not be critiqued. But it helps us provide insight as to why maybe comparing her with somebody that is coming of age in a feminist movement might look a little bit different. Kaler-Jones: Speaking of evolving, as we’re also talking about teaching strategies, one thing that I read about your teaching is that you do a freedom reflection exercise in your class. And I found the questions that you used to be really thought provoking, and might be really helpful for so many of the educators on this call. So, could you talk to us a little bit more about the freedom exercise? Farmer: So I teach here in Texas, which, as many of you can probably attest to, is a wild time to teach Black history in Texas. But I teach a big intro to African American history class, we’re talking 100 plus students. A lot of them, because of the standards of Texas history, have never had a whole kind of understanding of Black history, and they’re mostly in my class because the school requires them to take two semesters of U.S. history [and] two semesters of Texas history. So this is their U.S. History requirement. So I set that as the basis to say that many of them come with very little knowledge of African American history from the start. There’s nothing that I am teaching them that they really can’t learn in other books and online. The value of the classroom is that we come together to discuss it and we hear each other’s perspectives and points of view. Also, to think about, once we assimilate knowledge, how we might behave differently because of it, right? So at the very beginning of the class, I have them write a reflection and ask them three things. One, to rate their knowledge of African American history on a scale of one to ten. Two, think about what they think is the biggest problem facing Black people today, and what that stems from historically. And then three, what do they think would solve that? Then we go from we’re talking like the 1400s all the way to Trayvon Martin in one semester. It’s quite the Odyssey, right? And then at the end, I ask them to reassess their knowledge of African American history — because we all know they need to be told that they learned things. Because they’ll swear they didn’t, otherwise. I asked them, do they still believe that the thing that they thought was historically the problem, the root of racial oppression, is the same. But then the third thing that I always ask them to do is say, now that you know, now that you’ve had the privilege to sit and examine this for a whole semester, how will you behave differently? One on the individual level, two on a communal level, and kind of a family communal level, and then three, on our campus level. And I’m not asking for huge acts; I’m not asking you to always stage a protest. But what I’m emphasizing is that it is okay that you did not know. That is why we’re here. There is no better place to not know something than to come into a classroom. That’s exactly my job, to teach you this. People always say it’s not my job, [but] it actually is my job. But once you know, you have a responsibility to those around you to use that knowledge to move differently through the world. And so I’m less concerned with whether they know every little amendment and every little year, but I am interested in them walking away with an ability to see and empathize with the Black experience differently, and try to make adjustments in their lives, that makes us move towards a community that is more caring and empathetic. So that’s the goal. And usually, their historical thing that they think was the root of oppression is quite different, which is a testament to them rethinking in that way. But sometimes they’re just simple things. They’ll say things like, “When I hear everybody’s sitting around in the dorm room, and they start talking about Black people in this way, I’ll intervene and just say, ‘Actually, it’s really harmful. And that perpetuates the stereotype.’” Or some of them say, “I’m going to share some of the sources and read them with my parents who I know have no idea what’s going on.” Some of them make bolder proclamations, but I find the ones where they just are willing to say they’re going to make a slight adjustment and think about their awareness of the world around them differently to be incredibly rewarding. Kaler-Jones: That’s so moving. Just a reminder of how the classroom is this site of possibility, but a site of action, a site of evolution, and experimentation and exploration of this history and also of ourselves and what our role ultimately is in the history that we make every day. So, I have one final question that will bring us to the current moment, and hopefully we’ll tie all of the pieces together. But right now, of course, we’re seeing 42 states and counting where there’s legislation banning critical conversations about racism and oppression in schools. And so with the history of Queen Mother Moore, thinking about conversations about reparations, thinking about conversations around Black Nationalism, all of that, in many places, cannot be taught. So what are your thoughts on the attacks on teaching the truth about United States history? And how do they relate to many of the stories that we talked about tonight? Farmer: I mean, I’m right there with you. I think there’s a bill to come in, I think, audit every class that takes CRT [Critical Race Theory] and tenure anybody that teaches it at UT [University of Texas] that is going to be voted on in the next week. So, it is an interesting time to be sure. I would say a couple of things. I think one of the things that Queen Mother teaches me is that this isn’t new. And I take comfort in that. Because when you realize that it’s not new, that people have been through it before and endured it before, you kind of know that we’ll still be here in the end doing what it is that we do. She was certainly under attack for her beliefs, and her teachings, and she kept on keeping on. And she endured it and is now being heralded and getting biographies written about her. So, that’s fine. Two, I think that these folks that have traditionally had to address these subjects outside of formal institutions have offered us a little bit of a roadmap. And to me, that is Freedom Schools, not unlike what we’re doing now. And what we may have to do for our students — I’m not suggesting that we don’t continue to fight these bills as they come down the line — but that does not mean that we have to wholesale stop talking about it. We may just have to shift the venues with which we talk about it. But one thing that teaching students in a state where they’re actively trying to do this has taught me is that the students really do have a real appetite for it. And if you build it, I do think that they will come. So I think we have to all rely on our networks to continue to try to do that as much as possible. We also have to keep having community. Part of what this is about, I mean, they don’t really even know what they’re saying, and nor do I think they really actually care. It’s just they want somebody to glom on to, to be the target of this. And so we need to make sure that we stay in community with one another, that we understand that that’s what it is and not to get distracted from that. And if we see folks that we care about in our community becoming the target of that, be ready to support and stand up for them as much as possible in that case. But, we will get through this, is what I would say. And, as people have done it before, we know that it’s so scary for exactly the same reason that we talked about what we got on today — it’s because what happens when our students know the truth. They’re afraid of how they might behave differently, they’re afraid that they won’t be able to have the same level of power and keep people in trance by these kinds of Disney-like narratives of what the history is versus what actually is. So as much as we can continue to push that and empower our students to say that the truth really is a path to a different world, then I think that we’re on the right path, and we’ll be okay. But in the meantime, I want to emphasize that it also sucks. I mean, I don’t want to downplay people’s real experience with this. Like, people will be okay. I may or may not be targeted, but I will be okay. But there is real trauma involved sometimes in becoming the target of these things, in the process. And so I want to reassure people that there is community and that they are on the right side and doing the right thing, without also saying that when you become the target of some of these things, it can be scary for a time. I don’t want to minimize people’s experiences, even while saying that I don’t think in the end it will be alright. Kaler-Jones: Yes, yes, yes, yes. And solidarity to all of the educators, all the librarians, the organizers, the activists, the family members, the students, everyone who is on this call that continues to teach truth and to seek truth and continues to promote the truth because we know that this is our path to freedom. It’s our path to liberation. And so I want to end with a quote from your writing, and I think that it will hopefully tie together this conversation and bring together Queen Mother Moore, but also thinking about learning this history so that we can dream new futures. And so in your words, Dr. Farmer, you said, “Queen Mother Moore certainly meant that African Americans deserved and should demand repayment. But her larger message and her contribution to the Black Freedom Movement was to show that through a reparations movement, organizers could reckon with each other and their troubled past, as well as chart a course toward a collective self-determining and self-governing future.” And so with that, I want to say thank you, thank you, thank you. While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Transcript

Cierra Kaler-Jones: Welcome, everyone. I am so excited for this conversation. So very excited that I wore my Cite Black Women shirt today specifically for this conversation. I’m really looking forward to diving in, and on behalf of the Zinn Education Project, we would like to welcome everyone to our class with Dr. Ashley Farmer on Queen Mother Moore, Black nationalism, and the centuries-long fight for reparations. I’m Cierra Kaler-Jones, a member of the Zinn Education Project leadership team.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Audiogram

This three-minute audio excerpt describes the role of Queen Mother Moore in popularizing the demand for reparations.

Resources

Here are many of the lessons, books, articles, and more recommended by the presenters and also by participants.

Lessons and Curricula

|

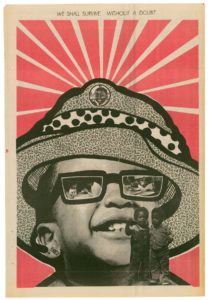

How to Make Amends: A Lesson on Reparations by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca, Alex Stegner, Chris Buehler, Angela DiPasquale, and Tom McKenna (lesson) Repair: Students Design a Reparations Bill by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (lesson) Subversives: Stories from the Red Scare by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (lesson) Teaching With Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (lesson) |

Related Books

|

Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era by Ashley D. Farmer (University of North Carolina Press) New Perspectives on the Black Intellectual Tradition edited by Keisha N. Blain, Christopher Cameron, & Ashley D. Farmer (Northwestern University Press) A Black Women’s History of the United States by Daina Ramey Berry and Kali Nicole Gross (Beacon Press) Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision by Barbara Ransby (University of North Carolina Press) Freedom’s Teacher: The Life of Septima Clark by Katherine Mellen Charron (University of North Carolina Press) Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC edited by Faith S. Holsaert, Martha Prescod Norman Noonan, Judy Richardson, Betty Garman Robinson, Jean Smith Young, and Dorothy M. Zellner (University of Illinois Press) Let It Shine: Stories of Black Women Freedom Fighters by Andrea Davis Pinkney (Harcourt) The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks: Young Readers Edition by Jeanne Theoharis and Brandy Colbert (Beacon Press) Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All by Martha S. Jones (Basic Books) |

Related Articles and Resources

|

Audley “Queen Mother” Moore Interview, 1985 (YouTube video) “Audley Moore, Black Women’s Activism, and Nationalist Politics” by Keisha N. Blain (Black Perspectives) “Queen Mother Moore: Matriarch of the Captive African Nation” by Akinyele Umoja (Black Perspectives) |

This Day In History

|

May 6, 1922: Gloria Richardson Born Sept. 29, 1951: “A Call to Negro Women” Sojourners for Truth and Justice Aug. 8, 1964: Freedom Schools Convention Oct. 15, 1966: The Black Panther Party Founded July 1, 1970: The Lincoln Pediatric Collective Forms to Serve Bronx Community May 27, 1972: First African Liberation Day Demonstration on the National Mall Aug. 15: 1975: Joan Little Acquitted June 27, 2015: Bree Newsome Removes Confederate Flag |

Participant Reflections

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

The most important thing I learned today was Queen Mother Moore’s relentless support of Black Nationalism during the height of the Civil Rights Movement, highlighting the breadth of the Black Freedom Movement.

Her depth, her relations with many different people in the Black Freedom Movement (no matter the “side”), her gender politics — just the full force of who she was. I did not know very much at all prior to this.

Talking to students about how we collectively remember the past, and examining who has the power to tell and erase parts of history.

Queen Mother Moore was empowering women while upholding her own gender politics. Rosa Parks and Mother Moore sat in similar spaces and places.

The piece of information that touched me the most — because of my own experiences being surveilled for advocating for Black students — was learning how heavily surveilled Mother Moore was and the fact that she went to the FBI herself to tell them to leave her alone. It touched my spirit and I will carry this information with me forever!

What will you do with what you learned?

I’m going to look for ways to integrate the teaching of reparations and freedom dreaming in my lessons.

Including the content of unsung heroes like Queen Moore and exercises that give students the critical skills to unpack the dominant narratives are things I’ll take up in my classroom.

With the knowledge I’ve gained I’m going to use a space in the school library to highlight Queen Mother Moore and I’d love to create a list of resources for students, staff, and families to look at once I do my own research.

I will continue to learn about “controversial” figures, and include their stories as ones worthy of telling, even if the story is complex. Including these names and narratives is critical for expanding awareness in our children, that other possibilities for how to be have and still do exist.

I will be working to incorporate these resources into my curriculum. Additionally, I loved the insight of historical people not being heroes. Instead they are people who had a set of choices and chose the admirable ones.

Presenters

Ashley Farmer is an associate professor in the Departments of History and African and African Diaspora Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. Her book, Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era, is a comprehensive study of Black women’s intellectual production and activism in the Black Power era. She is also the co-editor of New Perspectives on the Black Intellectual Tradition, an anthology that examines central themes within the Black intellectual tradition. Her forthcoming book is Queen Mother Audley Moore: Mother of Black Nationalism.

Cierra Kaler-Jones is a social justice educator, writer, and researcher based in Washington, D.C. Her research explores how Black girls use arts-based practices as mechanisms for identity construction and resistance. She is the director of storytelling at the Communities for Just Schools Fund.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn