In the face of increased attacks on teaching honestly about history, LGBTQ identity, the climate, and more — teachers need each other. In many states, unions or a sympathetic school district administration provide support.

But in others, teachers face laws and threats alone. Here is what we hear from teachers working in isolation.

We have educators unable to fulfill Black history month plans due to the lack of diversity in books and due to new laws and regulations on what they can and cannot read.

I’m terrified to say anything about enslavement because it might make students “uncomfortable.” I also can’t recommend ANY books because a parent might not like it and then I could be charged with a felony.

Books are being removed from our media center and I can no longer use certain resources (ex. 1619 Project) in my curriculum as a U.S. History teacher.

They would not let me teach Just Mercy by Bryan Stevenson for the past two years.

I had to remove my “protect trans kids” poster from my classroom wall.

We are not allowed to say social emotional learning because it’s “tied to CRT.”

It is creating a chilling effect on education. We continue to teach the truth, but with much less certainty what the consequences will be for doing so.

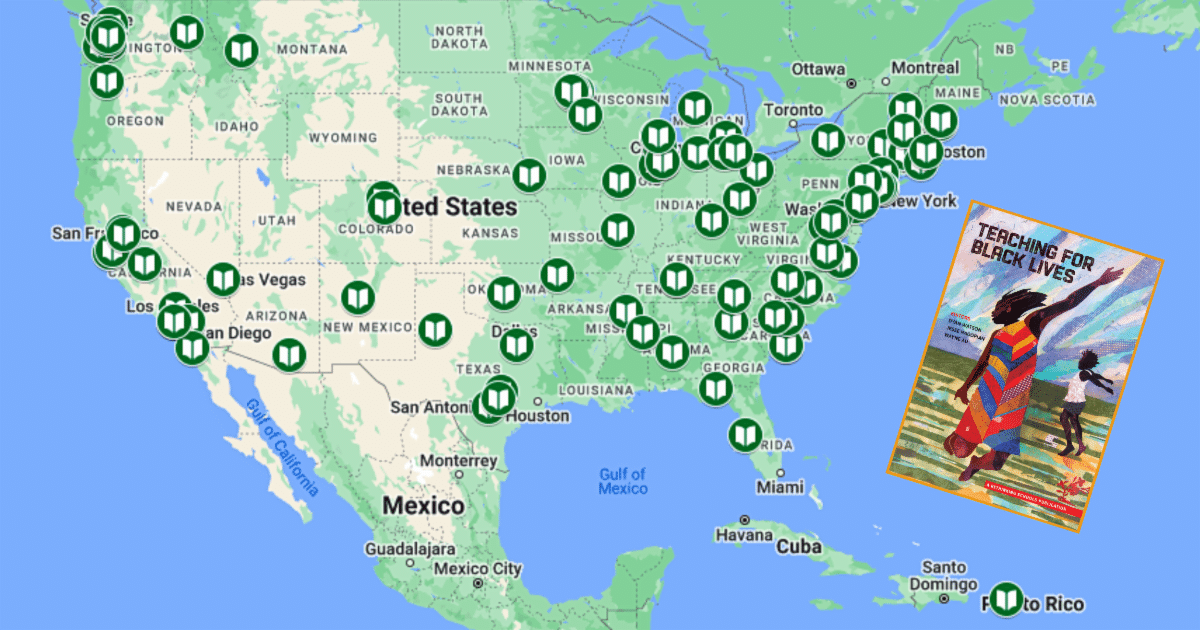

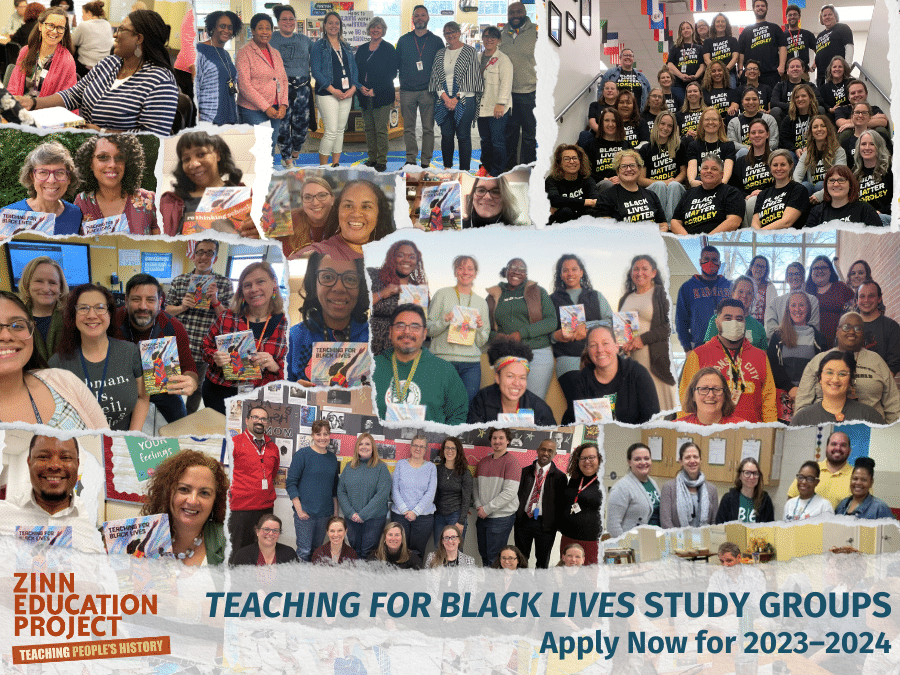

Three years ago we launched Teaching for Black Lives study groups in schools around the country. They provide teachers support, resources, and encouragement to teach young people honestly about systemic racism and how to organize for justice.

Educators join a national network of teachers, school librarians, counselors, administrators, and school staff who are defying efforts to ban what students can learn in school by vowing to teach for Black lives.

Educators report that the study groups not only deepen their knowledge and improve their practice — they also increase their resolve to continue teaching honestly. And they provide a community of accountability and mutual support.

These groups also challenge the mainstream media’s recent narrative that after the historic uprisings of 2020, everyday people’s commitment to combat racism and white supremacy is waning. Not only have these educators sustained the antiracist work taken up by so many in 2020, they have deepened and expanded it. That is what the right wing is trying to suppress. And that is what the study groups nurture.

Here is what study group members tell us.

It was one of the few things I took on this year that added to my resilience, to my sense of community, to my energy to keep going and do the work. The support that came as we worked together was and is invaluable.

Being a part of this group was the best part of my school year. I was constantly inspired by the people I met around the country and the work that they are doing to bring the real history into their classrooms despite insurmountable challenges. I cannot recommend this group more!

It is a powerful community to be a part of! When thinking about where I find encouragement in an already tough job, it is with this group!

Sometimes it feels like it is time to hang it up and do something else. Then you remember if not me then who? We must serve as the light to pass the light to others so that our progress forward is reinforced by other generations of educators.

Having a reliable and deeply thoughtful group of allies in my community was so powerful and supportive during this difficult year. I drew strength every day at school knowing that my study group colleagues were there and would be supportive of my practices.

The group context gave us courage to stand in spite of the climate.

Our group was fueled to do more, be more vocal and active to fight against the current political climate because we are all in for all kids every single day.

This study group provided a safe space to confront the injustice in our school and allowed our staff to have open discussion about some tough issues.

We read together, discussed difficult topics, problem solved, shared insecurities, challenges, struggles, and hope. We held each other accountable and held each other up.

We would commit to trying new lessons, facilitating restorative circles, facilitating difficult discussions with colleagues or with our students and then come back and report to the group. It was motivating knowing that the group would be there to process the results together when we met.

It’s easy to get stuck in the learning and reading phase without actually turning that new knowledge into action. This group held me accountable to actually doing something that would make a noticeable change.

I have a new lens to look not only at my interactions with students and colleagues and community but at our larger school system and district ALL THE TIME. I feel empowered with all of the resources we have to find another approach or way into whatever we are doing in class. Now my students know that if I am wearing my BLM shirt or Black History Matters shirt at school it is not a performative act — it means that they can hold me accountable to what I have done in and out of class to show that I am living up to that belief.

What we love about all the chapters in Teaching for Black Lives is that each lesson shows the “how” of teaching for Black lives. Once participants begin recognizing that white supremacy impacts all of us, the natural question is what do we do about it. And the book shows, over and over again, chapter to chapter, ways that teachers are teaching for Black lives. This is the how! So the book is not just about re-learning history (the content), but also the practice, the instructional strategies that readers can take or take and modify for their own use.

These past three school years, the list of burdens educators have had to confront is long and heartbreaking. A pandemic that killed more than a million people in the United States — including family members, students, and colleagues — and is ongoing; critically understaffed schools, requiring the juggling of an impossible number of responsibilities, all while forgoing planning time and lunch and bathroom breaks; the accumulated social stressors of the last three years manifesting in children’s needs for more support of all kinds; all too frequent school shootings; and ongoing rightwing attacks on teaching an honest account of white supremacy in the past and present, and on LGBTQ+ youth.

And yet we have witnessed a remarkable demonstration of educators’ commitment to build more just schools. Through the 100 Teaching for Black Lives study groups in 30 states, more than a thousand educators are coming together to learn, support one another, and take action. Let’s triple the number of study groups for the next school year. Teachers need the support and solidarity.

Donate

Make a gift through the Zinn Education Project today and indicate your contribution is for the Teaching for Black Lives study groups.

Start a Study Group

If you and colleagues are interested in forming a study group, learn more and apply for the 2024–2025 school year.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn