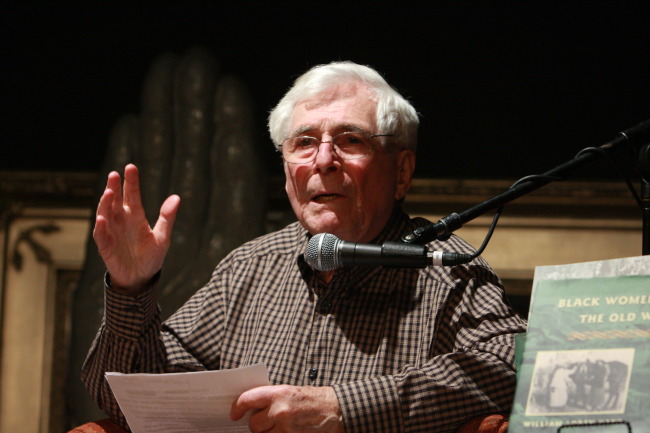

We are saddened to share that William Loren Katz passed away on October 25, 2019. Read “William Loren Katz, Historian of African-Americans, Dies at 92” in the New York Times, Nov. 21, 2019.

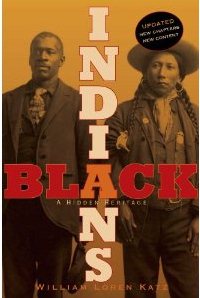

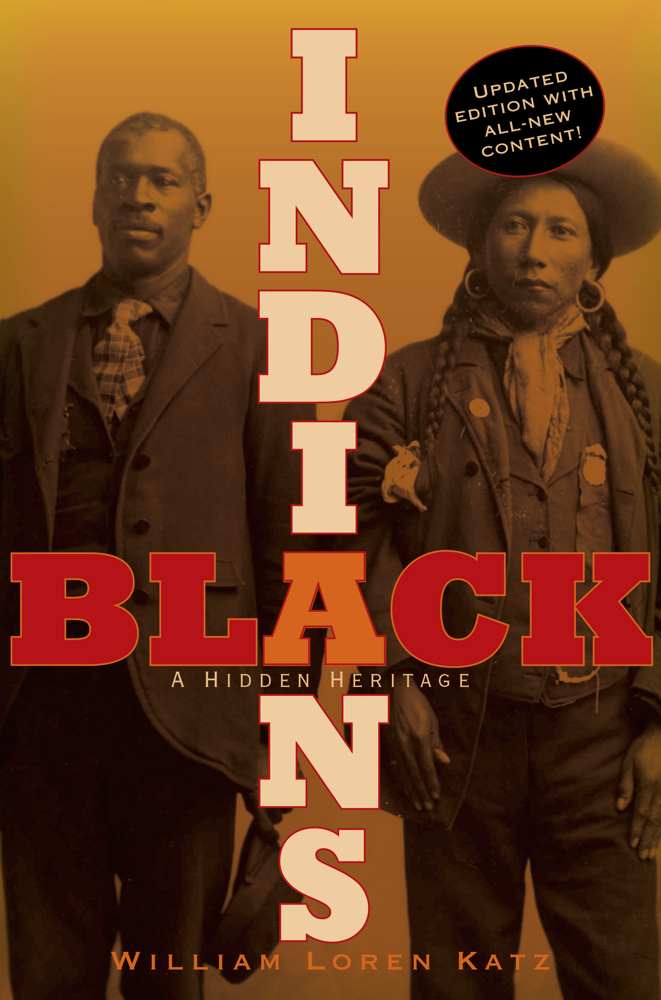

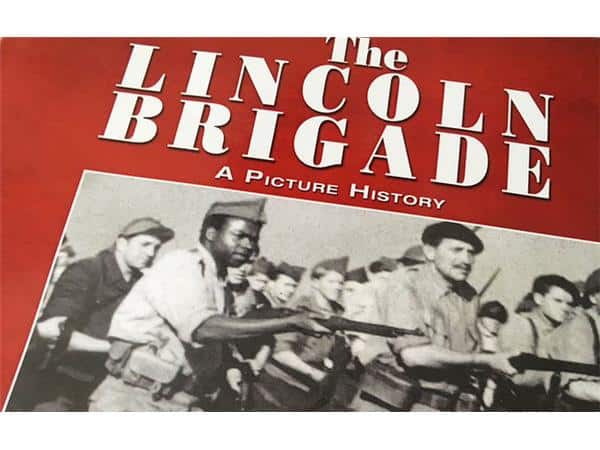

For nearly 70 years, William Loren Katz was a teacher and author of people’s history books for middle and high school students. Katz wrote 40 books on African American and American Indian history, including Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage and The Lincoln Brigade: A Picture History. His work earned widespread praise from noted scholars including Howard Zinn, John Hope Franklin, Henry Louis Gates Jr., Alice Walker, Betty Shabazz, Ralph Bunche, James M. McPherson, and others.

In the fall of 2014, the Zinn Education Project interviewed William Katz for our series of profiles of historians who document untold history, particularly for young audiences. Katz described his experiences growing up during the Great Depression and teaching during the McCarthy era. He also paid homage to his father Ben Katz, a cultural and political activist.

Childhood

Born in 1927 when Calvin Coolidge was president, I vividly remember the Great Depression. Both my parents had to work, so I was given a key for our apartment. I had an exciting life with many friends on West 13th Street in Manhattan. We played marbles and punch ball and collected war and baseball cards. On my 10th birthday, I got a large bag of cherries and three comic books. Standing in the lunch line at PS 41 in Manhattan, I heard a little girl in front of me tell her friend that her parents gave her a dime on her birthday.

My mother died very early in my life. My stepmother became an editor at Parents magazine; she was very good at editorial work.

One of the most inspiring aspects of Katz’s life story is the powerful influence of his father, Ben Katz, on his son’s future activism. In the early 1930s, his father was drawn more publicly into politics through his support of New Dealer Fiorello La Guardia’s mayoral campaign. Ben’s work life also shaped his political views.

My father had a job as a commercial art director for an advertising agency. He hated the work because it amounted to selling people products they didn’t need. He started to read on his own, although he dropped out of high school, and then fell in love with jazz music. He soon had a sizable collection of records including Bessie Smith, Louie Armstrong, and King Oliver. The music forced him to ask more questions about history. My father began asking, “Where did this music come from?” And the answer was that it came from people of African descent who are completely unmentioned. I was one of the few white kids in the world who was put to sleep listening to music from Bessie Smith and Louie Armstrong and woke up surrounded by books by W. E. B. Du Bois and Frederick Douglass.

When asked how his father’s political consciousness developed, Katz explained:

My father grew up in a comfortable neighborhood in Brooklyn, Bensonhurst, and his father owned a clothing factory. By 1919 he dropped out of high school. There were lots of strikes in 1919, and his father ordered him to run the building elevator when the other workers went on strike. He hated that, he sympathized with the workers. He also saw a lot of factory owners who paid their workers low wages but, as Zionists, contributed money to buy trees to plant in Palestine. He resented the hypocrisy of that.

Katz’s early education emphasized obedience to the government and he reflected on the power of those symbols and rituals of patriotism.

At PS 41 the curriculum was patriotic and dull. We read the textbook, as a matter of fact; we read it aloud in class. We recited the Pledge of Allegiance every morning. I remember a time when we sang the Star Spangled Banner; I actually got a tingle in me. I can’t explain it, it was psychological, and it made you want to swear your loyalty to the government, ready to do what is asked of you.

Katz’s father’s political activism acted as a counterbalance to the school curriculum.

My father took me to union meetings and demonstrations. I remember marching in the 1937 May Day parade and I remember signs there, like “Free the Scottsboro Boys!” and signs against Hitler and Mussolini.

This was Katz’s first public protest. His father took photos (see below) and filmed (with 8mm) the protest. Katz donated the film to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture Archives.

His father also introduced him to some of the great African American artists of the time.

Before WWII, my father’s activism drifted into the areas of defense of civil rights and black self-determination. He became a founding member of the Committee for the Negro in the Arts in the late 1940s with such notables as Charles White, Ernest Crichlow, Harry Belafonte, Sidney Poitier, Alice Childress, and so on. He and Walter Christmas co-authored “Lift Every Voice Poetry Production,” a play on African American history that was performed in the basement of the Schomburg Library.

(L-R) Walter Christmas, Ruth Jett, Charles White, Janet Collins, Frank Silvera, Viola Scott, and Ernest Crichlow.

Growing up during Jim Crow, Katz had the good fortune of living in a desegregated community.

It was a mixed neighborhood, West 13th Street and 8th Avenue, the kids came from all over, they were mixed racially. I remember Harry and Emily were from the West Indies, my good friend Martin Azarian was Armenian, from whom I first learned about the Armenian Holocaust by the Turks that happened around the time of WWI. I also remember our discussions on the street about whether major league baseball should hire black players. I remember some of the silly arguments I heard: “Oh they aren’t good enough” or “They are too good.” My position was a minority view, which was, of course, they should be allowed to play.

The neighborhood pool was the first place he met the subject of one of his future books, The Lincoln Brigade.

I was 10 years old and it was the summertime. I went to the LeRoy Street public swimming pool and on the other side of the pool I see my father’s friend Ernie Crichlow, whom I had met in our apartment many times. He introduced me to his friend, Joe Taylor. When I told my father that I met Ernie and Joe Taylor, he asked, “Do you know who Joe Taylor is?” I said no.

He explained that Joe Taylor was one of 90 African Americans who volunteered in the racially integrated Abraham Lincoln Brigade that went to Spain to fight fascism. Joe was a black man and actually he had to swim the Ebro River to escape the Franco forces. When he got to the other side, the Spanish people surrounded him thinking he was one of the Moors Franco conscripted. He explained that he was an American and was rescued. This was the first time I ever met a veteran of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. Many years later I wrote a book on the Brigade and its 2,800 American volunteers. It was an inspiring example of people coming together across the flaming fires of race to unite against the kind of oppression Hitler was trying to impose on the world.

High School

In 1941, Katz attended a new experimental high school in Greenwich Village started by progressive educator Elizabeth Irwin, who ran the Little Red School House.

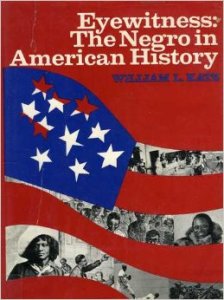

It was there that I was first able to express my knowledge and love of African American history and music. My senior year I wrote a 200-page history of jazz. The first three chapters on slavery were very much like my first book on Black history, Eyewitness. I was in the high school’s first graduating class in 1945.

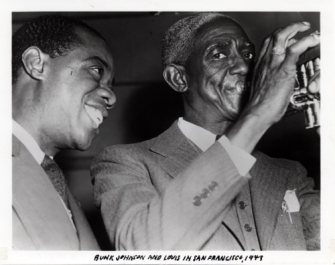

Louis Armstrong and Bunk Johnson, 1943.

Thanks to his father, Katz’s experiences inside this new school mirrored his experiences outside of it.

By then Dad had taken me to the Schomburg Library, and to hear Billie Holiday, and to jazz concerts at Town Hall he organized to raise money for the integrated United Negro and Allied War Veterans of America. I got to meet my jazz heroes like Sidney Bechet, James P. Johnson, the father of stride piano, and the niece of Bessie Smith named Ruby Walker, in our living room. This had a powerful impact on me.

Later I was introduced to Louis Armstrong and Bunk Johnson, the legendary New Orleans jazzman who helped teach Armstrong the cornet.

In the Navy

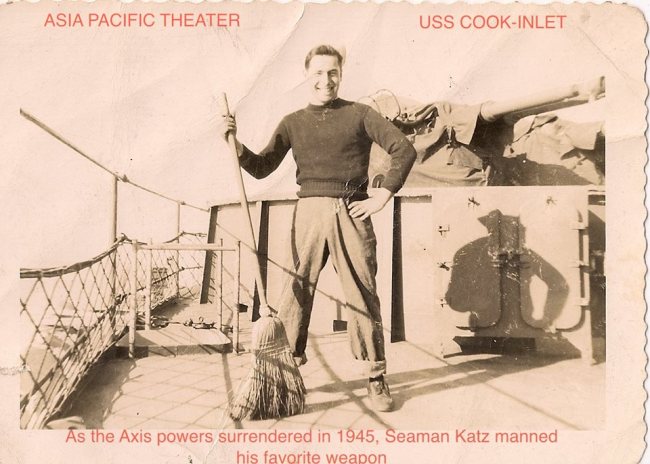

Katz served in the U.S. Navy during the last 13 months of the war. He recalls a day’s leave he spent in Japan where he saw people begging for money, and how different that image was from the representations of Japanese back in the U.S. Another influential experience was when he got on the wrong side of the captain of his ship, the USS Cook Inlet, who he describes as “a Southerner bigot who drank a lot.” The captain didn’t like Katz and as a punishment, changed his battle station to the bowels of the ship.

William Katz in the Navy.

When the alarm went off I raced to my new battle station and found myself sitting with six black sailors I had never seen on the ship before. They were mess mates because that is all the Navy offered black men. We smiled and chatted and talked and joked. We all figured out that the captain wanted to punish me but this wasn’t a punishment for me! Quite the opposite. But I had no idea these men were even on the ship. And I thought, “How the hell did I not know?” There were two good reasons: The captain kept them segregated. Secondly, I reasoned, “If I was them at sea, I wouldn’t want to go out on deck.”

It was “on deck” where Katz and some other 18-year-old Northern white sailors were surrounded by Southern white shipmates who described horrific lynchings of African Americans.

University Student

As a GI bill student at Syracuse University, Katz collided head-on with the curriculum.

It was dull and useless. The teachers were boring, their knowledge of history traditional and thin. One professor maligned the Molly Maguires as being dangerous thugs and rejoiced at their hanging. He didn’t even tell us the story, just that they were horrible people. He made me want to learn more about them, so I wrote a paper. They were oppressed Irish American coal miners who formed a union against Pennsylvania mine owners, only to be framed by the bosses and the state government.

It was dull and useless. The teachers were boring, their knowledge of history traditional and thin. One professor maligned the Molly Maguires as being dangerous thugs and rejoiced at their hanging. He didn’t even tell us the story, just that they were horrible people. He made me want to learn more about them, so I wrote a paper. They were oppressed Irish American coal miners who formed a union against Pennsylvania mine owners, only to be framed by the bosses and the state government.

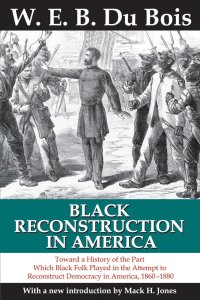

I had other troubling experiences at Syracuse University, about as far north as you can get. It was 1950 and I was taking a class on the Civil War and Reconstruction. I read W. E. B. Du Bois’ Black Reconstruction, and wrote a paper on it that my professor handed back with one word written at the top: NUTS! Now, if you think that is bad, listen to the exam question. We were given five questions to answer, one of which was: “Justify the actions of the Ku Klux Klan.” This kind of mind-numbing nonsense passed off as history led me to rebel and do my own research.

Like their professors, many of Katz’s classmates sought to maintain the status quo.

I remember the 1948 election campaign. I volunteered in the Young Progressives supporting Henry Wallace and Senator Glen Taylor. We brought Senator Taylor to the university but he was not allowed to speak on campus. So he spoke at a park along fraternity row. First, someone cut the speaker wires and a student had to hold them together. Then a fraternity house unfurled a huge Nazi flag.

Yet these same experiences put him in contact with people who thought differently.

While I was a student at Syracuse University and a Young Progressive I met Woody Guthrie in 1947, and Pete Seeger a couple years later. I met people who shared my interest in history.

Woody Guthrie plays his guitar and Pete Seeger accompanies on banjo; music journalist Dan Burley sits at left. Source: Leonard Rosenberg.

Classroom Teacher

After attending the NYU School of Education and receiving his master’s degree in 1952, he postponed his teaching career to avoid the height of McCarthy hysteria, the state-sponsored witch hunt for Communists and progressives during the 1950s led by U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin. But, he could not resist his calling and began teaching in 1955 at Junior High School 52 in Inwood, Upper Manhattan, despite being forced to sign a loyalty oath.

I think there were four or five questions like, “Would you use your classroom to advocate for the forcible overthrow of the U.S. government?” I was called in and asked a couple of questions because I had given two incorrect answers. I found the questions so wordy, convoluted, and confusing that I, in fact, answered yes. The clerks were very nice about it and let me change my answers to those required. They helped me fill it in the proper way (laughing).

Katz describes the way the Board of Education dealt with other loyalty issues.

At one point the board called me in to question me about my loyalty. I taught briefly in a Jewish parochial school and another teacher reported me for discussing the [Julius and Ethel] Rosenberg case with my class and raising questions about whether they should be executed. I was called into a rather dark room with a long table with me at the one end and three questioners at the other end.

In a procedure hard to fathom they asked me if I was loyal. I said, “What do you mean loyal? I joined the U.S. Navy, I volunteered for WWII. How do I prove it?” One of the interrogators asked, “Do you have any U.S. war bonds?” It just so happened that I owned $175 in war bonds. Hearing this they said, “OK,” and I was off the hook. That was the level of stupidity in the McCarthy era.

His war bonds, rather than the quality of his teaching, secured his job in the eyes of the school administrators.

When I began teaching in 1955, I learned to close my door. A teacher in the room above me, a very conservative guy, asked his class, “The president gets $75,000 a year. Do you think that is too much?” The principal pulled him out of the classroom and told him not to ask questions like that. That was McCarthyism in the public schools.

These teaching experiences made Katz realize that he wanted to create more accurate and inclusive teaching materials.

In American history classes, African Americans were completely absent, or were portrayed as happy under slavery and bewildered by freedom. I began bootlegging material into the classroom, often eyewitness accounts that revealed the role of black people in American history. It strayed from the curriculum. It challenged textbooks and what they had learned before.

One white parent objected to my using an Abraham Lincoln quote showing his racist thinking. But surprisingly, I found my students, both black and white, liked this content showing how enslaved people resisted and had some white allies were moved by their conscience. These lessons showed the students how they could resist injustice and shape their own lives.

Research and Writing

Katz’s curricular writing took off while teaching at the integrated Woodlands High School, in Westchester, New York.

It was a new, racially integrated high school and it had been integrated after WWII when white people began moving into the lower-rent black neighborhood. Here I was allowed to develop my materials that grew into my books. I had the wonderful experience of having students evaluate these historical documents and pictures. My first book, Eyewitness: The Negro in American History, was really shaped by my students. I am still in touch with some of them.

It was a new, racially integrated high school and it had been integrated after WWII when white people began moving into the lower-rent black neighborhood. Here I was allowed to develop my materials that grew into my books. I had the wonderful experience of having students evaluate these historical documents and pictures. My first book, Eyewitness: The Negro in American History, was really shaped by my students. I am still in touch with some of them.

Katz also recognizes the scholars and activists that helped supply him leads, documents, and photographs.

These people included: Ernest Kaiser, one of the librarians at the Schomburg Library, had an encyclopedic knowledge of African American history; Jean Blackwell Hutson, the director of the Schomburg; Dorothy Burnett Porter of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University; and Sara Dunlap Jackson of the National Archives.

These people included: Ernest Kaiser, one of the librarians at the Schomburg Library, had an encyclopedic knowledge of African American history; Jean Blackwell Hutson, the director of the Schomburg; Dorothy Burnett Porter of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University; and Sara Dunlap Jackson of the National Archives.

These unsung black historians and archivists were the ones who were promoting this material. I was guided by the pioneering research of W. E. B. Du Bois, and met and became friends with John Hope Franklin.

I also stumbled on a white researcher, Kenneth Wiggins Porter at the University of Oregon, who was writing on African Americans in the West from the time of Herbert Hoover’s administration.

I met editors Esther Jackson and Jean Carey Bond of Freedomways, a journal of the Black Liberation Movement and began to write articles for them in 1970. By this time Howard Zinn was taking people’s history to the public.

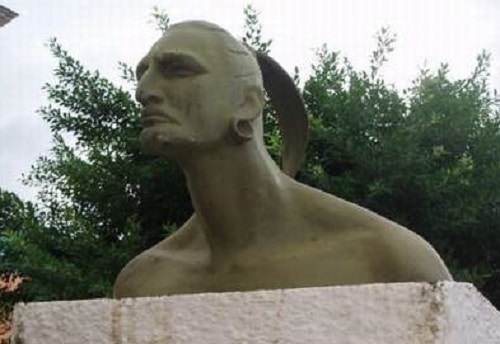

Asked to name his favorite book, he turned to the subject of Black Indians.

Asked to name his favorite book, he turned to the subject of Black Indians.

A number of my books like Eyewitness and The Black West caused quite a stir, but nothing like Black Indians. People called me at night, wrote letters, sent me photos, called in to radio programs to ask questions, people stopped me on the street.

The book has not been reviewed in any major publications, but was sold by local street vendors in the major cities. Yet I was being invited to address the National Alliance of Native Americans and made an honorary member. An Ohio Black Indian organization gave me an award for bringing people of color together. American Indian Studies and African American Studies departments at colleges were asking me to speak, and I was interviewed on African American and American Indian radio and TV programs.

Katz sees the connection between The Lincoln Brigade and The Black Indians, and the crux of his life work, being the way these stories highlight alliances that people have built over time across racial and ethnic lines despite living in a deeply racist society. He believes these examples will inspire students to create the kinds of communities they want to live in. This goal was further realized on July 17, 2014, when the National Congress of Black American Indians was founded at a conference at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., with Katz as their resident historian.

Katz concluded with words of advice for people who are debating whether to become a history teacher in the face of the countless challenges facing the profession.

They should follow their courage and go ahead. I don’t know if I can offer relevant advice since I had to bootleg material into my classroom. Now Howard Zinn’s books are out there and have broken barriers. Zinn proved that this kind of history can’t be ignored. People have to stick to their principles. I have always maintained that the school curriculum has been an important obstacle to progress in public policy. It has misled people about what our history has been and who has made it. We need educator activists to keep doing what they are doing.

Interview of William Loren Katz conducted in the fall of 2014 by Alison Kysia for the Zinn Education Project.

You are the greatest.