On January 23, 2023, we hosted historian Dayo Gore in conversation with Jesse Hagopian to discuss Black women radicals who were active during the Red Scare. As one participant shared during the event, “Black women are the engine of change — were, are, and will be.”

This session was part of our monthly Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online class series. Don’t miss the 2023 lineup — register now.

This session was part of our monthly Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online class series. Don’t miss the 2023 lineup — register now.

Participants shared what they learned and additional reflections on the session:

The most important idea is that there were not just a few Black women leaders in our history, there were many. And we need to bring them up to the surface for all to see, learn from, and recognize. If we don’t then we are saying that they don’t exist.

I was most impacted by the roster of Black women radicals mentioned and the depth and breadth of their intellectual and political organizing despite the constellation of obstructions they faced during the era of McCarthyism.

Tonight had me considering the ways in which women’s, specifically Black women’s, contributions to movements are too often down-graded or overlooked. The view of being a helper versus a creator, a follower versus a leader, is central to how people are viewed. Tonight’s session reminded me to look for the leaders and changers in those around me that may be being pushed into the background and to help propel their voices and ideas to the forefront.

It’s powerful to learn about the buffet of organizing tactics Black radical women during the era used: due process/legal tactics, direct action, using the media, etc.

I will use these stories to empower my youth to be great thinkers for social change.

Thoughtfully organized — Dr. Gore’s speaking was riveting and I wanted to re-enroll in college at age 55 to re-engage my history learning at this level all over again!

The theoretical work that radical Black women did in the 1950s with the Communist Party did not die with McCarthyism — they carried it on in other organizations and by other means!

There is so much to process but the most important thing was to be active, show up to these school board meetings, and fight for educational rights! I learned about some new stories that I am eager to research and read about. I will be purchasing the recommended books. I am extremely grateful for this resource and tonight’s session.

I have been to many sessions and I do enjoy the time when we spend with others to help connect our learning. I greatly appreciate all of the presenters that have shared with us.

Event Recording

Recording of the full session, except for the breakout rooms.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: We’re going be talking about So You Want to Start a Revolution? Black Women Radicals Confront the Red Scare with Dr. Dayo Gore. We have a great program for you today. Some of you all are joining us for the first time, and I bet a lot of you have participated ever since we launched this series back in 2020. Jeanne Theoharis came to the Zinn Education Project and proposed this idea, and we’ve been running with it ever since. So it’s really a gift to be able to share this time together. Thank you all so much for being in this virtual community with us month after month in the struggle.

Today’s class is hosted by the Zinn Education Project, which is coordinated by Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change, and this is all part of the Teaching for Black Lives campaign that you can find at teachingforblacklives.org. We have members here from our Teaching for Black Lives study groups. We have close to 100 study groups around the country that are reading Teaching for Black Lives and implementing it. So, if you’re in one of those groups, please add T4BL after your name. Also, I just want to let people know that we offer free downloadable people’s history lessons that many of you have used for middle and high school classrooms at the Zinn Education Project website, including some directly relevant to tonight’s session. There’s one lesson called Subversives, [that] I would highly recommend everybody use in the classroom. This will definitely give your students a new perspective on our country. I’m also very glad that we are joined today by ASL interpreters, Krystal Butler and Tierra Carter, thank you both for being here, much appreciated [for making] this accessible.

Before we begin our conversation, we want to find out who’s in the room and go through our plans for our time together. So, we are posting a quick poll to find out how many teachers are with us, how many librarians, teacher educators, historians, parents, students, any other kind of educator who’s with us today. If you’re in multiple roles, just pick a primary one, and let’s find out all the different parts of the education system that we are going to overhaul and remake. All right, those numbers are streaming in. It looks like we have about 40% K–12 teachers, 2% students, 2% family members of a student, 16% teacher educators, 7% historians, and 3% librarians. So glad librarians are with us — they are facing a specific threat as well. In this era of banned books, it’s so important that we dig into important books like we will get to tonight.

But before we begin, I just want to let people know that throughout the session, we want to invite you all to use the chat box so you can post questions, comments, resources, ideas,. And we’ll do a short evaluation at the end of this session. So, be sure you fill out the evaluation form before you leave. Also tweet what you’re learning. If there’s something that you didn’t know — and I guarantee there will be something that you didn’t know in this session — please tweet it out and let other folks know what you’re learning and that they should be part of these monthly classes. After about 25 minutes, we’re going to pause the discussion and you all will get to meet each other in small groups and share your thoughts and talk about how you’re going to put into action what you’ve learned. So, with that I am very happy to welcome Dayo Gore, associate professor in the Department of African American Studies at Georgetown University, author of Radicalism at the Crossroads: African American Women Activists in the Cold War — everybody needs to get this book, it’s highly recommended — and also co-editor of You Want to Start a Revolution? Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle, co-edited with Jeanne Theoharis and Komozi Woodard. Thank you so much for being with us, Dr. Dayo Gore.

Dayo Gore: Hi, it’s a real pleasure to join you. Thank you all for joining on Zoom on a late evening, I’m sure after a busy day. I’m excited that people are here. You know, historians don’t often get a chance to share their work with large crowds except the students that are forced to attend. So, I’m excited to see so many interested thinkers here, and teachers here, to hear me talk about my work.

Hagopian: Yes, we are all very excited as well. I learned so much from reading your works over the last couple months. Thank you so much for writing this invaluable book, and greatly expanding my understanding of Black women’s contributions to the communist movement, the feminist movement, the Black Freedom Movement. I was just thinking over all that I was learning and I just wanted to thank you specifically for introducing me to Vicki Garvin. I guess I had read her name in a couple of books that I went back and looked at, but it didn’t stick with me, and this time I think I really got a new understanding of the American labor movement and the feminist movement by learning her story. So that was particularly a treat. But we don’t really learn about the Communist Party very often in school. In fact, Florida has a day now where you have to teach the horrors of communism. [There’s] no day prescribed that you have to teach the horrors of capitalism. But that’s the kind of red-baiting that we have back in our schools today. But the Communist Party was a major force in the struggle for Black liberation in the 1930s and onward. The CP was approaching 10,000 Black members, almost ten percent of the party. That was just staggering to me, when I first started digging into that history and learning that. I had read some about Black women in the Communist Party, but we certainly don’t learn that in schools. I’d read mostly about Claudia Jones, who is an incredible figure that I’ve learned a lot from, but so many of the others that you write about were absent from even my radical education outside of my K–12 education. You write compellingly about the different things that specifically brought Black women into the Communist Party, like the Scottsboro Boys case, the struggle for a decent education, workers’ rights campaigns, and specifically struggles for Black women workers. So I’m hoping you could talk about what drew Black women like Thelma Dale Perkins, Claudia Jones, Marvel Cooke, [and] Vicki Garvin to the Communist Party.

Gore: Oh, thank you so much. Thank you for that lovely introduction, and for spending some time with my work. It’s really a pleasure to talk to someone who’s spent some time with the work and found it exciting. It’s always nice to hear. And particularly Vicki Garvin. I’ll just say Vicki Garvin was one of my key people that I connected with. I was able to interview her. I was able to interview her daughter, [and] family members afterwards. They’ve been very supportive of the work I’ve done. I don’t know if you know, a lot of her archives are at the Freedom Archives, which is a great collection based in Berkeley, online. I used to have phone calls with her; she would call me and send me little notes as I was doing this work. So I felt really tied to her. I actually got introduced to Vicki Garvan earlier because she had written in a magazine that I had been studying from and I thought this really was an interesting piece. Then I went back after I met her and I was like, “Oh, this piece was by Vicki Garvin. I didn’t know she was still active for quite a while.” So I’m glad that she stuck with you. She has stuck with me as one of the key figures.

And I think you’re correct to say that we don’t often hear the stories of Black women on the left, in the Communist Party. In part because I think they get marginalized if they’re not seen as the clear leadership, or what we expect leaders to look like. Because many of these women — Vicki Garvin, Thelma Dale [Perkins] — were heads of organizations, powerful theoreticians thinking critically about race and gender. So they were doing that work, but also doing the daily organizing work. I think we rarely think of Black women wearing all those hats, or recognize all those hats they can wear. So, when I started, I’ll just say, I started reading Freedom newspaper, which is a Paul Robeson newspaper that came out in the 50s. He along with [W. E. B.] Du Bois and Shirley Graham Du Bois came together and decided to do this newspaper. When I started reading it most of the bylines were Black women — Thelma Dale [Perkins], Vicki Garvin, Lorraine Hansberry, Alice Childress. Women I had known. I grew up reading Alice Childress’s books and watching films based on her books. And it was a surprising moment to me to think about these figures that I, as a historian, had been interested in showing up in this place I didn’t expect them.

I think that’s one of the powerful stories that I try to tell is that it’s not just that we need to include these women in the left or pay attention to Black women as a part of this membership in the party, but we need to think about how their presence alters what we think about is possible in the left; how we envision freedom and Black freedom; how we think about feminist politics. Because they’re thinking about all these issues, and if we don’t include their voices, then it gets lost in a history of the left. We think of a left that doesn’t have these politics, and I think these women do. I think in part what I love about this book — in doing this work and writing it — is that I got to see what drew them to the Party.

Say Vicki Garvin, for example, [who] was active in the labor movement, went to Smith College and did her master’s on questions around labor and economics, had worked in the federal government during World War II and became interested in race and gender and labor, and [who] joined the Party actually in ‘47, almost at the height of McCarthyism. I think because of its politics, yes. She was looking for someone who could have a critique of capitalism that she was seeing in her work. You could see it developing in her master’s thesis that she wrote at Smith. You can see her thinking about it, as she writes about the labor work she’s doing during the war, and how African Americans — and particularly African American women — are being sidelined out of the labor force. But I also think it allowed her space to also be herself. That wasn’t so much the Communist Party, right. I do think the party struggled continuously with how to create a culture and a politics that recognized and centered race and also welcomed Black cultural expression in a real way. But I think she saw other activists there, and other people who were willing to engage the issues she was taking up. And it also allowed her — and I think she’s emblematic of a number of women — a space to do the work she wanted to do. Maybe not always on her terms, but a way to sort of have debates and engagements and political work she wanted to do, for paid work even, through her membership in the party, through her affiliation with some of its offshoot organizations.

I think the last thing I’ll say they found particularly, I look at a group of women who end up in New York in the ‘40s, around Paul Robeson, Du Bois, a number of leftists that come to New York in the ‘40s as the Red Scare and anti-communism is making it difficult to organize in the South or smaller cities, and what they find is a community. So, I do note that a lot of the women have this politics they develop in the 30s, they’re a part of this movement of activists who are experiencing the Great Depression, looking for answers, and the Communist Party provides some of that. But when they land in New York in the 40s, they find a community, or they’ve been invited into a community. So figures like Thelma Dale Perkins, who I write about, is organizing in D.C. She actually grows up in Anacostia, and in ‘43, she comes under suspicion for her work in youth organizing in D.C. They invite her to come to New York and take up a position working with the National Negro Congress. So they bring her up to New York as a way to support her when she’s finally coming under attack. Or someone like Beulah Richardson, who’s probably more well known as Beah Richards, is in California doing poetry and performing, and she is invited to come to New York by William Patterson — who is one of the key Black leaders in the Communist Party at the time — because of her poem she’s writing and to be a part of this collective. So I also think it’s the politics. I mean, who doesn’t want to be in New York? But it’s also, I think, the collective community. Thelma Dale [Perkins] has this great quote. When I interviewed her, she said, “It was the people.” She was like, “I studied Marxism [but it] wasn’t the thing that I spent the most time on. But I’ve studied what I needed to study.” She’s like, “But it was the people that attracted me, the right people, the people doing the work I wanted to do.” And I think that is a key moment for this generation who ends up in New York in the 40s and 50s, doing such important work.

Hagopian: Yeah, the synergy between them was just palpable when I was reading this. Just seeing the way they built on each other’s theories and practice, and pushed the Party in different directions because of their relentless organizing. Black women played such an important role in changing the culture of the Communist Party in the 1930s. I really liked this quote that you use from Louise Thompson Patterson, that she made in the CP’s internal paper that they should take more of a human approach to recruiting Black women to the party. And you quote her in the book saying, quote, “For example, I think that often when we have affairs, dances, etc., if we went around we would find young Negro girls who would be glad to attend if they got there and found out they were given consideration, danced with, not made wallflowers. We would find that these are the things that count, these are the things that hold a lot of Negro women back from the Party.” She’s really strategizing about how do we build an inclusive culture that sees Black women in the Party to the point where they’re invited to dance. Elsewhere I read that at one point they even did implement dance lessons for their white members so that they could interact with Black women, and not just leave them out of events. So, I think that she clearly had that influence, but I was hoping you could talk about what Black women’s lives were like in the Communist Party, and how they changed the culture of the Party.

Gore: That’s it. I didn’t know at this point about dance lessons. I don’t know that it helped. I mean, it’s interesting to note, she’s writing in the 1930s, and she’s one of the early Black women who are in the Party. She joins, Maude White [Katz] joins the Party very early on, and they are some of the first people to struggle with whiteness and white supremacy. This shapes the culture of the Party, which is very real. But we see this as a continual question that comes up. Even Claudia Jones was writing in the 50s when she writes her groundbreaking piece, “An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman!” that she raises this question not about dancing, but you can’t think that every Black woman you see at the party can be your mate, like that’s a way to engage them. Or you can’t always think of them as somehow not at the same level as you, and you can’t think about their issues as simply a different variation of your own. So, she raises all these questions in the Party, so it clearly isn’t resolved.

But Louise Thompson Patterson’s quote is ongoing, this question about how you create a culture that’s welcoming in a sort of racist and sexist society, right? And people bring those practices to them, and then a Party that struggles with how they think about not just class difference, but how it intersects with racial difference, gender, things like sexuality, right? The Party has a long history of struggling with those things, and I don’t think we should gloss over those real struggles. In part, I think that’s what Black women are able to do through a collective effort. You can see a number of them operating in different ways to try to articulate and create space for Black women in the Party. Some of it is pushing the Party to think more theoretically about these issues and to include race and gender — and the experiences of particularly Black women at those intersections —in their theorizing about the end of the war, about class politics, about the labor movement. And there are real struggles around it, that they began to see civil rights not just as a Black Nationalist issue, but one that might have a profound impact on everyone in the United States. Or that they see Black women’s leadership as one of the central things they should take up to move forward not just the Black community, but the left more broadly.

I think Thelma Dale [Perkins] writes pieces about this, Claudia Jones, Marvel Cooke mobilizes around this. Vicki Garvin writes a lot about this, particularly in terms of labor. But I think what they are able to do, in some ways, is take a multi-pronged approach to try to create space for other Black women and attract other Black leftists to the Party and see the value of that, and to also push the Party to address some of these limits. And they do it in a number of ways. My book talks about Louise Thompson Patterson’s work, Claudia Jones’s work, but also some of the theoretical work they do with other white women around thinking about gender at the intersections of race. I quote a lot from Buelah Richardson’s poetry, which theorizes how we might feel solidarity that does not erase difference. So I think they take a multi-pronged approach. But also, I’ll just say, I think they continue to be frustrated. So, at the end of the chapter on Vicki Garvin, she is sort of frustrated with the Party’s inability to see some of what the National Negro Labor Council is doing, or other organizations as powerful, even as things like the Civil Rights Movement are taking off, and she’s sort of frustrated that they’re not willing to hold this line and continue with these politics. That they’re going to move in a different direction. I think it’s a continuous struggle, but a struggle they’re invested in, I think, because they find some value in the spaces that the Party supports, and the politics and theorizing that the Party does. Also, it creates a real space to take seriously, I think, the questions of Black inequality and white supremacy in the U.S.

Hagopian: Yeah, thank you for that. I really like how you paint a picture of how Black women struggled to be seen, and to have their theoretical contributions understood and then carried out in the Party, while also understanding that the problems of racism and sexism weren’t unique to the Party. That these are problems in the broader society that are brought in by the human beings that made the Party, and then it’s how do we make the Party actually fight for human liberation in all its intersectional forms. This the great contribution that these women made. I was hoping that you could talk more about how these Black women’s contributions to social movements and the Black Freedom Struggle are often minimized or invisibilized.

When Black women are considered, it’s often for the work they’ve performed in the day-to-day struggle, the tasks that they’ve carried out in the organization of the social movements. And these tasks have often been taken up by women and are critical to the functioning of any organization and social movement. But to limit our understanding of the Communist Party, of the Black Freedom Struggle in general, to those tasks, I think, is to make invisible their theoretical contributions to understanding how we get free, and how everybody can get free. Your book is such a great corrective to this problem. We learn about Claudia Jones and other Black women who built theoretical foundations for what today we would call intersectionality. So, I’m hoping you could talk about those theoretical contributions of Black women radicals in the 30s, 40s, and 50s.

Gore: I’d love to. But I guess I would say that part of my thinking about this is really built upon a lot of work that came before, scholars thinking about Black women, and a whole range of scholars before me who really thought about Black women’s history in this context. I think about some of these: Tara Hunter, Elsa Barkley Brown, that really tried to center Black women’s lived experience. I think about my work, the anthology I did with Jeanne Theoharis, and her biography of Rosa Parks — it really had us think differently about Rosa Parks. So I feel like in part, my work is focused on the left, but drawing on a lot of that other work, and also some of the early work that was done in the Civil Rights Movement that did talk about women as grassroots organizers. And I think, unfortunately, that has become sort of the lane they’ve been given — you know, the women are in the pews and the preachers are on the stage, kind of framework. I think, in my work, and building on the work that had come before me, I wanted to try to think about what does it mean if we think about leadership that can both do the organizing on the ground things, but also that organizing is built on a theoretical framework and, in addition to that, have leadership roles? How do we think about that as a part of the movement? Because I think, even in our broader understanding of movements, we often think about the foot soldiers and the leaders, and I think that’s a sparsity of frameworks, that we can’t think about how people move through many different iterations, depending on the movement, depending on the needs of the moment, depending on their skill set. And I really want to be attentive to that, and also to be attentive . . . I think one of the reasons that Black women often get seen as not theoretical, not contributing, is because they don’t have the great book. If you aren’t able to make the great book, then how do your theoretical contributions get read? I would encourage us to be more creative in how we think about the ways people put out their ideas.

So what I tried to do was really look at the journals of the Communist Party, where these theoretical debates were happening, look at their organizing, not just as a grassroots movement, but as built around a political vision, built around their theorizing of how change happens, built around where they see key investments for creating strategic advancements in the Black community, or around the issues they were struggling with. So I think, in part, when you look at that you see some really important things, and to look at other sites. So, I think something like Beulah Richardson’s poetry is a powerful theorization of intersectionality, of ideas about bodily autonomy, ideas about how we might think about racialized sexism and sexualized violence. That she articulates all of these things through poetry, I think, is quite impressive. Also through her organizing. But that’s what we get left, those two things, that was her skill set. So I look at some of their work, the ways in which they organize around certain campaigns, to try to center their experiences, in some ways to push for thinking about the ways in which even before we see the ideas of double jeopardy, or intersectionality, they’re talking about the ways that Black women experienced race, gender, and class, as domestic workers in the workforce, how the structures of economics shape their gendered experiences. They’re delving into all those issues in a number of ways.

I think most popularly we see it — I guess I shouldn’t say popularly, because I don’t actually think Claudia Jones circulated in a popular way — but I think probably the most familiar person is Claudia Jones, who does this, I think because of her later history in London, I think she has a broader reach. But other figures like Thelma Dale [Perkins] are writing about this, though, and is one of the first people to really push and shove Charlotta Bass to run as vice president in 1952 on the progressive ticket, because she says, “We really need to think about centering Black women’s leadership.” Charlotta Bass had been such an active force in the Black female struggles, and early on she becomes an active campaign manager for that. You see women thinking about the ways in which we need to think about gender and race globally. How do we think about it in African diasporic solidarity not just through race, but also how gender travels in those spaces. So, I think they’re contributing a lot of different, complex ways of theorizing that sees identity not as a problem, but as a source of power. That theorizes if we can build an analysis that takes up these questions, and can think about how we mobilize people around them, we can have a broader reach. In part, they’re doing it in the 40s and 50s, when the terms of debate are so much about what will happen around the family — these moments when you see the rise in the almost homophile movement, where you see questions around what woman ought to be and do, where you see questions around, obviously, African American experiences, the limits of American democracy because of segregation, and these other questions. And they’re able to step into that conversation and link a lot of those ideas and debates, and intervene and have their own perspective on it, because they are able to talk about all of those things — race, gender, class, sexuality in this moment, and give an analysis that is both historical, looking back, but also trying to imagine a different future.

Hagopian: Yes, thank you for breaking that down. I just think that’s so critical for understanding the moment that we’re in right now because our schools are under attack all across the country, education is under attack, certainly because of race, because they just banned AP African American history. They’ve been going around saying, “No, we just want to ban critical race theory. You can teach about slavery still, or you can teach about Black history.” But now their true motives have been revealed. If you weren’t sure already, it’s clear now that it’s really about banning any discussion about Black history and Black Freedom Struggles.

But it’s not just racism that we’re facing. I mean, look at what’s happening to trans kids right now. Trans families are being made illegal in states around the country. The “Don’t Say Gay” law in Florida [for example]. This is really an intersectional fight that we have to lead. We have to figure out how we link up the struggle against racism, sexism, homophobia, if we’re going to push back [against] this anti-truth, anti-history attack. I think there’s just so many lessons in your book for the moment where we’re at today, because these Black women in the Communist Party were organizing during the era of McCarthyism, when there was just such immense repression. And one of the things that I’ve come to appreciate, I think I’ve rethought a little bit about what I understood about McCarthyism, because I didn’t realize the degree to which Black women created space for struggle, I think, because their stories had been left out as so much of what I learned. So, I’m wondering if you can talk about what we can learn from these Black women radicals during the McCarthy era, that is increasingly looking like what we’re going through today, so that we can learn how to struggle against this neo-McCarthyism that we’re facing.

Gore: Yeah, I mean, we were chatting a little bit earlier. And I have to say, I do feel like this moment feels almost more extreme in some ways, because it’s so blatant. There isn’t a subtext of anti-communism. They are anti-communists, obviously, I was just reading some things about this, but also, it’s very clear that some of the things they take up, Critical Race Theory, the idea is that you think about oppression and the ways in which white supremacy might give privilege and oppress others that that is out of bounds, that we don’t want to know that history, even if it’s so foundational to the country, and ongoing. I do think it is, in some ways, a more explicit moment. But I think that also makes it clear what the challenge is. And I think in McCarthyism, it was an interesting moment because much of the push back against Black civil rights and Black liberation activists or people in the Black Freedom Struggle was simply to not articulate any support for communists, or people seen as left, or people who are thinking about the world. But that list kept getting a little more sort of expanded, right? “We’re not against Black civil rights, we’re against these things.” But it made it more difficult to organize and still stay on the good side of the anti-communist policing that was happening. If you were to meet the demands of the state, it really narrowed the framework you could operate in. And we see that happening in a number of organizations. The NAACP is one of them where their mission gets really truncated and many people who have been involved on the left decide to leave. Even affiliated things like the Council of African Affairs, Mary McLeod Bethune was in that organization with Paul Robeson, and left because she feels that it is going to mark her as a communist. So, even things that weren’t necessarily engaged with the Communist Party became banned. And I think that is the force of these practices: that you start to police yourself, you start to fear doing anything. And that is real. I mean, I don’t want to diminish what McCarthyism did — it cost people jobs, it policed people heavily. I think for Black women, one of the biggest costs was that they lost these employment opportunities. Many of them talk about organizations that were shut down. People couldn’t teach. People were ostracized from their communities.

I don’t want to imagine that Black women didn’t experience that. Obviously, Claudia Jones is a figure in this moment. She gets deported to London, they tried to send her back to the Caribbean, but she ends up going back to London for her work in the Communist Party. She at one point is the highest ranking Black woman in the Communist Party. So they do have real impact. Esther Cooper Jackson talks about the impact it has on her family when her husband has to go underground. So people who do have real impact are carrying the brunt of McCarthyism in this moment. They don’t emerge unscathed. But I think what they are able to do is, in the spaces that exist, they are able to build a collective space for Black women. So, it was surprising for me to see things like Freedom newspaper, Sojourners for Truth and Justice, the Civil Rights Congress, with a lot of Black women’s leadership in it. The work that Thelma Dale is doing in the Congress of American Women until it gets closed down, and that these women continue to mobilize, even in the 50s. [Vicki] Garvan ends up going to Ghana and then China, when her options in the National Negro Labor Council, which emerges in the 50s, get closed down. So, I think it’s an interesting moment to see where, in this space of attack, Black women, and the Black left more broadly, are able to create organizations that they envision, that in this moment of downturn, they claim a space and step into leadership to create these important organizations.

But it’s not a happy ending. It’s not like the organizations sustained for long periods of time, but they do create an important legacy, and I think guideposts for the Civil Rights Movement, and even for activists in the 60s and 70s to follow. I think also, they allow these women to build a collective community that sustains after this. I think one of the things we miss when we don’t look at Black women’s organizing is that we focus on the organizations, and we say, “Oh, the 50s are clear, all these organizations are closed.” But actually, when you follow Black women, or even Black leftists, you see they are able to move in different spaces and still carry their politics out — not unconstrained, not without having to negotiate some things — but they’re able to do that in really important ways.

The other thing I argue in my book is that basically no one expects Black women to be in positions of leadership. So, it takes them a while to catch up. I love Barbara Ransby, [who] has this great book on Ella Baker. I love where she talks about the FBI file, where they can’t figure out if Ella Baker is married or not — like they don’t have the wherewithal to understand what’s happening with their home life. I do feel like the government is not all knowing, and in some ways they aren’t able to really track [everything]. If you look at some of the FBI records that I looked at what’s happening with these women — Are they in the party? Are they leadership? What are they doing? This can’t be possible. Why are they here? And so I think some of that is powerful. But I think the main thing that allows them to sustain — and it’s partly shaped that I’m looking at people in New York — is that they’re in a collective space together. Beulah Richardson, I think in my last chapter, has this really powerful quote where she’s having this resurgence in the 70s, because her work is such a feminist clarion call, in some ways, particularly her “A Black Woman Speaks,” and she’s like, “it’s exciting, but it’s not the same as it was before. I don’t have that same closeness that we did in the 50s.” As in the left. And that she could think about that moment as a powerful moment in her life, I think, really speaks to what collective power — even in the face of government assault, of neighbors turning on you, or you losing your job — can provide.

Hagopian: Thank you so much. What a rich conversation. There’s so much for teachers now to chew on. Alright, y’all, let’s get back to some more questions. But before the questions, we want you to get involved in your local school board, and attend meetings, testify, and run for office too, because we need y’all to defend the teaching of people’s history. It’s under attack in state after state and district after district. We just want you to consider ways that you can join the struggle to defend this history. One way is to donate to the Zinn Education Project. We continue to offer these classes and give away these lessons for free, but we need support from the community to continue to do this work. So thank you for that consideration as well.

We’ve got time for some more questions. I hope you’ll stay with us all until the end. If you all have questions, we want to get to those too. I have a few more. There’s just so much in this book I want to ask you about. We probably won’t get to it all. But I’ll start off and then maybe we’ll find one from our audience. I’m really fascinated by your discussion of the 1948 case of Rosa Lee Ingram. realized I’d read that name in passing, but I didn’t really understand the significance of that struggle. She was a Black woman who was sentenced to the death penalty along with her two boys for defending herself against a white man who was trying to sexually assault her, and she ends up killing him. I’m fascinated by how Black women communists and radicals rallied around her case and what it says about the role of Black women to continue the struggle for radical justice, even under the most inhospitable conditions of McCarthyism. You quote the CRC’s internal discussion of the case saying that, “Negro women throughout the land stand ready to make Mrs. Ingram’s freedom their own cause.” I’ve read many times about the Scottsboro Boys that were such an impetus to radical struggle, and I think the Communist Party’s campaign around the Scottsboro Boys was incredible, often when the NAACP was slow to get involved, and they were actually taking up that anti-racist campaign. I’ve long been inspired by that work of the Communist Party, but I hadn’t really appreciated Ingram’s case. As you point out, the case provided a powerful challenge to long-established assumptions within the African American community also about who victims were. I think similarly to the way we see the victims of state violence today being men all too often and the women victims have been sidelined. Hence the necessity for the Say Her Name campaign. This was the work that communist women were doing at that time. So, I was hoping you could talk about what the Ingram case was and what it reveals about Black civil rights activism during the McCarthy era.

Gore: Absolutely. Thanks for the questions. These are great questions. And this is one of my favorite chapters to talk about, because in some ways it encapsulates a lot of the work that the women are doing. I think, in part, it’s really important to think about their work on multiple levels around this case. So one, a number of the women are involved in the We Charge Genocide petition that comes out in 1951, that’s issued by the Civil Rights Congress. What they’re doing to build that, they’re working on a lot of civil rights cases at this moment, both around Black men who are accused of raping white women who then gets sentenced to death, and then around cases like the Rosa Lee Ingram case. They end up traveling to these places to speak with the families, to investigate. Similar to Ida B. Wells in her anti-lynching campaign. One of the women that travels to Georgia to meet with the family is Yvonne Gregory, and she goes out there to meet with Ingram and her family to investigate the case. It gets included as one of their key campaigns, but it also gets included as part of the evidence that they mobilize for when they put out the We Charge Genocide campaign. This case became so central to Black women. It is the case that inspires Black women like Lorraine Hansberry, Beulah Richardson, Claudia Jones to form Sojourners for Truth and Justice as a Black women’s civil rights organization.

At its moment it really highlights in part the larger struggle they’re having, that they’re trying to defend Black people who were suffering under the carceral state, and particularly the ways in which Black people who were accused of things are getting convicted in high numbers with very little judicial justice involved at all. The Ingram case becomes a space that speaks about that, but it also talks about the ways in which Black women are experiencing racialized violence and sexualized violence at the hands of white men in the South and having little recourse, while white women often — and we can talk about this common trope, that Black men are dying after being accused, being killed after being accused, either legally or extra legally, after being accused of raping white women. So it becomes a case that can talk about that. It also becomes a case that Black women can step into leadership in because of the circumstances and the centering of Ingram. And they make a point, they don’t want to center Ingram’s sons, they make a strategic point to center her as a mother, because there’s always contested questions of whether it’s sexual assault where she was fighting. It’s interesting that the man that kills her is a sharecropper with her. They’re both sharecropping land. I think the ways in which we think about sharecropping is something only Black folks experienced, but the ways in which economic exploitation crosses the color line in the South in important way. But they’ve been having these contestations across this land as they’re both sharecropping for a while, and this is the end result. The question of whether it’s sexual assault is something that people are like, “We don’t know. . .” and the Black women decide, Black women will believe this, women will mobilize the case around this, and we will push this, we won’t keep it to the back, we won’t not talk about it, we will make it front and center. And we will articulate that as part of the reason that she should have the right to defend herself, which is, if you think about the 50s, a really bold claim to make. If you contrast this with the Recy Taylor case — which is another major case around a Black woman who was assaulted and then raped, and there was an effort to mobilize for justice — it was in some ways — and that was so difficult, that was a case where they really struggled too, and she was seen as the victim — they were committed to mobilizing around a case where Rosa Lee Ingram, a poor Black woman, not married, wasn’t seen as the ideal victim, was seen as the aggressor in this case, and they were going to articulate a defense for her on the grounds that she was defending herself, and her sons were defending her, and Black women have a right to defend their bodily integrity. I think that was important, and I don’t want to underestimate the importance of taking that stance. If we think about a moment where the questions of sexual assault, even today, are not, we have struggles to mobilize around it, always calls into question, not just a perpetrator, but the people, the person who suffer, that you have to have some ideal presentation to be seen as an ideal victim of this. But they are committed to this case for those reasons, in part because they say it speaks to the experience of so many Black women who don’t get heard, whose experiences of this don’t give voice, and they do a whole range of organizing.

One of the things I found really interesting [was that] I myself started out as a historian of the progressive era — so late 1890s and early 1900s — and I love reading about Ida B. Wells and Mary Church Terrell. Mary Church Terrell is one of the key activists in this case. She was an activist in the 1890s. And in the 1950s, she takes up this role in the Ingram case, because she thinks it is so central to what she’s been working on for a lifetime around Black women’s rights and defending them against sexual violence. She’s one of the key voices and the Party is very excited to have such an esteemed person take up their case. She’s organizing around it, and particularly Beulah Richardson does a lot of organizing around it. She writes a powerful poem in support of Rosa Lee Ingram and travels performing it.

In fact, it is a case that they don’t have a lot of success. They do prevent her and her sons from being killed. They are sentenced to death by electrocution, [but] their campaign and mobilization halts that. But they are held in jail for quite a long time. They don’t actually get out until I think 1959. So, they’re in jail for quite a while after the case, both her and her sons, before they get freed. But they are committed to it up until the end, organizing, trying to mobilize campaigns around it, doing Mother’s Day protests around it, sending to the state, to the governor, Ingram support cards. I think it’s one of the early . . . We think now about, say post-Black Panthers, about all these defense cases that have mobilized around Angela Davis, perhaps most famous Assata Shakur, Mumia [Abu-Jamal], but this is one of the early ones where they’re trying to create this campaign to defend this Black woman and her family from the criminal system in Georgia that is really just discounting their lives in some ways. I mean, they get convicted like an hour into trial one day. So, I think it becomes an important mobilizing point for these women and also for taking a stand.

I will say, I think one of the strengths of the Communist Party is that it’s willing to take up these cases to defend these people who are accused of crimes. In this moment in the 50s it is a bold step to take, and they’ve been doing it since the 1930s. Many people call them out, think they’re using the families and this but they contribute a lot of energy and time. Many Black women are at the core of organizing and thinking strategically about how to build up a lot of these defense campaigns that happened in the 40s and 50s, and mobilized broad support, and Rosa Lee Ingram also mobilizes broad support across the country, and it becomes one of their cases. I did some interviews of folks who joined, where that was the thing that brought them into this circle of the CP, and even though they were redbaited for it, they were like, “It doesn’t matter. This case is more important than the pushback I might get from being involved in an organization that’s affiliated with the Communist Party.” So, I thought that was a powerful thing too, how people make these choices around certain things that they think is worth the risk.

Hagopian: Yeah, it is striking how incredible some of the work the CP did. We can talk about the important critiques that the Black women brought into the Party and needed to change the culture, but also just these incredible anti-racist campaigns, when so many people were afraid to do any left-wing organizing because of McCarthyism — Communists, and specifically the Black women, taking the lead is just really inspiring to see.

Gore: If I could just say one more. I think the other thing they do that’s building towards the [We Charge] Genocide petitions, they do a petition to the UN, the United Nations, in support of Rosa Lee Ingram and the injustice she’s facing. I talked about this in the book, the protests they are going to do with this, which I think is funny just to see; I love finding moments where people are thinking about how do we organize a protest. But they plan this protest, this skit they’re going to do at the United Nations and part of it because they see it not just as an issue about the U.S., but an issue that has international implications.

Hagopian: Yeah, thank you. Well, there’s great stuff in the chat. It looks like some people had amazing breakout groups and really dug into this history. One question came in that we can take from the audience. It says, “For classroom teachers looking to include this important history in their teaching, but wondering where to start or where to focus, is there a primary source or a story that you believe would be a great place for them to start?” What’s the entry point to this work in a K–12 classroom?

Gore: I think there are many. There’s a great film that LisaGay Hamilton’s done on Beah Richards, it’s called Beah [: A Black Woman Speaks] , and it’s a story about her life. But it talks about her early activism because she becomes a pretty well-known actress. She’s in The Practice, she’s the mother in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. But before that, when she’s young, she’s involved in all of this organizing, involved in investigating some of these cases of what they call illegal lynchings, people caught up in the criminal system, defendants. And that’s a great place to start of someone’s life. I also think it’s great to start with any of the women. You can find information about Vicki Garvin now online, Thelma Dale Perkins, and their life stories, because many of them don’t have these extraordinary lives. They are making decisions about how to create a world they want to be in, and that leads them down this path to this collective work. Thelma Dale’s family has a great archive, some of it’s digitized, at the Anacostia Library here, which I like to use. Then the other thing I’ll say is the Beulah Richardson poems — I think if you Google “A Black Woman Speaks” you can actually find her poetry. I do find history is a really great place to start because you both see their creative expression of it, but also, if you spend some time, you see the theoretical intervention she’s making in that. So I find that very useful. Then I’ll give one more plug to one of my favorites, Vicki Garvin. You can get oral histories of her at the Freedom Archives that have a lot of it digitized, and things like that. So, I think that’s a great source to think about these individuals.

Hagopian: Yes, yes, that’s such a wonderful place, I think, to leave us, just giving teachers that specific way to get this rich history into their curriculum is so important. Someone wanted the name of the film again, before we wrap up.

Gore: I think someone put it in the chat, Beah: A Black Woman Speaks.

Hagopian: Excellent. What a rich conversation. You gave us so much to think about. I really appreciate it. I think that teachers, anytime you’re teaching about the intersections of class inequality and racism and sexism, where did that kind of theoretical framework come from? This is where to start. If you’re teaching about McCarthyism, you can’t teach about it without understanding Black women’s role during that time period. There’s just so many different entry points, and I hope that everyone here will share stories of their teaching. If you find important ways to bring this into your teaching, let us know so we can share it with others. And in a moment we’re going to do the evaluation form, but before that, please unmute yourself and share your thank yous to each other for your commitment to learning and teaching people’s history.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Audiogram

In this ninety-second audiogram, Dr. Gore describes the legacies of struggle that Black women spearheaded during the Red Scare and beyond.

Resources

Many of the lessons, books, and articles recommended by the presenters and participants.

Lessons

|

Framing Black Power Through the Life of Rosa Parks by Tiffany Mitchell Patterson and Jessica Rucker Subversives: Stories from the Red Scare by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca Teaching With Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca |

Books

|

In addition to Dayo Gore’s Radicalism at the Crossroads: African American Women Activists in the Cold War (New York University Press) and Want to Start a Revolution?: Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle (New York University Press), the following books were referenced. Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision by Barbara Ransby (University of North Carolina Press) Organize, Fight, Win: Black Communist Women’s Political Writing edited by Jodi Dean and Charisse Burden-Stelly (Verso) The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks and young readers edition by Jeanne Theoharis (Beacon Press) Until I Am Free: Fannie Lou Hamer’s Enduring Message to America by Keisha N. Blain (Beacon Press) 101 Changemakers: Rebels and Radicals Who Changed US History (Haymarket Books) |

Articles, Art, and Archives

|

|

Listen to Dayo Gore on the Wilson Center’s International History Declassified podcast, where she discusses Black women activists of the Cold War. And check out Gore’s “Eslanda Robeson’s Journey,” a review of Barbara Ransby’s Eslanda: The Large and Unconventional Life of Mrs. Paul Robeson (Haymarket Books). Disguising Imperialism: How Textbooks Get the Cold War Wrong and Dupe Students by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series) More than McCarthyism: The Attack on Activism Students Don’t Learn About from Their Textbooks by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series) “The Poem That Inspired Radical Black Women to Organize” by Ashawnta Jackson (JSTORY Daily) Vicki Garvin collection at Freedom Archives The West Oakland Mural Project |

This Day In History

|

Sept. 29, 1951: “A Call to Negro Women” Sojourners for Truth and Justice Dec. 17, 1951: “We Charge Genocide” Petition Submitted to United Nations Dec. 25, 1951: Murder of Harriette and Harry Moore in Florida March 30, 1952: Charlotta Bass Accepts U.S. VP Nomination June 12, 1956: Paul Robeson Testifies Before HUAC |

Participant Reflections

With more than 200 attendees, polls showed almost 55% were teachers or teacher educators, while another 10% of attendees were librarians and historians. Here are more comments that participants shared in their end-of-session evaluation.

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

Oh my goodness, too many to count; I have a page full of notes. I love the paucity of frameworks and the ways Black women formed spaces of liberation and solidarity.

Black women were integral in organizing and leading grassroots organizations in the McCarthy Era. Their individual stories are impactful.

One very important idea that I will use in my classes, is to share the stories with my students using poetry and news articles written by these ladies. My students really resonate with poetry and can really see connections between the poetry and the history.

Reminder of the importance of community; activism built from collective efforts. Even when organizations disappear, the connections often sustain and inspire the next iteration.

The importance of teaching female activism and agency.

The importance of intersectionality in teaching the truth.

There were so many stories that Dr. Gore shared as well as Jesse. . . it’s hard to pick one.

There were many stories of individual women that I was not aware of. I am an immigrant to this nation; not sure if this is also a reason much of this is so new. I was struck by the connection to the Communist Party. This will be anathema to teach in Florida, however! But the parallels to McCarthyism have been helpful and inspiring.

The people doing the work aren’t often in the spotlight, but we need community to survive and to do the work.

It was all important. The most important thing was that there is a beautiful community of like-minded individuals.

What will you do with what you learned?

I will incorporate this information into the unit I am currently teaching on the novel 1984 during the Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action as we connect the themes of the book to the activist struggles from Orwell’s time and today.

I really appreciated the entry points discussed and suggestions towards the final discussion. There is so much information and rich resources that suggestions for entry points and for conversation starters are really appreciated!

As a librarian I will bring more books about Black girls and women.

Grateful to have more resources to help me show students that organizing is messy and that it takes all of us!

I will teach about the intersectional racial justice work being done within the Communist Party — not separating the Civil Rights Movement and the McCarthy era.

I’ll definitely include these women as part of a project on Black radicals that my students are already doing.

I will use this in my U.S. Government class as an example of historical figures making change, to use as an example for my student’s action project about how they can make change.

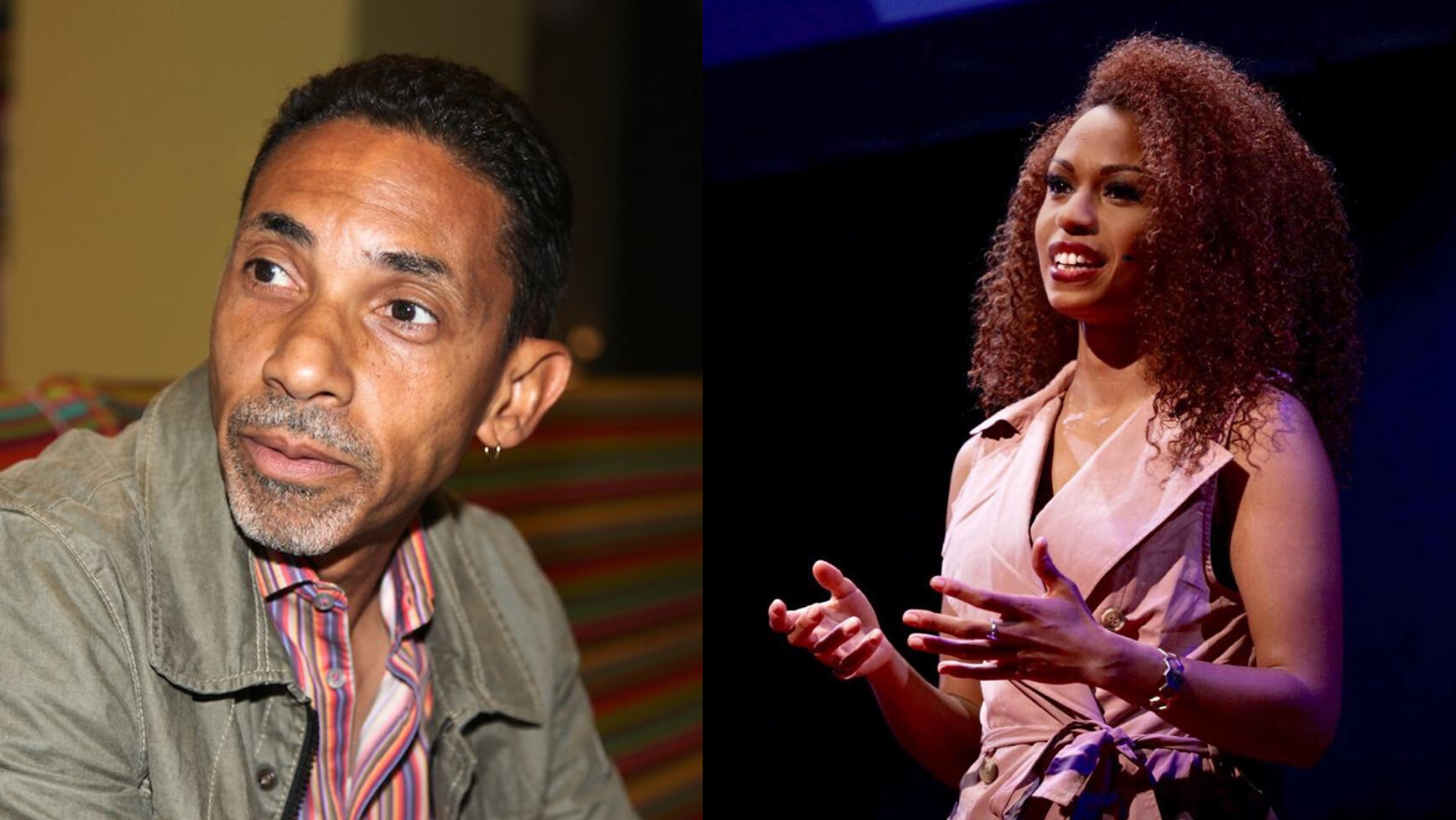

Presenters

Dayo F. Gore is associate professor in the Department of African American Studies at Georgetown University, author of Radicalism at the Crossroads: African American Women Activists in the Cold War, and co-editor of Want to Start a Revolution?: Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle. Gore is a member of Scholars for Social Justice and currently working on a book length study of African American women’s transnational travels and activism in the 20th century.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing, and on the staff of the Zinn Education Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn