Update: On Sept. 16, 2018, Slate published an essay by Sam Wineburg, “Howard Zinn’s Anti-Textbook: Teachers and students love A People’s History of the United States. But it’s as limited—and closed-minded—as the textbooks it replaces.”

The essay is from a chapter in Wineburg’s new book, Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone), released this week by University of Chicago Press. The essay at Slate draws on many of the same arguments Wineburg made in 2012 in “Undue Certainty: Where Howard Zinn’s A People’s History Falls Short” in AFT’s American Educator.

For example, in both essays Wineburg overblows the use and impact of A People’s History of the United States. He claims the book is mainstream and that many teachers assign it as the only history text. He accuses Zinn of not using footnotes, while not providing any evidence for his own claims. He also implies that teachers use A People’s History of the United States uncritically, as a text for students to read and memorize. This is insulting to teachers across the country who plan lessons that involve multiple sources, critical literacy, and historical inquiry. Close to 84,000 teachers have signed up to access people’s history lessons from the Zinn Education Project website over the past ten years and at least 25 more sign up every day. The lessons they access are interactive and draw on countless books, primary documents, and oral histories.

The article below by Alison Kysia, written while a fellow with the Zinn Education Project, is a response to “Undue Certainty: Where Howard Zinn’s A People’s History Falls Short.” Much of Kysia’s critique of that article is relevant to the latest one by Wineburg in Slate.

By Alison Kysia

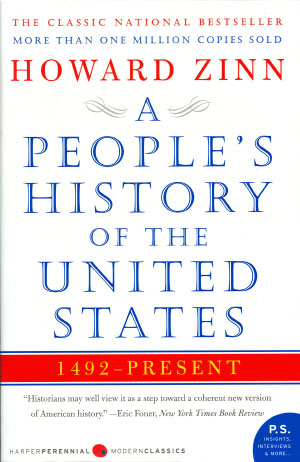

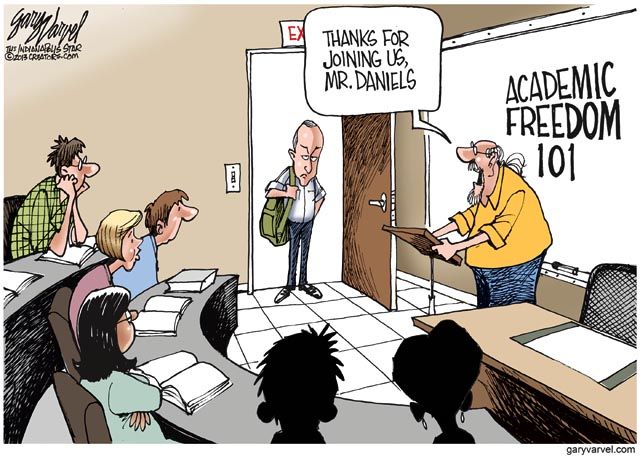

Since the death of historian Howard Zinn in 2010, a number of scholars and politicians have targeted Zinn’s work in an effort to undermine his influence among educators. Most famously, former Indiana Governor Mitch Daniels celebrated Zinn’s death in emails to his education lieutenants and ordered them to find and remove Zinn’s book, A People’s History of the United States, from schools and teacher education programs.[1] Peter Wood, president of the National Association of Scholars, writing for the Chronicle of Higher Education, applauded Daniels’ attempts at censorship when he said: “Daniels’s four e-mails . . . are a window into the frustration of American conservatives with the quotidian anti-Americanism of the academy.”[2] Wood goes on to reference Sean Wilentz, a professor of history at Princeton University, in a statement he wrote for the Los Angeles Times after Zinn’s death, disparaging his work: “What he [Zinn] did was take all of the guys in white hats and put them in black hats, and vice versa.”[3]

Since the death of historian Howard Zinn in 2010, a number of scholars and politicians have targeted Zinn’s work in an effort to undermine his influence among educators. Most famously, former Indiana Governor Mitch Daniels celebrated Zinn’s death in emails to his education lieutenants and ordered them to find and remove Zinn’s book, A People’s History of the United States, from schools and teacher education programs.[1] Peter Wood, president of the National Association of Scholars, writing for the Chronicle of Higher Education, applauded Daniels’ attempts at censorship when he said: “Daniels’s four e-mails . . . are a window into the frustration of American conservatives with the quotidian anti-Americanism of the academy.”[2] Wood goes on to reference Sean Wilentz, a professor of history at Princeton University, in a statement he wrote for the Los Angeles Times after Zinn’s death, disparaging his work: “What he [Zinn] did was take all of the guys in white hats and put them in black hats, and vice versa.”[3]

Arguably, the most thorough attack on Zinn appeared in the American Educator. In the article, “Undue Certainty: Where Howard Zinn’s A People’s History Falls Short,”[4] Sam Wineburg, professor of education at Stanford University, insists that Zinn’s work is just as problematic as traditional textbooks in that “A People’s History and traditional textbooks are mirror images that relegate students to similar roles as absorbers—not analysts—of information, except from different points on the political spectrum.”[5] Zinn succeeds at relegating students to a position of passivity, according to Wineburg, by manipulating the historical record to fit his ideological perspective—a people’s history, the deliberate inclusion of perspectives ignored in histories that celebrate power. Wineburg contends that Zinn cannot practice honest scholarship precisely because of this perspective—that an ideological commitment to a people’s history necessarily reduces students to a leftist but no less totalitarian mindset. For these reasons, Wineburg warns, educators should be careful about using Zinn’s work in the classroom.

Although Wineburg is not the only critic of Zinn, he is nevertheless significant and less susceptible to easy dismissal. His academic credentials and accessible writing style bolster his credibility. He is a university professor and has published a number of academic books and articles on teaching history. Wineburg’s well-cited arguments and use of history are elegant enough to plant seeds of doubt among readers, opening up the possibility that Zinn was, in fact, being manipulative. Wineburg’s critique gains further credibility through his publication in the American Educator, the journal of the American Federation of Teachers, which boasts 1.5 million members.

Although Wineburg is not the only critic of Zinn, he is nevertheless significant and less susceptible to easy dismissal. His academic credentials and accessible writing style bolster his credibility. He is a university professor and has published a number of academic books and articles on teaching history. Wineburg’s well-cited arguments and use of history are elegant enough to plant seeds of doubt among readers, opening up the possibility that Zinn was, in fact, being manipulative. Wineburg’s critique gains further credibility through his publication in the American Educator, the journal of the American Federation of Teachers, which boasts 1.5 million members.

Because Howard Zinn was a leading advocate of a grassroots historical perspective—one that inspires educators to rethink and revise their curricula—an attack on Zinn is a way of discouraging educators from teaching a people’s history. Thus, it’s worth subjecting Wineburg’s critique to careful scrutiny.

Zinn’s ‘Mainstream’ History

Wineburg argues that a thorough critique of Zinn is necessary because A People’s History is the most popular history textbook being used in U.S. classrooms today. For as much as I wish this were true, it isn’t. Wineburg contends that Zinn’s A People’s History has unprecedented influence on American readers and has gone “mainstream”: from the 2 million copies sold, to its ranking on Amazon.com, to references made from the likes of Matt Damon and Tony Soprano.[6] Wineburg states, “In the last 30 years . . . A People’s History has arguably had a greater influence on how Americans understand their past than any other single book.”[7] Wineburg claims that Zinn’s work has become a standard text among K-12 social studies teachers. He cites four syllabi from teacher training courses that include Zinn’s A People’s History to show that Zinn’s work is “a perennial favorite in courses for future teachers.”[8]

The problem with this argument is evidence. He does not include the number of K-12 teacher training courses offered in the United States in any given year. Given that there were more than 3 million elementary and middle school teachers in the United States as of the 2010 census, four syllabi are less than representative.[9] To the best of my knowledge, there have not been any studies to determine the texts most often assigned in K-12 U.S. history or social studies courses. One study evaluated the syllabi of 258 undergraduate U.S. history survey courses taught in spring 2004 and found that only three included Zinn’s A People’s History—or just over 1 percent.[10] Arguing that Zinn’s work has become the dominant narrative on U.S. history is factually untenable. Therefore such statements on Zinn’s impact are unverifiable without the use of anecdotal evidence, a criticism that Wineburg makes of Zinn’s work.[11]

That is not to say that Zinn has not been influential. There are many educators who enthusiastically use Zinn in the classroom. The Zinn Education Project, formed in 2008, designs and disseminates curriculum that supports the work of Zinn; there are currently 33,000 teachers registered to download teaching resources from their website.[12] Nevertheless, there is no evidence that A People’s History of the United States is the new U.S. history textbook of choice in schools across the country.

More importantly, the crux of Wineburg’s critique questions Zinn’s scholarly rigor, a weakness that he claims is reinforced by Zinn’s commitment to a people’s history. Wineburg focuses much of his attention on Zinn’s handling of World War II. Wineburg analyzes three of Zinn’s arguments: the utility of the moniker “people’s war” to describe WWII and the degree to which black Americans resisted the war; a comparison of German and Allied bombing campaigns and Zinn’s chronological references to those campaigns; and the United States’ use of two atomic bombs at the end of WWII. It is useful to read Wineburg’s critiques side by side with Zinn’s work in order to evaluate the veracity of his claims.

The Meaning of ‘People’s War’ and Black American Resistance

Wineburg decontextualizes or ignores Zinn’s statements throughout chapter 16 in order to sow doubt about the evidence Zinn uses. Wineburg initially acknowledges Zinn’s embrace of the popular reference to WWII as “a people’s war,” meaning that it was supported by a majority. As Zinn explains, “By certain evidence, it was the most popular war the United States ever fought,” including the 18 million people who participated in the armed services as well as the 25 million workers who bought war bonds.[13] Wineburg fails to include the analytical questions Zinn goes on to ask: “But could this be considered a manufactured support, since all of the power of the nation—not only the government, but the press, the church, and even the chief radical organizations—was behind the calls for all-out war? Was there an undercurrent of reluctance; were there unpublicized signs of resistance?”[14] Zinn is asking students to think outside of the “majority” box, to look for signs of resistance even when the war drums are beating the loudest. Zinn states that “these questions deserve thought,” language that does not coerce students to make any specific conclusions about history, but rather to think critically about who writes and defines history. These kinds of questions reveal the power of people’s history to engage students in the politics of telling stories of the past.

Wineburg decontextualizes or ignores Zinn’s statements throughout chapter 16 in order to sow doubt about the evidence Zinn uses. Wineburg initially acknowledges Zinn’s embrace of the popular reference to WWII as “a people’s war,” meaning that it was supported by a majority. As Zinn explains, “By certain evidence, it was the most popular war the United States ever fought,” including the 18 million people who participated in the armed services as well as the 25 million workers who bought war bonds.[13] Wineburg fails to include the analytical questions Zinn goes on to ask: “But could this be considered a manufactured support, since all of the power of the nation—not only the government, but the press, the church, and even the chief radical organizations—was behind the calls for all-out war? Was there an undercurrent of reluctance; were there unpublicized signs of resistance?”[14] Zinn is asking students to think outside of the “majority” box, to look for signs of resistance even when the war drums are beating the loudest. Zinn states that “these questions deserve thought,” language that does not coerce students to make any specific conclusions about history, but rather to think critically about who writes and defines history. These kinds of questions reveal the power of people’s history to engage students in the politics of telling stories of the past.

Wineburg confuses the reader by initially agreeing that Zinn embraces the concept of “a people’s war,” but then argues that Zinn overstates black American resistance to the war in an attempt to prove that Zinn is manipulating historical evidence. Wineburg fixates on Zinn’s use of the word “widespread”[15] to describe black resistance to the war and accuses Zinn of inflating black disillusionment. Wineburg states:

He [Zinn] asserts that black Americans restricted their support to a single V: the victory over racism. As for the second V, victory on the battlefields of Europe and Asia, Zinn claims that an attitude of “widespread indifference, even hostility,” typified African Americans’ stance toward the war. Zinn hangs his claim on three pieces of evidence: (1) a quote from a black journalist that “the Negro . . . is angry, resentful, and utterly apathetic about the war”; (2) a quote from a student at a black college who told his teacher that “the Army jim-crows us. The Navy lets us serve only as messmen. The Red Cross refuses our blood. Employers and labor unions shut us out. Lynchings continue”; and (3) a poem called the “Draftee’s Prayer,” published in the black press: “Dear Lord, today / I go to war: / To fight, to die,/Tell me what for? / Dear Lord, I’ll fight, / I do not fear, / Germans or Japs; / My fears are here. / America!”[16]

Wineburg is correct that Zinn says, “There seemed to be widespread indifference, even hostility, on the part of the Negro community to the war despite the attempts of Negro newspapers and Negro leaders to mobilize black sentiment.”[17] However, Wineburg does not include what Zinn says on the next two pages. He also deleted the first few words of Zinn’s quote that begins with “there seemed to be . . . ,” language that qualifies what comes next. Neither does Wineburg include the beginning of the next paragraph where Zinn states that despite the examples of black indifference and hostility to the war, “There was no organized Negro opposition to the war.”[18] In these few sentences alone Zinn does not portray a monolithic black community that is wholly disenchanted and disengaged with the war, but rather one in which there were those who served in the armed services, others who expressed discontent despite a general lack of mobilization against the war, and those who actively resisted. Zinn’s language is restrained when describing antiwar activism. For example, he says, “a few small anarchist and pacifist groups refused to back the war. . . ,” and “only one organized socialist group opposed the war unequivocally.”[19] Zinn goes on to say that “the vast bulk of the American population was mobilized, in the Army, and in civilian life, to fight the war.”[20] Zinn is not arguing that there was widespread indifference or hostility in the black community or within the larger American community. If we read Wineburg’s article without Zinn side by side, it is easy to take Wineburg’s critique at face value and assume that Zinn was making untenable statements about black resistance to WWII.

While Wineburg is busy restructuring Zinn’s argument he misses the point of a people’s history: to highlight minority voices in order to encourage students today to speak up for justice even when the majority discourages dissent and silences debate. Wineburg picks and chooses Zinn’s evidence and quotes in a way that frames Zinn as purely an ideologue rather than a competent scholar. By presenting Zinn’s work in this way, he creates doubt in the minds of educators about the integrity of Zinn’s work. What is interesting is what Wineburg does not include from Zinn’s chapter—the quotes that reveal the real power of a people’s history. In doing this, Wineburg uses the issue of “evidence” as a way of discrediting the essential questions Zinn wants us to think about in the study of history. Zinn asks us to rethink majority behavior and patriotic sloganeering, to look both deeper and within the margins of community to find resistance, to reevaluate the efficacy of choices of the past in order to prepare us to make our own choices today and in the future.

While Wineburg is busy restructuring Zinn’s argument he misses the point of a people’s history: to highlight minority voices in order to encourage students today to speak up for justice even when the majority discourages dissent and silences debate. Wineburg picks and chooses Zinn’s evidence and quotes in a way that frames Zinn as purely an ideologue rather than a competent scholar. By presenting Zinn’s work in this way, he creates doubt in the minds of educators about the integrity of Zinn’s work. What is interesting is what Wineburg does not include from Zinn’s chapter—the quotes that reveal the real power of a people’s history. In doing this, Wineburg uses the issue of “evidence” as a way of discrediting the essential questions Zinn wants us to think about in the study of history. Zinn asks us to rethink majority behavior and patriotic sloganeering, to look both deeper and within the margins of community to find resistance, to reevaluate the efficacy of choices of the past in order to prepare us to make our own choices today and in the future.

Wineburg continues this critique by claiming that Zinn neglects precious information that would provide a more honest assessment of black American attitudes toward WWII. For example, Wineburg claims that Zinn omits the number of conscientious objectors to WWII; his argument is that if Zinn had included these numbers then the reader would see that there was a disproportionately low representation of African Americans among conscientious objectors, thus proving that African Americans were not as disenchanted with the war as Zinn would like us to believe.[21] Wineburg states that black draft refusal was as low as 4.4 percent of all Justice Department cases of refusal.[22] This line of reasoning is problematic. There is no direct correlation between draft refusal and support for war; many draftees may not want to fight but nevertheless report for duty due to a variety of reasons. Wineburg does not inform the reader about the complex and expensive process of being certified as a conscientious objector.[23] Nor does Wineburg acknowledge the emotional, financial, and political repercussions of a black man resisting the draft or publicly challenging the morality of the war while living in the Jim Crow United States. He is conflating draft refusal with conscientious objection, which are not the same categories. Draft refusal could include a wide variety of antiwar activities. Wineburg’s history is one of collecting statistics without commentary, as if the statistics are inherently objective. Teaching from the perspective of a people’s history, on the other hand, is a way of analyzing historical information and asking critical questions that reveal relationships of power.

Comparing German and Allied Bombing During WWII

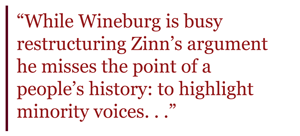

TOP: German bombers set the whole inner city of Rotterdam ablaze, killing 814 of its inhabitants. BOTTOM: City center following the Coventry Blitz of November 14 and 15, 1940. Images: Wikimedia Commons.

Another example from Zinn’s chapter on WWII that Wineburg challenges is Zinn’s treatment of German and Allied bombings during WWII and his chronology of those events. Wineburg argues that Zinn uses “a slippery timeline,”[24] questioning his competence as a historian. He accuses Zinn of “chronological bait and switch,” arguing that Zinn is playing “fast and loose with historical context,” in order to convince the reader to condemn U.S. participation in WWII. Wineburg states that “Zinn’s point is clear: before we wag an accusing finger at the Nazis, we should take a long hard look in the mirror.”[25] Wineburg cuts and pastes parts of Zinn’s argument, confusing the reader while misrepresenting Zinn. Reading Zinn’s chapter next to Wineburg’s critique gives us the opportunity to critically investigate these accusations, while also seeing that the real target here is not “evidence” as much as it is a people’s history.

Wineburg questions Zinn’s comparison of German and Allied bombings in WWII, and by extension Zinn’s implication that readers should take a closer look at the “us-versus-them” dichotomy of war. Zinn cites the German bombings of Rotterdam, Holland and Coventry, England in 1940, noting President Roosevelt’s criticism of those bombings for their brutality, yet later followed in 1943-45 by Allied saturation bombings of German cities.[26] Zinn also references the United States’ bombing campaigns in Japan, including the use of two atomic bombs[27] and reflects on the importance of these comparisons in A People’s History:

There was a mass base of support for what became the heaviest bombardment of civilians ever undertaken in any war: the aerial attacks on German and Japanese cities. One might argue that this popular war support made it a “people’s war.” But if “people’s war” means a war of people against attack, a defensive war—if it means a war fought for humane reasons instead of for the privilege of an elite, a war against the few, not the many—then the tactics of all-out aerial assault against the populations of Germany and Japan destroy that notion.[28]

Wineburg here is correct: Zinn is asking us to think critically about the meaning behind catchy slogans like “a people’s war.” Although Wineburg does not explicitly make the accusation, Zinn is not arguing that the Allied forces were just as bad as the Axis powers, nor is he excusing the German-led genocide campaigns of WWII or claiming that ending those genocides was irrelevant. Rather, he is addressing the hypocrisy implicit in most textbook treatments of WWII—that the Germans were monsters and Americans and Brits were the saviors; a just fight of good vs. evil.

Who are “the people” in “a people’s war”? Zinn asks us to think about civilian casualties, to think about the Unpeople,[29] the majority of dead in this war and every other one who are overwhelmingly civilians, the ones who are killed en masse and become mere statistics, recorded in books and shelved for future research. Zinn wants us to think about war as more than a sports event between “our” team and the “other” team but rather as choices with consequences—human consequences. Zinn’s use of historical evidence here is appropriate. These are exactly the questions we need to ask when living in a society based on a war economy and even more pertinent after a 12-year-long “War on Terrorism.”

Who are “the people” in “a people’s war”? Zinn asks us to think about civilian casualties, to think about the Unpeople,[29] the majority of dead in this war and every other one who are overwhelmingly civilians, the ones who are killed en masse and become mere statistics, recorded in books and shelved for future research. Zinn wants us to think about war as more than a sports event between “our” team and the “other” team but rather as choices with consequences—human consequences. Zinn’s use of historical evidence here is appropriate. These are exactly the questions we need to ask when living in a society based on a war economy and even more pertinent after a 12-year-long “War on Terrorism.”

Sloppy Scholarship

Wineburg continues to challenge Zinn’s historical acumen by questioning his use of a basic chronological timeline in relation to some of the aforementioned bombing campaigns. He derides Zinn’s presentation of the Dresden bombing: “[Zinn] begins his claim with the phrase ‘at the start of WWII,’ but the Dresden raid occurred five years later, in February 1945, when all bets were off and long-standing distinctions between military targets (“strategic bombing”) and civilian targets (“saturation bombing”) had been rendered irrelevant.”[30] If you go back to A People’s History you will see that Zinn says, “The climax of this terror bombing was the bombing of Dresden in early 1945. . .”[31] Zinn clearly states the year of the Dresden bombing. Wineburg is either ignoring what Zinn actually wrote or is practicing sloppy scholarship. More importantly, Wineburg’s assertion that the distinctions between military and civilian targets were irrelevant is exactly the kind of statement that Zinn wants us to critically analyze. Such distinctions are figments of a militaristic imagination that then get recorded in state-sponsored history textbooks and regurgitated as facts, leaving citizens without the intellectual tools necessary to think critically about how the government frames current and future war rhetoric.

Wineburg continues to challenge Zinn’s historical acumen by questioning his use of a basic chronological timeline in relation to some of the aforementioned bombing campaigns. He derides Zinn’s presentation of the Dresden bombing: “[Zinn] begins his claim with the phrase ‘at the start of WWII,’ but the Dresden raid occurred five years later, in February 1945, when all bets were off and long-standing distinctions between military targets (“strategic bombing”) and civilian targets (“saturation bombing”) had been rendered irrelevant.”[30] If you go back to A People’s History you will see that Zinn says, “The climax of this terror bombing was the bombing of Dresden in early 1945. . .”[31] Zinn clearly states the year of the Dresden bombing. Wineburg is either ignoring what Zinn actually wrote or is practicing sloppy scholarship. More importantly, Wineburg’s assertion that the distinctions between military and civilian targets were irrelevant is exactly the kind of statement that Zinn wants us to critically analyze. Such distinctions are figments of a militaristic imagination that then get recorded in state-sponsored history textbooks and regurgitated as facts, leaving citizens without the intellectual tools necessary to think critically about how the government frames current and future war rhetoric.

Wineburg continues to question Zinn’s grasp of a basic timeline, stating that “people familiar with the chronology of WWII immediately sense a disjuncture between the phrase ‘at the start of WWII’ and the date of the Coventry raid,” which Wineburg reminds us is 1940. However, WWII lasted from 1939 to 1945 which begs the question of what the proper use of the phrase “at the start. . .” is. Is referencing something that happened one year after the beginning of a six-year war really a sign of flagrant scholarly abuse? When we deconstruct Wineburg’s arguments piece by piece, the structure falls quickly.

Continuing his critique of Zinn’s treatment of WWII, Wineburg accuses Zinn of being silent on Poland, and through this omission, denying the reader the ability to appropriately assess Nazi terrorism. Wineburg is right: Zinn left out any reference to Poland. But it does not matter, because Zinn is not arguing that the Nazis were peaceniks, nor is he attempting to write a complete history of WWII. Zinn states at the very beginning of the chapter:

It was a war against an enemy of unspeakable evil. Hitler’s Germany was extending totalitarianism, racism, militarism, and overt aggressive warfare beyond what an already cynical world had experienced. And yet, did the governments conducting this war—England, the United States, the Soviet Union—represent something significantly different, so that their victory would be a blow to imperialism, racism, totalitarianism, militarism, in the world?[32]

Zinn is not asking us to excuse Hitler or the Nazis. He is not asking us to ignore genocide. He is asking us to think about our own nation’s history and the ways we create and support terrorism, racism, and militarism. He is asking us to reject the moral posturing that afflicts war histories in power-centric history textbooks. These are vitally important perspectives we need to encourage students of history to consider.

Atomic Bombs

Lastly, on the issue of WWII, Wineburg takes issue with Zinn’s presentation of the United States’ dropping of two atomic bombs on Japan. Wineburg claims that “[Zinn’s] goal is to demolish the narrative learned in high school: that faced with the prospect of the entire Japanese nation hunkered down in underground bunkers and holed up in caves, the United States dropped the bomb (sic) with profound remorse and only then as a last resort.”[33]

First, it is important to note that Wineburg refers to the bomb in singular throughout this section of the article, when in fact two atomic bombs were dropped: one on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945 and the other on Nagasaki on August 9, 1945. Nevertheless, Wineburg is critical of Zinn’s reliance on just two “revisionist” scholars: Gar Alperovitz’s Atomic Diplomacy (1967) and Martin Sherwin’s A World Destroyed (1975). If you go back to Zinn’s arguments on WWII, you will see that he incorporated additional sources, including a report by the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, set up by the War Department, which challenged the necessity of dropping the bombs—a source that cannot be dismissed as “revisionist.”[34] Wineburg is ultimately criticizing Zinn’s argument that the U.S. did not have to drop the bombs to stop the war but rather chose to use the bombs for other strategic purposes. Zinn’s argument is firmly within the realm of mainstream academic debate and we can list scholars who argue both perspectives.[35]

The more relevant question is whether or not Zinn is being irresponsible as a scholar for not presenting both points of view. I argue no. Zinn introduces his discussion of the atomic bombs by stating, “The justification for these atrocities was that this would end the war quickly, making unnecessary an invasion of Japan. Such an invasion would cost a huge number of lives, the government said—a million, according to Secretary of State Byrnes; half a million, Truman claimed was the figure given him by General George Marshall.”[36] Zinn’s point is to challenge the dominant narrative of justification, which he describes.

Wineburg, communicated through his silence on the significance of a people’s history, does not want students to spend too much time thinking about the messy aspects of history: people. He is arguing that the most important message that students take away from the story of the United States dropping bombs on Japanese civilians is the inability of the U.S. government to make any other logical choice. He is emphatic about this point, but utterly silent on the necessity for students to understand the human cost of that decision, how it killed and maimed children, and burned bodies past the point of recognition, even vaporizing some, how it poisoned the water and soil and created long-term birth defects. I want my students to immediately conjure up these images when our government comes knocking for the next war, so that they are equipped to make conscientious choices about their role in subsequent conflicts rather than ignoring such debates as the same empty abstractions they talk about in history classes.

Wineburg, communicated through his silence on the significance of a people’s history, does not want students to spend too much time thinking about the messy aspects of history: people. He is arguing that the most important message that students take away from the story of the United States dropping bombs on Japanese civilians is the inability of the U.S. government to make any other logical choice. He is emphatic about this point, but utterly silent on the necessity for students to understand the human cost of that decision, how it killed and maimed children, and burned bodies past the point of recognition, even vaporizing some, how it poisoned the water and soil and created long-term birth defects. I want my students to immediately conjure up these images when our government comes knocking for the next war, so that they are equipped to make conscientious choices about their role in subsequent conflicts rather than ignoring such debates as the same empty abstractions they talk about in history classes.

The Facade of Evidence

Wineburg’s entire critique rests on the argument that Zinn was a sloppy historian precisely because of his commitment to a people’s history. Wineburg uses the facade of “evidence” to argue that a people’s history is an untenable project that cannot support the real facts of history. He is criticizing a people’s history perspective as inherently subjective, i.e., leftist and therefore not grounded in objective history that presents all possible arguments about any given event. Yet Zinn never claims to be writing from the purported position of objectivity. In the first chapter of A People’s History, Zinn makes this clear:

My viewpoint, in telling the history of the United States, is different: that we must not accept the memory of states as our own. Nations are not communities and never have been. The history of any country, presented as the history of a family conceals fierce conflicts of interest (sometimes exploding, most often repressed) between conquerors and conquered, masters and slaves, capitalists and workers, dominators and dominated in race and sex. And in such a world of conflict, a world of victims and executioners, it is the job of thinking people, as Albert Camus suggested, not to be on the side of the executioners. Thus, in that inevitable taking of sides which comes from selection and emphasis in history, I prefer to try and tell the story of the discovery of America from the viewpoint of the Arawaks, of the Constitution from the standpoint of slaves, of Andrew Jackson as seen by the Cherokees, of the Civil War as seen by the New York Irish, . . .the Second World War as seen by pacifists. . . .[37]

Zinn’s goal is to provide alternative viewpoints and to make readers think critically about the “official” version of stories as well as the alleged neutrality of textbooks. To assume that readers of Zinn do not understand where he is coming from or cannot read his work critically is patronizing. Wineburg decontextualizes what Zinn wrote to argue that he did not write the book he never claimed to be writing.

Next, Wineburg zeroes in on what he claims is Zinn’s use of imprecise and influential language, unduly prompting the reader to arrive at a specific conclusion about the use of the bombs. He says:

Anyone who raises the possibility of a negotiated peace versus an unconditional surrender is playing the game that historians call the counterfactual, a thought experiment about how the past might have turned out had things not happened as they did. Its game pieces are if, may, might (Wineburg’s italics). . . . The counterfactuals’ qualifiers and second-guesses convey the modesty one is obliged to adopt when conjuring up a past that did not occur. But when Zinn plies the counterfactual, he seems to know something no one else knows—including historians who’ve given their professional lives to the topic: “If only the Americans had not insisted on unconditional surrender—that is, if they were willing to accept one condition to the surrender, that the Emperor, a holy figure to the Japanese, remain in place—the Japanese would have agreed to stop the war.” Not might have, not may have, not could have. But “would have agreed to stop the war.” Not only is Zinn certain about the history that’s happened. He’s certain about the history that didn’t.[38]

Wineburg is correct: Zinn does include this exact quote in chapter 16, and there is indeed no way to prove such a statement, and Zinn could have used a better qualifier. So far in Wineburg’s entire critique, this is the first example he provided that has merit—the absence of one qualifier in one sentence in a 600-plus-page book.

The Danger of Thinking

The ideological point that Wineburg seems to be making is that it is dangerous to allow students to think that political decisions of the past were choices and not “facts.” Having used Zinn in my classrooms for years, this is precisely the consciousness-raising power of a people’s history: alternative viewpoints shed light on perspectives we are not privy to in the typical obedient narratives of state-sponsored histories. I want my students to contemplate the possibilities for alternative readings of history and apply those same processes when evaluating world events today.

The ideological point that Wineburg seems to be making is that it is dangerous to allow students to think that political decisions of the past were choices and not “facts.” Having used Zinn in my classrooms for years, this is precisely the consciousness-raising power of a people’s history: alternative viewpoints shed light on perspectives we are not privy to in the typical obedient narratives of state-sponsored histories. I want my students to contemplate the possibilities for alternative readings of history and apply those same processes when evaluating world events today.

The larger issue of not just Wineburg’s critique but the persistent vilification of Zinn is the attempt to create doubt about Zinn’s qualifications as an historian in order to challenge the entire people’s history project. Although Wineburg exaggerates the influence of Howard Zinn and A People’s History of the United States in schools, no doubt there are many who would prefer Zinn be entirely scrubbed from the curriculum. The content of today’s textbooks are controlled by those with power: corporate, political, and religious leaders whose worldview—that Great Leaders make history, capitalism is freedom, dissent is permissible only in designated spaces—is well represented in mainstream texts. Howard Zinn’s work represents a fundamental challenge to this worldview. Thus, the attacks on Zinn, that seem increasingly shrill, are not simply about one historian or even one’s approach to history, but are really about one’s hope for the kind of society we want to live in—and how we might get there.

‘TRUTH’ and Fascism

Wineburg’s language toward the end of his essay becomes more desperate. He paints a picture in which Zinn, through his books, is able to exert a nefarious influence on his readers. Weinberg supplies a series of nameless Amazon.com reviews of Zinn’s book as proof of the zealotry that Zinn inspires in readers. For example, one reviewer, referred to as gmt903, wrote in her or his Amazon.com review that Zinn’s book was the “TRUTH” and in Wineburg’s estimation this is valid, scholarly evidence of Zinn’s dangerous power. Again, it is important to ask what Wineburg isn’t using as evidence in his critique. For example, while he has time to analyze anonymous Amazon.com reviews, he chooses to skip the Howard Zinn papers currently housed at New York University’s Tamiment Library, including letters sent to Zinn from students and teachers describing the impact of his work on their understanding of history. New York University Professor Robert Cohen read these letters and found that students and teachers overwhelmingly embrace Zinn’s work, provoking healthy historical debate even among those who do not support Zinn’s politics per se. For example, Cohen says:

Students who disagreed with Zinn’s radical take on history, no less than those who agreed with him, tended to find these sessions intellectually stimulating since Zinn’s writing was so accessible and his ideas so new to them. As [one teacher] told Zinn, “Over the course of the school year, no matter if a student ‘loved’ you or ‘hated’ you, they all looked forward to what you had to say on a topic.”

Cohen cites a student who wrote to Zinn: “Your writings are very educational. They help us to think about a side of history that we usually aren’t exposed to. Until I read one of your writings I never even stopped to think about the fact that our history [text] books were only giving us one viewpoint. . . . I didn’t realize that there were so many controversial happenings to be written about.” Cohen goes on to note that “The students were making their first moves towards recognizing that history was more than a simple trivia game involving remembering names and dates, that history was a critical discipline.”[39] In contrast to anonymous reviewers, these letters convey how clearly Zinn’s history illustrates the politics of writing history, while increasing students’ ability to critically analyze historical arguments and evidence.

Wineburg then uses the F-word—fascism—to describe Zinn’s influence. Wineburg argues, “A history of unalloyed certainties is dangerous because it invites a slide into intellectual fascism. History as truth, issued from the left or from the right, abhors shades of gray.”[40] After reading and teaching Zinn for many years, I do not see history as simply a matter of extremes, and using the word fascism to describe the influence Zinn has on readers is a desperate attempt at demonizing a people’s history.

Zinn’s language throughout the book does not impose an either/or duality upon the study of history. Reading A People’s History encourages students to talk back to the history they are given, regardless of the ideological perspective of the author—to think about what information is not included in a historical story, to ask which chapters of history books are wholly left out, to investigate perspectives that are ignored or silenced. A people’s history is about asking questions, challenging authority and the abuse of power, discovering the everyday women and men who fight for a more inclusive and just society, looking for heroes outside of those who are commemorated on holidays. These are the lessons I have learned from work like Zinn’s and the lessons I want my students to master.

Zinn’s language throughout the book does not impose an either/or duality upon the study of history. Reading A People’s History encourages students to talk back to the history they are given, regardless of the ideological perspective of the author—to think about what information is not included in a historical story, to ask which chapters of history books are wholly left out, to investigate perspectives that are ignored or silenced. A people’s history is about asking questions, challenging authority and the abuse of power, discovering the everyday women and men who fight for a more inclusive and just society, looking for heroes outside of those who are commemorated on holidays. These are the lessons I have learned from work like Zinn’s and the lessons I want my students to master.

Having taken Wineburg’s concerns seriously, I am confident in my continued use of Zinn’s work in my classroom, as one of many solid sources in teaching a people’s history.

Alison Kysia has taught history at Northern Virginia Community College for six years. She has been an educator for more than 15 years. Special thanks to Bill Bigelow for his thoughtful comments and suggestions.

Comments are closed.