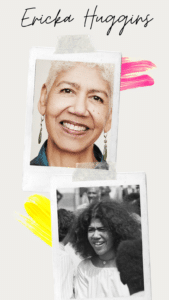

On April 14, historian Mary Phillips joined Rethinking Schools executive director Cierra Kaler-Jones and editor Jesse Hagopian to discuss Phillips’ book, Black Panther Woman: The Political and Spiritual Life of Ericka Huggins. This is the first biography of Ericka Huggins, a queer Black woman who brought spiritual self-care practices to the Black Panther Party.

Watch our 60 previous Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online classes and register for upcoming classes here.

In the excerpt below, Phillips discusses the internal work and collective healing that Ericka Huggins engaged in with other Black Panther women while incarcerated, and how this critical “rhythm of care” was both a spiritual and a political practice.

The most important thing I learned from Erika Huggins’ story is the power of her tenacity and her commitment to showing up as her best self — not just for her child, but for all students. Her ability to transform pain into purpose, rooted in the selflessness that so many Black women carry, is deeply empowering. I was especially moved by her emphasis on wellness, self-care, and self-love — things I know I need to prioritize more in my own life.

This class was such a beautiful contradiction of the lies, smears, and criminalization of the Black Panthers that have been so central to education and media characterizations of their work.

That the women of the Black Panther Party were the real changemakers!

The whole session was amazing. Something that stood out to me was the theme of care and the many powerful examples of collective care in Ericka Huggins’ life and practice. These concrete examples provide models of what people can build together, and of critical connections between individual healing and collective healing.

I learned how a Black feminist lens in the oral history of Ericka Huggins can amplify the importance of her work in the movement along with other women.

I think the relationship between collective care and self-care in activism and education is the most important idea I’m sitting with this evening and taking with me into my work.

I learned the importance of taking the time to critically think and to look beyond the surface. The Black Panther Party, like many other social justice groups, are too often downgraded or disparaged. By taking the time to learn more about such movements I am better able to challenge negative misconceptions.

That the Oakland Community School encouraged culturally responsive teaching before educators realized there was a need for it. I was inspired by Ericka’s advocacy while she was in jail, as she used letters as a political tool.

It’s hard to choose one takeaway! I think the power of collective resistance stands out given our current political climate, along with the agency we each have to make a difference within our own classrooms and spaces.

Event Recording

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: Thank you for joining us for another session of the Teach the Black Freedom Struggle classes. My name is Jesse Hagopian. I work with the Zinn Education Project and I’m an editor with Rethinking Schools. I’m excited to be joined this evening by my colleague, my comrade, Cierra Kaler-Jones, executive director of Rethinking Schools. Glad you’re with us this evening. Today’s class is hosted by the Zinn Education Project, which is coordinated by Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change. We offer free downloadable people’s history lessons that many of you have used for middle and high school classrooms from the Zinn Education Project website, including many on the theme of today’s session, the Black Panther Party. We have an awesome lesson about where students get to create their own 10-Point Program based on the Black Panther Party’s model. We have another lesson that me and my colleague Adam Sanchez wrote together on what you didn’t learn about the Black Panther Party in school, but should have. So check those out.

Now I am extremely happy to welcome back historian Mary Phillips. She is associate professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and she is the author of the book that we will be discussing today, Black Panther Woman: The Political and Spiritual Life of Ericka Huggins. Mary, welcome back, and thanks so much for joining us.

Mary Phillips: Thank you for having me. I’m so excited to be back.

Hagopian: Right on. I’m so glad that you wrote this book. I’m so glad you were willing to come discuss these ideas so all these educators can teach a more complete understanding of Ericka’s life, of the Black Panther Party, and really of the Black Freedom Struggle. So much of those stories are all bound up in this work.

I wanted to start by asking you about reclaiming the Panthers’ legacy, because the Black Panther Party, I believe, is one of the most distorted parts of the way the Black Freedom Struggle is taught in school. We looked at textbooks and how they covered the Black Freedom Struggle and the Black Panther Party specifically, and we found some of the major textbooks don’t even mention the Black Panther Party. One of the largest socialist groups in U.S. history, one of the largest Black revolutionary groups in history, is just completely absent. And then those that do often reduce their work to one or two sentences, and usually completely distort their ideology and their contributions.

There’s this textbook called History Alive!: The United States Through Modern Times, and they wrote this. I had to share this with you. In this textbook, it says, “Black Power groups formed that embraced militant strategies and the use of violence. Organizations such as the Black Panthers rejected all things white and talked about building a separate Black nation.” This isn’t just a distortion, it’s just an outright lie. I mean, that’s just not what the Panthers stood for, right? They were not trying to build a separate Black nation. So, for those who may be less familiar, can you start by giving us a brief overview of the Black Panther Party — who they were, what they believed, and what kind of work they were doing in communities across the country?

Phillips: Yes. So, the Black Panther Party was founded in Oakland, California in 1966, and they function as a grassroots political coalition building organization. You know what I say is Black Panther activism is a practice of care and belonging to empower communities. The Panthers believed in liberation for Black and oppressed communities. In theory and in practice, their mission was fundamentally concerned with communal care and restorative justice. They were not anti-white. In fact, they formed coalitions with white progressive groups and feminist organizations, among many other coalitions that they formed. They met the changing needs of Black and poor communities nationwide through social service initiatives.

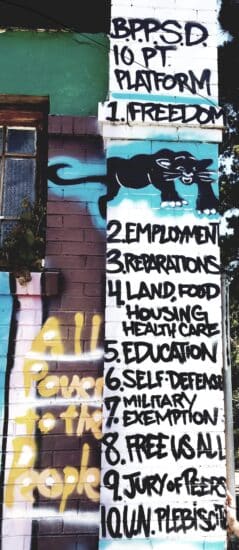

Mural depicting the BPP 10-Point Program, as seen on the side of Marcus Books in Oakland, California. Source: Josh Davidson

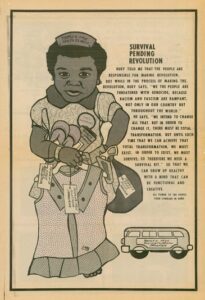

Much of this we see outlined in the Panthers 10-Point Platform and Program. Their community programs sought to remedy the effects of racism and capitalism on Black communities as they related to issues such as unemployment, housing discrimination, inadequate education, and legal and state violence. The heart of their work, the bread and butter of their work, are more than a dozen of their community programs, which included the breakfast program, the Panthers health clinic, the free bussing to prison programs, their free shoe program, free pest control, and the free food program. One of my favorites is the free ambulance program, the Intercommunal News Service, free plumbing and maintenance. And then liberation schools, including the Oakland Community School, to name a few.

Hagopian: Yes, thank you for that important overview that often gets purposefully excluded from our textbooks.

Cierra Kaler-Jones: Yes, absolutely, the coalition building, the power of taking care of ourselves and our community when we know the government won’t, that reclaiming. I love how you are lifting that up through this book. Another thing that Jesse and I were really interested in was your process in writing the book. In Black Panther Woman you write, “I came to this experience as the interviewer, and yet I quickly learned that I was the interviewee.” You reflect that she was not a research subject but a guide, and in relationship to Ericka Huggins, you describe a profound inversion of the typical sort of researcher subject relationship in your first conversation with Ericka Huggins. So, how did Ericka’s role as a revolutionary teacher complicate or enhance your role as the historian, and how did that early exchange really reshape your understanding of what it means to do oral history work through a Black feminist lens?

Phillips: The inversion I described in the opening of the book really pushes back against the traditional approach that I was expecting as a historian at the time. That first interview that I did with Ericka, in which that conversation happened, I was in graduate school. I was in training, and it immediately forced me to shift and to begin to think differently about my approach to writing on someone living, writing on someone who cared about what I was writing and who was very much invested in the work. It was a process because of our sustained conversation over the passing of years that constantly pushed me to go back to the Black feminist thinkers that I was studying, to turn to other Black feminist historians to dialog about this journey, who was doing this work. In so many ways it enhanced my role as a historian. It taught me so much about building community with the people you are interviewing and being open, really open, to hearing their stories and listening to their inner world.

That early exchange helped me think about the power of feelings and emotions. I remember in that first conversation, Ericka said to me, “I want you to understand how it feels to be written about when we are still alive.” And those words still stick with me today. It really helped me think about the crucial role of affect and telling stories, and the many layers that come through that. It completely reshaped my approach to oral history as a Black feminist; Black feminist thought deeply informs my work. The idea of the personal and political has so much power and meaning in Black women’s lives. Bringing that out in the writing, in the storytelling, is so critically important for me as a historian, as a storyteller.

Feminist thinkers informed so much of my work. For example, I talk about this in a book, the Combahee River Collective’s Black feminist statement reiterates the fact that political practice begins with feeling. They insisted on personal experiences that are crucially bound to radical community politics, and [they] asserted that Black feminist politics are intersectional and combat structural inequalities affecting the individual and collective lives of Black women. And Ericka’s historical intervention stands at the crossroads of racism and sexism and continues to build on the analysis of the Combahee [River Collective]. So, it was really life-changing for me as a historian to go through that experience and that process in writing a biography on a person that’s still with us.

Hagopian: We can feel that that power comes through in your words, and that intersectional framework, the framework of the Combahee River Collective, is just so present. It’s really inspiring to see those politics continue to be translated for new generations. This is a wonderful contribution to that.

I want to dive into some of the narrative of this book now. As a young teenager, Ericka asserts her independence by insisting on attending the March on Washington despite her mother’s fears. I love this part of the book, and I wanted to get into it more, because in a moment that I think many parents can relate to, she flips her mother’s own words, her own teachings, back on her. Ericka says, “But Mama, you don’t want me to go. You’re afraid for me. But you taught me to love Black people.” She said, “What it means to love Black people is I’ve got to go.” So, what does this movement reveal about Ericka’s early understanding of political commitments, and how does her decision to attend the March on Washington despite the risks shape her spiritual and her political development going forward?

Phillips: Ericka was resolute that she was attending the March on Washington, and this was a turning point where she made a commitment. She made a vow that she will serve her community for the rest of her life. And she stood by that, and she met that. This desire for her to go doesn’t come out of nowhere. This moment built itself through storytelling, the power of storytelling that I talk about in the book. She listened to stories from her mother, talked to her and her siblings about overt racism and the cruelty her family experienced during the Jim Crow South, and also dealing with the KKK, as well. And many lessons came through this power of storytelling. These lessons culminated in Ericka’s first, but not certainly the last, confrontation with the police. It was her parents’ lessons about racism, family bonds, and faith that gave her and her sister Kyra the courage to confront the police.

As teenagers, they were around the same age as Emmett Till, and very aware about the violence that Emmett Till went through. They were watching television. They knew about the ongoing Black protests. They were deeply engaged politically. They were very aware about the ongoing Black protests about the movement to desegregate public spaces. In that neighborhood, they often saw the police harassing Black people for no reason. They knew the history of the Black struggle, and their loving hearts gave them the courage to confront the police. But it was not until later that they realized that these actions could have actually gotten them killed.

Ericka was very political as a young child, very engaged, very aware, asking questions. We also see this in the church, which I talk about in the book, and the questions that she asked and trying to understand, and even the pushback that she got at Sunday school, asking critical questions about the lessons that she was being taught. She was always thinking critically. She was always questioning. She was always politically aware, even as a young child. We see this development in the book, in various different contexts that I trace, that leads up to this moment of attending the March on Washington. Going by herself, traveling as a young girl, her parents were very concerned about her safety, but she went, took in that moment, and then came home. But, it was a commitment that she said, “I want to do this work as well.” And there’s something to say about that.

Kaler-Jones: I love this story, and I love how you lift up the power of storytelling, especially during these times where there are these bans on teaching the truth about history. Because that’s exactly what happens, right? When we learn these lived experiences, when we learn about these stories, these truthful histories, we start to organize, we start to mobilize, we start to resist. And Ericka Huggins’ life definitely is a demonstration of the power of what it means to teach the truth about history.

Let’s talk a little bit about answering the call and joining the Black Panther Party. Ericka’s decision to join the Black Panther Party is really sparked by our powerful, emotional response to a photo of Huey P. Newton, wounded and strapped to a hospital gurney, which was featured in Ramparts magazine. She says, “I felt called,” echoing the deep conviction that led her to the March on Washington, as you discussed years earlier. She and John [Huggins] drop out of college, they drive to Los Angeles, and soon begin working full time with the Party. How does the sense of being called really shape Ericka’s commitment to the Black Panther Party, and in what ways do her early tasks like selling newspapers, cleaning the office, attending political education classes, really reflect both the everyday work and also the deeper struggles that defined Panther life?

Phillips: Let me say a couple of things. Ericka is very intuitive, knows how to listen to her body fully, and she knew this at a very young age. I opened the book about her with a story of her looking in the mirror and understanding that there is something deeper there. There’s something bigger inside me that I’m not able to see, and trying to figure that out. She follows [her] gut, that voice inside you that never steers you wrong, that keeps you focused. Some of us may follow it, some of us may not follow it. It was these moments where she followed that intuitive spirit that was inside of her, and that became critical, and you see this unleashing itself in different political moments throughout her journey.

But what it showcases also, when we talk about selling newspapers, when we’re talking about cleaning the office and all of these early tasks that she was doing when she joined the Black Panther Party, which really everybody was doing — attending political education classes, selling Black Panther newspapers — it showcases that everyday work was just as political and important and actually helps the deeper political struggle of what it meant to be a Panther.

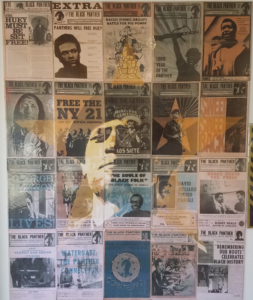

A collage of Black Panther newspapers, as seen at It’s All Good Bakery, the original Panther office in Oakland, California. Source: Josh Davidson

All of these tasks were critically important in the operation of the organization. All of this work is what it meant to be a Panther. And it all mattered. Being a Panther was something that you were involved in around the clock. It was a full commitment. You live together, you bonded, you work through issues together, you talk through things together. This was truly your comrade in struggle. So we were able to look at even these everyday tasks in a political way, because they hold a powerful political meaning in the work that we’re doing.

Hagopian: Thanks for giving us a window into what it was like to be part of the Party and the credible, electric work that they were engaged in. One of the things that, as a teacher, I’ve been most inspired by is their work in education, and that’s why Ericka Huggins has always been one of my favorites of the Black Panthers. Her work as a revolutionary educator is unmatched in this country’s history, I think.

You write about how Ericka Huggins became the director of the Oakland Community School, the most enduring and expansive community program of the Black Panther Party. Under her leadership, the school embraced culturally relevant, holistic, non-hierarchical, antiracist, anti-imperialist education, offering everything from meditation to martial arts to writing to science to dialectical materialism. Such incredible curriculum. And the Oakland Community School wasn’t just a school. It was a space where students, many from working class Black families, could be seen, they could be supported, and they could be loved. Those politics of Black feminism, I think, really came into play with the way the school was developed. Can you talk more about the radical educational vision of the Oakland Community School and what Ericka specifically brought to that work, and how the school reflected the Panthers’ broader political commitments And, I think importantly for this audience this evening, what lessons can today’s educators, organizers, and parents take from this bold experiment in revolutionary education?

Phillips: I think what made the school so special, so unique, was that it was non-traditional in a lot of ways. Even the way that the students were evaluated, or in the ratio of the classroom, there was a low student-to-teacher ratio, and students received an education tailored to their learning needs and styles. They had a very distinct grading system that did not include placement in traditional base classes. They did not use letter grades as a form of evaluation. Instead, teachers assigned students to a level based on their ages and actually hand wrote evaluations on their students. They met the students where they were. They had this model, each one teach one, and it was a very collaborative approach. You had these students that were very much involved in each other’s learning, and they were learning from each other. The pedagogy was holistic. It was culturally engaged. They adapted a whole body of education where students’ abilities were attended to all of their abilities, their abstract needs, their social emotional needs, their cognitive needs, and their linguistic needs. If a student wanted to act, they figured out a way to help them pursue that. All of their desires were met by the lessons.

What is truly riveting about the school is that they applied this curriculum that places care and empathy at the center. When we talk about their experiment, they were bold. They thought outside the box. They were generative. They had this cultural understanding. Even the teachers would meet and talk through their own biases, to really work through any concerns in the classroom or any issues that they may have had, as well. So, it wasn’t this approach where I know it all and I’m teaching you. I can’t emphasize the collaborative nature of the school enough.

One thing that I love about the school is the idea of dialectical materialism, the idea that we need to see the infinite possibilities of something because it has so much use and understanding for us as we live our lives. What can we do with a little bit of resources? What can we turn that into? This might look like a bottle of water, but you can do so many things with that. The school very much taught you how to play, and taught you how to really tap into your creative understandings, as well. When I think about the lessons, I’m thinking about all the manifold ways that we can learn our students’ needs and work with whatever you have access to to make things that may seem impossible possible.

Ericka brought all of those spiritual wellness practices that she taught herself in prison to the school meditation, like yoga. She’s having these young elementary school students do yoga to help them focus, to help them center their energies. She’s having them engage in meditation. I remember Ericka shared with me, “When I see a student that went to the Oakland Community School, even today, I know right away that they went to the school because of the calmness and the energy that they evoke that really speaks to the work of meditation, yoga, and these spiritual practices.” I’m paraphrasing her words, but I think that’s pretty powerful.

Hagopian: No doubt. I mean, it’s incredible to see this model of education that they created before widespread Freire applications and widespread play-based curriculum. They were so ahead of the curve in terms of understanding how kids learn, what they need to learn, and the kind of supportive, collaborative environments that are needed to produce those conditions.

Kaler-Jones: Thank you for helping to tell that story. It is so beautiful and so powerful what you said, and seeing the possible in what may be seemingly impossible, and how we can create that in classrooms and communities.

So, shifting a little bit to really think about Black feminism in the Panthers, Ericka recalls that the LA chapter where she first joined did not divide the work of the Party along gender lines. You write, “[Alprentice] Bunchy [Carter] was a grassroots intellectual who taught political education emphasizing a pedagogy of community love.” Ericka, who was highly attuned to care politics, and was particularly moved by his teaching, which emphasized that care work did not reproduce gender norms within the organization. John and Bunchy were fearless Black Panther Party leaders who considered women equal partners in the struggle.

But when she later visited the Oakland chapter, she had a jarring experience. She was told that the men would eat first, and only afterwards could the women who had cooked the meal sit down to eat. So, what do her reflections on Bunchy Carter and her contrasting experiences in Oakland reveal about internal struggles within the Party around gender, and how did Ericka and the women who formed the majority of the Black Panther Party by the late 60s, early 70s, really developed this international, intersectional praxis that linked Black liberation with women’s liberation?

Phillips: Yes. It reveals that there were internal conversations about gender that were happening all the time. This is documented in many ways, in the Black Panther Party newspaper you literally see an accounting of the history, not just of the organization, but of these conversations that we’re talking about based on their lived experiences as Black women in this world who were organizing politically. They were very aware of the intersections of race, class, and gender within the organization, and how the state perceived them, treated them. The inhumanity of the state spared no age or gender.

Women in the Black Panther Party built coalitions with the Black feminist movement, and were very much deep in conversations at that time with Black feminist activists that engaged intersectionality and that challenged sexism. And women defined these ideas on their own terms. That’s really important, and part of why I included that story is I wanted readers to understand that when we think about gender politics, they don’t look the same. It was very complicated and complex. It had a lot to do with what year we’re talking about, what chapter, what location, right? It’s very complicated. Oftentimes, people like to do an overview, and say it all looked the same, and gender politics were this way or that way. But it wasn’t like that at all. There was always an internal conversation happening. Particularly when we talk about the women’s liberation movement, the Panthers were quite engaged with that conversation, as well. And work with Black feminists, too. So that’s important to know.

Hagopian: No doubt. I think a lot of people don’t realize that the Panthers were majority Black women; certainly by the late 60s, early 70s, that like 60 percent or more were Black women. Most people’s idea is the man with the shotgun and the beret. They don’t understand that women were leading this organization, even came to run the whole organization at one point. So, I think that really helps us better understand the direction that the Party took and the way that the politics developed. So, thank you for laying that out.

On January 17, 1969, Ericka Huggins’ husband and fellow Panther John Huggins, along with the leader of the LA chapter, Bunchy Carter, were both assassinated by representatives of the group US [United Slaves], but also COINTELPRO, which instigated that assassination. In the aftermath, the police arrested Ericka on the outlandish charge of conspiracy to retaliate. It was during this time that Angela Davis, one of Ericka’s friends, described her as “the strongest Black woman in America.” So, I was hoping you could talk about where her strength came from, and what it looked like in practice? How did her spirituality and politics, especially her emphasis on care, meditation, and spiritual wellness, contribute to that strength that she had in the face of this profound grief, isolation, and state violence?

Phillips: Ericka was very intentional in her work. She was very intentional about healing from the inside out, and she knew she needed to do this to survive prison, to survive whole and intact. That was critically important. Part of her strength came from her baby, Mai. She was separated from her child, and John Huggins’ mother would bring Mai to [Prison Niantic State Farm for Women], where Ericka was incarcerated, once a week on Saturdays for only an hour. She wanted to be well, she wanted to be healthy, she wanted to be fully present for her daughter, Mai. She did not want her baby daughter to experience her sad, broken, and wilted, and that was part of her drive and her motivation.

She went to one of the lawyers that was on her legal team, Charles Garry, who was a well-known yogi. He would do headstands before he went into the courtroom. She said, “I need a book that can really teach me yoga and meditation.” Gerry gave her one and she taught herself yoga and meditation. She did that when she was able; during her incarceration, she was not allotted any more than 30 minutes, so she would squeeze in that time when she could. She maintained this when she was segregated, when she was a political prisoner, and when she was isolated. She worked on herself, and she worked on healing from within.

She also engaged in what I call in the book care, this rhythmic care, a rhythm of care that she practiced with the other Panther women she was incarcerated with to care for one another. One of the women had arthritis and the coldness of the floor worsened her arthritis. It was debilitating and it was painful. So the Panther women came together, lifted her up, and helped her get out of bed as needed. Some of the other women were pregnant during that time, so the Panther women would give them the better parts of their food, when it was edible. Much of the time it wasn’t edible; the food didn’t even look like it was supposed to look, and the normal colors that food is supposed to have. Oftentimes, the food was expired. Food is used as a form of punishment in prison.

But they cared for one another as much as they could. Ericka had worked on herself so that when she was placed in general population she knew that she needed to turn to community, and she had worked on herself so much then. Now, she had more energy to build community with those in general population. I know we’ll get to some of the political organizing work that she did, but when she got into the general population, I also want to point out her resistance. While she is involved in these care practices, which is its own kind of resistance, she’s also using her body as a form of resistance — planning food strikes, fighting back against physical assaults, pushing back as much as she could on body searches that they were doing, refusing medicine (and maintaining documentation of medicines that they were trying to distribute to her and other panting Panther women), challenging authority, consistently interrogating prison officials, questioning them, and requesting written documentation of the rules they attempted to enforce. She’s pushing back against the various forms of violence that she and other Panther women are experiencing, and this continues when she gets to general population.

Hagopian: Yeah, we want to talk more about her experiences in prison, how her organizing continued uninterrupted behind bars, and how she survived that period. There’s so much to dig into.

[breakout rooms]

Kaler-Jones: Alright, an exciting time to get back to the conversation, with more stories and more things to learn. As we jump back into the question, Mary, you also write about the ways that Ericka Huggins cultivated spiritual wellness, care, and resistance during her trial. Despite facing the threat of life imprisonment or the death penalty, Ericka built intimate, humanizing relationships with correctional officer O’Connor, who treated her with dignity, and with reporter Jan Von Flatern, with whom she exchanged emotionally rich and politically meaningful letters. So, can you tell us about the outcome of her trial and how Ericka’s small acts of care and connection — whether that be smiling, letter writing, or the organizing that she did — help reframe our understanding of what resistance can look like, especially in carceral settings? What does her story teach us about the connection between spiritual wellness and building political power?

Phillips: The political work that Ericka did while she was on trial is really an extension of the work that she did when she was not on trial. Back in prison, she is serving the needs of the women that she was incarcerated with. She started the Sister Love Collective with another young prisoner, teenager Millie Rivera, and it was about meeting the spiritual, physical, and therapeutic needs of other prisoners. They did this in a multitude of ways, to really be in touch with their humanity, to reassert their femininity.

But this was also done when Ericka was on trial, through letters. These letters were important because this was how she was able to communicate with the outside world. If there was a prisoner who was being neglected medically, who wasn’t getting the proper medical care that she needed, or was pregnant or needed prenatal clothes, Ericka would write letters to get her the care that she needed. So, these letters were critically important. You see a whole world in how Ericka used letters as a political tool to help fulfill the needs of these women that were being denied their basic human rights during their incarceration. It’s important when we think about this, because with her trial in particular there was a mistrial, and she was able to walk out of prison. She got her daughter and she went right back to work in the Black Panther Party, engaging in that particular political work of what it meant to be a Panther.

But Ericka teaches us that a little kindness goes a long way. When I talk about these acts of smiling, these moments where she smiled, these moments where she was writing letters, or she was organizing with others, she was really taking that work that we often saw on the streets, in the communities, and extending that within the prison settings. Oftentimes, we don’t hear about this and we don’t know about this. We don’t know what Black Panther Party organizing looked like among women within the confines of the prison. So you get to see a window of what this looked like.. It’s important because we have to heal from within and she teaches us that spiritual wellness and political power have meaning, and you can do more political work when you do the work of healing from all of the various forms of trauma that we have.

Hagopian: I love that, and I want to get more into her ideas around spirituality and political resistance that I think you beautifully illustrate in this book. You write, “She did not always get it right, but she modeled grace towards herself and others, embodying the essence of being beautifully human. Unapologetically embracing her Blackness, Ericka stands as an exemplar of spirituality as a form of political resistance.” So, in what ways does Ericka Huggins’ life and her practice of intertwining justice, wellness, and care challenge us to expand our own understanding of what political resistance can look like? I was telling you before this session that so much of the political organizing I’ve done in my life has not talked about care for each other, spiritual well being to our own detriment, so how might her legacy push us to redefine the goals of movements for liberation, especially in terms of who and what we choose to center?

Phillips: I think about what it means to think intentionally and how we interact with each other through the lens of care, through the lens of understanding that reframes everything, and how we are able to interact with one another, how we’re able to understand one another. The essence of what the work teaches us is that oftentimes we hear that political practice and spiritual practice are two different things. They don’t go hand in hand, right? They’re opposite in some way. And Ericka teaches us that they are always interlinked, or they should be interlinked. We are up against a system that is trying to destroy our humanity, so part of protecting ourselves is doing that internal work, really being in touch with our inner selves, really finding that strength from within when you are in your darkest, deepest place. Ericka was incarcerated and she didn’t think she would ever get out of prison, so she had to be in touch with that inner strength that really we all have. So, how do we intentionally work to be in touch with that in various moments, particularly in this political climate, and then doing that work as a way to be in touch with our political selves as well?

Kaler-Jones: That’s so beautiful and so necessary for us to think about and hold deeply in our own hearts, as educators, as organizers, as activists, and all that we can learn from Ericka Huggins and her teachings — as you call her, a revolutionary teacher. You also write that Ericka Huggins leans most toward the term queer, not necessarily as a fixed sexual identity, but as a political orientation. So, how does Ericka’s queer, Black, feminist practice embodied in spaces, like you talked about the Sister Love Collective, and expressed through her poetry, her relationships, and reimagining of liberation, how does it expand our understanding of what freedom can look like?

Phillips: Being unapologetic in how we want to live our life. When Ericka was engaged in political practice and spiritual practice, everyone in the Black Panther Party did not always understand what she was doing, what she was engaged in. But she took hold, she stood fast to that. The Panthers thought they were going to die; they felt like they were living in a war. So having those moments where you are living free, living in a way where you are thinking about the future in the present and making that a reality, is very radical. This becomes critical. She teaches us to live boldly, to live unapologetically in a lot of ways, to follow our inner sense of self, and to always see humanity in this complete fullness.

Hagopian: I love that. Mary Phillips, thank you so much for your time and insights in writing this book and in sharing it with us this evening. I wish we had more time, because there’s so many more things I want to go through. I highly recommend everyone get this book, read it, use it in the classroom, use it in organizing spaces, start study groups around it, because it is such an important guide to how we’re going to organize the next great uprising, the next phase of the struggle. It’s not just an important work of history. So thank you so much.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect, please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

Here are many of the lessons, books, and other resources recommended by the presenters and participants:

Lessons and Curriculum

|

|

What We Don’t Learn About the Black Panther Party — but Should by Jesse Hagopian and Adam Sanchez ‘What We Want, What We Believe’: Teaching with the Black Panthers’ 10-Point Program by Wayne Au Teaching Palestine-Israel from the Perspective of Civil Rights and Black Power Activists by Hannah Gann, Nick Palazzolo, Keziah Ridgeway, and Adam Sanchez COINTELPRO: Teaching the FBI’s War on the Black Freedom Movement by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca Framing Black Power Through the Life of Rosa Parks by Tiffany Mitchell Patterson and Jessica Rucker (this lesson features a photo of Ericka Huggins and Rosa Parks at the Oakland Community School) |

Books

Articles

|

“The Power of the First-Person Narrative: Ericka Huggins and the Black Panther Party” by Mary Frances Phillips (Women’s Studies Quarterly) “How Ericka Huggins and the Black Panther Party Attempted to Liberate Black Women in America” by Mary Frances Phillips (Literary Hub) “Radical Commitments: The Revolutionary Vow of Ericka Huggins” by Jaimee A. Swift (Black Women Radicals) |

Videos and Recordings

Women in the Black Panther Party, Mary Phillips and Robyn Spencer (from a previous Teach the Black Freedom Struggle class in 2020)

Black Panther Party Archival Collections

|

Black Panther Party newspaper archive, contains hundreds of Black Panther newspapers created and distributed by the Party between 1967 and 1976. Black Panther Party Museum in Oakland, maintains the largest archival collection on the Black Panther Party worldwide. The Freedom Archives, contains over 12,000 hours of audio and video recordings which date from the late-1960s to the mid-1990s and chronicle the progressive history, including numerous source material on the Black Panther Party. |

This Day In History

The dates below come from our This Day in People’s History collection, which contains hundreds of entries all searchable by date, state, theme, and keywords.

|

Aug. 28, 1963: March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Oct. 15, 1966: The Black Panther Party Founded April 6, 1968: Bobby Hutton Killed by Oakland Police Dec. 4, 1969: Black Panther Party Members Assassinated |

Participant Reflections

With more than 230 attendees, the conversation and chat were lively, engaging, and full of history, teaching ideas, and more. Polls showed participants included 39 percent K–12 teachers, 25 percent teacher educators, 5 percent historians, and more.

Here are more comments that participants shared in their end-of-session evaluation:

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

Everything I ever learned in school about the Black Panthers was heavily focused on violence and that Panthers wanted to establish a separate Black state. Always a heavy focus on the images of the gun-carrying, beret-wearing members of the Party and the conflicts they were involved in. This book and the information given tonight really focuses more on the heart of the Party and the role that education, community, and collaboration played in the Party.

Everyday work is political, especially as a teacher.

Black Panther lessons are not past history but living history. And the Black Panthers were mostly women!

How important women are to all movements of progress. We need to hear about them more!

What really stood out to me was the use of wellness and spirituality as an act of self preservation and resistance. I also like the emphasis on community building.

I came into the evening not knowing very much about the Black Panthers. I learned how they played an important part of their communities, providing food, shelter, and health support. I also learned how Ericka used mindfulness and yoga to take care of herself while she was in prison.

About Ericka’s ideologies — how to be intentional about healing from the inside out; about creating a “rhythm of care” and taking care of those around you to the best of everyone’s abilities which then gives you “more energy to build community.”

One of the important pieces I come away with is about the lens of care and understanding which is definitely missing in the United States at this time.

What will you do with what you learned?

I plan on diving into the book and using the Zinn Ed Project’s Black Panther Party mixer.

I will highlight the intersectional nature of the Black Panther Party and the role of women as leaders.

What I learned from Ericka Huggins’ story will push me to prioritize emotional wellness and mindfulness in any learning space I help shape.

For me, it was learning more about the Oakland Community School, as it directly connected to some work I am doing with educators to think about models of liberation and healing teaching pedagogy.

I’m definitely going to use this knowledge to debunk myths about the Black Panther Party and also share information about pedagogical practices with my colleagues.

I want to find ways to incorporate empathy and care throughout lessons, assessments, and my classroom environment. I also want to learn more about grounding and meditation practices to use in early education as well as play lessons.

With this insight, I will commit to taking better care of myself — mentally, emotionally, and physically — so that I can sustainably do the work of developing decolonized histories in my district. Prioritizing my wellness will allow me to lead with clarity, purpose, and strength, just as Erika Huggins modeled.

I am envisioning talking about Ericka with my students and connecting the Black Lives Matter Principles I already talk with my students about with the Black Panther Party 10-Point Program. Sharing her message of intentionally healing from the inside out. I also will highlight her in GSA (gender and sexuality alliance) and what “queer” meant to her.

How was the format for the class?

Great format! The well-balanced questions and sharing in the first half, followed by an excellent breakout group, is top notch. I appreciate that resources will be shared later because today I was too focused on the workshop to keep up with the chat.

Love the format just as it is.

Excellent interview and discussion format.

Honestly everything felt perfect and flowed.

It always works. Don’t change a thing.

Wonderfully planned and executed!

I thought this ran extremely smoothly. I was so impressed with the facilitators.

I loved the breakout groups. I found it very helpful to hear from other teachers and past teachers to help build my own future classroom and be able to create an environment where everyone feels heard and understood.

I found the format to be supportive and accessible. I am autistic and sometimes have a hard time with breakout rooms, but having a facilitator in the room made it such a positive and inclusive experience. I really appreciated the inclusion of ASL interpretation and other details that made this workshop accessible. I thought the workshop was the perfect length and it was very well-structured. Thank you for the intentionality.

Everything worked and I am totally inspired as always.

Presenters

Mary Phillips is an associate professor the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Her interdisciplinary research agenda focuses on race and gender in post-1945 social movements and the carceral state, and her research areas include the Modern Black Freedom Struggle, Black Feminism, and Black Power Studies. Outside of the academy, her essays have been featured in the Huffington Post, Ms. Magazine blog, New Black Man (in Exile), Colorlines, Vibe Magazine, Black Youth Project, and the African American Intellectual History Society’s blog, Black Perspectives.

Cierra Kaler-Jones is the executive director of Rethinking Schools. Cierra is also on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project, which Rethinking Schools coordinates with Teaching for Change, and has hosted many of our Teach the Black Freedom Struggle classes. Cierra is a teacher, a dancer, a writer, and a researcher. She previously served as director of storytelling at the Communities for Just Schools Fund.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing, author of Teach Truth: The Struggle for Antiracist Education, and Zinn Education Project campaign director.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn