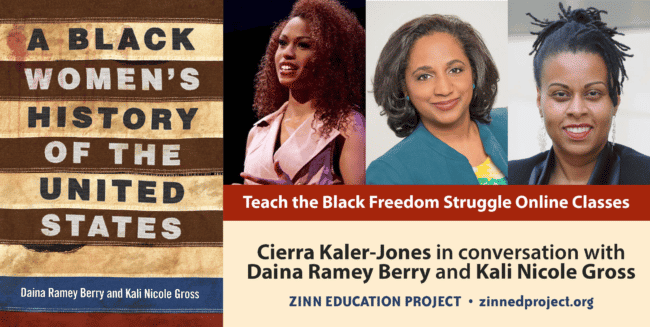

Over 300 educators, organizers, parents, and students joined the Zinn Education Project’s Teach the Black Freedom Struggle class on March 8, 2021 (International Women’s Day) for a conversation between the authors of A Black Women’s History of the United States (Daina Ramey Berry and Kali Nicole Gross) and Education Anew Fellow Cierra Kaler-Jones.

Here are a few reactions from the participants:

One of the most important ideas that were reinforced was the agency of Black women in the Americas from the 1500s to the present. There is a continuous lineage of Black women who fought for themselves and their communities to have better lives.

I appreciated the conversation and discussion around removing women from the margins and boxes of earlier textbooks in the process of centering them in history.

I did not realize how much of the Black perspective I used in the classroom was from the Black male perspective and left out such a key component of the Black experience in America by not directly placing Black women as central roles rather than a tangible connection.

I’ve been forced to sit through so much PD that has been derivative, repetitive, or basic. Not this. This class really helped address issues I’ve been wanting more education/training on that I can apply to my classroom!

The history of Black woman is the history of how our country has failed to protect us. However, it is a roadmap to resistance and a framework of where this country needs to go moving forward.

Black women’s history starts before 1619 and starts with freedom, not slavery.

Harriet Scott’s story — as a highlight of how often women, and women of color, are REMOVED from stories.

I loved the way that Dr. Berry and Dr. Gross brought transparency and humanity in telling the stories of their collaboration and writing process.

Below, find highlights of the session, a full video recording, recommended resources, and more participant feedback.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Cierra Kaler-Jones: Welcome to everyone, on behalf of the Zinn Education Project, for our class on A Black Women’s History of the United States. Happy International Women’s Day from us today, too. How beautiful and how powerful it is that we get to share this virtual space, especially today. Some of you are joining for the first time and some have participated in our spring series, and some of you have participated in all of our online classes. It truly is a gift to be able to share this time together and I thank you for being in virtual community with us. My name is Cierra Kaler-Jones, my pronouns are she and her, and I’m the Education Anew Fellow with Communities for Just Schools Fund and Teaching for Change. I’m also a community-based educator and a PhD candidate at the University of Maryland, College Park.

The Zinn Education Project is hosting this session today and offers free downloadable people’s histories lessons that many of you have used. I’ve used many of them myself for middle and high school classrooms from the Zinn Education Project website. We have a campaign to Teach the Black Freedom Struggle, and this online class is part of that larger campaign. Today we are joined by ASL interpreters Krystal Butler, and Tyriibah Royal. We’re so grateful to them for being with us and for interpreting this conversation this evening.

So, before we begin our conversation, we want to find out who is in the room and go through our plans for our time together. We’re going to do a quick poll to find out how many teachers, librarians, teacher educators, historians, parents and caregivers, students, and others who are in the room with us. Many of you are in multiple roles, so please just pick your primary one. We will post a poll, as you may see on your screen, for you to respond to. If for some reason technology is not working for you and you’re not able to see the poll, please do continue to introduce yourself in the chat box. We’d love to hear from you and we are glad that you’re here. Throughout the session, we want you to use the chat box to post questions, comments, resources, and ideas. We will read your questions and our guest speakers will try to respond after the breakout rooms. We will do our best to answer as many questions as we can in the time that we have together. We’ll also do a short evaluation at the end.

Please continue the conversation on Twitter. We encourage you to share your learnings and your insights using the hashtag #TeachBlackFreedomStruggle. Now I think we’re ready to see the poll results to see how many folks are in the room with us. Wow, we have 56% educators, 18% teacher educators, 7% students, 2% historians, 4% community or labor organizers, 2% primary family members, and 10% others. Thank you all for being with us.

We’re now ready to start our conversation, and I am really excited about this. I’ve been looking forward to this ever since I had the opportunity to read A Black Women’s History of the United States. So, let’s just jump right in. After about 30 minutes, we’ll pause so that you all have an opportunity to meet one another and talk in small groups to share your thoughts with one another. I am happy to introduce Dr. Daina Ramey Berry, history professor at the University of Texas at Austin, and Dr. Kali Nicole Gross, a professor of African American Studies at Emory University, and the Martin Luther King Jr. Professor of History at Rutgers University. Go RU! They are the co-authors of A Black Women’s History of the United States. If you do not have this book, I’m telling you, it is a page-turner. I couldn’t put it down. So I’m so thrilled to be able to dig into this conversation and ask you some questions that I have that came up in the book. So, let’s jump right in. While the dominant narrative in many history textbooks begins Black history in the United States with enslavement, your book actually begins before the 1600s and discusses how the first Black women who were on this land were not enslaved. So, what does the dominant narrative miss or leave out when it begins Black women’s history in the United States in 1619?

Daina Ramey Berry: First of all, thank you so much for having us. We’re thrilled to be here. Our goal was to show that Black people were free before they were enslaved. Let me put it simply: Black people did not only come here as enslaved people. Their role in the early history of what became the Americas was not solely about enslavement. It was also about movement, about travel, about independence, about freedom. And we really wanted to start the book off like that.

Even the people of African descent that came here beyond 1619, and some of them that came enslaved, were free people before they were captured and traded and sold into enslavement. I think that’s a very important distinction for our young kids, and for teaching younger learners to understand that so that Black people are not seen from the beginning as people that are captive and that have no agency, and that are responding to and reacting to that captivity. Black people were free first. So it was really important for us to start with Isabel De Olvera as a free woman of African descent who comes here demanding justice, who comes to what becomes the United States (it was New Spain at the time) and to come here on her own, and to travel here on her own. We felt like that was really important. I’m sure my co-author, Dr. Gross, would add a few things to that.

Kali Nicole Gross: I actually think you’ve covered it all really well. I mean, it definitely was super important to begin a narrative from this different place. That sort of proclamation, that demand for justice, really is something that motivated us to really look at the ways that Black women can continue to fight for and demand justice throughout all of the periods of study. That definitely became one of the throughlines throughout the book that I think actually runs right up to today.

Kaler-Jones: That actually is a really great segue into my next question, because one of the quotes that I pulled from your book — and even just thinking, Dr. Berry, you had named Isabel De Olvera — and just that beginning quote in the book, “I demand justice.” I got chills reading that. Another quote that brings me to this moment in conversation is, you say, “Whether challenging segregation in education or in public spaces, Black women and Black girls are on the front lines, where new laws were translated into change and daily practices. While Black women throughout history have been over-policed and under-protected, there are many ways that Black women have always resisted oppression and fought for justice.”

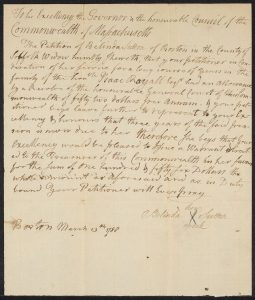

You talk about Isabel De Olvera’s petition for a document that protected her before she even embarked on a journey with Spanish explorers. You talk about Mumbet who worked alongside an attorney to win the first successful freedom suit in Massachusetts history. We’ve talked a lot in this series with Dr. Jeanne Theoharis and Jesse Hagopian about Rosa Parks, and how Rosa Parks supported Ms. Recy Taylor and Gertrude Perkins in their cases against sexual violence. So, can you highlight for us some of the stories of how Black women have pursued justice through the courts and/or by speaking on their experiences publicly, despite backlash? Dr. Gross, you want to start?

Nicole Gross: Sure, I’ll start. I’d like to start actually in the post-Emancipation period, if that’s okay. One of the moments that sticks in my mind is certainly just after the Civil War, and after the riots in Memphis in 1866, you have huge swaths of the Black cities communities destroyed brutalized by anti-Black violence. Particularly a lot aimed at Black Union soldiers and people who were affiliated with them, but also a number of white police officers and white folks just sort of decimated this community. In a part of that process, they also waged a reign of sexual violence against Black women.

There was endemic rapes that also occur during this riot, and one of the things that’s so powerful about it, is afterward you have five Black women who testified before a Senate committee to talk about those experiences and to go on record and say that they did not consent. It was a huge deal at the time, because it was really one of the first times that Black women were able to legally lay claim to their own bodies and say that they did not consent. It’s not that that was the first time that they tried to do this — you certainly have like examples of Celia, an enslaved Black woman in Missouri in 1855, who, after being serially raped by her owner, actually kills him and burns him in a fireplace. During her trial they try to advance this defense that she was trying to protect herself against these attacks, and the court basically finds that she’s not entitled to do so. She ends up condemned to death. So, that’s this moment during enslavement.

Then we have this post-enslavement period where you have these women go on record and say they don’t consent before the Senate committee, and have that being recognized. So that’s two examples, I think, during enslavement. Then immediately after, and it isn’t just around sort of sexual violence, you also have these instances where — and we actually talked about this before — but Black women also have protested things like segregated busing. Even before we have this historic march, you have Black women like Viola White refusing and being arrested in the 1940s and actually trying to appeal that conviction and dealing with horrible retaliation: her daughter’s being brutally, sexually assaulted by police. They retaliate. They basically stole the case. So it just doesn’t go anywhere in the courts.

But then, ten years later, you have five Black women come together under Browder v. Gale to once again run up that hill. And they go through, this time, the district court to, again, try to protest this segregated busing. Finally, they actually get a win that helps to end segregated busing in Montgomery. So, those are just some of the examples of these places where you have Black women going to the courts and using them. It’s not always certainly a win.

But one of the things that I’m just in awe of is that they’re not deterred. That’s not to say that they aren’t discouraged, that there isn’t frustration, heartbreak, and disappointment. Because I don’t want Black women to come off as superhuman either; I think that denies their humanity. If we try to make them seem like they’re just heroic, and no matter what they just keep forging through . . . no, I mean, Black women have continued to fight, but a lot of times it is at great cost. But one of the things I do remain in awe of is that even when there are those hurdles or those obstacles, you do have folks who will regroup and come back and continue to try to push forward.

Ramey Berry: I was putting some resources into the chat of some of these freedom suits during slavery, websites that I use all the time that I share with other educators that I think will be really useful, where you can pick and choose different stories that you can share with your students. Some of these women we talked about in the book, like Linda Sutton, we talked about her, we opened up one of the chapters with her. Then there’s also a number of freedom suits from women in and around DC. Those are really interesting stories. There are some really, really wonderful resources there where students can actually look at these primary documents and see how Black women were fighting for their freedom.

I think what Dr. Gross brings up is really important. She’s showing that this is a battle that’s ongoing, and we’re still seeing it. I mean, you could even bring that up to someone like Anita Hill, fighting for her own freedom of work in the workspace and to be treated respectfully. There’s a number of women that we can talk about, contemporary women, that are here now that are fighting for freedom. So I think it’s important to define those kind of broadly, like we do in the book. And also think about the large spectrum or continuum of these battles to fight for freedom and equality that we see and that we tried to highlight throughout the book. Also, I think of famous people like Sojourner Truth. She’s fighting for freedom and also the freedom of her children. She goes and gets her son who was taken away and goes and testifies in front of a grand jury to get her son back. It took almost two years for her to do that, but that’s something that we also highlight, this level of motherhood activism, of moms being activists, fighting for the rights for themselves and for their children, and that is another theme that we talked about, all the time periods in the book that I think would be useful for students to think about.

Nicole Gross: Yeah, 100%, the only thing I would just chime in to say, and this is jogging my memory, when Dr. Barry mentioned the continuum of Anita Hill, it’s thinking that some respects that we also need to understand her along this continuum of Sandra Bundy, who was one of the first folks who basically sues in 1977, in DC, the Department of Corrections, because she had been repeatedly sexually harassed on the job. So in 1977, that case was a real long shot, but they actually won, and it helps us create the legislation to have sexual harassment on the job be considered a part of sex discrimination in the employment place. That’s some of that context for how we then get up into 1991 with Anita Hill. So, thanks for that question. Great question. Hopefully, these muddled answers are helping.

Ramey Berry: I would love to just take a quick moment to thank all the teachers here because I know the work that you’re putting in is not always rewarded. You’re putting yourself at risk, and you’re having to be creative, and you’re having to spin on a dime. So we just want to commend you and thank you for the hard work that you all have been doing since about a year ago today. The policies have had to change and we’ve had to just move and change. We’re teaching at the college level, but we know that you teach our children. So, we just want to both thank you for what you’re doing and what you continue to do. We both have school-aged children, so we understand. My child is tired of Zoom as much as I can be sometimes, but I can’t imagine with you all having to create lesson plans and find all kinds of ways to creatively engage your students. So thank you. I just wanted to say that.

Kaler-Jones: My heart is bursting with so much joy at all the teachers that consistently show up to these conversations that teach people’s history in their classrooms and at home and in their communities every single day. We are so, so grateful. Absolutely.

One of the things that I just want to highlight, that you all have illuminated for everyone, and one thing that is so, so clear in the book, is the continuum. Even as you’re sharing these different stories, I’m thinking about moments in the book where I was like, “Oh, I never knew that,” because it was all on a continuum. But the stories oftentimes don’t get uplifted. So, I’m thinking about the story that you share about Harriet Scott, Dred Scott’s wife, [who], if I’m correct, the name was taken off of the case when it was repealed. Thinking about these moments in time, where Black women have been truly at the helm, but then erased in these very tangible, visible ways. I’m thinking about how this funnels into the next question about how throughout history, Black women have faced misogyny and sexism, even in organizations and movements aimed at Black freedom and liberation — such as the March on Washington — and were brushed aside by white suffragists who believed that they were better suited for the right to vote than Black men and women. So, can you talk about some of these moments in history where Black women’s voices were largely left out in movements, although they played critical roles in organizing and sustaining these movements for freedom?

Ramey Berry: Absolutely. I’ll just start off briefly looking at the suffrage movement, particularly because we hit the anniversary this year. A lot of people did not recognize or didn’t know the work that Black women were doing. They formed their own suffrage clubs because they tried to fight with the suffrage movement, with white women’s organizations, and were often marginalized. We know that Ida B. Wells was told to march in the back of the parade, although she had been organizing with a group of other Chicago women, and she refused to do that. So what we find is that Black women develop their own organizations and they also work with white women and other organizations. But when they didn’t find that their issues were being treated as paramount, and as equal to white women’s challenges, they then formed their own organizations. But they also felt discrimination within their own community, and we see that and I’ll let Dr. Gross talk about some of that. But we see that within the Montgomery Bus Boycott Movement, we see that in Shirley Chisholm’s campaign for presidency, and we talked about Black woman and intersectionality, and how their experiences hinge upon a number of ways where they intersect as women, as female, depending on their sexuality, all kinds of different ways in which women, whether or not they’re differently abled, there’s a number of different factors that Black women have to keep in mind that they’re serving. And they can’t always, and we don’t choose one over the other. So you see that coming out within activist movements as well. So I’ll let Dr. Gross go, I know she’s got lots of great examples on this.

Nicole Gross: I actually want to give context to the two that you’ve mentioned, because I think it’s important. When we think about the Civil Rights Movement, there is this way that Black women get written out. Either it’s this singular focus on Rosa Parks — and I think Dr. Theoharis’s work does a brilliant job dislodging that whole sort of exploiting that myth to really demonstrate this decades long legacy of grassroots activism, of challenging rape and working on all these . . . Just an incredible, phenomenal freedom fighter for decades, not just someone who got tired and decided to stand up by sitting down one day and this sort of thing. But even with that aside, the fact is Black women have been strategists and foot soldiers, organizing.

The bus boycott is one of those examples, but also, I mean, we know that they organized throughout, things like SNCC — I know we have some folks from SNCC here. So these are the other examples where you have Black women who are at the forefront of all of these movements. Then when you do have these moments like the March on Washington, where there’s this recognition, like they’re allowed to be there but they don’t want them to make a speech, and someone’s giving them this canned speech. But even then I feel like there’s a way in which even in reading that, they lay claim to the same, like, there’s a fire to me that comes out in spite of it.

So that one moment, and then again, there are women like Shirley Chisholm, who had this audacity to just really push past so many different things. Even before she does this heroic run for the presidency, she also had to contend with all kinds of racism and sexism. When she was beginning her political career people had chided her as being a little school teacher, like who’s interested in even interviewing you when you’re running for these roles? But she knew how to organize: she grew up, worked her grassroots networks, mobilized her community, met people outside of projects, shopping centers, supermarkets, you name it. She really put that foot to the pavement and basically pulled out a win, which was like this major upset. This is even before she runs for the presidency. Even then, as pretty much like a protest candidate, but really calling attention to these issues that impact Black and Latinx communities, poor people, working class whites, all the rest. You still had contingents who were uneasy about her taking on that role, and that was among folks, even the Black Caucus, not being able to get behind her. The Black Panthers were able to support her presidency, but these other folks were not. Because the idea was that she would never win; but none of you all would either, like, why not get behind her presidency? It was against Nixon, but at the same time you had white feminist organizations also being apprehensive about how far to take their support of her campaign as well.

So there’s this way in which Black women’s activism has always been at these difficult intersections. I think one of the things that we balanced out with the book is trying to — usually I’m the person who goes to the dark, the morbid side if I’m faced, so I feel like we want to have truth, that we can’t run from the ugliness and the pain. But at the same time, I also realize, if anything, in learning and doing these histories is that there’s a particular way in which sisters have learned how not to rest in that. As disappointing as some of those sexist and misogynistic lack of support actually is, they still organize collectively and work well with each other to continue to move forward and to do incredible things. I mean, one of the things I still am in awe of is when they teamed up with the senator from Massachusetts to try to push back against the ways that Black voters were being disenfranchised during the 1920s. I still think it’s a brilliant idea, that they were trying to get congressional reapportionment to be based upon the number of ballots cast, not the number of people in the state, as this way to combat voter suppression. Of course, this act goes down in flames. But still, I think it was a brilliant idea, Black women work with him on this, help canvass and get testimonies of people to talk about the ways that they’ve been disenfranchised. They don’t necessarily get credit for helping architects of this bill, but they absolutely were. So those of these spaces where I find that I’ve been resting a lot more and thinking about how I am looking at this history.

Kaler-Jones: I love something that you said, Dr. Gross, about emphasizing the fire. It reminds me of one of my favorite Ella Baker quotes, “Give light and people will find the way.” I think that that’s what Black women have always done, is given off this fire, given off this light on this continuum that you highlight so powerfully for us in the book. Earlier, we were talking about the importance of providing nuance and complexities in Black women’s experiences — not just thinking about, as you just said, the pain, but also about the power, about the art. One of my favorite aspects of the book, being an artist myself, is how Black women have always used art. Black women have used art, from hair, you talked about the takedown laws, to poetry, to visual arts, to dance, to music, and so much more as mechanisms for truth telling, resistance, and also for healing. So, can you speak a little bit to Black women’s art as a tool for understanding what you call Black women’s inner lives?

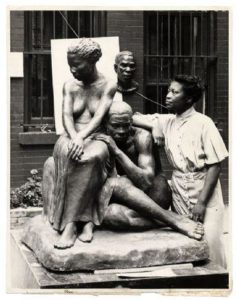

Ramey Berry: That’s a great question. I mean, we covered Black woman artists from every time period in the book. So many people know about Phillis Wheatley and her poems, and what we learn about art — whether visual art, music, painting, sculptures — it’s a form of expression. As a historian, it’s another source to understand a person in a particular time period. So, for us, it just adds another layer of texture to understanding Black womanhood and/or the things that were important to that particular woman. We talked about people like Augusta Savage. We talked about other artists that were making changes and looking at art as a way to express themselves and to find a space for themselves in society. I think that was really key for us throughout the book.

Nicole Gross: I would just add that there are a couple of artists that we want to highlight. Certainly, like I said, queer artists. Edmonia Lewis in the antebellum era, she’s a sculptor, but she also is really deeply impressed with, and ensconced with these ideas around abolitionism. She also makes these medallions of prominent abolitionists. This way they would turn art into this political expression, but also thinking about performers as well. Even early performances like Sissieretta Jones, who is performing in the 1890s. She actually performs in the White House at certain points, but she also travels abroad diasporically. That was the thing that I was blown away by: she formed her own troupe, they performed throughout the Caribbean and certain parts of South America and Guyana. My family’s from Guyana, so I had to, you know . . . She goes abroad and performs and has just this incredible career.

Again, Augusta Savages, this was a woman who remade herself from being married really young and having a child to finding a way to lose her husband, take her kid, move to New York, study at Cooper Union, reinvent herself, start referring to her daughter as her sister — she just kind of remade herself in the city. But she also embraces Black nationalism. She helps to democratize art by organizing and creating whole art centers that are aimed at teaching anyone who wants to know about art how to become an artist, and just making it accessible for Black people. This is a brilliant, brilliant kind of mind. But even Black women writers, we talk about Zora Neale Hurston, and Ann Petry, who are getting at Black women’s interiority. Also the complexities about life and racism in the urban north.

Then there’s the Black queer performers from the Harlem Renaissance era. It’s interesting, I teach students in classes, and we look at some of the lyrics and hip hop, I guess they are problematic, deeply materialistic, violent, and vulgar, but they had their rivals in the 1920s, too, where you have certain lyrics that were also really sexualized and vulgar, explicitly intriguing about getting drunk and high and bathtub gin and cutting folks with razors during fights. So there’s a way in which there’s this trajectory, and on the one hand, at certain points it is problematic, but it does also open up a world and a window onto Black life and culture in its vibrancy and its complexities in a way that’s not just always referential to whiteness. That’s one of the things that I love about Black artists and Black art is it is both political and it’s completely cognizant of white supremacy and anti-Blackness. There’s no question about that. But they still find a way to root it in the Black experience. Even when these blues women are singing, some of them are talking about black eye blues, they’re talking about domestic violence, and other kinds of issues. There’s this way in which they use these platforms to talk about some of those issues. Sometimes they talked about arrests, they sing about poverty. These are spaces that are about sounding some of those hard parts of life. There is this way that I think promotes healing by exorcizing some of those demons. At the same time, they take some of those hard, ugly experiences and weave it into something beautiful.

Ramey Berry: I would just add, this was completely going a little bit further back, I just put a few things in the chat of women seamstresses, and that’s a form of art. It was a skill that the Black women had that gave them different kinds of freedoms and that gave them access to other aspects of society, whether they were in slavery or in freedom. So, for those that are teaching younger children, Grace Wisher, who helped make the first Star Spangled Banner flag. We also have someone like Elizabeth Keckley, who was a seamstress in the White House. These are just two examples of other forms that I would consider an art form or expression or a skill that Black women had. And they use that when they use that to express themselves, but also when you look at Black women that were fighting for freedom, a number of slave women who self-liberated — that’s what I say instead of saying running away; I don’t like to call them fugitives because they were stealing a freedom that was stolen from them. So I like to think about them as women that are liberating themselves from captivity that they were illegally brought into. A number of those women that had been seamstresses took the dresses that they made and produced because they felt like those were their own. And oftentimes, they took them not only to blend into free society, but also because they felt like it was rightfully theirs. There’s a certain level of pride that they had in the craftsmanship of making these dresses, and I just wanted to add that although that jumps way back into the antebellum and colonial era.

Kaler-Jones: There are so many rich stories in the book and in history, and as you’re talking about the different ways that art has been used by Black women throughout history, I just am always so in awe of thinking about the Tignon Law, where Black women, women of color had to wrap their hair to signify that they weren’t part of a “lesser class.” Then, instead, they were like, “We’re going to wear the brightest fly garbs with beads, and we’re using this as a form of resistance, and standing in our most authentic truths in ourselves.” So, I’m always brought back to that moment in time in thinking about how you all have illuminated the continuum, about how that shows up today through racist and sexist dress code policies that continue. And yet we still continue to resist.

So, one thing that you all brought up that I want to make sure to highlight here, too, is lifting up the queer and trans women that you talk about in the book. The book notes that narrow gender expectations for Black women have been another form of oppression. I think of the stories in the book that highlight Gladys Bentley, Pauli Murray, and Marsha P. Johnson, and how they defied rigid social constructions of gender. Can you lift up some of the stories of the queer and trans folks that are often left out of textbooks?

Ramey Berry: I would love for Dr. Gross to tell the story about Francis Thompson because this is actually . . . I mean, can we nerd out just a little bit, though, and talk about the discovery of the record. I know that that might not be something that everybody appreciates, but it’s in the book, so there’s such a larger story. I think it’s important, like even with Isabel de Olvera, to find her story took us a year. We were learning about it, but we spent a year doing research to flesh that chapter out. And this other story about Francis Thompson, I think, is really, really well and that was your research find.

Nicole Gross: I’m trying not to nerd out. We’re trying to help the teachers, not go on a geek trail with me, but I’ll see how we’re doing timewise. Francis Thompson, it’s a really important story, because Francis Thompson, I mentioned actually, is one of the women who went on record to testify to being sexually assaulted during the Memphis Riots in 1866. As a result of that testimony, she became persona non grata among local authorities. She’s routinely harassed and she gets questioned and she’s on suspicion for everything from renting a house of disrepute to supposedly illegally selling “hoodoo bags.” You name it, they had accused her of everything.

In 1876, more serious allegations really started to dog her. This idea that she is actually a man in woman’s clothing, that she had been able to elude those suspicions for a long time. And in 1876, she actually is arrested and subjected to a series of invasive examinations, in which they proclaim that she is, in fact, biologically male. She is arrested for cross dressing, even though she maintains that she is a double sex, and lived her life for at least the last 20 years as a woman. She was imprisoned. Initially, she was forced to labor outside as a part of that sentence. So people would come by and ridicule her and ask her rude questions about her gender, to which she would respond, “None of your damn business,” and she would maintain that fight. Again, it’s at great cost; she survived her sentence, but she took ill shortly thereafter and died in November of that year. It is this important story too, because I think it sketches out this beautiful phrase.

I was on a panel with a transgender prison activist CeCe McDonald, and one of the things that I remember her saying was that she really wanted to know more about her trans history. It was something about her saying that, that turn of phrase, it made me realize that I had come across a number of cases throughout history that might be able to fit or sketch out that, along that continuum. So telling that story and others like it with respect to Gladys Bentley, certainly Pauli Murray, and Marsha P., of course, is phenom and Edmonia in the antebellum era. It was absolutely necessary to have those stories be included, and throughout history, not just until we get to like 1990 or something.

But with respect to my nerd trail, I would have been longing to find some image of Francis Thompson. It’s 1876, she’s an ex-enslaved woman. So the chances of me finding anything, no, I just happen to go online looking for Francis Thompson, anyone who has documents, eBay pops up, I never used this site, really, and lo and behold, someone’s selling a copy of a paper The Day’s Doing. It’s a rare paper, and they actually have 1876. I look it up and lo and behold there are these engravings of guess who, Francis Thompson in 1876. My friends could not believe it. So that is how Francis Thompson’s image was able to be in the book. And it’s under an article which says, “Francis”, with an “is” instead of an “es” and this sort of thing. Some of the captions are like “the Negro man who lived as a woman for 20 years.” So, it was an incredible find, to be able to even see some sort of image of her, one of those finds in history that you’ll just never forget. And that was my geek trail.

Kaler-Jones: One of the questions that I have for you all is thinking about who are some of the lesser known women in the book that you would want educators specifically to learn more about and teach their students about? There are so many incredible women in this book, so if we were to think about some of the women that we would want to highlight in our classrooms, who would you like to uplift in this moment?

Ramey Berry: I always say we have questions. Some of this, I always say that there are so many women that we mentioned in this book, women and girls at various ages, and depending on what age group you’re teaching, it seems like it’s really an opportunity to focus on someone that your students might relate to. But for me, Mary Colbert, who was a young girl; we opened up in the Civil War chapter, where she was hiding some of the family jewels in her apron. She made a statement that was so powerful. The troops were coming through and looking for the family jewels and riches, and they hid them in her apron, and no one even looked at her. She said, “No one even looked or took a second glance at me. They didn’t even know that a little Black girl was holding all the family heirlooms.” I think that was a really powerful moment for us as scholars of Black women’s history, to think about how Black women have often been overlooked and ignored when they’re in spaces that are very public. I think that’s one of my favorite stories. But there’s a ton of other women that Kali and I kept in the book — unnamed women, women who we didn’t know much about, but we knew something that they did historically. That was amazing. And we felt like even if we didn’t know their names, their stories were very important for us to continue to tell. So that would be my response to that.

Nicole Gross: Thanks, this is a great question. So, I have ones that I usually do, but I think that I’m going to try to branch out a little bit. I actually got to talk about Callie House, who is one of these early forerunners of the Reparations movement. Usually, when we think about Reparations, it’s like a very present-day conversation. Folks don’t realize that Black folks were organizing around this issue as early as 1898. House was herself formerly enslaved, and one of the things that she was horrified by was the state of elderly formerly enslaved people, how destitute they were. So, they started to organize collectively and they formed a national ex-slave mutual relief bounty and pension association to basically start to press for Reparations for all of these formerly enslaved people. And she canvasses the country and talks about it, they fundraise, they use the Postal Service. Basically she helps to really grow this organization from like 34,000 to over 300,000. But she also is basically criminalized for her activism. There are a series of agencies from the Treasury Department, the Fed, who are horrified at the prospect, so they basically get her on trumped up fraud charges, saying that she’s using the Postal Service to defraud people, because there’s no way this could be real and all the rest. So, she actually is in prison for about a year or so before she ends up becoming sick and passes away from cancer. But she is an incredible figure who I think is one of the . . . There was a book about her by Dr. Mary Frances Berry that came out, that’s a brilliant work. But she’s not like a household name, and she really should be.

That said, one of the other things too about the book in terms of resources, thinking about the educators, we didn’t have the language for it at the time, like a community history, but in some ways, that’s what this book was. I mean, we had a lot of sister scholars read our drafts and outlines and meet with us and give us feedback, and we relied heavily on their scholarship. We use their resources in ways that if people see something they’re interested in, there’s sites and footnotes, these are the places where you can go and follow up on these incredible stories. We also tried to cite things like documentaries, literally quote those that are readily available. These are also ways that you can incorporate those materials into your classes as well.

Kaler-Jones: I love that you bring that up, because reading that part of the book where you talk about the sisterhood scholarship, leaning on one another, coming together, reminds me a lot of our relationship with so many of the teachers that are part of this conversation, leaning on one another for lessons, for resources, for citations, for feedback. So, I would actually love it if you would share a little bit more about what that process was like for you all to bring so many different scholars together, and what did that look like in practice? Because it’s such a beautiful story from what I’ve read, so I’d love to hear it.

Ramey Berry: It was one of the most enriching days of our academic careers. We both have shared that. To have scholars of various generations, who were at different ranks and different types of institutions, ten Black women’s scholars all there all day at Rutgers University. Dr. Gross organized this and we gave them the manuscript. When I say manuscript, I’m using that term loosely, because some chapters were scraps of disjointed stories and outlines. Others were different stories that we wanted to tell, and sources, and others were full drafted chapters that were rough. We put ourselves in a rough, very rough . . . We were very vulnerable to have to share that. But we wanted to make sure that the stories we were telling, that we were telling the right stories, and that we were getting feedback from our peers, and people that were our elders — whose shoulders we stand on — to make sure that we were covering everything. There’s so many other scholars that are coming behind us that are doing phenomenal work in Black women’s history, and this field itself is probably the fastest growing field within American history. Do you want to say more about that day?

Nicole Gross: I would just echo everything you said, and just say it was really this incredible display of sisterhood. I mean, we spent hours talking about these issues, and I can tell you, I, we felt an immense pressure to try to get this right. I mean, we say at the outset, this book isn’t meant to be the end all be all, right? We’re hoping that our book will be the place where you start your journey in terms of learning about Black women’s history, not where it ends. So it’s written in that way, and we tried to use as many sources as available, primary sources, but also to highlight these other phenomenal works. Those sister scholars were cutting edge in their own fields; we had legends who read drafts for us, as well as junior scholars who just produced amazing scholarship. It was an incredible experience for me, personally, to be able to trust them with some rough, raggedy writing, and know that you aren’t going to be burned in effigy for it, but that we all really work together. Because I think everyone had a sense of the seriousness with which we were approaching this project, everyone wanted to do a good job and to find ways to really do right in telling Black women’s history. So it was a really powerful experience.

Ramey Berry: I just want to add one more thing. There was a question in the chat about our collaborative process and I think that kind of moves into that, if that’s okay. Because we were at the same institution when we first started the book, we were also working on our second single author book project. So this book took us about seven years to write because our individual books came out in between this process. But we spent a lot of time talking about themes, talking about structure, deciding who we wanted to cover, why we wanted to cover certain people, do we do a typical timeline, do we do a timeline that’s different because Black women’s history moves along a different schedule than other other forms of history? There was a lot of back and forth. Then when we were at different institutions, we would have phone calls, meetings, we’d meet up at conferences, we’d share versions of different drafts, of different sections, of chapters, and get feedback from one another, and send that out. Dr. Gross was really good at making sure, at the end, we would just get out different chapters of different scholars — this person is doing this work, let me have her read this, or we would just randomly ask folks, “Can you read chapter three?” “Can you read chapter six?” “Can you read chapter eight?” We really wanted to make sure that we were hitting all the marks right. That’s how I would describe our process.

Nicole Gross: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I would, again, echo all of that, and just say, Daina and I both, we are Black women’s historians and in certain ways we have specific kinds of expertise. I mean, mine was about Black women in the criminal justice system, as well as the latter half of African American history. But in order to do this work, we really reached out to a lot of sister scholars far and wide who are experts on targeted areas, because we wanted to make sure that what we had was correct, and that we were doing our due diligence. So they’ve graciously read chapters and gave feedback at the last minute. Then, also, in terms of the balancing aspect, I was saying before, I’m usually the person who goes to the dark side. I don’t want to sugarcoat anything. I want you to know every lash, every injury, every violent thing; I’m that kind of person. And, Daina, for such a heavy topic, is actually optimistic. Daina’s personality is different. So we have to really battle and figure out how to get the balance right. Daina had to talk me off the ledge a few times, like, we want people to read this book, not be beaten down or totally depressed by it.

Ramey Berry: Then when we sleep, we’re going to start off with a Black woman being murdered, like the story was this woman getting killed? And we’re like, wait a minute.

Nicole Gross: That was my passion. We want people to read past that first paragraph. It’s true. I don’t know that people would have read if it wasn’t, and it doesn’t mean that we didn’t include stories that were hard. Definitely they are there.

Ramey Berry: The slave trade and just descriptions of the Middle Passage, even having multiple chapters of the slave trade. That was a question: Why is the slave trade in chapters one through three? It’s because Black women were being brought over in all of those time periods. It didn’t just come at one point and dropped off. We wanted to reflect that, and that was hard. We don’t want to lose readers, but we also need to tell the truth.

Nicole Gross: Exactly. I mean, even the execution of Corrine Sykes in 1946, and Black women with special needs. Definitely those stories are there. But I do think we struck the right balance in that respect, and that came through the collaborative process 100 % with each other and with a broader community of scholars, for sure.

Kaler-Jones: On that note, I’m seeing a follow-up question in the chat box. As you talk about these painful moments in history you carry these stories with you, do either of you feel, in the carrying of these stories, the magnitude and weight and trauma from the research and learning about the stories that haven’t been told?

Ramey Berry: Wow, that’s a great question. I’m glad we’ll have time to answer it. We both write about Black women experiencing violent trauma, both in our own individual research. And we both experienced family loss: Kali lost her mother and I lost my father during the writing process, and that made it really raw to have our own personal loss, but be writing about other people’s losses. We were seeing violence and other forms of physical and sexual abuse and we were also writing about that. It was very difficult at times. There were times where we both couldn’t write. I remember, there was one time when she called me like, “I’m dry right now, I can’t get anything out.” And I called her back three weeks later, like, “I’m right there with you.” The deadline was extended; this book should have come out sooner, but we needed more time. So yes, we do carry it.

I have found ways, and everybody has their own way of doing it to try to, to successfully be able to navigate the heaviness of the research that we write about. Some days I’m more successful than others. Some days I don’t like talking to people, I just don’t like it. I’m just not in the mood, like I can’t, I’m full with whatever emotion because I’m carrying something so heavy, and I’m just not in the mood. Then there are other times where I need to work out, I need to go run. That’s what I do, I run. I also do totally mindless [things like] TV, which is why I’m looking forward to watching the Harry and Meghan interview after this, because I need to do something that takes me completely away from the realities of enslavement, which is what I spend most of my days in. So I need to get out of that and go completely far. I watch a lot of comedy. Those are some of my coping mechanisms. I’m trying to get back into yoga, which is what I did during graduate school, and meditation. Those are my methods.

Nicole Gross: Sure, and I understand you. Really quick, it is difficult, and there were times I’m also a mindless TV person as a way to try to escape it. I also sadly like to eat my pain, so I definitely gained some weight writing this book. Food and drink, Netflix, and all these things were my lifeblood. I’m not the type who will automatically go run instead, so it was — it is — difficult. It is hard, but it is also a part of . . . I don’t want to dismiss that because it’s real. But it also is like, look, it’s hard for me to write about it, but these folks lived it. And that is the other impetus where you have to kind of pull it back together and get back in front of the computer and find a way through. I mean, I literally transcribed Mamie Till’s description of what she saw the first time she looked at Emmett Till’s corpse, and I cried. I had to stop and take breaks and I just cried it out for a bit and then went back and then finished it. And I had to listen to it again. I was looking at it to make sure I got it right, because at the same time, I also really wanted to honor her and her words. If she could sit there and calmly recount this litany of horrible, horrific brutality against this child then I ought to be able to find it in me to make sure I transcribe it properly and cite that work. So it’s intense, but also somebody lived it.

I know we’re supposed to go on, but in the time we have left, we actually want to turn the tables just a little bit and ask you, Cierra Kaler-Jones, a question, because I don’t know if our audience is aware, but we are on the precipice of a newly minted PhD. Yes, she will be defending in a couple of weeks and her scholarship is very much, I think, related to the work that we do. So, I would love it if you could tell us a little bit more about that in the time we have remaining.

Kaler-Jones: Thank you, Dr. Gross and Dr. Berry. I’m going to have one more question for you both before we end, and I’m really honored to be able to share a little bit about my work. My dissertation focuses on how Black girls use art space practices like movement, music, hair, as forms of resistance to oppressive structures and systems, but also as identity construction. Together alongside high school age Black girls, my co-researchers, we created a virtual summer program and we explored Black history, Black feminist theory, community organizing, leadership, advocacy. Through the conversations that we were able to have in the program, we actually learned together how to code data and analyze data together. We actually took the transcripts from our conversations — they collected oral history testimonies from their loved ones — and we took all of that data, coded and analyzed it together, and they took the themes that they had pulled out from the data and turned it into artwork. And the artwork, they presented it in a community art showcase to their loved ones. I’m looking forward, in a couple of weeks, to sharing that. My dissertation is called You Can’t See Me By Looking at Me: Black Girls’ Arts-based Practices As Mechanisms for Identity Construction and Resistance.

I’ve learned so much from working with young people, just their brilliance that continues to shine, the hope, but also the way that they make connections. As we were talking about the continuum today, they make that continuum so clear in the ways that they uplift history. They actually wanted to call the showcase that we put on #HistoryRewritten because they wanted to center Black women’s experiences in history. So it feels very fitting to be able to have this conversation just a couple of weeks from being able to defend the dissertation, and I only hope that I can do justice to their words and to the work that they do. They’ve taught me, truly, about the principle of Sankofa, the Ghanaian principle of Sankofa, “go back and get it.” Knowing our history so we can know ourselves in the present, to dream ourselves in the future. And throughout the program, they created artwork that was worthy, they created futures that were worthy, in their minds, of Black girl brilliance. So, I’m looking forward to being able to highlight that, and I appreciate you all so much for putting me on the spot, and you’re wanting me to share that. I am so grateful to you both for paving the way for other Black woman scholars. I don’t do this work alone. Ubuntu, “I am because we are.” Thank you, so, so much gratitude.

I know that we have only just a little bit of time left together, I have one more question to pull the conversation together. For those that are still on the call, don’t forget to fill out the evaluation form. As we come into our last question, I love quotes, so I’ll pull in one of the quotes from your book. You write, “Black women’s history, in its truest sense, serves a historical roadmap of the failures of mainstream approaches to democracy, and an incisive tutorial on how to correct it.” So, what can we learn from the historical roadmap to both understand and teach the ongoing struggle for freedom?

Ramey Berry: That struggle has always been a part of Black women’s experience in the United States, and we understand and recognize it in various time periods, and the freedoms that we’re fighting for change. As we get more freedoms, we’re fighting for new ways to be respected in society. I think that that’s one of the goals when we’re looking at mainstream history books. But there’s no excuse that there’s not a Black woman in that time period, because we’ve identified a number of women that were activists and artists, entertainers and just everyday human beings, mothers, daughters, sisters, that lived in the United States and contributed to our history. So that’s my hope for this project.

Nicole Gross: For sure. I’m trying to keep it short, I know we’re running up against that time. I think they show the places where democracy has really failed in terms of being exclusionary. One thing, where we pay homage to these ideas — like liberty, the pursuit of happiness, and all the rest — but when it comes down to actually having freedom and true citizenship, there are all these spaces throughout history where it’s failed Black people, and Black women especially. So, I think their resistance helps to highlight those failures and, at the same time, all the ways that they have managed to change those structures to bring out more equitable treatment.

Not that the problems are solved. We know that they have endured and that these things happen in fits and starts. Racial progress, social justice, a lot of time starts with fits and starts. It’s not necessarily a linear process. But they’ve given us a really powerful blueprint in terms of thinking about activism, whether it’s collective grassroots organizing, whether it’s using the power of the press, and now what we have with social media, where they’re organizing and seeking political office as a way to make change. We have Black women who advocated for self-defense, and advocating that with respect to a Winchester rifle, thinking about Ida B. Wells. Before we have “by any means necessary,” Ida B. Wells was telling everybody, “Make sure you own a Winchester rifle and have it at a prized place above your family hearth.” We have examples of Black women going abroad to advocate for justice for Black people, so making our struggle global, also. We think about all the many tactics that Black women have accessed and mobilized, from liberating themselves to all of the other approaches that I just laid out. That’s why I say if you look at that history, you have a blueprint for how to resist and how to continue to press, and to keep moving forward.

Kaler-Jones: A blueprint to resist, a historical roadmap that paves the way forward all of us towards freedom, liberation, and communities and societies centered on love and justice and joy. We are nearing the end of our conversation and I could talk to you all forever, but I know that with time limits, we must prepare to close. I just want to quickly mention for everyone on the call, we have relevant lessons on the history of Black women at the Zinn Education Project, including the Voting Rights unit and the lesson on the long history of the demand for Reparations. I’ve used Resistance 101 as one of the lessons in the program that I just described with high school students and lifting up many of the stories that were in A Black Women’s History of the United States.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

Here are many of the resources recommended by the presenters and also by participants in the chat box.

Participant Reflections

Here are some of the responses by participants from the session evaluation.

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

Harriet Robinson Scott’s story just shows how textbooks perpetuate the injustice of her exclusion in the “Dred Scott case” by continuing to exclude in textbooks and classrooms.

The story of Black people does not begin at enslavement. People who came to America before slavery.

I realized how little I know about Black women’s history in this country!

Stories of Isabel De Olvera, seamstresses, queer and trans folx mentioned.

I learned about the power we have to reframe the story by changing the language. “Self liberators” vs. runaways or fugitives.

Black women developed their own organizations.

There were some early arrivals of Black women in Anglo-North America seeking freedom from slavery in the Spanish Empires.

I have been concerned about making it clear to my students the history of oppression in the USA and its continued relevance today, but not only focusing on the oppression — especially at the expense of the positives and joy in the Black historical experience. So, the idea that focusing on resistance and triumph is still covering the trauma and oppression while centering Black experience; that my white students will still learn about the oppression without having to only talk about the atrocities. That said, that there are ways of focusing on the white perpetrators — like showing a lynching photo with the victim removed and focusing on the white participants.

The resources we need are out there; We just need to make sure we bring them into our schools and communities.

The importance of seeing yourself in history.

The concept of “community history” and the idea of the continuum in Black women history.

About how important Black women’s STORIES are — it is stories that make history come alive.

UNBUNTU — I am because we are!!! “Black women have continued to fight at great cost”

The unknown Herstories coming to life, crucial contributions being returned to the historical record

Dr. Berry’s statement: “Black women were free before they were enslaved.”

Callie House (reparations efforts), Mary Colbert (nobody looked at her), Frances Thompson & Transcestry, Sankofa. Wow. So much amazing and powerful content to explore and pull into my classroom.

Black women’s history shows us a blueprint for how to resist. And there isn’t a time period in U.S. history that shouldn’t have a Black woman’s story.

I learned about the intellectually destructive ideologies that the master narrative of the Black struggle for freedom in the United States perpetuates. It erases Black women from the spotlight even though they were in every aspect of the fight for freedom.

So, so much! I just learned so many names and stories that I didn’t know before this session that my head is spinning.

Harriet Scott’s story — as a highlight of how often women, and women of color, are REMOVED from stories

There were SO many Black women I did not know about. What is standing out, in particular, is the story of the Tinkham Bill — fascinating!

Everyone is present in the history of Black women. The women highlighted in today’s session were each so multifaceted that I know that every student in my classroom can find relatable aspects to their own life. It is all so much deeper than the skin.

Black women have always been fighting, always been activists, always been leaders.

Every story was new to me. As I shared in my breakout group, I was educated in the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s. I am thrilled that at least now I am learning the true history of the US. Black history is so rich, and I am eternally grateful to ZinnEdProject for the classes and your work.

The importance of telling the stories of Black women holistically, so that the beautiful and joyful is included with the ugly and violent, the free with the enslaved, personal and community agency and engagement with degradation and captivity.

I am blown away by the depth and breadth of stories of Black women available and the diligence and tenacity of the historians who collect and pass these stories on. I really resonated with and was inspired by all of the stories that seek to expand the narrative before 1619, or to add richness to narratives around the women’s suffrage movement.

The queer women and the erasure of Mrs. Scott from the court case. Early court cases where Black women sued to protect themselves and to seek justice for vile offenses.

The story of the woman harassed and tormented to find out if she was “biologically a man” really stuck with me. I always am brought back to how interconnected and related women’s rights, trans rights, and Black civil rights are. It can never be over-emphasized how important their roles are even today.

Telling Black women’s history in the context of other Black women’s history, instead of as an exception within the otherwise white, male narratives that are treated as default

The most important thing I learned was to reframe Black people are free FIRST – begin with stories pre-enslavement and emphasize the un-natural state of captivity and the ways Black people resisted and self-liberated.

The power of Black women seamstresses. The ownership of their work and just the power of those stories really spoke to me. I also appreciated learning the phrase transhistory because it gave phrasing to something we’ve been trying to teach in class this year.

I think It would be how rich, complex and diverse the involvement of Black women has been from the foundations of our history to our present situations; yet these narratives have been marginalized (if not attempted erasure) or co-opted by structural and cultural hegemonic forces. So many discrete examples were highlighted to showcase the collective and intersecting struggles for justice and the right to exist.

Black women are always there in history, accomplishing wonderful, inspiring, important things. Easily available books – commonly read books – may or may not (probably) won’t include their stories. That’s why a book like this is so important.

I learned about the historical and iconic figures that helped expand the Black women’s movement and how we should not think about the pain but the power.

There were so many important stories, I felt overwhelmed. What I realize from this is that there are many ways to fit Black history in whatever I am trying to teach, and it doesn’t matter how small these moments may seem, what matters most is that we start somewhere.

That the stories are there, they can be found and written about. It takes diligence.

Early court cases where Black women sued to protect themselves and to seek justice for vile offenses.

Black women have been some of the primary ones to suffer when democracy and its promises haven’t been met but are also the first to continue to the struggle towards freedom in both large and small ways. I loved the term “motherhood activism” and seek to use it in my own work.

The intersectionality of race and gender is a very important space to highlight in the classroom.

What will you do with what you learned?

Pass on to my colleagues, as well as rework lesson plans/slideshows/activities for my U.S. history classes.

Incorporate more BLACK FEMALE STORIES in my curriculum; work to incorporate their voices through primary sources. Black women show where democracy has failed — how can Black women teach us how to strengthen democracy? Their resistance highlights those failures and how we must change those structures.

I’m looking forward to using Dr. Berry and Dr. Gross’s book in my U.S. History classes, as a way of centering Black women’s history and disrupting and expanding the dominant narrative of U.S. history.

Share with the social studies teachers at the school where I work; be refreshed by the intellectual, important, and joy-filled time with the people in the zoom tonight, share stories with students in my English classes; use the details in conversations I have with students in the hallways or during lunch duty when their misunderstandings of history and their questions arise

I teach early elementary and a big focus of mine is deconstructing the idea of social movements having one hero. I am SO EXCITED to learn more about these amazing women to pull into my lessons about people that have impacted history and supported social change throughout history

I’m looking forward to bringing some of the stories to life through theater and art next year.

I am teaching the newly adopted African American Studies course. As I am the first to teach it at my school, I am hoping to include as many voices as possible. Today’s session and this book is giving me a wealth of resources!

Expand the superhero stories to be more realistic and accessible to mere mortals. Use that more complete understanding to empower.

I will read the book! I will incorporate more essential stories of Black women into the biographies I present to teach American history.

Most immediately, I am currently planning a unit on art and activism and I’m excited to share the works of all of the Black women shared tonight.

I will use the book to supplement my anchor text of A Young Peoples History.

I am an English teacher. I teach a racial stereotype analysis project during unit 1 sparked by Chimamanda Adichie’s “The Danger of a Single Story.” I teach on the origins of race in the context of the land that is now the U.S. to scaffold how to analyze who is materially harmed by racial stereotypes, who benefits from racism, and how they benefit. I usually start in the early 1600s when some Black people occupied positions similar to indentured servitude in the colonies, then I teach how laws changed to make slavery hereditary/matrilineal and the aftermath of Bacon’s Rebellion caused white enslavers to tighten the laws and make “racial bribes” so poor whites wouldn’t unite in solidarity with Black people. (I use a Zinn Ed resource for this as well as Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow.) Now, however, I’ll back up more to emphasize Black freedom first, pre-1600, like the speakers talked about in the talk today. I’ll also speak more about how Black women resisted (such as with headwraps) and fought for bodily integrity and freedom, since I tend to emphasize the mass rape part of Black women’s enslavement without saying much else about Black women specifically. I’ve also ordered a copy of the book to inform this work.

I will continue to develop and share my knowledge and resources in black history, social justice, and anti-racist education, with those around me. I can in to my lessons. As an example when teaching American symbols to my 1st graders I can bring up Grace Wisher.

It will be folded into the Women’s History Month unit we are working on now in freshman English and in next month’s poetry unit. I have the reins. . . so it is going to be done!

Read the book, report out to my colleagues about the book and class, find ways to weave in these stories to my curriculum

I will share this with my kindergarten grade level team and the students and families in my classroom.

As a museum educator, I want to pull more stories of Black women to the forefront of my work with students and educators. I also want to be more intentional about where the stories of LGBTQIA+ females is illuminated in my work.

What did you think of the format?

I thought the format was perfect. I only wish we had more time because it went by so quickly. The mid-breakout sessions were nice. I was surprised the groups could be so small given how many people were on. It was fantastic! We could actually have a conversation

All was excellent. I’m so grateful for breakout rooms — not just the opportunity to chat but also that you model the need for learners to process material in order to actually learn.

It was good to talk with people. It reminds me that there are lots of social justice people out there and it is important to connect with and draw from each other’s optimism, knowledge, strength and sense of purpose. It could be helpful to know the questions a little more ahead of time but I may feel that way because it’s late in Maine! Perfect amount of time for breakout room.

Everything worked! The ability to reflect on the workshop was indeed refreshing and enlightening! I absolutely love using the chat to share resources! I saved every link and my goal is to share each resource with my teachers! Thank you!!

I have come to a bunch of Zinn sessions. I really appreciated having two (really three) speakers tonight — the exchanges and way Dr. Gross and Dr. Berry played off each other’s comments was superb. And educational!

This was my first ZinnEd program. I really enjoyed all of it.

I appreciated the exchange between Dr. Berry and Dr. Gross. Their conversation was so full.

Liked the suggestion to put questions in the Chat in all caps, made it easier to see and find them.

I enjoyed the opportunity to process the topic in small groups.

Cierra’s questions + the quotes she selected from the book were awesome! I loved the way this session had questions from very specific details in the book. I also really appreciated the way the presenters shared their story of writing the book + their strategies for staying healthy for the long struggle we continue.

This was the first Zoom breakout room that I’ve done in such a large setting that actually worked, and it broke up the format nicely.

The warning of the breakout room time being too short proved true. However, this is not a criticism or recommendation to change the time as it served to both: make me want to hang out with a group like this mine more and helped me appreciate the gravity of what we were just taught.

I thought the format was really wonderful. The ability to go into breakout rooms really allows for closer conversation with a few people who have had the same experience. The time was a good amount for the number of people.

Additional Comments

Even more important than the book and the stories in it, to me, is the story of how the book was written and the example in the class itself of collaborative scholarship by Black women to tell our own stories in our own ways.

Thanks for continuing to do these sessions. Not just informative but also inspirational.

Thank you, this was a wonderful opportunity to connect with scholars, peers, and a community leading work for social justice and equal representation in history.

Thank you. Amazing from the content to the work of two fantastic scholars

I could spend a lot more time listening to these women. Thank you for the opportunity to learn and grow. Peace!

It was a great session. I have invited two of my teachers to join this series.

Thank you for this INCREDIBLE scholarship. It is important, tragic, and inspiring.

Thank you for this wonderful lesson. This will not be my last class.

Trans-cestry, Black and Latinx history. . . This is so important to explore, thank you.

I would love to attend a class by Cierra Kaler-Jones about her use of art.

Thank you so much! This was my first Zinn class, but if they are all like this, I will be in every one of them!

I loved the way that Dr. Berry and Dr. Gross brought transparency and humanity in telling the stories of their collaboration and writing process.

I have a persistent question about authenticity in telling others’ stories, as a “white” woman, and how do I move toward that the best I can. I can see that vulnerability is a big part of how that can happen, and that it will keep evolving as I do.

I am both inspired and saddened by this presentation. How differently would our country be if we had learned this part of our history growing up. . .that the stories we heard today were just as common as the midnight ride of Paul Revere? How differently would our society treat Black women? How differently would society treat all women? How differently would our babies see themselves? I am inspired by the work of Dr. Berry and Dr. Gross, and I thank you.

Presenters

Daina Ramey Berry is an award-winning history professor and Michael Douglas Dean of Humanities and Fine Arts at the University of California, Santa Barbara. As “a scholar of the enslaved” and a specialist on gender and slavery as well as Black women’s history in the United States, she is the associate editor for The Journal of African American History.

Kali Nicole Gross is a professor of African American Studies at Emory University and the Martin Luther King Jr. Professor of History at Rutgers University. Her primary historical research explores Black women’s experiences in the U.S. criminal justice system.

Cierra Kaler-Jones is the Education Anew Fellow at Teaching for Change through the Communities for Just Schools Fund. As a Ph.D. student, her work examines how Black girls use arts-based practices (such as movement and music) as forms of expression, resistance, and identity development.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn