On November 18, 2024, filmmaker Yoruba Richen and historian LeRae Umfleet spoke with Jesse Hagopian about American Coup: Wilmington 1898, a new American Experience PBS documentary directed by Richen and Brad Lichtenstein that examines a white supremacist massacre of Black residents of Wilmington, North Carolina.

In this excerpt from the class, Yoruba Richen describes Reconstruction as one of the most unexamined and most consequential periods of U.S. history, exemplified by the story of Wilmington.

Participants shared what they learned and additional reflections on the session:

The entire story of the Wilmington massacre and coup. I’d never learned about it before, and hearing the context, the events of the day, and the role of the news was incredibly moving and timely.

It is always so powerful to learn about another hidden piece of history, particularly stories of empowerment, success, and multiracial communities. What a loss to have not been taught these parts of our history as children. The fact that we are continuing to repeat this history — using the media to spread disinformation, lies, and distortions — is so terrible.

The extent of the coup to regain the power of white supremacy in Wilmington on every level — economic and political — was new to me.

The connections to today, and current politics, are frightening and should be a wake-up call. They highlight how important it is for these stories to be told so we as a country are aware of the possibility of and danger to democracy.

The inclusion of descendants — both victims and perpetrators — makes this history relevant and sparks fruitful discussion.

The story behind the story of Reconstruction. It’s really heartbreaking how little they teach us about our history.

I think this class crystallized the ways in which we need to be constantly broadening the spectrum of U.S. history to include diverse perspectives that have long been minimized or altogether left out.

Though I do not have my own classroom at this time, I share these stories with students whenever I get the chance. I like to confirm for them that there is a long history of being strong, successful, and whole, even amidst so many oppressive efforts.

Watch Documentary

The film is streaming for free on American Experience PBS.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Welcome to you all. Let’s dive into this discussion of the documentary American Coup: Wilmington 1898, which is now streaming online and on the PBS app. I’m extremely happy to welcome documentary filmmaker Yoruba Richen and historian LeRae Umfleet.

Yoruba Richen is the founding director of the documentary program at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York. She is an award-winning documentary filmmaker, including The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, that we had the honor of developing lessons for. An incredible film that I’m deeply grateful for.

We’re also joined by historian LeRae Umfleet, who produced a legislative report for the 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Commission of 2005. In 2009, the report was published as a book, A Day of Blood: The 1898 Wilmington Race Riot.

So, first I just want to say congratulations on this incredible new film. Even though it’s about events in 1898, it’s so timely. I knew a rough outline of these events, but watching the film, it really made me realize how fundamental these events are to being racially literate in our society today. So thank you for highlighting this history and making it so relevant.

I want to begin by asking about the context to those events, because I think we have to understand the era of Reconstruction to be able to understand what happened in 1898. So maybe you could talk about both the strides toward multiracial democracy and the backlash of white supremacy that happened during this period that people often don’t learn in school, but it’s crucial for understanding the context.

Yoruba Richen: Well, I’ll start. First off, it’s so great to be here. We’ve really been looking forward to this, and it’s so great to see folks from all over the world, and all over the country, certainly. So it’s very cool. I have been saying in our screening tour that Reconstruction is one of the most unexamined periods in our history — obviously, you guys are trying to change that, which is great — but also one of the most consequential.

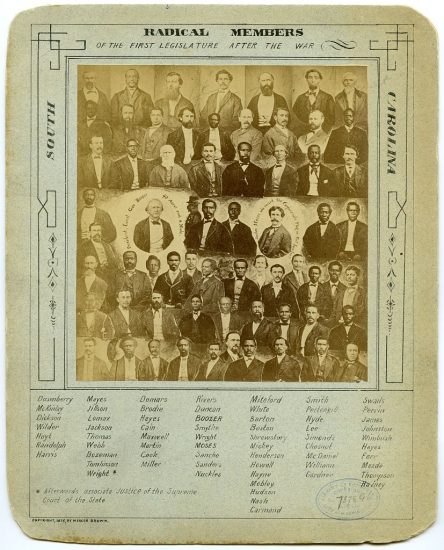

When the events of Wilmington happened at the end of Reconstruction, this town, this city on the port, this majority Black city that was relatively prosperous for African Americans, where African Americans and white people had some measure of living amongst each other, both selling goods at the port [and] competing against each other. I think that’s very important to remember the competition. They also had elected a multiracial government, a local government, which was actually making improvements for all people. And that is the backlash that ensued, because of those reasons. And, of course, racist tropes were put forward, fear mongering, disinformation campaigns, all of that. But to me, it seems that it was the promise of Reconstruction which was still happening in Wilmington in 1898 that caused such a violent backlash from the self-declared white supremacists.

Hagopian: We’ll move to the next question, but before I ask that, let’s watch a clip from the film that will help us understand why the city of Wilmington is where all these major events take place in the film.

Wilmington was the state’s largest city. As one of the ports for international travel and traffic in North Carolina, this was a very prosperous city. The railroad system drove backcountry items straight into the port in Wilmington, and then out into the rest of the world. So tar pitch and turpentine — the things that came from the forests of North Carolina — really drove some of this economy.

The sprunt cotton compress here in Wilmington. They were one of the largest exporters of cotton in the world. By this time Wilmington was one of those important centers for newly freed people to find opportunity. There was really no other major city in the South like Wilmington. First of all, it had a majority Black population of 56 percent. They have the opportunity to compete with whites for well-paying jobs for both skilled and unskilled labor.

Yes. I wanted people to get a sense of the city that I thought you did really well with that. I was hoping you could describe the political landscape in North Carolina leading up to the 1898 coup, and the significance of this fusion coalition, this fusion party between the Republican Party and the Populist Party that was challenging the Democratic Party’s dominance. So talking about why the fusion party was seen as such a threat to white supremacists, and the violent reaction they had against it.

LeRae Umfleet: I’ll take this one. Thank you so much for having me, this is great. As you were talking about history — and I’m just a history nerd in all of this — but Yoruba and her team took what I do as a history nerd and just made it so much more accessible to the general public. I’m really, really proud of being a part of that project.

As far as Wilmington and North Carolina and a fusion government, I had whole classes and very long lectures on fusion. I’m not going to do that to y’all, but essentially fusion took disaffected Democrats, which were the Populist Party, and Republican voters, who were the voters of Abraham Lincoln’s party — Black men and progressive white men — and it fused the voting power of those two blocks of voters. Because otherwise neither group would have had the voting strength to win against Democratic candidate. So in 1896, fusion successfully elected a Republican governor in Raleigh, and that was the first time we’ve had a Republican governor in North Carolina since the traditional end of Reconstruction. We can get into a whole other discussion, and y’all have done really great work about the end of Reconstruction and when that might be, but 1877 is what most historians say in North Carolina.

But I’m changing their minds slowly, and we have a Republican governor and a fusion based government in the legislature, in Raleigh and in Wilmington. That coalition of Black men and white men was very threatening to the Democratic Party, and in 1898, they set out for a long range plan to win control of the state legislature and then the governor’s office in 1900. It was a political process that turned into bullets in the street in Wilmington. Politics can turn into violence very easily through all sorts of racist tropes and stereotypical presentations of menacing Black men affecting the safety and welfare of white women and white families and things like that. So that’s the basics. And always I’ll tell folks to watch the movie.

Hagopian: Yeah, absolutely. Should we get to the next one, Yoruba?

Richen: Sure, yeah, absolutely.

Hagopian: There’s so much I want to ask you all and talk about. Newspapers play a really big role in this film, and I thought that one of the most fascinating parts of this story is how important newspapers were in shaping all these events. So, I was hoping you could talk about how the newspaper shaped public opinion and influenced events leading up to the Wilmington coup. I hope you can talk about The Daily Record, Wilmington’s Black owned paper, and how it served as a vital platform for the African American community, in contrast to white owned papers like the News and Observer. It was just shocking to see some of those articles and racist cartoons that were being used to support white supremacy.

Richen: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, that was one of the most shocking things to me, as well. How well documented and how disinformation messages were all through the white owned papers. And also how they reported on it afterwards as being started by Blacks, or now things are quelled, and these are papers like the New York Times and the Washington Post. But I will say, having done a bunch of historical films, if you look pre-1960, you’ll be shocked at how race is reported in the newspapers, generally speaking.

Then there’s an argument to be said about how it’s reported now. So this is nothing new, I guess, is what I want to bring up about the newspapers. Obviously, this was before the internet and before TV. Newspapers were how people got their information. Josephus Daniels, who was the publisher of the News and Observer, was one of the . . . Raleigh’s News and Observer was one of the architects of the coup. He had the very smart idea — since so many white people were also illiterate — to use cartoons to show this, to drum up, gin up this myth, this racist trope of the Black man raping white women and taking over government. Alex Manly’s paper, the Daily Record, was at that time one of, if not the only, daily African American newspapers in the country reporting on the Black community. Also, two ads from white businesses were in that paper, as well. Basically, Manly’s paper was used as the match to light the fuse of the coup.

What happened was a month or two before the events in November 1898, a woman named Rebecca Felton, who was the wife of a senator in Georgia, said in a speech that Black men were raping white women and that they needed to be lynched in order to stop this epidemic. So this is not something that was just confined to North Carolina. As we know, this was a racist trope that was throughout the country. But her speech was reprinted and Manly wrote a response. Manly said in his response that this is basically BS, that, in fact, especially him being the product of Black and white union, that Black men and white women very freely entered unions because white women were attracted to Black men, and that Black women had been, in fact, the ones who were raped historically, and no one said anything about that. That was incendiary.

And his response, his editorial, was used by Josephus Daniels and others as the reason. “Look what happens if we let this negro rule continue.” That was the spark. In fact, when the massacre and insurrection started to happen, one of the first things they did was to go to Manly’s, where the Record was being published. They wanted to find him [but] he had escaped. Actually he was light skinned, light enough that he could pass. That’s how he and his brother were able to escape. But they burned down the Record, and one of the few pictures that we have from the coup and massacre is that picture of the Record being burned with white men and white boys surrounding it, very reminiscent of the lynching photos that we saw at the time and thereafter.

Hagopian: Yeah, that’s such a chilling photograph of white supremacist power on display. Thank you for telling that story. I really appreciate how you don’t confine this story to just a problem in Wilmington, the way that it connects with broader structures and problems happening throughout the country.

The film includes the story of Black ministers appealing to President McKinley to protect the Black population of Wilmington. and he ultimately declined to do so. They went to him before the coup happened, before all this racist violence broke out, to ask for his support. Then you also have a powerful letter from a Black woman to President McKinley after the violent coup, still asking for support. So, I wanted to show those clips from the video and then get your comments on it.

A delegation of Black ministers went to President McKinley in Washington and warned him. The present situation in the state of North Carolina is but an act in the series of a reign of terror inaugurated in the year 1873 to wrest from the legitimate electors the state government. The present situation is a grave one, and the attitude of lawless men in the state of North Carolina will be far reaching in its effects unless it is counteracted by the strong arm of the government. The president was put in a very, very difficult position. He had been a Union officer, he was an Abolitionist, but he was going to run for reelection in 1900, and he needed the white vote as much or more than he needed the Black vote. And McKinley absolutely refused to send federal troops in. The attorney general made the point, “Well, we can’t send any troops in because Governor Russell has to request the troops time.” He’s told, “You’re no longer welcomed here in Wilmington, North Carolina.”

November 13, 1898, William McKinley, President of the United States of America. Honorable Sir, A negro woman of this city appeals to you from the depths of my heart to do something on the negroes behalf. I call on you, the head of the American nation, to help these humble subjects. We are loyal, we go when duty calls us, and we die like rats in a trap, with no place to seek redress or to go with our grievances. Why do you forsake the negro who is not to blame for being here? How can the negroes sing “My country ‘tis of thee”? Today we are mourners in a strange land, with no protection near. God help us! Can I say my name and live? But every word of this is true. Yours in much distress, Wilmington, North Carolina, Anonymous woman.

Oh, what a powerful part! I wanted to ask you, how do you interpret the federal government’s role, or lack thereof, in these events? What does it say about our country as a whole, not just the South or North Carolina?

Umfleet: Well, from McKinley’s perspective, he didn’t have the authority to step in because, as it points out in the film, Governor Russell didn’t ask for his help. Additionally, the folks who planned and carried out the violence in the coup also did so knowing that there were certain things they should not do, and one of those things was to interfere with the jobs and the safety of federal employees, because the only precedent since the end of the Civil War for the president to send troops into an area was if federal employees were affected and their ability to do their job was impacted. So federal employees were protected if they were Black, and they were not molested in any way, shape, or form.

McKinley had undercover agents in Wilmington sending him telegrams, letting him know what was going on and the progress of the election beforehand and then after the violence took place. It was very easy, “by the way, we have no authority to send troops in” response from the federal government. Then the folks who were running for election and who were the federal election for the Congress, they tried to say that the election was coerced. They had no ground to stand on, because no one in Washington, D.C. was going to take that on. Many leading white men in North Carolina had written to the president and to others to say, “If you send federal troops to North Carolina, you will have another Civil War on your hands.” So there were many reasons why McKinley didn’t step in. He had plenty of knowledge of what was going on and the negative effects on the city and the people of Wilmington.

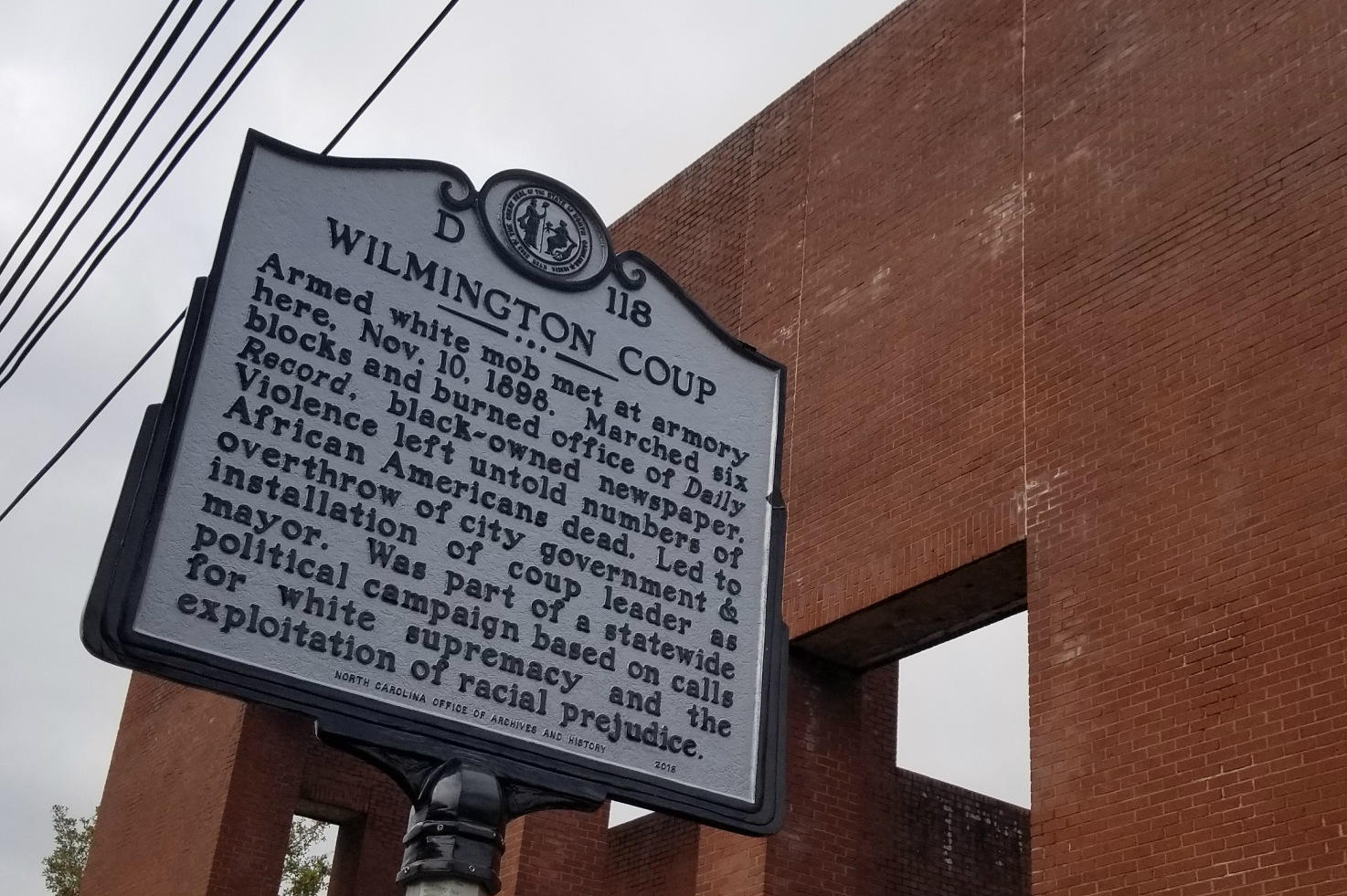

Hagopian: Yeah, thank you for that. That’s such an important context to understand how this was allowed to happen. Increasing numbers of people, although still far too few, know the story of the Tulsa Massacre. I think the 2020 Uprising brought out the history of the Tulsa Massacre for many people, the attack on what was called Black Wall Street, burning it to the ground. One of the most prosperous communities in the country, but still very few know about the similar events on November 10, 1898, in Wilmington that were organized by a group that called itself the Secret Nine. I wanted to show a short clip from your documentary to show us what happened that day of the coup.

By mid-afternoon on November 10th the shooting had started to die down because so many people had fled. Waddell and the other leaders of the conspiracy turned to actually taking over the city government. They met at Thalian Hall, and all these gunmen from the streets course in there in just a high state of rage and anticipation. They call the sitting government in, the mayor, the police chief, the alderman, and at gunpoint they tell them that there is a white revolution, their jobs no longer exist, and they have to resign. Then the mob leaders installed Waddell as mayor. They replaced the police chief with a former Confederate officer following the rule of law that said if a member of the Board of Aldermen resigns his seat the existing Board then votes to fill the vacancy. Waddell conveniently had a list of pre-approved white supremacy candidates for the Board of Alderman seats for each precinct. And one by one, members of the Board of Aldermen resigned their seats. And one by one, new people were put in place. Alderman Keith and C. D. Morrill having tendered their resignations as members of the Board from the 3rd Ward, Hugh MacRae and J. Allen Taylor were elected aldermen in their stead. They were sworn in by the mayor and took their seats.

This is a transition of government under duress. A definition of a coup d’etat is an armed overthrow of a legally elected government, which is what happened on this day in Wilmington. It makes it really palpable. That’s how he did that, or they did that.

Banished by whites, leaders of the negro element are forced to leave Wilmington, North Carolina. Men of both races who are held responsible for inciting the negroes were forced to leave the city today. These men are regarded as a menace to the peace of the community. After Waddell and the white supremacists have taken over the municipal government then it is okay. We can’t have these rabble rousers among us. So basically, they ordered the Black leadership to leave. Many of these Black individuals and their white allies received visits from white supremacists, and they were escorted to the train station, essentially saying, “You are banished from ever living in Wilmington again.”

Yeah, so chilling! Can you walk us through what happened that day? The intense violence, the burning of the Daily Record, the exile of Black citizens, and really what you want viewers to feel and to understand about these scenes in the documentary?

Richen: Rae, you want to take them through the days, and then I’ll talk about what I want them to feel?

Umfleet: Okay. Election day was November 8, 1898, and through a whole series of efforts all Republican candidates, for the most part fusion candidates, were removed from the ballot. And through voter fraud, intimidation, ballot stuffing, and all the things Democratic candidates were elected across the board.

November 9, the day after the election. The city of Wilmington is still on edge. I mean, they’ve been on edge with patrols, and fears of Black retaliation, and all these things throughout the whole months of October and November. The white community comes together [and] they pass a resolution called the White Declaration of Independence. Basically, it said, “We will never be ruled again by men of African origin. And we want these things to happen. We want Alex Manly to leave [and] stop printing his paper. We want the mayor and the Board of Aldermen to resign. We want Blacks fired, whites hired; Black wages lower, white wages higher; those kinds of things.

Then, after that resolution was passed on the 9th, the morning of the 10th came a response from a group of Black men called the Committee of Colored Citizens. They were business leaders, civic leaders, community leaders, ministers, things like that. They were supposed to have their response from a white leader called Waddell the next morning. The official response didn’t come, but Waddell had been informed of what they were going to say, which was, “We’re going to do everything we can. We don’t have the authority to make him stop printing his press, but in the interest of peace we’ll do what we can.”

Then the crowd gathers and starts to grow out on Market Street. Waddell marches the men down to where the printing press building was. Manly was not there. As Yoruba said, he was warned and he had gotten out of town. They knock on the building, they break in, the building catches on fire, they allow it to burn until it’s not salvageable, and then they allow a Black firefighting unit to come in to put the fire out. Waddell then tells the crowd, “You’ve done your duty. Go home.” But human nature being what it is, those men had adrenaline pumping and they couldn’t just put down their guns and go home. They wanted to do more, plus they had been pumped with whiskey by the white supremacists.

So some men got on a trolley, went to the other end of town where they lived next to their Black victims, and there was firing. Shooting broke out at the corner of 4th and Harnett. The first few Black men were killed there at that intersection about 11 o’clock in the morning, and from there it’s a running firefight. If you’re a Black man, you literally had a target on your back. and there were almost skirmishes throughout the city, in the north end of town. In the center part of the north end of town, it’s a mixed race neighborhood, whites and Blacks living next to each other. The further you go out to the fringes the more so you see mainly Black communities. And these white patrols are running through this whole area. They swear that people started shooting at them.

There are firing lines, the Gatling gun is used, and we really don’t know the total number of people who were murdered that day. I’m a historian, so I need the documentation. I played attorney, looking at circumstantial evidence to figure out how many people I could identify as being murdered that day. Forty to 60 is the solid number; up to 200 is the number that I’ve seen that I could conceivably say 200 people died that day. There were about 20,000 people in the city at the time.

And from there the families flee Wilmington. The Black families go in all directions. Some spend the night in the swamps, some never return, others return just long enough to get their belongings and leave. Wilmington then moves into a scenario where Blacks are put into second class status — lower pay, lower wages, forced out of the central business district. Entrepreneurship dies and day laborers are left with lower wages than they had before November 10, 1898.

Hagopian: Thank you.

Richen: And then the coup happens. I also just want to say one thing because you mentioned Tulsa and 2020, how that brought a lot more awareness. First off, it’s important to know that racial terrorism happened throughout the country. This was not just Tulsa, it wasn’t just Wilmington, and most of those are not known and have been covered up purposefully.

Also, one of the things that struck me — and this was maybe right before I started or as I was working on the film, because it took us about three and a half years to make it — in 2019 there were a lot of commemorations of Tulsa. There were podcasts, there were documentaries, and I watched and I listened. And I never heard one white descendant of the perpetrators being interviewed. In Tulsa they talked about the wealth that was stolen and put in the houses of white people. So those white kids and those white grandkids saw that loot that was taken. I thought it was so important to have the descendants of both Black and white, the Black victims and the white perpetrators, to understand what the stories were that they were told or weren’t told. How were they grappling with their history?

What we see in the film, as we see some of these white descendants and Black descendants coming together to grapple with it or grappling with it on screen, and I just think that is so . . . . We’re never going to move past, we’re never going to really deal with our history of racism in this country, and racial terror and structural racism and all of that, until we have white people coming to the table around this issue. So my co-director and I, really that was one of the things that we knew from the beginning that we wanted to have included in the film, and what we want.

To your question of what we want people to take away, first off, obviously we can’t tell everything in one film. I hope people will be inspired and curious enough to find out more about Reconstruction, more about racial terror, more about some of these figures that we highlight in the film, and also to understand that there are echoes of a lot of things — echoes that we have today, misinformation and disinformation, racial tropes and stereotypes — that these are things because we’ve never really confronted them and dealt with them. There are echoes that we are seeing today.

Hagopian: Absolutely. It’s so powerful how you have descendants of both the victims and the perpetrators of this event throughout the film. I want to get to some more of those questions after the breakout, especially because my own family recently found out where our ancestors had been enslaved, and I recently had a chance to get lunch with the family that had owned our family.

Richen: Oh, wow!

Hagopian: I can’t even figure out how to describe it. But watching your film really helped me process that experience for myself, so I wanted to thank you for that.

[breakout rooms]

Hagopian: All right. Welcome back, everybody! So, we’ve heard from dozens of teachers about why they teach Reconstruction. Yoruba, I know that you had some resources and ideas also for ways to bring this history alive.

Richen: Yeah, I just wanted to mention that our partners, PBS North Carolina, they’re the ones who conceived of this film and this project. They knew they wanted to make a feature documentary about the events of Wilmington and they reached out to my co-director and I, Brad Lichtenstein, because of other work that we’ve made dealing with similar themes. And we enthusiastically signed on. But we were also really excited because from the beginning educational impact was going to be a big part of the work that they wanted this film to do. The broadcast is really only the beginning. We’re working with Working Films, which is a Wilmington based impact organization that works with films on social change. We’re working with Picture Motion to get the film out there, to have screenings and talk backs with descendants and scholars.

Since these are [primarily] teachers on this Zoom [call], and educators, I just want to tell you a little bit more about what some of the educational materials and resources will be. There are going to be two interactive lesson plans — one around the events of the 1898 coup and massacre, and one on the events leading up to 1898, covering Reconstruction and the thriving Black middle class in Wilmington. There are going to be five screenings of the film targeted to educators, featuring a screening of the film and a panel of educators, providing insights into how to teach this hard history. Virtual workshops and webinars, teacher trainings, a community of practice which will be an internet-based forum for teachers to discuss and exchange ideas related to teaching the story of Wilmington, 1898.

Also, GBH is creating a lesson plan on the role of the press in the Wilmington coup that examines the roles played by newspapers in 1898. If you go to the website now there are also articles already on the site today. I believe earlier today they posted an article called How to Cover Up a Coup that looks at the role of textbooks in covering up 1898. So, I just wanted to make everybody aware that those are educational materials that will be forthcoming.

Hagopian: Excellent. Thank you so much. Well, I have a couple more questions I want to get to, and I’m also seeing the chat is alive because so many people love their small group breakouts. I see a lot of great shout outs from all these different groups and really interesting conversations. I’m excited about the new lens that you’re going to help provide students with this history.

But there’s a powerful portion of the film that interviews people who grew up in Wilmington, North Carolina, about what they did or what they did not learn about the coup. So I wanted to have us watch a clip, and then I’d love your thoughts on how this history should be taught to students today.

The ways that the history appears in things like textbooks is very revealing in terms of how they want to be seen and how they want this event remembered by any readers, Black or white. So there is a strategic campaign of telling a very distorted version of this history. There were many negro officeholders in the eastern part of the state, some of whom were poorly fitted for their task. This naturally aroused ill feeling between the races. The mass of negroes became poor citizens to keep their vote. The carpetbaggers and scalawags allowed them to do very much as they pleased.

The white people of the South were no longer safe. A number of Blacks were jailed for starting a riot and a new white administration took over Wilmington’s government. The perpetrators, during their lifetimes, bragged openly about it. But once that generation died out, people realized that wow, this is a real stain on Wilmington. So it was buried. It just disappeared as if it had never happened.

Both sides of my family are 8th generation North Carolinians. I had never heard of the Wilmington racial massacre until I was in my late thirties as a North Carolina native. I took several courses on North Carolina history throughout my middle school and high school career and I never recall hearing about the Wilmington Insurrection as a part of any social studies or history class that I took. I didn’t know about it, like everybody else in Wilmington for a very long time. When I was growing up here in high school and even into college, I was drinking the Kool-aid. I learned all this about my great grandfather in 2018, and it was just a physical blow to my body because it was such a departure from everything I’d been told about my family and everything I had believed. None of this.

I saw some people in the chat talking about being from Tulsa and students there not learning anything about the Tulsa Massacre. Your thoughts about why this history is not very common in our textbooks, and how it should be taught?

Richen: Well, I feel like you guys are the experts in how it should be taught. First of all, I think understanding the facts about what happened, that’s not disputable. That’s not political; those are the facts on the ground. And it was well documented. It was. There’s so many primary texts that document it, so I think it has to be taught as history. There’s also other tools that can help. I mean, we also show in the film that Birth of a Nation was based on a book by a Wilmington writer. It’s kind of like the cinematic version of what they were trying to do, and did, in terms of talking about bad government [and] raping white women.

There are other tools, too, I think, that can be helpful for understanding what happened in Wilmington. The descendants are very much wanting to bring this history, and they are going to be part of our impact campaign. Folks can reach out to them, to educators, to bring them into class. I think it’s so important to see the real life consequences and hear from people whose families were directly impacted as well. I think that can be interesting [and] fascinating for students, and make it real.

Hagopian: Yeah, no doubt. I think that’s crucial to make it real, to connect it to what’s going on today. I think that one of the most powerful parts of this film is that it incorporates interviews with descendants of both the coup’s perpetrators and its victims. I was hoping you could expand more about how you connected with those individuals. What did their stories bring to the project? Were there any reactions or perspectives that surprised you?

Richen: Yeah, I talked about it a little bit before, because it is so important. It was so important to our process and so important to the film. As I said, we knew from the beginning we wanted to bring those voices in, and we were lucky in coming to the table as a national group that deals with racial issues around the country. In Wilmington it is focused on Wilmington, and descendants of victims had been meeting together for some time before we started. One was the descendants of perpetrator Lucy McCauley, who’s in the film. We found out about this group [and] we connected with them. We started attending their meetings and meeting them and slowly began a relationship with these descendants.

When we started filming, we also did some trust building with them as well. That was needed. Neither Brad nor I are from Wilmington. All kinds of power dynamics can come in and we wanted to make sure that the descendants felt comfortable, that they wanted to work with us, if they had questions that could be answered. Lucy was the only white descendant that had been a part of the group, but she had connections to other white descendants who she thought might be interested. We also did our own work. We found some who are featured in the film, like Frank Daniels, the descendant of Josephus Daniels. Ann Keenan and Ann Russell. So that was great. Then we also had people who did not want to take part, who thought they might want to take part and then decided that they didn’t want to take part, and others who said, flat out, “No”. So it was definitely a process, but it was something that we were committed to.

Hagopian: It just transformed the storytelling. You brought this history from 1898 to life. I just want to congratulate you both for bringing us this story, and thank you so much for your time this evening, and sharing this story with all these educators, that we can bring it to thousands of students across the country.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect, please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Resources

Here are many of the lessons, books, and other resources recommended by the presenters and participants:

Lessons

|

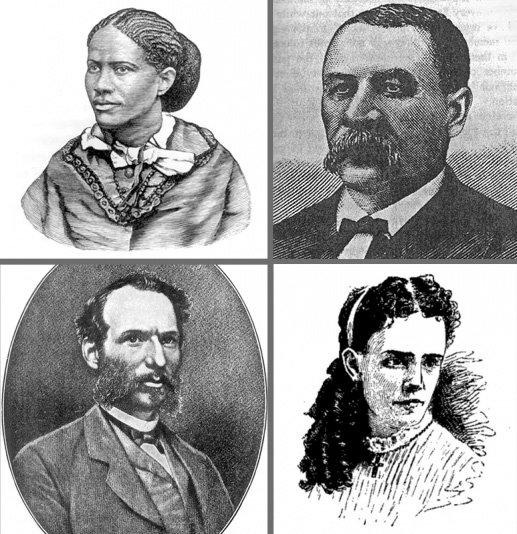

Reconstructing the South: A Role Play by Bill Bigelow Reconstructing the South: What Really Happened by Mimi Eisen and Ursula Wolfe-Rocca When the Impossible Suddenly Became Possible: A Reconstruction Mixer by Adam Sanchez and Nqobile Mthethwa Who Killed Reconstruction? A Trial Role Play by Adam Sanchez Find more recommended lessons at our Teach Reconstruction campaign page. |

Books

|

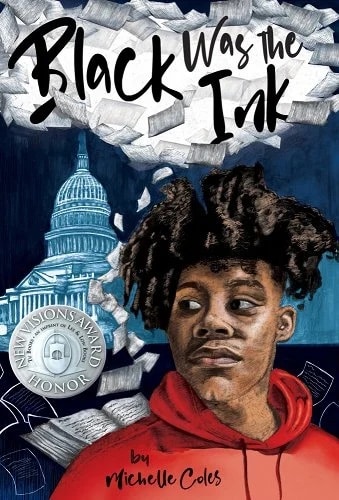

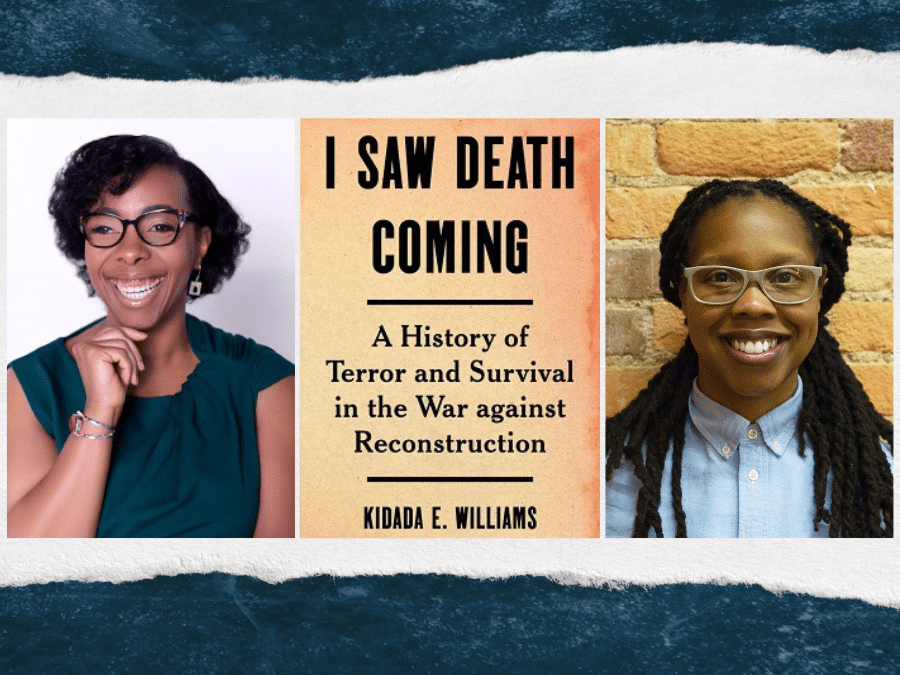

A Day of Blood: The 1898 Wilmington Race Riot by LeRae Umfleet (North Carolina Division of Archives & History) A Moment in the Sun by John Sayles (McSweeney’s) Black Was the Ink by Michelle Coles (Tu Books) Cape Fear Rising by Philip Gerard (Blair) Crow by Barbara Wright (Yearling Books) I Saw Death Coming: A History of Terror and Survival in the War Against Reconstruction by Kidada Williams (Bloomsbury Publishing) Find more recommended books for K–12 and adults on Reconstruction at Social Justice Books. |

Articles

|

Five Ways Textbooks Lie About Reconstruction by Mimi Eisen (an addendum to the Zinn Education Project report, Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle) How to Cover up a Coup by Kirstin Butler (PBS) The Lost History of an American Coup D’État by Adrienne LaFrance and Vann R. Newkirk II (The Atlantic) |

Documentaries and Podcasts

|

American Coup: Wilmington 1898 (PBS) Echoes of a Coup (Scene on Radio) Reconstruction (Slate) Teaching Hard History: Reconstruction 101: Progress and Backlash (Learning for Justice) |

This Day In History

The dates below come from our This Day in People’s History collection, which contains hundreds of entries all searchable by date, state, theme, and keywords.

|

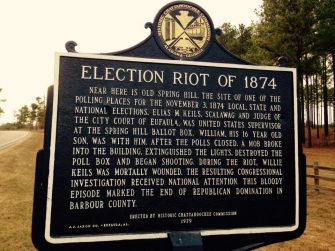

Jan. 14, 1868: South Carolina Constitutional Convention Aug. 2, 1869: First “Redeemer” Government Established in Tennessee Dec. 12, 1870: Joseph H. Rainey First African-American in U.S. House of Reps July 7, 1871: Testimony at Klan Hearings by Elias Thomson April 13, 1873: Colfax Massacre Jan. 6, 1874: Robert B. Elliott Spoke of Need for Civil Rights Act Nov. 3, 1874: White League Attacks Black Voters April 14, 1875: Frances Harper on Grassroots Organizing During Reconstruction Oct. 22, 1883: Frederick Douglass Denounces Supreme Court Ruling Nov. 23, 1887: Thibodaux Massacre Nov. 1, 1890: Mississippi Constitution Nov. 10, 1898: Wilmington Massacre May 31, 1921: Tulsa Massacre |

Participant Reflections

With more than 185 attendees present, the conversation and chat was lively, engaging, and full of history, teaching ideas, and more. Polls showed participants included 40 percent K–12 teachers, 10 percent teacher educators, 9 percent historians, 7 percent K–12 students, and more.

Here are more comments that participants shared in their end-of-session evaluation:

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

The facts about the Wilmington coup. I knew nothing beforehand. And that there is a magnificent film about it.

How much of our history is left untold and oversimplified in order to fit the narrative that benefits those in power.

The fact that media and news and textbooks erase history and bend the story.

How quickly and easily democracy was overturned.

Tighter connections between the Reconstruction era and the politics and ideas still being fought today.

How the Wilmington coup was not only a strategic attempt to wipe out the gains of African Americans, but also how the press was involved.

In the film, the coming together of both of the descendants of the victims and the perpetrators in Wilmington was powerful. You rarely hear from the white descendants of the perpetrators.

How we can use local history to find stories with cultural relevance for our students.

Thinking about how every single civics class in the U.S. should be teaching about the Wilmington coup.

The most important thing to me is the parallel between what happened in Wilmington and what is happening today. It’s shocking how little I was taught growing up.

U.S. history is a series of connected events that are poorly covered in history, so we don’t learn about patterns and fail to see them. And this is intentional.

What will you do with what you learned?

This will definitely be a focus of study — especially as a challenge to the predominant narrative that Reconstruction ends with the election of 1876 and the removal of troops in 1877.

I would love to be able to use this in my economics class, as I teach Black history through a lens that helps my students understand the connection between race and economics in this country.

I will have my students watch this documentary in chunks! I already teach Reconstruction in depth and am excited to integrate this into my practice!

As a librarian, making sure the resources are in the library and classrooms so teachers and students have access to them.

Incorporate it into my Reconstruction unit and connect it to modern voter suppression, racist rhetoric, and redlining/sundown towns.

I will use the discussion and teaching perspective shared in the breakout session to inform the professional development we offer.

Share this as another example of the history of the racial wealth gap in the U.S.

I am going to engage my students in on-demand research around the coup as we explore the idea of “Americanism” this school year.

I’ll continue to use this incident as a case study in racism and how the U.S. government was intentional about keeping the African American perspective hidden.

I coach other teachers so will be sharing the film and resources and planting seeds of lessons.

How was the format for the class?

I love everything about this session. I loved hearing about the film and what inspired it, and I also enjoyed being in the breakout rooms sharing.

The breakout room was a highlight!

I loved the back and forth in the comments, and the smaller groups allowed us to get more involved.

I enjoyed all aspects of this course and the format. The breakout sessions were beneficial and insightful.

The breakout room was awesome. We got to unpack strategies to take back to the classroom. Thank you!

Nice flow with curated content and excellent contribution from the experts.

I’ve been attending since 2020. These classes run like a well-oiled machine.

Event Recording

Coming soon.

Presenters

Yoruba Richen is the founding director of the documentary program at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York. She is an award-winning documentary filmmaker. Her film The Rebellious Life of Mrs Rosa Parks premiered at Tribeca Film Festival and won a Peabody Award. The Zinn Education Project developed lessons to accompany the film. Her other films include The Cost of Inheritance and The Killing of Breonna Taylor.

LeRae Umfleet works with the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources to develop outreach and specialty programming projects on behalf of the Secretary’s office. After three years of research and writing, LeRae produced a legislative report for the 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Commission in 2005. In 2009, the report was published as a book, A Day of Blood: The 1898 Wilmington Race Riot. LeRae consistently seeks to broaden our collective knowledge of the multitude of tragedies that occurred in November, 1898.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing, author of Teach Truth: The Struggle for Antiracist Education, and serves on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn