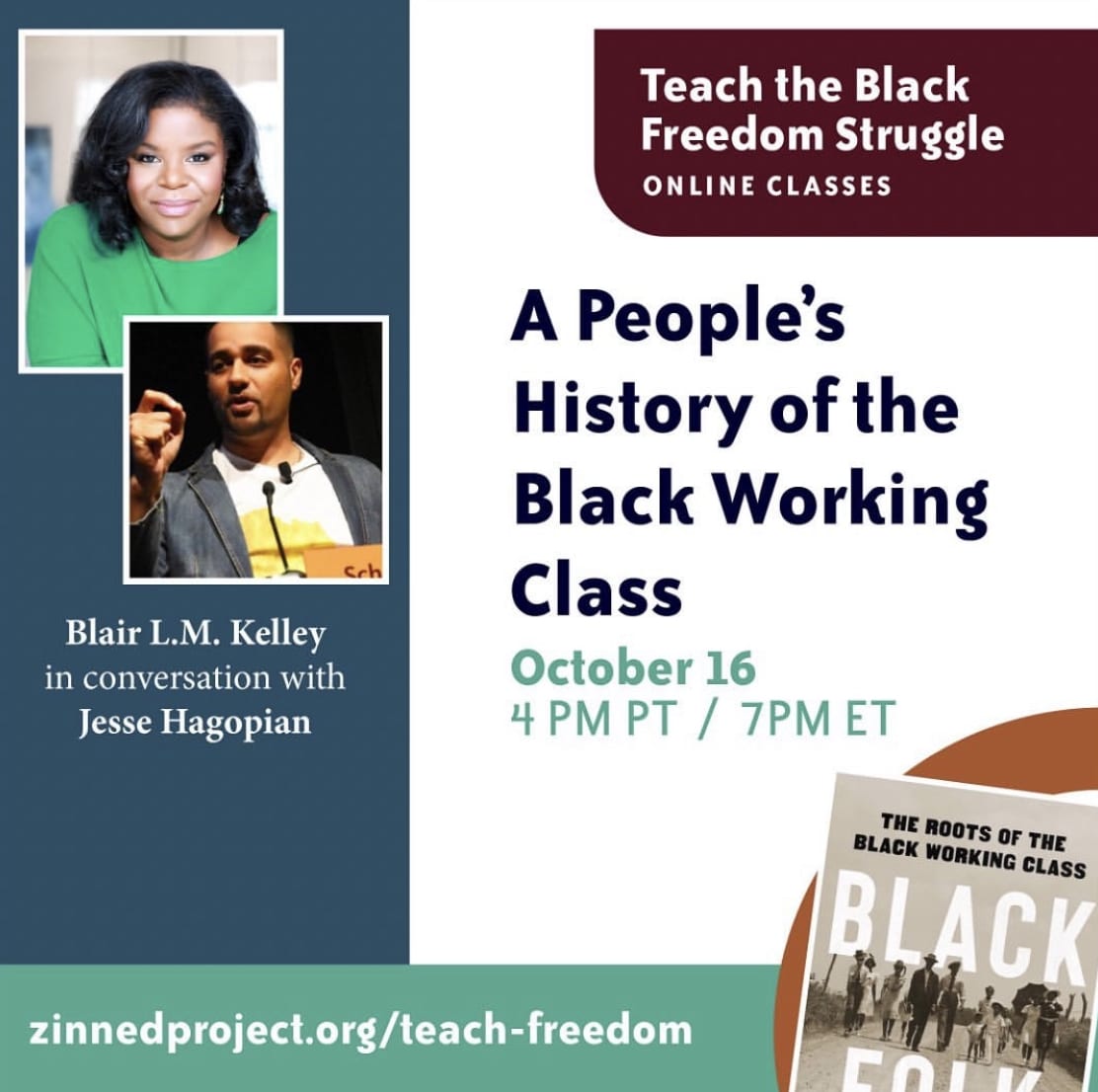

On October 16, historian Blair L. M. Kelley joined Jesse Hagopian to discuss her new book, Black Folk: The Roots of the Black Working Class.

On October 16, historian Blair L. M. Kelley joined Jesse Hagopian to discuss her new book, Black Folk: The Roots of the Black Working Class.

This session was the latest in our monthly Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online class series. Don’t miss upcoming sessions — register now.

Participants shared what they learned and the impact of the session:

I loved Dr. Kelley’s stories of her family, and how she connected her family stories to the stories of the Black working class in general.

“When we don’t talk about Black history, we’re missing part of the story about this moment.” This was a huge key theme — that the work done by the Black community to unionize and fight for labor rights is critical to the prosperity of all workers.

I loved the discussion of women as the labor organizers through washing and care-taking; Black women were always powerful organizers!

I learned how there are pockets of hidden history that are impacting us now. However, due to the lack of not knowing these pockets of history, communities are lost and do not understand why things are the way they are. Which is not by accident.

The Florida standard stating that slavery was “beneficial” to enslaved people makes me think about the erasure/dilution of Reconstruction from most U.S. history curriculums.

Dr. Kelley really reminded me that not everyone has the same ability to trace back their own cultural history. Culture is a fundamental part of a society, of a people, and to be denied it must surely be deeply painful.

I enjoyed learning about agricultural workers as part of the labor force, even if they are not always thought of the same as factory workers.

There were many important stories and ideas tonight, but the one I am thinking about is the Pullman porters. They were well-spoken and educated, they were hired to give a feeling of plantation elegance, but they were bound to get into “good trouble.” They were smart, they were educated, and they were going to use their skills to advance their people.

Event Recording

Recording of the full session, except for the breakout rooms.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Thank you all for joining us this evening. I’m so very excited to welcome historian Blair L. M. Kelley, the author of two of our favorite books, Right to Ride: Streetcar Boycotts and African American Citizenship and also Black Folk: The Roots of the Black Working Class, an incredible book. Dr. Kelley, thank you so much for being here with us this evening.

Blair L. M. Kelley: Thank you so much for having me. I’m thrilled. This has been on my calendar for 1,000 months.

Hagopian: Right on. I’m just thrilled that we have hundreds of teachers here this evening who will be better able to pass this knowledge on to their students. I wanted to dive into a discussion that you really start from the very beginning of this book. I deeply appreciate you framing the book with the question of who is the working class, because you point out that often the words working class are synonymous with only the white working class. So I wanted you to break down what’s wrong with that narrative, and why did you feel like it was so important to reclaim the history specifically of the Black working class?

Kelley: I think it’s interesting because it honestly was a question brought to me by my editor. He had read some books recently on the white working class — a lot of storied and important and impactful books that have sort of set a political moment were about the white working class — and he wondered what is the Black working class? Shouldn’t someone be asking this question? So he went around to some of my favorite historians, and then finally to me, and found someone who was interested in engaging in this question with him. So, for me, at first I thought, “Well, I’m not the person who can even do this, because it’s a huge subject. It’s a fraught subject, and I’m not a labor historian by training. I’m a historian of the African American experience. My first book was about transportation and segregation, and I’m like, “Can I even do this?”

But I have been writing about Black working people my whole career. I’ve been writing about everyday working class Black folks and the impact that they had on their world. As I began to think about it, I was like, “Well, maybe?” He said, “Well, how would you do it?” And so I thought about my family, and I thought about my grandparents, I thought about my father’s work, I thought about my ancestors and the journey that they had taken through the migration, growing up as southerners, becoming migrants, finding work, not finding work, the challenges they faced, and I thought to myself, “Well, I don’t know that I’ve ever seen a book that would center people like my folks.” Not people who appear in some archive because they’ve written a document, or they started an organization, or they were at the head of a civil rights group, but just everyday working people and their journey. I’ve always been fascinated with retracing and remaking and seeing what we can remake of the everyday, and so that’s where I began.

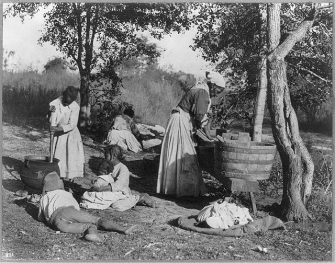

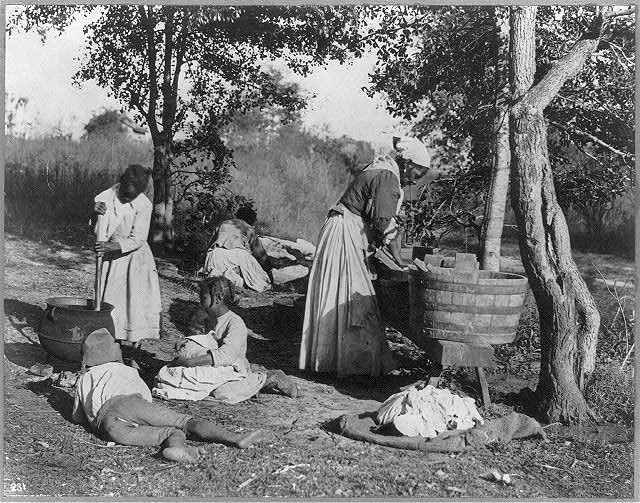

Then I began to think about, “Okay, what are the fields that are kind of gone now in many ways?” Some of them are still with us, but I thought about washerwomen. I loved Tera Hunter’s To ‘Joy My Freedom. I consider it my bible, the book that made me know I could do history in grad school, and know that I could write the kinds of histories I wanted because she was finding folks that would be really hard to find. I was just in her footnotes and piecing things together and figuring those things out. And so the washerwomen have been central to what I thought about when I think about this history. They were in my first book, and I teach about them constantly. I teach that book constantly, and so I was like, “Oh, I’ll see if I can write about washerwomen.” Then I thought about the Pullman porters, who have, again, been central to my teaching, central to my writing, because of the train, and I was like, “I could definitely write about them. They’ve been written about, but I think I might have something more to add if I go back over this again.”

Then I had been working on a book when I got this invitation to write a book, and it happened to be about Black women domestic workers in Philadelphia. So I had whole chapters and research and amazing things that I had discovered in that journey that I didn’t know just from the secondary meetings I had done. So I was like, “Well, I already have this body of research, so let me see if I can just pull from this and pull from this, because I think I have some pretty cool things to say” — and they were pretty amazing, they were probably going to get unnoticed in the book I was writing, but they might be noticed if I talked about them here. Then I thought to myself, “Why aren’t agricultural workers considered the working class?” Because we focus on the factory floor, generally, when we think of labor We don’t focus on agriculture. That’s a Marxian understanding. So you can’t really organize anybody in a field. I always thought that was problematic when we think about Black working people. Why not think about the ways in which Black people were organizing in those fields? Then I started to think, “Well, why are we not talking about enslavement?” I know that they are not workers, yet, in a classic Marxian sense, but if you want to know where Black people come from, if you want to understand our roots as a community, as a people, they start in those fields. So I will write about that, too. It’s my book, so I started getting bolder and bolder as I went.

Then I wanted to talk about postal workers, because I think other than Philip Rubio’s amazing work, which is very under-studied, very misunderstood, and not thought of as a site of resistance, and a real fight that Black people needed to get to those jobs. So, all of a sudden I had a story and a framework that I was excited about writing, and a way that I could approach it. Now, mind you, I got freaked out along the way, like when I sat down to write about washerwomen, I was like, “Wait a minute. Your very favorite book is all about washerwoman. Now you’re going to have something new to add.” But I found new things. You know, AI is an interesting technology. But, boy, it can search through some old newspapers in a really interesting way. So the things that I could discover quickly with searches, and then I had hundreds of results about things I had never seen before and never heard of before from new places, because those newspaper technology search engines are reading those papers, and you know they can see Negro washerwomen in a way that would have taken us hundreds of hours of spinning just to find one. So there was all of a sudden, on top of the beautiful research that Tara Hunter had done, a whole other world that I discovered that there were tiny Atlantis’ all over the South. It’s just been a journey to put together what is the working class. And when I did that, I discovered this is not what America is thinking about as a working class. They’re thinking of white men in the Midwest during election season. “Let’s go ask them what they think about the presidential race.” And that’s sort of the main way the media approaches the question of working class. Black people are discounted in those spaces, they’re not thought of as workers or thought of as the poor. They’re thought of as problematic. They’re thought of as lazy, going, again, back to the tropes of slavery. They’re not centered as workers. But if we center them, I think you get a whole new history of the American working class.

Hagopian: We certainly do. It’s a fascinating history that you’ve written here, and I am excited to go through those different categories that you mentioned. Before we dive into some of those stories, just to follow up, I wanted to ask you why this is important for educators, specifically our audience here today. Why do they need to know this history?

Kelley: I think there’s a way in which American history creates this notion of a classlessness that I think is problematic. If you go into your classroom and say, “Hey, what class are you?” — which I don’t suggest you do — everybody’s going to say they’re middle class, “my family’s middle class.” Now, you could teach in a wealthy community, you could teach in an impoverished community, and they’re all going to say they’re middle class. I went to college with people whose parents in the 1990s were making 3 or $400,000 a year, and they were like, “We’re middle class.” I’m like, “No, no, no, not really.”

But, there’s a way in which, in American society, we don’t talk about the working class. We don’t talk about unions and organizing. Over my lifetime, unions and organizing have been demonized as somehow problematic and deteriorating the fabric of American society. And I live in North Carolina, I mean, you’d have a very hard time organizing a union in this state because people have been raised to believe that unions are problematic for workers. We’ve lost this broader sense that sometimes workers need to get together with one another. There are things that they deserve, there are things that they need to have a decent living, there are things that they deserve as humans, as Americans, as people who are putting in their labor.

If nothing showed us this, then the COVID moment for me was an incredible one, particularly for teachers, for us to know that if we don’t discuss what workers deserve you end up in this situation where people are like, “Well, you should be thankful.” No. Workers deserve time off, protection with their health, child care. I mean, it’s all kinds of things that if we really sat with the question of the working class for our young people they can begin to ask new questions. And so I was thrilled that in the COVID moment we are beginning to ask those questions. We see that in all the organizing that’s happening now, that’s enlivening every sector of our society and broadening that conversation. And so I’m happy to have a book that really can provide another perspective as to why we need to think about workers, especially with our young folks, so that we can change what we’re doing. There’s enough that we can provide for everyone in a humane and decent way.

Hagopian: Yes, I’m with you. I love how you take an expansive view of what the working class is. I also really appreciated that you started the discussion about the Black working class in the experience of slavery, and your own ancestors, too. My family has been doing a lot of research recently on our own family history, and recently discovered which plantation our family had been enslaved on in Mississippi, and it just made it so much more real for me to understand the direct lineages between that experience and then how our families developed in our work history. So, I thought it was an important decision to ground the book in the experience of enslavement, including your own family’s history.

As you know, Florida just produced official state education standards that declare that slavery was of “personal benefit to Black people,” saying that because some of them got training in blacksmithing, as if slavery was like a job training program. I mean, it’s so absurd that you have to almost laugh to keep from crying. But when I heard that news about the Florida standards I thought about you writing about your ancestor, Henry, who was a blacksmith but was also captive in a way that no other group of working people were. So, can you tell us more about him and about why you root the book about the Black working class in the history of slavery?

Kelley: So, just two important things to clarify my response to Florida’s standard about slavery as a jobs program is that it’s important for us to know that the people who were forcibly brought to these shores came with skills. They came with knowledge. They were brought because they were valuable, because they had [knowledge]. They were iron workers, they were stone workers, they were people who knew how to cultivate rice. They had to teach the planters in South Carolina how to plant the rice, how to flood the fields, how to build the levees, how to drain the fields, how to pound the rice. Those are African technologies. So not only the things that we think of as “skilled,” which I kind of debunk in this whole thing. I think all of this is skilled, not only the metalworking, the brick making, all those things that enslaved Africans brought with them. But every enslaved person brought knowledge that was used and built the wealth of this country. So there’s that part. It wasn’t a jobs program where they were taught by others how to do the work. They knew how to do the work, and they were oftentimes teaching others. They were valuable because of that.

The second piece is at the end of enslavement, as Du Bois said, the end of slavery was a deskilling of the Black working class, so Black men pretty systematically in the field that we have traditionally called skilled were prevented oftentimes by a statute from having jobs as brick masons, as stone carvers, as iron workers. They could not have the more highly paid skilled jobs available to them as enslaved laborers as freemen did. So if it was a jobs program then they didn’t even have the chance to get the jobs after slavery ended. So no and no.

I was enlivened to discover my ancestor Henry on a part of my family tree that I’ve had such a hard time with over the years. It took me basically about 12 years to get that part of my family tree to work on that side. I have a piece of my family that goes back before the American Revolution on my dad’s side, in part because they were free in Maryland around 1800, so I could see them really far. My mother’s part of the family, the Blair part of the family, goes back really decently for me, probably to the early 1800s, in part because their last name was Blair and that’s a weird last name for Black people. But on my grandfather’s part I just couldn’t do it for a while. Then, as I worked on this book after my mother’s passing, things started working, and I started seeing new things. I found a granite gravestone for my two times great grandmother, and I was like, “Wow! That’s an elaborate looking stone. She must be from a place where they had a lot of stone.” So I started in and I discovered Albert County and then the tree really began to work from there. Then I found Henry, who was born probably around 1822 or 1824. His mother was probably born in Virginia. I can’t know anything about her, can’t find anything.

But I was able to trace Henry’s life, who was probably the man who owned him in bondage. I was able to see him in enslavement and then find him in freedom. I was able to really piece together a history of Albert County in ways that were phenomenal to me, and just such amazing coincidences for it. There was a book called From Slavery to the Bishopric written by Bishop Heard in the AME Church. I collected that book in graduate school for a collection at Duke University called Black Voices because I was trying to make sure we had all the Black autobiographies from enslaved people, not just sitting on the shelf circulating when they were irreplaceable. So I was like, “Let’s get these books down.” I remember that book, I was like, “Wow, that’s a hard hitting title.” Then I use that same book for Right to Ride because he sues the train after he’s assaulted, when he’s traveling. Then I was doing research on Albert County, and I was like, “Bishop Heard is from Albert County, and he grew up five minutes from where my ancestors were enslaved.” So that book has been insistently in my life for decades. I was so thankful to have his story, to have his accounts of his growing up around the same time as my ancestors in the same community, and just to be able to piece together a history of community and the ethic of Black working people that comes from this moment of enslavement, the way that Black people are able to survive, the way that they are able to build together, comes from this community of survival, of resistance, of private joy, of worship, of crafting their own world view. So when we wonder how well Black people were able to do as free people, it is because they were surviving and coming together and they’ve been remaking who they were in enslavement. If we want to know who the working class are, we’ve got to know where they came from, and they come from this moment. So it was such a joy to do it in a personal way, to see that collective way in which millions of people were working to remake a family life and community and build their understanding of their place as workers and laborers.

Hagopian: Oh, that’s beautiful! I just love how you weave your family history in, to draw people in and share about who you are, and then use that to widen the lens to look at the Black experience in general. It’s just such a brilliant method and it makes the book a page-turner. I loved your discussion of the Black washerwoman in the book because all too often the period of Reconstruction is skipped over or only briefly covered in most K–12 classrooms.

You write about some of the important struggles for Black working class women during the era. You wrote, “After slavery ended, white Southerners attempted to construct a racial order very similar to what had existed before” and you wrote that “all Black women’s laundry work was borne both in compliance and defiance of white authority.” I love that phrasing and that understanding. So, I was hoping you could talk about the mass industry that laundry work became, and the central role that Black women played in both their exploitation and their resistance.

Kelley: Absolutely. It was fascinating to me to see the degree to which laundry work was stigmatized as Black women who were enslaved did this work for the majority of the time. Many poor white women would sacrifice anything and everything not to be seen doing laundry. It’s very public work, so if you wash your own clothes, you’re in your own yard with washpots, you’re hauling stuff, you’re making soap, you’re hanging your clothes in your yard, and so everyone can see that you are doing that work. So in this sort of genteel sense of the white womanhood and her household, if she’s at all trying to keep up an image that she has this proper household, she’s going to have Black women washing her laundry. It’s not expensive and that’s what she wants. So the degree to which you see white people go to great lengths not to do laundry stuck out to me.

There was a man who was a former slaveholder, whose enslaved people all left the plantation when the army came through. He had daughters, and he was an older man, and he said, “Well, I’m going to go do the laundry because my daughters cannot sustain the blow of having people see them do laundry.” So I was like, “Okay. Because we all do our laundry now, for the most part, and nobody thinks of it as stigmatizing work, and we have such a different emotion about it.” So I was like, “Well, this is important here.” I think Black women were aware that white people did not want to do their laundry. They were like, “Okay, cool. So we’re free and now you want us to do your laundry.” White families wanted Black women to come to their yards and do their laundry, so they could watch them and time them and supervise them. Black women were like, “No, thank you. We’re going to do the laundry. We’ll pick it up and we’ll bring it back to our homes. We’ll start on Monday morning, we’ll get it over the weekend, we’ll wash on Mondays and dry and press on this day and that day.” So they had a schedule. It was pretty systematic across the South. When I looked at different communities and different conversations, it was very systematic. Then they would deliver the laundry back to the family on Friday and pick up the next load. That was it. What that gave them was that they became the first stay at home moms who were working. The first Zoom workers right?! They zoom their laundry home so that they could watch their own children — which was a pleasure and a gift, something they could not do when enslaved.

This is what they wanted. So they sought out the means by which they could maintain their own households and still support their own households. Now, did they make a lot of money? No. But they had autonomy. They had a degree of safety against rape and attack from whites that existed in white households. And they made this decision. One of the most powerful things I rediscovered — because it’s in Tara Hunter’s book — is that the washerwoman of Jackson, Mississippi, in 1866, got together and formed a union and they made these demands about where they’ll do it and how much they’re to be paid. They’re demanding a living wage in 1866.

What’s powerful to me is that I was taught in graduate school that workers need organizers to come in and to tell them how to organize, how to think about their labor, to raise their consciousness. So in 1866, a group of women who had been in bondage a year before, organized a union demanding a living wage and to set the terms of their labor, all on their own. For me, the resounding reminder of something I’ve always known is that people don’t need their consciousness raised. Workers know what work is. They need space, they need support, they need time. Sometimes they need someone from the outside to buffer them because they might get fired, but they certainly don’t need to be taught about work. Workers know about work, and Black workers know about work.

Hagopian: Yeah, no doubt, that’s really a great lesson for us to carry forward. You can see why a lot of people are scared of those kinds of lessons being taught today. We just have a couple of minutes here before we move to the breakout rooms, and we can come back and continue the discussion with more questions after the breakout. But I will get you one last question here.

I love the section on the Pullman porters. It’s such an inspiring struggle, and it gave me such a better insight into the nature of that work. You write about how the waves of Black immigrants from the South to the North that made up the Great Migration really transformed the character of the Black working class. While their labor was hyper-exploited, it also gave Black people an important position of working in key industries like manufacturing and railroads. This is really the basis of where the Pullman porter union takes off and serves as a guide for all Black workers, and for the working class in general. So, I’m hoping you could talk more about the Great Migration, the impact on the Black working class, and specifically the Pullman porter struggles?

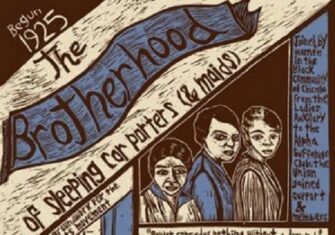

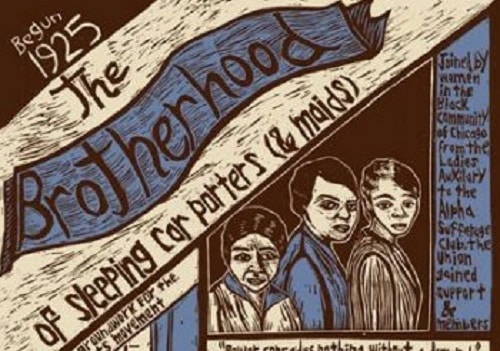

Kelley: The Pullman porters ended up being an all Black labor force, in part because the founder of the Pullman Company — the man that innovated a sleeping car so you can sleep comfortably on the long haul train — he wants all Black men working on these trains. He wants to evoke plantation slavery. He wants you to have a man-servant waiting on you hand and foot, and giving you everything you need. And he accidentally creates the largest private employer of Black men in the United States. And he locates them in these cities in the North — they’re in Philadelphia, New York, Chicago. They end up being based there. They’re often Southern born, but they’ve migrated North. They’re often quite educated, because he wanted someone who could speak well. They oftentimes had a high school education, and sometimes even college education. So he ended up with a population he thought he could exploit but who ended up really using their positions to be facilitators of the migration for others, and also organizing the largest all Black union in American history to that date, not only advocating for themselves as a class of workers, but to change what’s possible for Black workers throughout the country. They’re successfully lobbying the president to desegregate —FDR — during the defense employment, they were successful in doing that. They were organizing what became the March on Washington Movement which led to the March on Washington that we know about in 1963. They were threatening it when they first were organizing, and so they were never just about Pullman workers, and also they were never organized and supported by just Pullman workers. It was a collective community, a broad, powerful movement of Black workers and Black people, and Pullman porters were representative of that movement and the ways in which Black unionizing is this broad, rich, deep thing that is unique in American history.

Hagopian: Yes. It was really cool to see in the chat that Don says he’s a proud, great, great, great, great, great, great grandson of a Pullman porter who migrated from Alabama to Chicago. That’s beautiful. It’s amazing, like I said, to see my family history, but it’s everybody’s family history. That must be such a fun part of sharing this book with the world is the connections you’ve made with people like Don here. I remember seeing the movie 10,000 Black Men Named George about the Pullman porter struggle. I haven’t seen it in a long time, so I can’t remember if that’s a great resource, but it seems like something else that might be able to help support this work.

Kelley: I remember enjoying it. I remember enjoying it when it came out.

Hagopian: Well, somebody here should watch it again and do a review for us so we can recommend it as a resource for educators.

[breakout rooms]

We’re going to jump back into the conversation. I have a few more questions that I would love to ask, and if people have questions that they also have, please drop them in the chat and we’ll try to get to those if we can. We would love to. Did you have fun in one of the study groups, Dr. Kelley?

Kelley: I did. I had some African American AP students once who didn’t point out that they learned about the Pullman strikes of the white workers but they had never heard about the Black side of Pullman, and I was talking about how it would be powerful to combine those two stories together rather than sort of segregating them the way that George Mortimer Pullman did. Because it teaches you a lot more about the challenges that came to white workers in organizing, and that only workers who were allowed to live in the town Pullman, and to benefit from some of the largesse that he was trying to give workers, that they, of course, found uncomfortable and limiting, and the degree to which he was trying to keep Blacks workers separate. He believed in segregation, he was a segregationist. But having this all Black space enabled them to really powerfully counteract the forces organized against them. So it’s a great story together, and a piece of American history.

Hagopian: I’m glad you got to check in with some of those students and educators. That’s beautiful.

Kelley: Someone asked me in our closing seconds if I had a moment of surprise in the book, and I laughed in terms of my research, and I laugh because there are a million. So hopefully, I mean literal just joyful surprise and then heartbreaking surprise, and all kinds of things that I did not know about my family, about history, about the perspective that you really take when you take on this question. So maybe that could be our last one of our first questions from the audience.

Hagopian: Yes. One of the ways you expand our understanding of the Black working class is by focusing on Black women, because we know that oftentimes the working class is discussed primarily as male, primarily as white. And not only with the washerwomen, but also with Black domestic workers of all kinds, you have such rich writing about their lives. So I was hoping you could talk about the experiences of Black domestic workers such as Mini Savage and your own grandmother that you write beautifully about, Brunel Duncan, many of whom moved to the North during and after World War I. As you point out in the book, “they are not often the center of histories of the Black working class during the Great Migration.” So, I thought we should center them tonight.

Kelley: I think, again, we think of labor history as taking place on the factory floor. And because Black women were often atomized in households, sometimes they may be with another one or two people, but they don’t have that big collective in the worksite. So we thought of that as something that we couldn’t study in quite that way. But what was really powerful and a surprise for me was learning the degree to which the numbers of Black women who are working in household labor surges dramatically through the 1910s, 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s. It actually goes up. I mentioned change over time in the group because we think of Black women being maids in households as sort of unchanging. You know, “the help,” and this nonsense that we purport to learn from that film and other films where it is sort of this permanent fixture that Black women are in households.

But what was really powerful for me to understand is that, particularly during World War II, the surge of Black women into household labor for white families coincides with the push of white women into defense labor. You know, the Rosie the Riveter moment. We talk often about Rosie the Riveter and what it means, and yet we never say that, “Well, Rosie the Riveter could go to work because a Black woman, for less pay, came into her household and chopped her groceries, took care of her kids, started her dinner, and facilitated her ability to work in this time period when she was called to work.”

What was fascinating for me is that there were some Black women, of course, who were able to get defense employment, but it was much more limited. It was a fight. The NAACP advocates, over time, to give access to Black workers to defense employment. A. Philip Randolph is fighting over time for that, but it’s never in the same numbers. It’s never a parallel. The parallel really happens in the strata below, where Black women are then called on to facilitate this work — but without the national fanfare, without the thanks, without the benefits, without the higher pay. A thing that I guess I shadow knew, but I had never thought about it to that degree. Again, Black women working in households was the largest segment of Black women workers in the United States in that time period. Did they deserve organizing protections? They were exempt from federal protection; they were exempt from limitations in the number of hours and work; they were exempt from any supervision of worksite conditions; they were exempt from social security. Along with agricultural workers, which made up the bulk of Black workers, when you did that. That powerful work of exclusion for Black women in the time period on the federal level and then gets replicated in the ways in which we’re teaching labor history now. So, I wanted to correct that, and I wanted to not only speak to the personal burdens that these women took on but also the work that they were able to accomplish in spite of all those limitations.

Hagopian: That’s really great. Just the way you described what made Rosie the Riveter possible is such an important history that is not in the textbooks. Our students aren’t learning that. If you’re going to teach that era now, you have a new way to teach it much more truthfully. I’m so glad you shared that with us.

One of the most exciting parts of your book, I think, to me, was about the postal workers. In the book you write about the 200,000 postal workers staging the largest wildcat strike in U.S. history didn’t get official authorization from the union, but knew they couldn’t take it any more and were ready to strike. You write, “Starting in New York City, where 30% of postal workers were Black, the wildcat strike of 1970 tapped into the experiences that came from years of fighting white supremacy in the ranks of the postal service.” So I wanted to begin to think about Black postal work labor and the significance of the wildcat strike, but also how earlier struggles against white supremacy proved helpful in preparing Black workers to engage in labor militancy.

Kelley: Yeah, it’s powerful. We associate Black people with postal work. It’s a running trope and joke, “you just always work at the post office.” I mean, that’s the name of the book that is so excellent, because that’s just a thing we talk about. It’s extraordinary to know that Black workers were constitutionally prevented from doing postal work twice in our earliest history. It’s extraordinary that they wrote a law. First of all, postal work is the only working class labor delineated in the Constitution. That’s first. Second, they went back and forth, saying “this is for white men only” because it was considered to be so important, because it was considered to be so vital, and probably because it could have been a site of resistance. Because we know that the enslaved males used their ability to read and write and interpret to figure out what was going on, to revolt, to fight. The idea of Black men caring and moving, the private males, probably was also a threat. So we see the very first Black postal workers get hired after the Civil War. Many of them are veterans, some of them are very storied veterans, and I write about them in the book. But that fight for access starts in the 1860s, but goes on to the 1950s.

Here in Durham, North Carolina, where I am, they were fighting in the 1950s to get access to postal jobs. Even after they successfully took Civil Service exams, Black men who were postal workers, it was said [that they would] want to rape the white women. They delivered the mail too. Some of them were threatened, some of them were attacked on their postal routes. There was a Black postmaster from South Carolina who was lynched with his family because they were so threatened by him engaging with the mail. A poignant story that Ida B. Wells herself wrote about in Lake City, South Carolina. So, you know, it’s a contested sight. It’s a fight that Black people have had for the better part of a century just to get access. So they learn, they organize, they build their own unions, and it is that spirit of resistance that then can infuse postal work with the kind of radicalism and dignity of the civil rights fight.

Talk about Amzie Moore, one of my very favorite civil rights warriors in Mississippi. He’s a veteran, he’s a postal worker, and he is insistent on his rights, and he uses his federal employment, and the fight to keep his federal employment, as a means to which he can organize in Mississippi. That spirit of resistance, that spirit of the fight, that organizing and existence of a Black union, facilitates that larger mass fight in the 1970s in a really powerful way that I think would be missing otherwise. Amzie Moore had this brick house he built with his federal loan because he was a postal worker, a civil rights worker. He was the first person that Bob Moses met; Ella Baker sent him there. He is a key and a cog but he is like so many other postal workers. I mean, I think Heman Sweatt, who’s one of the postal workers who sued to break down segregation in schools. So it’s postal workers, it’s independence, it’s fight. It’s a powerful fight. I mean, what a great way to teach about movement history and union history.

Hagopian: Yeah, no doubt. In reading your book, I was really struck by the political dimension of Black working people’s struggles throughout history, as you were just mentioning. For example, you wrote of the great Black union organizer, A. Philip Randolph, you said, quote “from the beginning, Randolph framed the cause of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters as a fight, not just for better pay and decent hours, but for the betterment of Black America and America as a whole.” So I just wanted you to elaborate on why it is that Black folks aren’t just struggling for the bread and butter issues, but have expanded their working class struggles into this political dimension, as well. And I was just thinking also that one of those political dimensions often is environmental justice as well.

Kelley: Yeah, I think it’s really powerful to go back and see the degree to which this moment is grounded in this longer discussion about the broad sense of what’s possible. You can’t get to meaningful Black workers without this longer, broader history. That’s why I began in slavery; that’s why I’m talking about households and community; that’s why I’m talking about conversations that folks are having on their stoops; that’s why all these things are interconnected. Nobody was willing to just say, “Well, I just want to get more money at my job, and I don’t care about your job. I don’t care about how things are going for you.” That’s not the way in which Black workers are thinking, because they’re thinking holistically.

And again, I was trained in grad school that you study the workers at their job and just stay in this one part of their existence and keep them boxed into this one piece. No. I know Black community. I know the ways in which it’s happening in your church; it’s happening in your neighborhood; it’s happening on the streetcars and it’s happening on the bus. It’s happening on the postal route that the Black postal workers are walking through the neighborhoods. I know it’s happening in rural areas; I know it’s happening with sharing food; I know it’s happening with all these things. So when they are at work they are still their whole selves, and they bring their whole selves to it.

I always teach my students, just tap on the shoulder of the person that you want to trace and want to study. What did they see? What was their neighborhood like? Where did they go? Who are their friends, who are their enemies, [and] who do they hate from high school that they never talked to again? Get into it because it’s so much fun to really replicate them in ways that are like us. They were human, like us. They were imperfect, like us, and they lived in community. We can’t always rebuild it perfectly, but as we do, we learn so much.

Hagopian: I have just a couple last questions that I wanted to throw at you. Before I do, I was just so really struck by the chat this evening. I was just struck by how many people shouted out their groups this evening. It sounds like there were some really powerful discussions in a lot of the breakout rooms. It’s really fun to get to see educators all just in there figuring out how to change the curriculum and make it the way it should have been all along. That’s beautiful to see. Thanks, everybody who’s been facilitating those groups and participating in them.

One of the things that I especially appreciated about Black Folk was the way you pointed out that everyone has a stake in the struggles of the Black working class. You write that quote, “All along, Black working class folk have been the canary in the coal mine, suffering first from deindustrialization, a housing collapse, and an epidemic drug crisis. While race has been used by generation after generation of politicians seeking to divide and distract American workers from challenging the structural barriers that make it hard for the working class to get ahead, history and the present day are rich with promise.” I just loved that description. So, how have politicians used racism to divide the working class? And what do you think is needed to overcome these divisions?

Kelley: I think that that is the foundation of American history, that free white workers were taught that they were nothing like the enslaved, that there was some stigma, there was some line, that divided them. When, in reality, the existence of slavery devalued everyone’s labor. After freedom, white and Black workers were taught that they were somehow fundamentally different, and to cross the line and to organize with Black workers would be to stigmatize white workers. Somehow the wages of their whiteness were worth more than the degree to which they might gain from organizing with Black workers. So, we know this happened sometimes, we know this happened in spite of it, but it is the uncommon moment, it is the fleeting moment most often throughout the country. There is a lot to gain when you make people feel distinctly different than folks who are their working peers. There’s a lot of distraction, there’s a lot of manipulation that can happen in that space, and that is fundamental to the ways in which politicians have approached the working class in this country.

Hagopian: I completely agree from the very beginning. How do you hoard that much power and wealth? You have to convince the masses of working people that your enemy is the person you’re working with, or some other working class person.

Kelley: When you look at the degree to which there’s this mythology, and we still have it, that we’re all about to be really, really wealthy and we shouldn’t step on the opportunities of the wealthy because they’re right around the corner for us. In slavery, that was like, “Oh, you might own a slave one day.” Now, mind you, an enslaved young Black man was worth the equivalent of about $40,000 today. Your average working person wasn’t going to whip up and have $40,000, and even if they did, they would have one person in bondage, and their neighbor might have 300 or 400. So you weren’t about to be him. That wealth came before the founding of the nation, that wealth came through head rite and colonial policy that enabled the facilitation and the speeding up of land being taken from Indigenous folks and given to white folks, and using the bondage of the African to make it profitable. So, that game was over by the time they even started having that conversation. Yet people are like, “Oh, yeah, I should think of this as like me. We are white men and we are just about the same.” And they weren’t, and the same kinds of things . . . One of my very favorite books right now, it came out during the pandemic, is the Wages of Whiteness. The degree to which white working class people are willing to vote against their own interests and policies because they think of their race as more important, and that they would fear that a Black or Brown person might get some benefit, that they will not get it for themselves.

Hagopian: That psychological wage that is paid to white people is a tramp. It’s incredible how much, how all too often, they’ll take that wage instead of a real wage that could help their family survive. And why? But there’ve been incredible examples of multiracial struggle that give me hope, and we’re seeing a bunch of strikes today. I just thought I’d end our session by talking about the current moment we’re in.

We have over a quarter of a million people on strike today — whether it’s the UAW or the Kaiser health care workers, the Screen Actors Guild or the recent strike by the Writers Guild of America, and many others. From history, there’s an amazing legacy of Black struggle leading to more labor fight back, whether it was the Civil Rights and Black Power movement or today. So, what do you see as the connection there? What do you think the role of the Black working class will be in the labor struggles to come?

Kelley: I think they’re already playing a central role. When we look at Amazon workers and we look at Bessemer, Alabama — which is a place of historic struggle, historic Black labor struggle — it’s no accident that they’re one of the first southern Amazon sites that really focused on trying to organize, fighting very hard against a very powerful undercutting that’s happening, not only in the company, but in the state. I hope they continue that fight. It’s no accident that Black workers are very active in Long Island. It’s no accident that workers are very active in the UAW strikes. It’s no accident that they are essential to the UPS success that I’m excited to hear about. It’s no accident. It’s no accident that the largest group of Black unionists in the South are Black workers. The largest group of unionists in the country is Black workers, and yet we know that Black workers are living in the South in over-represented numbers, like dock workers. There’s all these historic unions that are still in place across the South. Black postal workers are still organized in unions, they’re fighting against whole states that are really bent and determined to undercut union activism. And yet here they are. So when we don’t talk about Black history we are missing part of the story of this moment with unions. If we just keep thinking, “Oh, this is about white workers,” we’re missing those connections.

Hagopian: Thank you so much, Dr. Kelley. I really appreciate this conversation. I’ve learned so much from your book and from this conversation tonight.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Audiogram

Blair L. M. Kelley explains how Pullman porters organized against their own exploitation and advocated on behalf of Black workers throughout the country.

Resources

Many of the lessons, books, and other resources recommended by the presenters and participants.

Lessons

|

It’s a Mystery — White Workers Against Black Workers by Bill Bigelow and Norm Diamond Lessons in Solidarity: Grady Hospital Workers United by Larry Miller Poetry of Defiance: How the Enslaved Resisted by Adam Sanchez Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union: Black and White Unite? by Bill Bigelow and Norm Diamond Teaching a People’s History of the March on Washington by Adam Sanchez Teaching The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks When the Impossible Suddenly Became Possible: A Reconstruction Mixer by Adam Sanchez and Nqobile Mthethwa

|

Books and Articles

|

In addition to Black Folk: The Roots of the Black Working Class, the following readings were referenced. Civil Rights Unionism: Tobacco Workers and the Struggle for Democracy in the Mid-Twentieth-Century South by Robert Rodgers Korstad (University of North Carolina Press) Claiming and Teaching the 1963 March on Washington by Bill Fletcher Jr. (as part of the If We Knew Our History series) Pies from Nowhere: How Georgia Gilmore Sustained the Montgomery Bus Boycott by Dee Romito, and illustrated by Laura Freeman (Little Bee Books) The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks by Jeanne Theoharis (Beacon Press) Right to Ride: Streetcar Boycotts and African American Citizenship by Blair L. M. Kelley (UNC Press) To ‘Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors After the Civil War by Tera W. Hunter (Harvard University Press) The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class by David R. Roediger (Verso) |

Films

|

Eyes on the Prize: America’s Civil Rights Years, 1954-1985, a film produced by Henry Hampton The Killing Floor, a film directed by Bill Duke 10,000 Black Men Named George, a film by Robert Townsend |

This Day In History

The dates below come from our This Day in History collection, which contains hundreds of entries all searchable by date, state, theme, and keywords.

|

April 5, 1866: Black Grocers Protest Taxes Supporting Confederates July 19, 1881: Atlanta Washerwomen’s Strike May 14, 1913: Longshore Strike in Philadelphia Nov. 22, 1919: Bogalusa Labor Massacre, Attack on Interracial Solidarity Aug. 25, 1925: Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters April 3, 1934: Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union Jan. 25, 1941: A. Philip Randolph and March on Washington Aug. 28, 1963: March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom March 18, 1970: Postal Workers Strike |

Participant Reflections

With more than 220 attendees present — including “a proud great grandson of a Pullman porter who migrated from Alabama to Chicago” — the conversation and chat was lively, engaging, and full of history, teaching ideas, and more. Here are more comments that participants shared in their end-of-session evaluation.

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

The history of strikes today rests with Black history; Black washerwomen were the first stay-at-home working mothers and it was the first time they were able to care for their own kids themselves.

The importance of disrupting the false notion that the working class is white, and the enormous value of loving and documenting Black workers’ contributions. For example, today’s Southern labor movement being rooted in Black communities.

I was really struck with the idea of just how important the work and labor of Black people is throughout U.S. history. I really want to get Dr. Kelley’s book and learn more. I was so happy that my breakout group had people who had washerwomen and Pullman porters in their families (parents, grandparents).

Black washerwomen in Mississippi organized themselves in 1866, one year after slavery ended, to demand a living wage. And they did it by themselves; they didn’t need an outsider to come and tell them what they needed.

So much. . . how to choose one? I think learning about the washerwomen organizing a union in 1866 was just awesome in changing how I think about who organizes labor unions — who did then, and who can now.

The most important idea I learned was the agency that Black workers took in realizing their power even in the face of persistent legal and extralegal barriers.

A quote that Dr. Kelley said that resonated with me was that “[Black people] were a community of survival and resistance.”

The collective power Black women had and shared with others to create unions and more!

During WWII, Black women worked in domestic jobs which allowed white women to work in the defense industry. However, this work was often unsupervised and was exempt from social security, unionizing, etc.

The resistance and creativity that Black washerwomen and Pullman porters utilized.

Black women have a long history of organizing workers to improve people’s working and living conditions.

What did you learn in your breakout room?

In my discussion group we talked about the importance of not just celebrating Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks. This really stuck with me because I feel like in schools today these are the only two Black people that children learn about. You may have to teach outside of the textbook to gain other important perspectives.

Thank you, room 35. We had an awesome discussion! T. J. Whitaker invited several of his students and they joined in the conversation. They are some great young people! Enid, you can say you met real students who are in AP African American studies and two teachers! Spread the word — this course in not going anywhere but up!

In group 16, we highlighted how certain jobs are ‘assigned’ to certain racial groups, focusing on the liberatory aspect of Black workers, not just victimizing Black people or celebrating Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks.

Group 34! Michigan teacher has to strategically place books on their desks to illicit questions about it from students, and then use those questions as pretext for teaching this “banned” history. Happy to hear their commitment to teaching truth!

Thank you breakout group 24! We talked about the power of telling the stories of everyday people, compliance and defiance, and how Black workers set precedents. One of our members shared about how unions were always talked down on where they grew up, and wondered about the connection to racism, and how unions were outlawed in the south. Another member shared about how his parents who were born in the ’40s who were sharecroppers and started working around 6 years old. The power of bringing our family histories in and connecting to the larger collective history.

Shout out to room 14 — Karin, Alexis, Karina, and Rhonda and the engaging conversation we had! We are educators in ELL, high school U.S. history, special education, and a retired teacher who is now a full-time substitute. We discussed personal connections of our family lineage who were the very workers who are being lifted up tonight by Blair Kelley. We spoke about validating BIPOC folx as the working class, not just white folx. We spoke about expanding our instruction to include the narratives of the Black working class because our students do not get to hear this. In fact, Rhonda shared how her grandson, who goes to college in Tennessee, is in a district that is teaching Black history now for the first time! Breakout room #14, thank you for such a fruitful discussion!

What will you do with what you learned?

I teach English, but all history is narrative; using these stories helps model writing and connects students to their personal and community histories.

I’m going to share these stories, particularly as examples of whose stories we are not hearing. What might they be? Why might these stories not be well known?

I will include more discussions of types of jobs and organizing of Black Americans during Reconstruction and the Great Depression.

We do not teach about the working class and the important role of the working class, let alone the Black working class. Nor the spirit of resistance of which Dr. Kelley spoke. I will bring this history to my students.

I will keep sharing all these new stories in my classes and in my union.

I plan to share with fellow educators, on my social media, and with my children and family.

I’m going to integrate this information into my science classes to show how Black people, and Black women particularly, keep this country running, and also how Black workers are the inventors.

I’m excited to have new layers to add to the curriculum, balancing stories of “real people/workers” with the timeline of government actions. Especially the early washerwomen unionizing story and the postal workers.

This has broadened my knowledge, which I will be able to share with my first graders. Bringing a positive light — the lasting collective work done, despite the many challenges they came up against.

I really enjoy talking with middle schoolers about their creative and resilient ways of being resistant in school, and I’m now thinking about sharing these stories of resistance and resilience. I hope that they can place themselves in this thread of history, survival, and joy.

Presenters

Blair L. M. Kelley, Ph.D. is the Joel R. Williamson Distinguished Professor of Southern Studies at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and the director of the Center for the Study of the American South, the first Black woman to serve in that role in the center’s thirty-year history. Kelley is the author of two books. The first, Right to Ride: Streetcar Boycotts and African American Citizenship (UNC Press), was awarded the 2010 Letitia Woods Brown Memorial Book Prize from the Association of Black Women Historians. Kelley’s newest book, Black Folk: The Roots of the Black Working Class (Liveright), was awarded a 2020 Creative Nonfiction Grant by the Whiting Foundation, and the 2022-23 John Hope Franklin/NEH Fellowship by the National Humanities Center.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing, and on the staff of the Zinn Education Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn