One of the most common questions teachers ask at the end of a unit on the Reconstruction era is “Was Reconstruction a success or a failure?” And it’s no accident.

State and school district standards across the country ask students to, in the words of one Texas state standard, “describe and analyze the successes and failures of Reconstruction.” Textbooks and curriculum follow suit. In their “Topic Closer” on Reconstruction, U.S. History Interactive, published by Savvas Learning Company — formerly Pearson K12 Learning, asks students to write on what they have learned about the “successes and failures” of “Reconstruction measures.”

However, the debate about the “successes and failures” of Reconstruction was framed by the racist and discredited Dunning School. This group of historians argued that Reconstruction “failed” due to the faults of Black people. As Dunning School historian William Watson Davis wrote in The Civil War and Reconstruction in Florida, “The attempt to found a commonwealth government upon the votes of an ignorant negro electorate proved a failure. It was an injustice to blacks and whites.” . . .

The Dunning School interpretation of Reconstruction remained the dominant portrayal of the era until the Civil Rights Movement forced a reexamination of Black history in the 1960s. Yet despite decades of new scholarship on Reconstruction, K–12 curriculum is still too often stuck in a framework shaped by the Dunning School. As the Zinn Education Project report on Reconstruction state standards argues:

The “successes and failures” framing often neglects to ask “for whom?” and encourages inaccurate and white supremacist Reconstruction education today. It undercuts the era’s on-the-ground movements, disconnecting the actions of people from the consequences of history. It belies the radical possibilities, unparalleled civil rights progress, and devastating white supremacist terror that are all so characteristic of Reconstruction. It assumes a sense of passivity, often asking students to consider only elites or vague monolithic entities like entire states or bodies of government as primary actors building toward inevitable outcomes. In so doing, this framing separates the genuine achievements of Reconstruction from the coalitions of Black people who made them possible and the racist dismantlers who deliberately rolled them back.

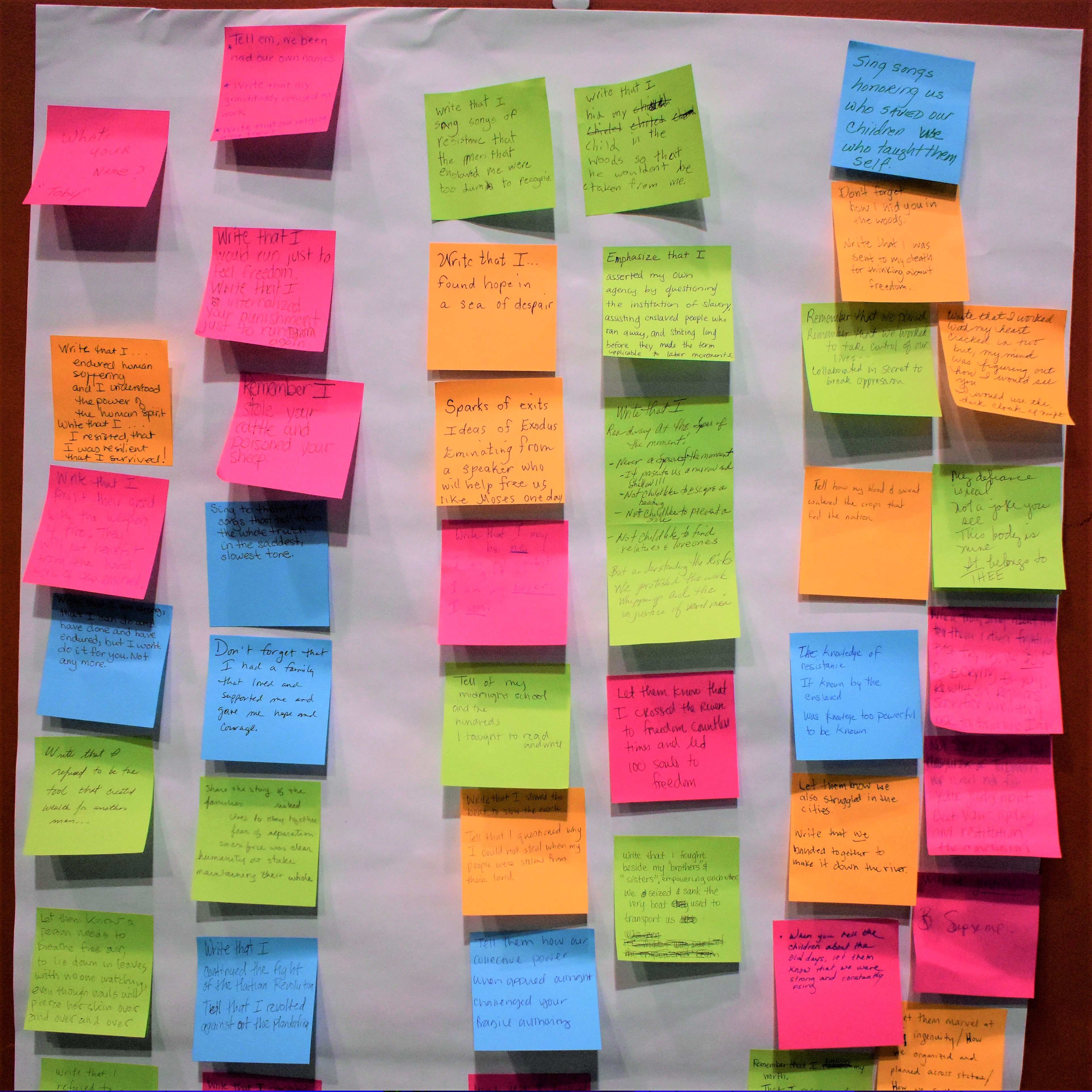

For several years, I’ve been ending my unit on Reconstruction with a better question: “Who — and/or what — Killed Reconstruction?” Most textbook accounts point the finger exclusively at the Ku Klux Klan and white supremacist terrorists who violently attacked Black people and their allies throughout the South. With my Rethinking Schools colleagues Bill Bigelow and Ursula Wolfe-Rocca, I co-wrote a trial role play that encourages students to take a broader view of Reconstruction’s demise looking at the role of the major political parties and their wealthy backers, the racism of poor white people, and the systems of white supremacy and capitalism.

The trial begins from the premise that the death of Reconstruction was a terrible crime with disastrous consequences for the United States and the world.

Continue reading this article with the trial role play lesson at Rethinking Schools.

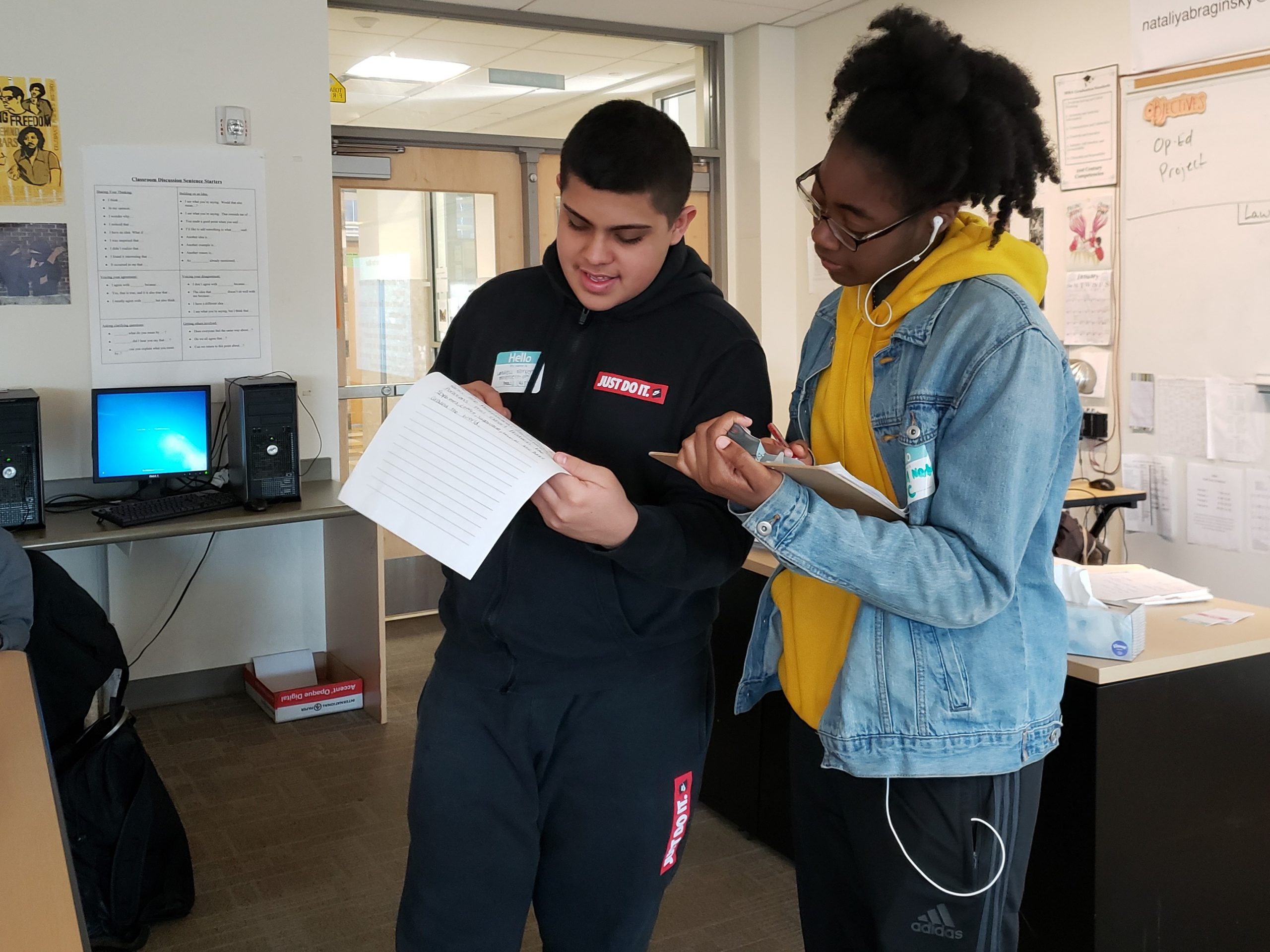

Classroom Stories

It’s not often that you find teenagers volunteering information about what’s happening in history class to their parents, but during family conferences, families wanted to know more about this “trial” that their students had been talking about. A set of twins compared notes across classes on the drive home from school, another student had his mom call her friend who was a DA to help prepare for the big day. It was conversations like these that made me grateful for the Reconstruction trial activity.

I was impressed with our freshmen students tackling such complex topics with confidence — supporting their arguments with evidence and pushing one another to defend their thinking. This activity not only provided an opportunity for students to engage with meaningful questions and information, but it also helped to solidify our learning community and prompted students to write well-crafted essays.

It was so gratifying to see the many directions that students took their writing. Some explored the question “How does one prosecute a system?” Others explored “How are white supremacy and capitalism dependent on one another?” Others explored the ways in which the poor white community was manipulated by those in power. Although, of course, there are ways in which I will adapt this learning for current students, I can’t imagine teaching this unit again without it.

I am always looking for new ways to help my students relate to and understand the past, particularly the nuances and complexities of history. So, when a colleague and I discovered Who Killed Reconstruction? A Trial Role Play, I was really excited to try it with my students. We began by going through a unit on Reconstruction because I wanted to make sure they would be familiar with the basic terms and concepts introduced and have a clear understanding of the timeline. Then, they were each assigned a side and given the opportunity to prepare their opening statements.

To my surprise, I was surrounded not by raised hands and questions, but by furious writing and page turning. My students outdid my expectations for their arguments, and some of the best framed speeches came from students who usually hesitate to raise their hands. Because the packet contained a prepared speech, research materials, and the option to tailor their argument as needed, my students — who often struggle with independent research — were able to work on their own and craft nuanced speeches and appeals. The debate was lively and the jury took a long time to deliberate.

For homework, each student reflected on who they thought ultimately should be blamed for the death of Reconstruction, and I was excited to see the passion my students brought to their arguments. I will definitely be doing this activity again next year with my class!

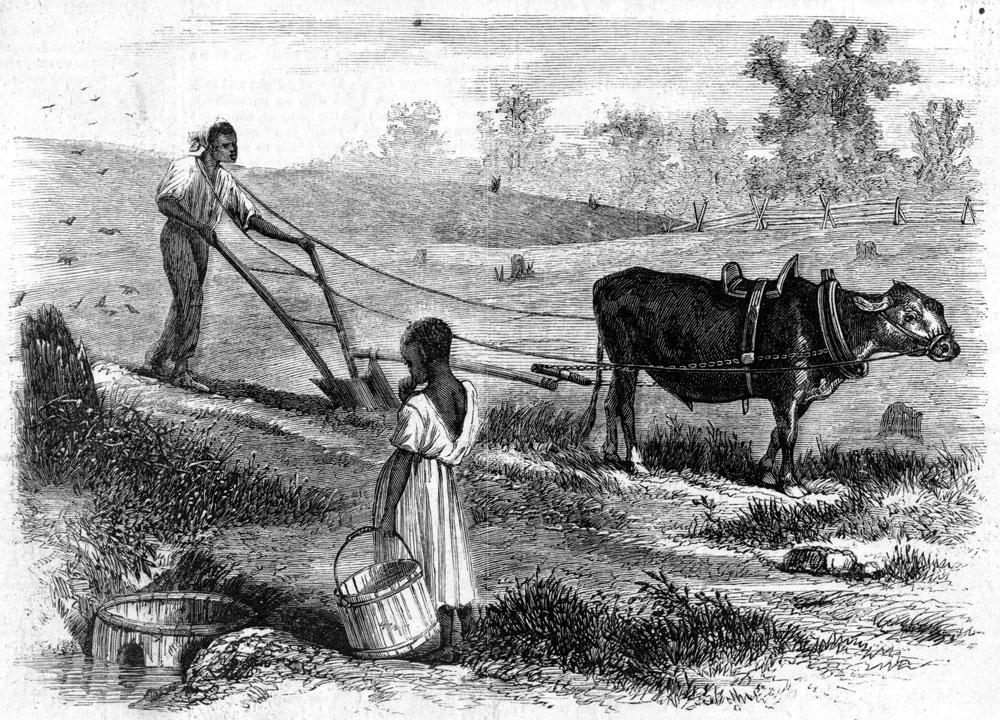

I used two of the Reconstruction role plays in my 10th grade U.S. history class. After discussing their ideas on what “freedom” should entail and sharing four main categories that the freed slaves pursued — family unity, education, political involvement, and land ownership — I had the students participate in Reconstructing the South: A Role Play. Without any knowledge of how Reconstruction turned out, the students effectively reasoned on the need to grant economic independence to the formerly enslaved people and the need for defensive measures against retaliation. Their main struggle was with how to appease white politicians’ fears over reappropriating land in order to get their proposal passed in Congress. The activity pushed the students to grapple with attaining justice within the confines of reality.

The second activity I did at the end of the Reconstruction unit. After discussing the peak of Radical Reconstruction and its decline to the point of being seen as a failure, I had the students complete the Who Killed Reconstruction? A Trial Role Play. Despite saving Capitalism for the end and the student assigned to that topic effectively showing how the previous prosecutors’ arguments also point to Capitalism being the primary guilty party, the jury still placed the largest amount of blame on Racism.

Over the years, I have struggled to find a way to teach Reconstruction in a manner that is meaningful, engaging, and reflective. One of my first attempts included the use of Foner’s massive text on Reconstruction. I’ve also done screenings of Henry Louis Gates’ fantastic documentary series on Reconstruction. But I haven’t had success in getting students interested in understanding how and why Reconstruction failed — until I used the lesson Who Killed Reconstruction?: A Trial Role Play. Not only did my students love the lesson, I was able to implement the lesson with little outside work.

Thank you for making this history approachable! This is just one of many Zinn Education Project lessons I’ve used over the years, and is by far at the top of my list — right up there with the COINTELPRO lesson. I love that I can share my experiences using ZEP lessons with colleagues and know that they will have great outcomes with their students as well.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn